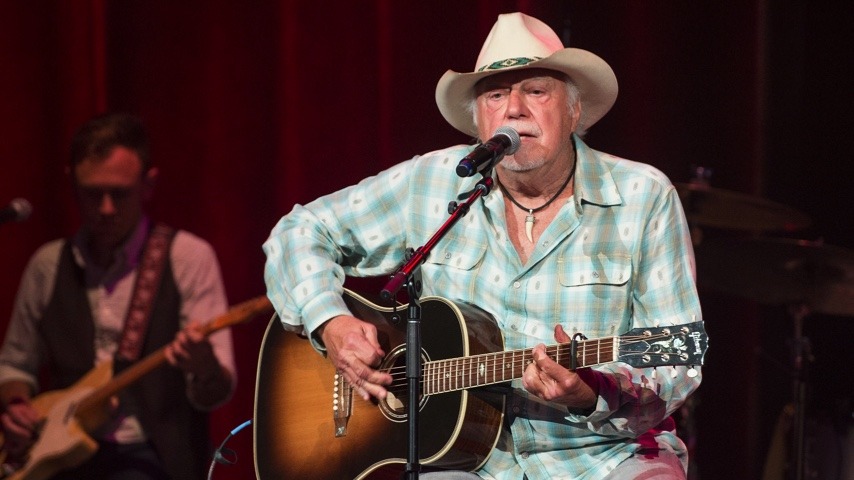

It’s hard to get a handle on Jerry Jeff Walker, who lost his multi-year battle with throat cancer Friday at age 78. He wrote one of the most enduring songs of the 1960s, “Mr. Bojangles,” but he probably had a bigger impact by singing other people’s songs. By doing so, he was a crucial catalyst in launching the Texas Cosmic Cowboy movement. And yet he was born and raised in upstate New York. Hell, his name wasn’t even Jerry Jeff Walker.

He was born Ronald Clyde Crosby on March 16, 1942, in Oneonta, N.Y. He joined the National Guard and went AWOL under the name of Jerry Ferris, thanks to the borrowed ID of a fellow guardsman. He hitchhiked around the country and wound up in Louisiana.

“The folk music boom of the Fifties and Sixties barely touched New Orleans,” Chris Smither told me in 2014. “The Quorum Club on Esplanade had folk acts, and I used to go down there to hang out. This guy Jerry Ferris played there and I thought he was pretty good. Many years later I opened for him when he was calling himself Jerry Jeff Walker. But it was a fringe thing in New Orleans; it has always been a horn and keyboard town.”

Back in Greenwich Village, Ferris renamed himself Jerry Walker after Harlem jazz pianist Kirby Walker. He wasn’t making much headway as one of a thousand guitar-strumming, singer-songwriter folkies that had popped up like mushrooms in the wake of Bob Dylan. So he joined a psychedelic-rock band called Circus Maximus for two albums, before drifting back to the folk scene in the Village. David Bromberg, Emmylou Harris, John Hartford, Bryan Bowers, Peter Tork, Carly Simon, James Taylor, and Robin & Linda Williams were all part of a loose-knit group that did the “basket houses,” where you played half-hour sets for the tips as you passed a basket around.

“We were dreadful poor,” Bromberg told me in 2006, “because you don’t make much money passing a basket around…. But the poorer people are, the more they share. At four in the morning after the bars had closed, we’d go to the Hip Bagel to eat or to someone’s apartment to share a bottle and our newest songs. You’d play, and if someone liked the way you played, they’d say, ‘Let’s get together later….’ The first night I met Jerry Jeff at a party at Donnie Brooks’ apartment, he played ‘Mr. Bojangles.’ How can you beat that?”

Bromberg called up Bob Fass, who had a midnight-to-dawn show on WBAI-FM, and told him he’d found this great songwriter and wanted to bring him to the studio. Bromberg had to drag the reluctant Walker to the radio station, but once the singer was there, he recorded several different versions of “Mr. Bojangles” for Fass, who played all the versions every night on his show. Before long, every folk fan in New York wanted to buy a copy of the song and every record company wanted to release it.

