“A man needs to know his limitations,” Clint Eastwood’s stoic Dirty Harry character once declared. But Old 97’s frontman Rhett Miller doesn’t quite see it the same way. As a novelist, essayist, podcaster, short story writer, standup comic, children’s book author, solo artist, and vocalist/guitarist for his band for nearly three decades, he simply hasn’t found his yet. Or none that he can’t creatively push to the point of breaking.

This time around, on the Dallas quartet’s new aptly-dubbed Twelfth outing, even physical limitations couldn’t hold Miller back. Guitarist Ken Bethea suddenly required emergency spinal cord surgery, he recalls, “So that was a little scary, and that pushed the record back by about a year. And then Philip [Peeples, drummer] had a bad accident—he fell down in a parking lot in just a pre-low-blood sugar moment and wound up in the ICU—he’d smashed his head open, and it was bad, so he missed the first month of the tour for our last album, Graveyard Whistling. So we’ve had some weird stuff happen recently, but we’ve been pretty lucky, knock wood.”

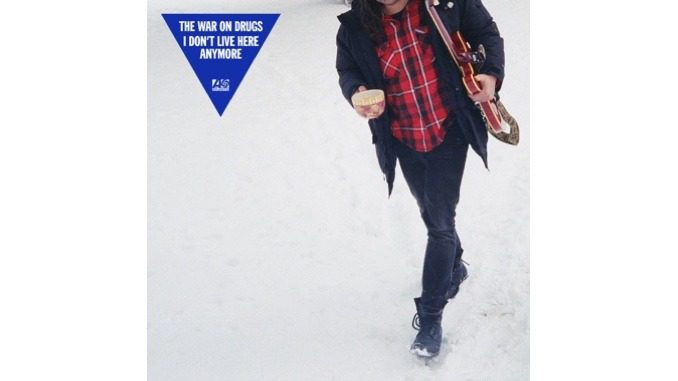

Yet somehow, the composer managed to pen one of the most joyous, bell-chiming collection of subtly snarky anthems in his whole cowpunk-smoky career, completed just before the global coronavirus lockdown this March and featuring a photo of one of Miller’s all-time sports heroes on the cover, former Dallas Cowboys quarterback Roger Staubach. The first galloping single is almost a primer on pop songwriting in itself. “Turn Off the T.V.” charges in on an upbeat rhythm, and the singer’s patented woodsy drawl casually observing that “They’re running a marathon of Kids In the Hall/ Ghost light dancing ’cross the posters on the wall/ Two little Pixies and a side of T rex/ I can tell that we get along well and I wonder what’s next.”

It’s visceral, image-laden poetry that’s even more sleek and streamlined than the man’s earliest wordplay, when he was spinning out witty couplets “What’s so great about the Barrier Reef?/ What’s so fine about art?” And it’s hard to tell which best encompasses the track’s hook—its sing-song chorus of “Turn off the T.V. let’s go back to my room/ I’ve got a window with a helluva view” or Bethea’s booming Duane Eddy lead that sets fire to everything immediately afterward. Miller just keeps getting sharper, shrewder, more adept at his craft, and the 97’s keep getting tighter, through a clanging “The Dropouts,” the intricate “This House Got Ghosts,” a waltzing tribute to a real Dallas institution “The Belmont Hotel,” and bassist/vocalist Murry Hammond’s two typically-chugging contributions, “Happy Hour” and “Why Don’t We Ever Say We’re Sorry.”

“But as a band, we’ve always been pretty lucky,” says Miller, who turns 50 this week. “Pretty smart, even, about being grateful for this thing that we’ve got. We’ve never broken through, we’ve never gotten rich, we’ve never had the kind of thing where we went from being a cult favorite to being a popular band. But I think that’s good. For me, as a writer, it’s kept me hungry. We put together a band of four people that really could get along and care for each other, and we’ve shared the revenue from what we’ve made pretty equally. So we all realize how lucky we are, and that if we don’t fuck it up, we can literally keep doing this until we’re 97 years old.”

Paste: You’re up in New York’s Hudson Valley. How have you and the family been handling lockdown?

Rhett Miller: What can I say? I’m fine. My 16-year-old son Max was testing me a little bit because he’s a teenager, but in a good way. He’ll be very sensitive when I’ll say something that criticizes his driving, and it will hurt his feelings. And yes, he’s driving now—it’s crazy. And he’s already got a 17-year-old girlfriend, too. I think he’s winning the pandemic.

