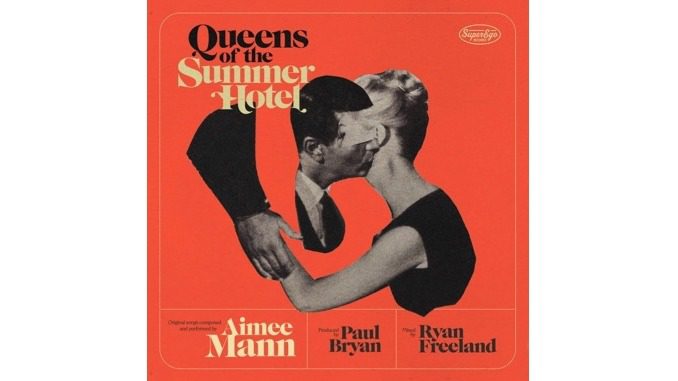

Any pop musician who’s tried writing a stage musical will tell you the process tends to be prolonged. Turns out a global health crisis doesn’t make things go any faster. Aimee Mann had been writing songs over the past few years for a stage adaptation of Girl, Interrupted, a memoir by Susanna Kaysen about her stay in a psychiatric hospital in the late ’60s, when the pandemic put the project on hold. Rather than shelve what she had been working on, Mann compiled the songs into Queens of the Summer Hotel, her 10th studio album.

She’s well-suited to the subject matter. Mann has long been intrigued by trying to unravel the knots of impulses and seeming contradictions that make up our psyches. She has spent a big chunk of her solo career exploring themes of mental illness—the phrase was even the title of her Grammy-winning 2017 album—and she’s been frank about her own mental health struggles. “It’s both sort of fascinating and gratifying to realize that people’s behavior has an internal logic, like classifying it as symptoms more than personality traits,” she once said in an interview.

There’s plenty to work with here: Mann examines mental health from different angles, on tracks by turns mordant, biting, distressing and deeply sad. Queens of the Summer Hotel is not an upbeat album, to say the least. Yet the songs are tightly constructed, full of smart wordplay, vivid imagery and characters who are largely sympathetic. On opener “You Fall,” over a brisk piano figure augmented with strings, Mann narrates while one of those characters watches herself having a breakdown, as if observing from the outside, her façade crumbling with each sip of her drink. Later, on “At the Frick Museum,” Mann sings in the voice of someone who is remembering a college trip to New York that included seeing Vermeer’s painting Girl Interrupted at Her Music, which yielded the title of Kaysen’s memoir. The jaunty “Give Me Fifteen” finds a cocky doctor boasting of his ability to diagnose patients in just a quarter-hour, mostly by not really trying to understand their situations.

Sometimes Mann is direct and unflinching: She spells out a grim bottom line on “Suicide Is Murder,” a downhearted and deceptively catchy tune. Sighing strings and wordless vocal harmonies flesh out a spare piano part as she declares that killing oneself is a “premeditated, rehearsed tragedy” that permanently disfigures the devastated loved ones left behind. She’s more circumspect on other songs: Mann sings the heartbreaking “Home by Now” from the perspective of a girl who describes the nice apartment she shares with her discomfitingly attentive daddy, who “says I’m awfully good at secrets,” without seeming to question whether that’s such a good thing.

Most of the songs on Queens of the Summer Hotel don’t have the punchy pop heft that characterizes much of Mann’s catalog. As hook-laden as they are, these numbers more often sound like she was writing them for a musical—which, of course, she was. Most of the musical arrangements here are piano-based, with rich orchestrations from Mann’s longtime collaborator Paul Bryan. The instrumentation helps frame the songs: an innocent, lullaby-like piano part on “Home by Now” contrasts with the harrowing implication of the lyrics, while swells of strings sweep around a lilting fingerpicked acoustic guitar part on “Burn It Out,” lending a sense of tumult beneath a placid surface as the narrator longs to burn away secrets she considers shameful.

Kaysen’s book wasn’t structured around a linear plot, and neither is Queens of the Summer Hotel. The result is songs that often feel anthologized, and without interstitial dialog or music it’s not always clear how the stories they tell relate to one another as part of the narrative arc that will, presumably, someday underpin a stage show. All the same, Mann has created compelling, complex sketches of characters who are more than the cliches of mental illness that so often appear in popular culture. It will be fascinating to see how she brings it all together.

Eric R. Danton has been contributing to Paste since 2013, and writing about music and pop culture for longer than he cares to admit. Follow him on Twitter or visit his website.