Every record company, that is, but Vanguard, which held Walker’s contract. By the time Walker had gained his temporary release from Vanguard, had signed with Atco, and had flown down to Muscle Shoals, Ala., to cut a new version of the song with Bromberg and producer Tom Dowd, a rival version of the song by New Jersey piano player Bobby Cole had emerged. The two versions battled it out, and the result was two small hits rather than the big hit Walker deserved. The song wouldn’t receive its due until the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band released its top-10 hit single version in 1971.

“Mr. Bojangles” became the title track of Walker’s first solo album in 1968. It was very much a Dylanesque folk album, as was the follow-up, Vanguard’s Driftin’ Way of Life in 1969. But Walker was unable to expand the New York buzz around his breakthrough song. He was suffering the same problem as his fellow New York folkies. Everyone was struggling with the fact that folk music’s commercial moment had passed as soon as Dylan went electric.

How could you find an audience for acoustic folk when you were competing against the memory of the brilliant folk music Dylan and his friends had made in the early ’60s and the example of the sonically powerful folk-rock they were making now? In a psychedelic era, how could you make listeners care about a strummed acoustic guitar and a conversational story? James Taylor would solve this problem by marrying his folk music to the Brill Building pop of his new friend Carole King. Harris would solve it by joining forces with country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons in L.A. Walker would solve it by moving to Austin and adding a middle name.

Austin was the only oasis for bohemia between New Orleans and Santa Fe. As home to the University of Texas and the state government, it had enough teachers, students, bureaucrats and white-collar workers to support the bookstores, coffeehouses, bars and non-profit groups that are the breeding ground for bohemia. And in 1972 that meant hippie culture, a drug-lubricated willingness to try new music, new films, new literature, new clothes, new relationships, new politics. But in the sun-baked environs of Texas, those experiments assumed very different shapes than they did in L.A., Nashville or New York.

In 1972, Austin was still a sleepy Southern capital. The surrounding hills were still full of cattle and rednecks. In town, zoning barely existed; rents were cheap, and the delicious Mexican and barbecue meals were even cheaper. But a year earlier the Texas legislature had changed the state’s blue laws to allow liquor sold by the drink. The college bars along Sixth Street started booking live music, and so did many of the restaurants and halls along the Colorado River.

The gigs didn’t pay much, but musicians could play and develop their sound as they found an audience. Before long, not just singer-songwriters from New York but also country crooners from Nashville, blues guitarists from Dallas, folkies from Houston, rockabilly singers from Lubbock, and Tex-Mex bands from San Antonio were all flocking to Austin. Moreover, they were playing with one another and trading influences back and forth.

It was in Austin that Walker made the same discovery that would change the careers of dozens of musicians. If you took Dylanesque folk songs and played them with a honky-tonk band, they changed in crucial ways. The two-step rhythms and twangy solos shifted the emphasis from intellectual rigor to working-class pleasures. You could still have literary lyrics, but your subject matter was less likely to address social injustice and personal alienation and more likely to concern drinking, romance, and home.

This didn’t make the songs better or worse, but it sure made them different. For Dylan himself, the venture into country-rock proved a brief detour, for his art was better suited for the confrontational qualities of folk-rock. But for artists such as Walker and Harris, whose art was more visceral rather than analytical, country-rock became a career path.

“Our little joke among ourselves,” Walker told ountry Music Magazine in 1994, “was to say we played country music; we just didn’t know which country it was. But the fact is, I think it’s country music because the subject matter of what you’re talking about is rural. Willie [Nelson] didn’t have a fiddle; Willie didn’t have a steel. But nobody’d say Willie wasn’t country.”

The transformation was especially dramatic in Walker’s case, for he went from writing poignant story songs such as “Mr. Bojangles” and “Drifting Kind of Life” to such advertisements for Texas hedonism as “Hill Country Rain” and “Hairy Ass Hillbillies.” In the process, his music developed a swagger that was helped rather than diminished by the rough edges left in the arrangements.