Paste: I wonder how his generation will see 2020 years from now, in retrospect.

Miller: Well, Erica [Iahn, Miller’s wife] and I ran from the Trade Center in New York on 9/11. But that was like a one-day thing. It affected a few months of our lives because we were homeless and we never got our stuff, but that was like a terrifying day with a bunch of bullshit afterwards. But this? This is gonna be like…like the whole second half of his high-school career is gonna be this shit. It’s pretty weird. And my daughter Soleil is quarantined, and she’s going into high school next year. And in a normal world, she’d have a boyfriend, maybe, and do all this social stuff. But there’s just…just nothing. Just her and her phone. But we are in the Hudson Valley, and there’s jus so much crazy shit right here. The Mohawk Mountain is just up the road, like 15 minutes from here, and that’s a famous resort and a glacial lake, and we’re surrounded by swimming pools and cliffs where you can go cliff diving. So this is the perfect place to be during a pandemic, I would think.

Paste: Have you seen any of the guys in the band?

Miller: No. We’ve been doing Zoom calls like everyone else, but we’ll do ’em with our band so we can see everybody’s faces. And we complain about how we miss each other, and we’re bored, and we wanna hang out and get back to work. It’s just weird.

Paste: And you’ve given up drinking for a while now?

Miller: It took me a little while—I’m a slow learner. But really, I miss smoking weed more than drinking. But I found that it really needed to be all or nothing, and the weed feeds into my OCD so hard, I’d find myself cleaning the pipes and the dugout, and de-seeding the this or that, because there’s so much ritual that goes into it that only hours later will I realize that all I’m really doing is upkeeping my paraphernalia too much. And my OCD definitely gets way worse when I’m having a lot of anxiety. There have been times in my life where things have been spiraling out of control, and I’ll find that I’m rearranging the couch pillows 1,000 times, because they’re not perfect but they have to be perfect.They have to be perfect, you know?

Paste: What lessons have you learned from this surreal COVID-19 situation?

Miller: It’s funny. My daughter’s 14, and Ashe’s told me that I’m not allowed to make the joke of saying “I’m stupid,” because I say it all the time if something goes wrong. She said, “You have to stop saying that,” and I didn’t even realize that I was doing it. But I’ve always dealt with a lot of self-destruction, whether it was starting smoking cigarettes at when I was five years old, or the suicide attempt at 14, or the other stuff that came in later in life. I’m really tough on myself, and that can be physical, mental or artistically. I really do beat myself up. But I feel like that with all the work I’ve done in the past decade, I’ve come a long way. Now I feel like I can recognize when I’m being unkind to myself, and I can recognize the talents that I have. And I really feel like with this record, this is the first time where it all came together artistically. These songs are all songs that I wrote myself—there are no co-writes. There are two songs by Murry, but my songs are all mine. And I can answer for these songs, because they emanated from me, and they describe things that I have experienced, things that I’m examining internally or about the world around me. So I feel like I’ve come out the other side of something where I was writing with friends, but I don’t have to write with them anymore in order to finish a song. I can do this myself now. So these songs ended up feeling more personal, more singularly voiced.

Paste: And you actually got to reference Kids In the Hall.

Miller: And originally that song was called “Kids In the Hall Marathon,” and that was the chorus. But I turned it into a verse, and kinda made it a different thing. But I love the Kids In the Hall reference and the Pixies reference, because in the ’90s, when I was young and poor, I was obsessed with Kids In the Hall, and I was obsessed with The Pixies. And now, because of my job and what I do, I’ve gotten to be friends with a number of Kids in the Hall guys and The Pixies, as well. So it’s kinda sweet—I referenced both of ’em in the songs, and I sent out early versions of the song to Dave Foley and Joey Santiago and Charles. Bruce is the only Kid I haven’t met yet. But there’s a comedy connection there, for sure, because I wrote the song “This House Got Ghosts” in San Francisco during one of those annual Sketchfest events that I do every January.

Paste: How did you first get involved with that comedy festival?

Miller: Janet Varney is a friend of mine from Los Angeles, and she is one of the founders and coordinators of Sketchfest. And she invited me, and I think my first one was in 2013. And it’s been so great—I think I missed one year, and I regretted it all year long. It’s been my favorite thing. And I appeared with her recently—we both got invited as celebrity guests for this Dungeons and Dragons thing, and we did a skit together.

Paste: Your wit was already rapier-sharp. How has Sketchfest affected your art?

