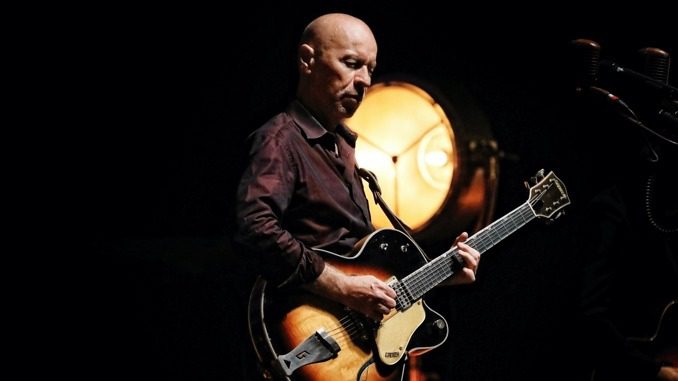

Sorry for the slight delay, apologizes British composer/conceptualist Matt Johnson. But by all accounts, the ephemeral 2018 reunion tour of his classic The The project was truly something to behold for all fans fortunate enough to attend. The short run of dates marked the first time in 16 years that the vocalist/guitarist had performed live with old cohorts James Eller (Bass), D.C. Collard (keyboards) and Earl Harvin (drums), augmented by new co-guitarist Barrie Cadogan, and it reframed in a more modern context dark, moody classics like “Infected,” “The Beat(en) Generation,” and the signature “This is the Day” and “I’ve Been Waiting For Tomorrow (For All My Life).” Yet it’s only now, three years later, that his recording/publishing company Cineola is releasing a Royal Albert Hall-filmed document of the affair—humorously dubbed, a la a leather-clad Elvis Presley in his own ’68 return, The Comeback Special—in separate video, album and 136-page art book forms. “It should have come out sooner, but the pandemic slowed everything down,” sighs Johnson, who just turned 60.

The Comeback Special was filmed and recorded ideally to come out in 2019, he adds of his original best-laid plan. “But it was just impossible, and even in 2020, as well. There were manufacturing problems with the vinyl, and all of the factories had been way behind schedule. Once the pandemic hit, there were all sorts of complications that slowed it down. But thankfully, now it’s almost here.” The various versions are officially available as of today, Oct. 29. Also on sale: four embossed, autographed, hand-numbered art prints, featuring images from the concert titled “Mobilise,” “Globalise,” “Hypnotise” and “Homogenise.” Johnson might have had his chart-topping heyday with two older albums, Infected in ’86 and Mind Bomb in ’89, but he spent a good deal of lockdown not only writing new, sunnier The The material, but also streamlining for 2022 Cineola release The Inertia Variations, the 2017 documentary about his late brother Eugene and the effect his passing had on him. Currently, he also stands at the ready as key soundtrack composer for another brother, the cutting-edge filmmaker Gerard Johnson, which guaranteed him a busy schedule, all through the pandemic.

… With one minor diversion, Johnson reluctantly admits. Last year, as Covid cases escalated in the spring, he wound up in London’s Royal Hospital with a rare—and unusually aggressive—throat infection that engorged his neck to twice its original size, forcing its sliced surgical opening as life-or-death treatment (Johnson posted a post-incision photo online of his unconscious ICU self that is truly not for the squeamish). But as he wryly noted underneath it, he’s always had a high capacity for weirdness. So for anyone out there thinking that they’ve already experienced, and survived, The Day Their Life Will Surely Change, don’t be so hasty, he cautions. There are probably many more to come.

Paste: Talk to me like I’m five. How do you get an ultra-rare neck infection in the middle of locked-down 2020? And in the photo, with your neck surgically slit open, you look almost like a lamprey.