The vocals hinted that the world was best viewed as a giant joke, and the instruments played as if they were still learning the song. This created a sonic template for dozens of similar recordings (by Michael Martin Murphey, Willis Alan Ramsey, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Billy Joe Shaver, and even a few singers with less than three names) that would be labeled the “Texas Cosmic Cowboy” movement.

“I wanted musicians who listened to jazz and blues, some rock and roll, some country, guys with the background to follow me wherever my impulses led,” Walkers says in his autobiography. “I was leaning toward a freewheeling, open approach, the sounds born at some late-night party where everybody’s playing and trying new things, and carrying it over to the next day’s rehearsal. This happened constantly in Austin. You’d play all night with different people, trying out new stuff, listening to other people’s new stuff, new ideas begetting more new ideas. You’d greet the dawn with a guitar in your hand and some new songs or licks in your head.”

Within a few months of hooking up with Austin’s country-flavored musicians, Walker had enough new songs for an album. He went into a studio that didn’t even have a mixing board with a bunch of local musicians who had never recorded before and cut directly to tape as if it were just one more picking party near the U.T. campus. Though he later had to clean up the tapes in New York, he had captured a loosey-goosey spontaneity in his mix of folkie lyrics, blues-rock rhythms and country vocals and solos.

Walker wrote 10 of the dozen songs on Jerry Jeff Walker, but the other two came from Guy Clark: “That Old Time Feeling” and a tune Clark had titled “Pack Up All the Dishes.” But as Walker was mixing the track, all the musicians and engineers kept referring to it as that “L.A. Freeway” song. Finally the singer called the composer and asked if he could re-title it.

If the verses had the conversational tone of Walker’s folkie past—though his acoustic guitar picking is bolstered by organ and drums—the chorus is the kind of rousing sing-along more suited for a sawdust saloon than a campfire or picket line. As the pedal-steel guitar comes swooping in along with a cranked up electric guitar and haphazard harmony vocals, Walker belts out, “If I can just get off of this L.A. Freeway without getting killed or caught, I’ll be down the road in a cloud of smoke.” And on the instrumental coda, the female gospel singers, wailing harmonica and soloing guitar suggest what that trip down the highway might feel like.

“L.A. Freeway” was the first single off Walker’s first Decca/MCA album and though it didn’t chart, it stirred up quite a bit of interest on the underground FM stations of the day. It was a milestone track, for it alerted country-rock fans around the nation that Texas had come up with an original twist on the country-rock model. It transformed Cosmic Cowboy Music from a local scene into a national phenomenon. It established Walker as a cult figure and made his more devoted fans intrigued about this unrecorded songwriter named Guy Clark.

And soon Walker was doing the same for other Texas songwriters: Rodney Crowell, the Flatlanders’ Butch Hancock, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Billy Joe Shaver, Gary P. Dunn, and Lee Clayton. Walker had set out to become the next Bob Dylan, but he had turned into the next Emmylou Harris, an interpretive singer whose ability to spot obscure songwriting gems and bring them to a broader public with his charismatic vocals. If Harris did that with songbird purity, Walker did it with well-lubricated party spirit. But each in their own way sparked a major branch of alternative country music.

It’s often said that Walker never had a hit record under his own name. That’s true when it comes to singles, but between 1975 and 1978 he put four albums in the top-25 of Billboard’s country charts. That’s pretty damn impressive. By 1980, however, Walker had lost his mojo. The partying-cowboy schtick had grown thin; his own songwriting had grown repetitive, and the songwriters he’d relied on had careers of their own to take care of.

Walker is sometimes called the “Jimmy Buffett of Texas,” even though Walker released his first Texas album, Jerry Jeff Walker, in 1972, a year before Buffett released his first Florida album, A White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean. The two men had been friends in New Orleans, even wrote the song “Railroad Lady” together. Both built large followings in the ’70s with a beguiling mix of the sensitive and the rowdy. But once the sensitivity became maudlin and the rowdiness self-indulgent, the charm wore off for both of them.