Miller: Just getting to be around those funny people, and getting to do stuff with them, getting to be a part of improv stuff, getting to get up onstage with these people who think so quickly, I’ve learned that the thing that makes comedy successful is the unexpected. Like, you take a trope, you turn it on its head, and it’s the surprise that makes you laugh. And you’re gasping, going, “I did not see that coming!” And I think I try to do that, although I don’t know how calculated I get about it. And if anything feels too predictable, I try to flip it on its head and go in a different direction. But sometimes it’s good to just let it be what the person expects. Sometimes a cliche can really land and do some of the work, but only if you’re letting it do the work on multiple levels. If a cliche is just being a cliche, the nobody’s gaining anything from it.

Paste: What comics have taught you the most?

Miller: I really loved working with Paul Tompkins and Connie Newsom, these improv actors who can just take an idea and create a story from nothing, just pulling things out of thin air. It just blows me away how they’re able to do that. And I’ve gotten to do some things where I’ll stand onstage with them and sing part of a song, and that becomes part of their improv. So I’m not totally doing improv with them, but even just to be onstage with them, the feeling of exhilaration of having to create entertainment out of nothing, just from whole cloth, is just so beautiful. It’s like an immediate embodiment of what all artists are doing—taking nothing and making it something. But to do it in front of people in real time, with all the pressure of failure on you at any moment? It’s just so brave and so admirable.

Paste: Is there one hilarious improv moment you’re particularly proud of?

Miller: I was on that NPR show “Wit” one time as the musical guest—it’s essentially a comedy show where they do sketches. And the comedy guest was Weird Al Yankovic, and there was one game where you had to make up a song out of an audience suggestion. But Weird Al couldn’t do it, because he said, “If I make up a song, then that becomes part of my catalog, and I can’t do that, I can’t give my material away.” And I totally understood. But then I had to stand next to Weird Al Yankovic and make up a comedy song, and I made up a song about bananas. And that went over quite well, actually. And that was also right about the time I was starting to write the kids’ poems, so I wound up learning a lot about improv and comedy, and it ended up informing No More Poems, the children’s book I put out last year.

Paste: Your own take on the Edward Gorey mythos?

Miller: I love him. But that was the problem with my book—a group of moms in the Midwest started a lynch mob on Facebook because one of my poems was about sibling rivalry, and the dad is begging the older sister not to murder her younger brother because he’s annoying. So he lists off the different ways that she can murder him, like, ‘If you take a pillow and you smother brother’s head/ I’ve got a strong suspicion that he just might wake up dead.’ That kind of stuff. But these mothers went crazy, so for a week in the Midwest, there were all these nightly news broadcasts carrying a story about ‘Children’s author encourages siblings to murder each other! News at 11:00!’ It was a fucking disaster. They torpedoed my Amazon review and got me pulled out of Costco, and that sucked. It actually sucked. But it went away eventually, and I got nominated for a bunch of end-of-the-year Library Association Awards, because clearly my book was not offensive or dangerous, like they were saying. And they bought a new book from me called Baby’s Changing Station, and the illustrator is working on it right now. I’ve really enjoyed writing the kids’ books and visiting schools and stuff, but the hardest thing is remembering not to cuss all the time.

Paste: And there actually was/is a Belmont Hotel in Dallas?

Miller: In a lot of the songs on this album, I’m remembering the earliest days of the band, and how much fun it was to be broke and living in squalor, just driving ourselves around in a shitty van, sleeping on hardwood floors. There’s a line In one song that goes, “I drove a Dodge to a dead-end town/ The night they drove old Dixie down/ I was dishing out pearls to the local swine.” How I miss the local swine! But yeah, the Belmont is a hotel in the Oak Cliff neighborhood of Dallas, which was really swanky in the ’50s. And then it fell into disrepair, and for the Old 97’s first photo shoot, we went to the overgrown central court of the Belmont Hotel and took a bunch of pictures of us in its abandoned, overgrown-with-weeds phone booth in the middle of this decrepit, falling-down hotel. And a few years ago, developers bought it and brought it back to even better than its former glory, and now they love rock and roll people there and they give me a good rate, so I go stay there. And as I was thinking about all the incarnations of this hotel and the lives it had led, and it turned into a metaphor for a marriage—or even a band—that survived through the years: “Our love is like the old Belmont hotel/ It was in ruins now it’s doing quite well.” It’s a really sweet song. And any time I’m writing a song, and as I’m writing it, I begin to cry actual tears, then I think, “Okay—I think I’m on the right track here!”