St. Vincent’s self-titled 2014 album seemed a sea change: On the cover, and in live performances, Annie Clark outwardly embraced the alien, with a cult-leader stare, fried white hair and calculated, choreographed movement. I wrote about that album’s rejection of gender binary and its declaration of self-ownership, which set the stage for a strangeness we had not seen from St. Vincent. 2017’s dramatic electro-pop album MASSEDUCTION followed in that theme, albeit with more—sorry—seduction.

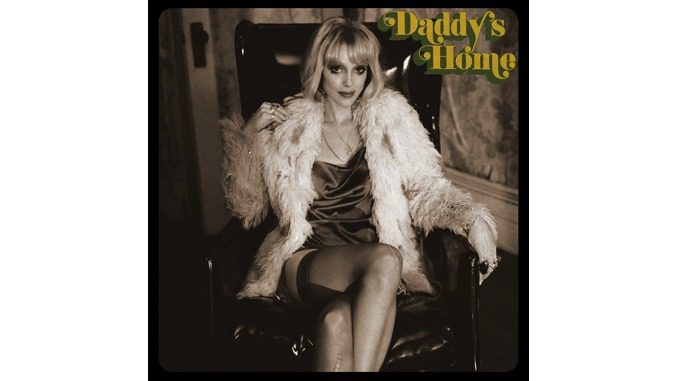

But Daddy’s Home offered a new premise: an album based around Annie Clark’s relationship with her father, thick with ‘70s licks and thrums. However, the story behind the album (her father’s incarceration) and her tendency toward indulgence (like the aimless “Humming” interludes) bog an otherwise masterful, diverse album down with unnecessary weight.

Clark is an endlessly self-assured performer; her bite and control compel even when the album goes astray. Whether she’s wearing a stiletto or cleat, she’ll stomp hard. Daddy’s Home is no exception. The album flickers between dreamy jams and ‘70s ballads, between horn-filled funk and soul backup singers. The first track, “Pay Your Way in Pain,” funky and choral, shows what the album could have been: trippy, upbeat. It’s also a stage-setter, a pseudo-apocalyptic, neurotic prologue (“The show is only gettin’ started / The road is feelin’ like a pothole”).

Most of the following songs are far more tame, a mix of bluesy ballads and psychedelic, sprawling crooners. What makes the album fun is Clark’s tendency toward the theatrical—sharp breath, shouts, radio distortion, horns.

That’s clearest on “Down,” with its short, harsh lines and brash opener: “You hit me one time / Imagine my surprise / When you hit me two times / You got yourself a fight.” It’s dark, sensual, and moody, threaded with blunt gasps—a snarl of a song. “I’ll take you down” is a clear threat, and she only ramps up: “Go get your own shit / Get off of my tit / Go face your demons … Go blame your daddy / Just get far away from me.” Like “Pay Your Way in Pain” and “Down and Out Downtown,” there’s a MASSEDUCTION-era sensuality that makes the anger especially gritty.

But when Clark’s not being as direct, she turns to self-aware snark and sarcasm. It’s a tendency made all the more potent by the album’s bleary, gauzy affect.

“The Laughing Man,” for example, is firmly tongue-in-cheek. The refrain is the hokey “If life’s a joke / I’m dying laughing,” and the song starts with a false 911 call, where she reports: “911 … I’m in love.” Musically, it’s the firmest link between Daddy’s Home and Clark’s Strange Mercy era: It tinkles, meanders, and centers on voice and story. And like all the best St. Vincent songs, it handles cliches with a smirk.

On “Daddy’s Home,” Clark’s similarly smug, “signing autographs” in the visitation room. She sings: “You did some time / Well, I did some time too,” and walks up the latter line’s vocal playfully, alongside a horn riff. Her smugness turns, though, to petulance and self-aware reluctance on “My Baby Wants a Baby,” a funk-pop track where she worries over how her childhood might impact her motherhood, and how motherhood could hinder her personhood (e.g., “I want to play guitar all day”). Then there’s the fear of passing on problems without solution: “What in the world would my baby say? ‘I got your eyes and your mistakes.’” It’s not just the potential limitation of individuality: What if she repeats her parents’ own missteps, or watches another version of herself suffer?

In this way, the snark opens up to sincerity: “The Melting of the Sun” is an ode to female performers who faced addiction, tragedy and hostility. “Live in the Dream” is sprawling, synthy, and “Strawberry Fields Forever”-hazy, both a promise to protect and an admission of fallibility (“I’ll keep you in my arms” segues into “But I can’t live in the dream / The dream lives in me”). “…At the Holiday Party” peeks sympathetically at—and relates to—an unhappy life: “Your Gucci purse a pharmacy / Pretend to want these things / So no one sees you not getting / Not getting what you need.” She relates: “You can’t hide from me.”

But despite Clark’s well-constructed, immersive songs, the album lacks an arc, bouncing between commentary, sticky jams and funk rock, which adds slog to the 44-minute runtime. Too occupied with possibilities, it finds inspiration in motherhood and Candy Darling and crumbling power structures and incarceration and abstract grit.

All Clark seems to want is ownership over her story—that’s what we saw with St. Vincent, and that’s what she told Entertainment Weekly, to some degree, about her father’s story becoming enmeshed with her own years ago: “I’m the daddy now.” But with such a command of genre and talent for composition, her “story” seems somewhat irrelevant. It’s a shame to hamper the music with it.

Daddy’s Home brings us a far moodier, expansive work than predecessor MASSEDUCTION; it begs us to sit and listen, calling back to the slow-burn complexity of Strange Mercy. Whether this funk-soul hybrid persists in her next work is immaterial; it’s the array of tenderness, cruelty and authority that will bring us back again.

Caitlin Wolper is a journalist and poet whose work examines culture, music, identity and more. She’s written articles for the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Vulture and others, and her poetry chapbook, Ordering Coffee in Tel Aviv, is out now via Finishing Line Press. She gets very excited about music, line breaks, and memes on Twitter at @CaitlinWolper.