In Spike Lee’s essential 1989 film Do The Right Thing, there’s an omnipresent radio host named Mister Señor Love Daddy (played by an animated Samuel L. Jackson) who narrates and looks down, God-like, upon the scorching Bed-Stuy neighborhood where the story takes place. You’ve probably seen the title recently on the lists of anti-racist movies circulating on the internet in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests sparked by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and so many others, and that’s because Lee’s movie is an immaculate, multi-layered study of race in America that’s just as relevant now as it was in 1989—if not more so.

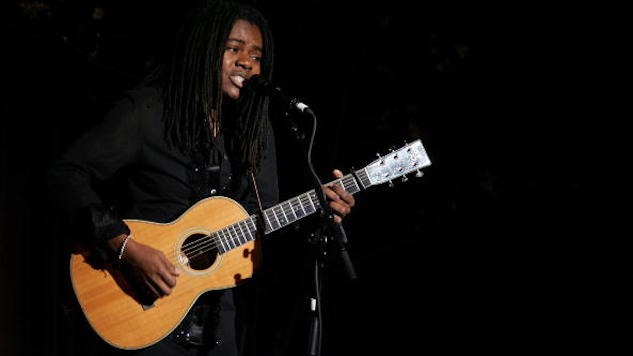

A year before Do The Right Thing hit theaters, earnest folk/pop singer/songwriter Tracy Chapman released her self-titled debut album. There’s a moment in the movie when Jackson’s deejay character pauses to list the dozens of popular Black American artists who dominate the station’s playlists—everyone from Whitney Houston to Ray Charles. The exhaustive list further emphasizes the massive role Black Americans play in our music and culture (one of many themes scattered throughout the film), and Chapman is also among these names. Look to the left of the frame, and you’ll also see a Tracy Chapman poster leaning against the studio wall.

She’s not often talked about as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, but she should be. Tracy Chapman deserves her spot in that radio station roll call alongside Bob Marley, Janet Jackson and everyone else. If you need proof, just listen to her self-titled masterpiece from 1988, which combines the best of folk, pop, rock, jam and country to construct one of the most moving narratives you’ll hear on a solo album from that time period—or any time period. Not only is Tracy Chapman deeply personal, it’s also a startling collection of protest songs and stories of oppression that still hit home today.

“Talkin’ Bout a Revolution” is the record’s first single and opening song and is widely known for its political message. It’s arguably right up there with “What’s Going On,” “The Times They Are A-Changin’” and “Fight The Power” (also the recurring song from Do The Right Thing) as one of the best protest songs ever written. While it’s no less subtle than those three tunes, it is a little softer as Chapman actually “whispers” over acoustic guitar before shouting the “run run run!” of the fiery chorus. It’s straightforward, and therefore, powerful: “Poor people gonna rise up / take what’s theirs.” It’s no wonder Bernie Sanders played it before rallies during his 2016 presidential campaign.

The Grammy-nominated “Fast Car,” the other single from Tracy Chapman, is a masterpiece of narrative and a dynamic study of family. There’s little I can say here that hasn’t already been said about this adult alternative hit (and mainstream, too—it peaked at number six on the Billboard Hot 100), but it’s necessary to re-emphasize this song’s seriousness. “Fast Car” caught a second wind when it was remixed by English house producer Jonas Blue in late 2015, and it reverberated across college campuses, fraternity houses and clubs, landing a new reputation somewhere between cheesy ’80s rehash and soft-rock coffeehouse-snoozefest-turned-drinking-anthem. I was already a fan of Chapman’s original version, and I’ll never forget my shock upon hearing the electronic remix blare over the loudspeakers of one particularly sticky college bar. It sounded so out of place, because “Fast Car” isn’t supposed to be a song you black out to—it’s meant to wake you up. Chapman manages to criticize capitalism and the impossible-to-achieve American dream while also ripping out your heart strings and playing them alongside her guitar, and then somehow leaving you with some hope and peace at the end of it all. She played the song during the broadcast for Nelson Mandela’s 70th Birthday Tribute in June of 1988, and the rest was history. Thankfully, “Fast Car” still remains popular in its original form: Luke Combs and Black Pumas both recently shared covers of the song, and it sounds as timeless as ever.

Elsewhere on the album, “Why?” is one of those all-encompassing socially-conscious songs that would’ve appeared during a Farm Aid set in the ’90s, but that doesn’t mean it (still) doesn’t ring true, especially questions like “Why is a woman still not safe when she’s in her home?” (which sadly recalls the brutal killing of Breonna Taylor at the hands of police) and “Why, when there are so many of us, are there people still alone?” But, like many great protest songs, it’s not entirely desolate. “Why?” urges us to fight for what’s right in the hopes that someday the clouds might part: “Somebody’s gonna have to answer / The time is coming soon / When the blind remove their blinders / And the speechless speak the truth.” Later, on “If Not Now…” that fight becomes more urgent. “If not now, then when?” she pleas. 2020 is proof that sometimes waiting isn’t an option. Convenience is not a factor in fighting for justice and truth.

“Behind the Wall” is a chilling a capella recount of domestic violence in Chapman’s neighborhood which illustrates how much harm police can cause within oppressed communities: They’re threatening at best and deadly at worst. “I’m here to keep the peace,” the officer in her song says, droning on, “Will the crowd disperse? / I think we all could use some sleep.” Tracy Chapman also has its share of tender moments, especially “Baby Can I Hold You,” “For You” and “For My Lover,” a twangy and moving ballad about a forbidden love that works as a metaphor for Chapman’s own sexuality, which she has mostly kept quiet. It may sound like the characteristically frivolous balladry of the day, but heard in the context of Chapman’s own private life, it’s anything but.

From its staying power as a message of the realities of oppression to its many protest songs, Tracy Chapman is important for so many overt reasons. But it also can’t be overstated how notable it was that a Black, queer woman singing about hot-button social issues could be as popular as she became in the late ’80s and early ’90s—if ongoing events are proof of anything, it’s that our society has never been as progressive as we’d like to credit it as being. So Chapman—now, as she has always preferred to be, mostly hidden from the public eye—is an anomaly. We’re blessed to have the music she made against all the odds. Her self-titled debut is, in some unfortunate aspects, still as relevant as it ever was. More than 30 years after its release, we still haven’t fully answered her call to remove the blinders and speak the truth. The least we can do is listen again.

Ellen Johnson is an associate music editor, writer, playlist maker, coffee drinker and pop culture enthusiast at Paste. She occasionally moonlights as a film fan on Letterboxd. You can find her tweeting about all the things on Twitter @ellen_a_johnson.