Matt Johnson: Yes! And oh, it was awful! And it had nothing to do with Covid—it was a freak infection, what’s called a pharyngeal abscess, an abscess of the pharynx, not the larynx. And it was a freak thing. They don’t know how it happened, but there were complications from it, which turned into a life-threatening situation. So they had to operate, although I was very anxious about an operation because I didn’t want it to affect my voice. So the way I can describe how it felt—and this is before the operation—is, imagine having a little python wrapped around your windpipe inside, slowly squeezing you to death. That’s how it felt. It was very, very unpleasant, a horrible situation. And it was a strange time to end up in hospital, obviously, at the end of April, early May, because the big first wave, the big first lockdown, had just started. So it was not a nice thing to be in hospital—it was truly very unpleasant. But luckily, there was a very good surgeon who took care of me, and when it was over, that operation, I was exhausted. But I was told that I couldn’t sing for six months, and I wasn’t sure if I would be able to sing again or not. But my voice is okay now.

Paste: What were the first tentative things you sang afterwards? “Mary had a little lamb, little lamb”?

Johnson: Yeah! Something like that! It was a nursery rhyme for my youngest son. “Walking around the garden like a teddy bear / One step, two steps, tickle me under there.” He liked it. And kids love it, because then you tickle the kid and they start shouting and screaming. So that’s probably the first thing I sang, and then I sang some other bits and pieces. But thank God it was a success, and I was able to get back my life.

Paste: How long were you in the hospital?

Johnson: Well, I was only in hospital for a couple of weeks. But I was unwell for a few days leading up to that. And I tried to stay out of the hospital, but I couldn’t—I was too ill. So I went in for a couple of weeks, and then it was a couple of months of recuperation—I felt as if I was about 93 years old for the following three months. So I spent the first month with my youngest son, who was eight—he’s nine now—and me and him would just go for walks and sit by water and feed ducks and birds. And that was lovely—it was very restorative. It was nice to hang out with him and just be very gentle for a month.

Paste: I’m thinking there might be a concept album in there somewhere …

Johnson: Maybe. Or a film. But it’s a funny thing, because the last 18, 19 months have been very strange for most of us, around the world, in different ways. But I think it’s been a time of great reflection for many people, and there has been a lot of negativity. But there’s been positivity, as well, and I think people are probably realizing that there were certain things in life that they took for granted, whether it’s people or places or things. So I think it’s actually been a healthy period of reflection, and hopefully something positive will come out of it. And there is, obviously, a dark side, as in the amount of division we’re seeing in society now. And I personally never use social media. But on it, you just see this terrible intolerance and hatred for people with opposing viewpoints. It’s very worrying. And I’m a great believer—as I’m sure you are—in freedom of speech, freedom of expression, and the democratic exchange of ideas. But when you’ve got this terrible division and absolute hatred that many people have for anyone who has a different point of view, it’s not a good situation. Freedom of speech is not just for the people I agree with, but for everybody. So I feel like we’re on dangerous ground. And I suppose partly, the last 18 months have been very, very frustrating for a lot of people, with a lot of stress, tension, and your actual life being threatened. But then that may just be the nature of social media—how easy it is for people to insult and abuse each other without any repercussions, because people communicate with each other via social media in a very different way than they would face to face. Because most people, when they meet face to face, are rather amiable, and they try to get along. But social media is this very cold, hard and heartless method of communication where people lack empathy and just want to be proved to be right and score points. It brings out a very childish mentality, I think.

Paste: Looking back at your catalog, your songs have almost been guideposts along the way, or warnings. “We Can’t Stop What’s Coming,” indeed. And now there’s nowhere to run from climate change, since mankind has basically doomed itself to extinction.

Johnson: Things do seem to be headed in that direction. And certainly the last 18 months have been some serious food for thought, and I’m sure it’s inspired a huge amount of material. And I’ve been making a lot of notes along the way, myself. But I want to write something very positive if I can. It was always quite enjoyable singing all of my old songs on tour, because at the time they felt very pertinent and very current. But for this time we’re in now, I think people need hope. Although it’s a dark situation, we’ve got to find a way to overcome these terrible, cancerous social divisions that are ripping people apart. Because it seems to be increasing exponentially, year after year. So I’m trying to find a way—a positive way—to get through this, if it’s possible.

Paste: As your saga goes, you were actually brought up around the family pub. And pub culture is difficult to describe to anyone outside of Britain, but you can often sit down next to a total stranger from around the world and have a nice Guinness- or Boddington’s-lubricated conversation with them. Without getting blind drunk and incoherent.

