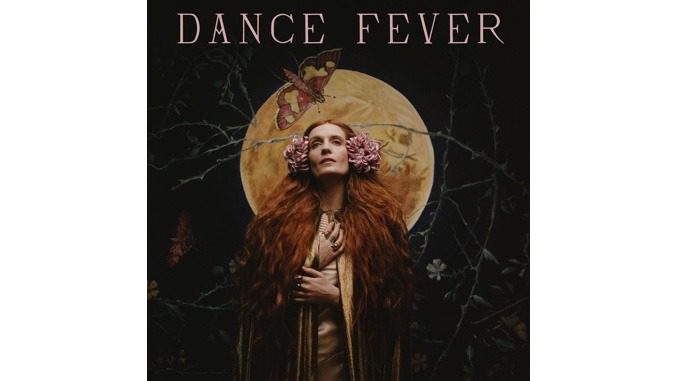

The music of Florence The Machine is consistently singular. The band, led by Florence Welch, have been performing bewitching baroque pop since the late aughts. While their music has become higher in fidelity as their star has risen, they’ve never abandoned their sweeping gothic ambitions. Though they have their occasional moments of stirring quiet, they’re a group best suited to huge, uproarious songs. Welch is a charismatic performer, often possessed by the power of her own music, and is prone to leaping and bounding around the stage, sometimes running through a theater’s aisles. While writing the songs that would, years later, become Dance Fever, the band’s fifth album, Welch read about choreomania, the Middle Ages concept of being so lost in euphoria that one dances themself to death—an idea that would naturally fascinate someone so morbidly devoted to performance. These songs would have to reflect this compulsion in their sound and structure, building them to feel at home onstage. After enlisting pop hitmaker Jack Antonoff, the pandemic began just a week into recording sessions, forcing Welch back to both London and square one. While unable to meet in person, she worked remotely with Antonoff and Glass Animals’ Dave Bayley. The resulting songs are some of the most captivating Florence The Machine have made in years, and exist as a hellish rebuke against stillness.

The opener, “King” is the rare moment when Welch’s sights are set on the stifling nature of gender expectations. Blessed with a pleasant, trotting drum beat, she sounds totally in control as she performs her trademark vocal acrobatics. The lyrics tell the story of Welch eschewing the traditional roles forecasted for her, instead forging her own path. As the song nears its end, Welch cries out, the drums hit even harder, and we’re reminded once again just how much this band can do in moments of all-consuming chaos. The amount of anger swirling beneath the surface of “King” gets drawn out further on the stellar “Girls Against God,” a song that Welch calls “old testament style fury” at the thought of not being able to perform again; it is a glorious moment of misty-eyed vulnerability from a band so often dressed up in fairytales. “Oh, it’s good to be alive / Crying into cereal at midnight / And if they ever let me out / I’m gonna really let it out,” she sings on its refrain; it’s as important to show the phase of confinement as it is to show the cry of freedom.

Though Dance Fever promises to be an explosive record, bolder than the band have been before, it is frequently subdued. Moments of palpable catharsis sit amidst a collection of ballads, mid-tempo cuts and curious interludes scattered throughout the tracklist. One such track, the wandering piano ballad “The Bomb,” finds Welch doing her best Stevie Nicks as she attempts to write her own “Landslide.” She sings of fatalistic love and giving everything she has to a partner who is happy to take it, while giving nothing back—“I don’t love you, I just love the bomb.” The sonorous “Back in Town” paints a similarly dark portrait, but it contains a spark of hope. Its story plays out like the somber reprise to the bombast of the Lungs track “Hurricane Drunk.” Our devastated, downtrodden narrator returns wiser and more cynical. Meanwhile, “Heaven Is Here” may fall short of the two-minute mark, but feels fully realized: Laden with chattering percussion, it’s more an unnerving incantation than a song, and plays on the sort of folk horror themes woven throughout Welch’s songwriting—“And every song I wrote / Became an escape rope / Tied around my neck / To pull me up to heaven.” However, the other quick moments, “Prayer Factory” and “Restraint,” do not meet the same high-water mark. The former teases a gloomy, dramatic rock tune, only to burn out just as quickly as it started. The latter lasts just 48 seconds, with Welch’s typically angelic voice twisted and mangled into a desperate, raspy croak, before the song is swallowed up in a gasp. These theatrics are unfortunately short-lived.

Despite enlisting one of pop’s biggest producers and a member of a band that seems to live on festival posters, Dance Fever is home to some of Florence + The Machine’s most interesting rock songs. While nothing can touch the punk-rock snarl of “Kiss With a Fist,” there’s a surprising amount of Springsteen influence present. A standout of the record, Welch’s delivery on “Free” recalls The Boss, with its production and instrumentation practically dropping him on the Coachella stage. This half-spoken cadence returns on what is functionally the album’s thematic core, “Choreomania.” A spoken-word intro and dated-sounding keys begin the song with an ill omen. Fear sets in that this is about to be a Sia-quality pop song. Fortunately, this is a song that shifts and changes like nothing the group have done before. At its apex, Welch repeats its chorus—“Something’s coming / So out of breath / I just kept spinning / And I danced myself to death”—and her performance lets it spin out of control, before quickly cutting off, a body dropping to the floor. It is here and on the glitzy “My Love” that the vision of the record is most clearly represented. While not quite at the level of Calvin Harris’ “Spectrum” remix, the electronic influence of Bayley is immediately noticeable after an angelic choir gives way to a pulsing club beat. Welch once teased she might one day make a dance-pop record—perhaps this is a sign that the dream isn’t dead.

While Dance Fever only sometimes delivers on its larger-than-life ideas, the resulting 14 songs are some of the most diverse and memorable the band have released in quite some time. They hold on to their concept loosely, keeping it within reach, but never losing themselves in the overthinking that typically plagues such projects. Fans of this band’s flair for melodrama and of Florence Welch as a captivating figure will be pleased by this offering. When a band have been so focused on their brand for as long as Florence + The Machine have, it’s easy for them to box themselves in, muting their power; instead, Dance Fever is the sound of a band finding an escape route, rediscovering what makes them special.

Eric Bennett is a music critic with bylines at Post-Trash, The Grey Estates and The Alternative. They are also a co-host of Endless Scroll, a weekly podcast covering the intersection of music and internet culture. You can follow them on Twitter at @violet_by_hole.