Johnson: Yes. And my brothers and I used to work in the pub when we were really young to get our pocket money, restocking the shelves and doing other stuff. And of course the term “pub” comes from public house, and that’s a lovely term, a lovely phrase—it’s a house for the public, and it’s exactly what you think. As you said, you go in there, you sit in comfortable chairs, and if it’s a decent pub, there could be a fire on in the corner. And there could be many people in there, or not many people, but people go to the pub to be sociable. Most people don’t go to the pub to be unsociable or hostile, although there are obviously the exceptions—there are some people like that. But it’s a nice environment. And our parents were good pub managers, and there was a lovely bar staff that worked there that would babysit for us sometimes, and we were friendly with them and friendly with the customers. And my dad was a good conversationalist and a very friendly man, an interesting man who was very political. And he was very, very comfortable around other people. He could strike up a conversation with most people, and I think I inherited a certain amount of that. I like most people, and I like talking to people, even if you hear a different point of view. And I’ve started to go to pubs again—they’ve reopened. But unfortunately, in East London, a lot of my favorite pubs are closed down, or they’ve modernized them so they’re not so nice anymore. But it’s a great place to do that. You meet your friends, or you go there by yourself, and it’s often a great way of getting a sense of the public mood. As you talk to people, you may learn something, or you exchange ideas, and you agree with some, you disagree with others. But it was certainly an upbringing that I wouldn’t change, and I felt very, very lucky to have such an unusual life, because most of my friends lived in terrace houses and their parents worked regular jobs. But living above the family business, and being exposed to music at an early age, and just meeting a lot of people? It was a good way to develop social skills.

Paste: Did the pub have a jukebox?

Johnson: Yes. They all had jukeboxes. Because we lived in about three or four different pubs over the years—we moved from time to time. But I remember the really good jukebox in The King’s Head, which is a very, very old inn from about the 16th century. And I remember that the jukebox man would come once a month, put in the new singles, and take out the last month’s singles. And of course, me and my brother would be waiting excitedly, because he would let us have the old singles, because they were only gonna be tossed out. And funnily enough, the other week I just picked up a crate from my dad’s old house—I found it back in the garage, just a crate of old singles from those days. There was David Bowie’s “Starman,” Chuck Berry’s “My Ding a Ling,” Hawkwind’s “Silver Machine,” Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out.” It was a brilliant period for singles, that period in the early 1970s. So the jukeboxes were a really big part of our life, in a day before Spoitify and iPods and 24/7 music TV coverage. And you really appreciated the music, because you had to hunt it down a bit more. It wasn’t ubiquitous. Nowadays, you can’t walk out the door without being bombarded by it, from cars, shops, restaurants. It truly is 24/7. In those days, it was a little bit rarer, and consequently much more appreciated.

Paste: You spent some of lockdown composing the score for your brother Gerard’s film Muscle, too, right? Which looks amazing.

Johnson: Actually, Muscle was scored before the pandemic, but the release of it was delayed because of the pandemic. And it’s a great film. You’ve gotta see it. It’s a bit more surreal than this, but it’s slightly influenced by a great film from the 1960s called The Servant with Dirk Bogarde. And it’s really about one person taking over another person’s life, and gradually inveigling their way into every aspect of their life and then just taking it over. So it’s inspired by that idea, and it’s set in Newcastle and features Craig Fairbrass and Cavan Clerkin, and they’re brilliant performances. It’s won some awards for its performances. And it’s a funny film, but it’s dark. And I score all of his films.

Paste: Again, talk to me like I’m five. How, exactly, do you do that? By watching random scenes, or maybe just reading the script?

Johnson: The way that we work is, he’ll show me the script initially, and then he’ll show me the mood for it, just the general atmosphere, and then he’ll send me some music that he liked—third-party music that he thinks might fit the mood. And I’ll listen to that, and then I’ll reinterpret it all. And I like to work 16-track, so I like to keep the options down, otherwise it just gets too complicated. I like to have a limited sound palette, so I’ll use maybe half a dozen different instruments. And on Muscle, it happened to be a mellotron, a mini-Moog, a guitar, and a couple of other things, so I play all the instruments on his soundtracks. And as I score the picture, he’ll be sending me the rushes over, and then I will start creating sound-to-picture, and then he’ll come to my studio and we’ll go through it together. It’s very, very much a collaborative process, and he’s my brother, so we have very, very similar sensibilities and aesthetics. Just similar tastes in many things, like humor and music and film. It’s so easy for us to work together. So for him, this is the fourth one I’ve done. But my ex-partner is a Swedish documentarian, and I’ve done about 10 documentaries for her, and I’ve done documentaries and films for other people, as well. And I enjoy it. I enjoy it because I can be quite experimental and playful, and there’s less pressure, because there’s no huge pressure to be commercial, necessarily, or to reach an audience. It’s tied in with a film, and it’s specific only to that. So it’s something I enjoy, but I only enjoy working with certain people, directors that I like—where I like what they do, but I also have a relaxed relationship with them. I have done some Hollywood stuff, but it doesn’t really interest me, to be honest. Because the more that’s involved, the less control you have. I like to be very creatively involved, but when you’ve got these big-budget projects, there are so many people involved that there are just too many cooks in the kitchen. I like to have a simple, intimate working relationship with the director. We don’t even let the producers get involved—it’s just me and the director, and we sort things out ourselves. Which I much prefer.

Paste: Was there ever a strange visual where you just could not come up with music to accompany it? Like, say, an arctic fox eating a street taco?

Johnson: Well, the hardest film that I scored was Penthouse North, a brilliant documentary by my ex-partner Johanna St. Michaels. She wanted a jazz soundtrack, which I managed to do, but I’m not a jazz musician or a jazz songwriter. So that was a bit of a struggle, and I had to dig very deep to come up with something. But she was very happy with it in the end, but it was hard. And I was out of my comfort zone, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. But it was definitely stressful.

Paste: I was talking to Gary Numan recently, and he actually commissioned a toy Corgi replica of the triangular car he used to drive onstage. I always respected the artists who had great, quality merchandise, as you always sold, if I recall correctly. From your top-quality embossed metal badges on up.

Johnson: He has his own Corgi car now? I didn’t know that! But yeah, we’ve got some really good things now. We’ve got these beautiful collectible postcards, more little enamel badges, we’ve got lots of new stuff. So yeah, we do take a lot of care over the merch, because I only make and sell things that I would like to own myself. If I wouldn’t want it myself, I wouldn’t sell it, and it’s really important to me that our things are well-made and hopefully long-lasting, as well. And you should check out our Radio Cineola downloads on our website. So Cineola is my company, it’s the record company that I own in the U.K., and so this is what all these current releases are going through—The Comeback Special and its soundtrack. But Radio Cineola is what I like to call shortwave broadcasts—it’s basically a podcast that sounds like an actual shortwave radio broadcast. So I’ve done a series of those, and we’re going to be doing a lot more of them, and you can see them all on my site—there are short ones and there are long ones, and we even did a 12-hour live one, which was very cool. I was literally on air for 12 hours, solid, midday to midnight, with Radio Cineola. Listeners should start with Arrival and then go on, and they’re free to download, as well, these podcasts.

Paste: How many different The The cover versions have you heard over the years? And have there been any truly weird ones?

Johnson: Yeah, there have been. There definitely have been. There was a project called The End of the Day. People cover my songs a lot anyway, but we did an album called The End of the Day, which featured all these other artists doing cover versions of my songs in different languages, so that was quite interesting, and that came out in 2017.

Paste: So you’re probably a big collector, too, right?

Johnson: Well, I have been a collector of various, yeah. I’ve got a lot of books and music. I’ve got a huge amount of books, from hardback novels to old Folio Society editions—I love those. I’ve got more books than I can ever read, all in storage containers, so my partner’s always giving me a hard time. And she’s probably right, so I’ve got to get rid of some stuff. Because somebody’s going to have to deal with it, somewhere along the line. So the big question I’ve been asking myself lately is, “Would my kids want that? Uhh, probably not.” So I’m trying to jettison stuff whenever I can …