I joined Paste in 2023 and, in my tenure as editor, this year’s AOTY list is my favorite by far. The publication has been doling out these rankings since 2002, affixing an “Album of the Year” ribbon on the likes of Frank Ocean, LCD Soundsystem, David Bowie, Weyes Blood, Bon Iver, Pharoah Sanders, and many more. Last year, the terrific and bewitching Jessica Pratt took home the top prize. This year, one of the best albums I’ve encountered this decade sits firmly at the head of the class. One artist on this list released four albums in 2025 alone, while another shared their LP by simultaneously releasing all 17 songs as singles.

To populate this ranking, we’ve combined staff picks, review scores, and contributor votes. What we’ve pulled from all of that data is, in my opinion, a comprehensive and exhaustive list of records—titles and genres spanning far and wide, reaching everything from Carolina alt-country and post-R&B to grab-bag pop and Midwestern jazz-rap. Every entry came out between December 1, 2024 and November 30, 2025. Thanks for taking a ride with us, in a year where five previous AOTY winners released a new album. How many of those alumni are back in our praises again? Start scrolling to find out. Here are Paste‘s picks for the 50 best albums of 2025. Let us know in the comments which ones we missed! —Matt Mitchell, Editor

Switcheroo is a dance party of primary colors, Electrix effects, and strange samples (Did you hear the bear attack on the back half of “Dynamite”?) that emerged through Angel Abaya’s careful songwriting and a love of twisted disco shared with co-producer Sean Guerin of De Lux. Together, they warp dance and synth-pop with a post-punk gloom that underscores Abaya’s aestheticized and verbalized absurdity. It makes a song like “Spit” sound deadly serious, sometimes approaching the intensity of Boy Harsher, but once you dive into the lyrics, you realize it’s a sequence of S-words uttered seemingly at random (repeating the word “Surrender,” though, is ominous). “Normalize” has a similar entropy, as Abaya lists rhymes in dulcet tones: “Anesthesia / Euthanasia / Homophobia / Hemophilia / Diphtheria / Arrhythmia / Cornucopia / Pedophilia.” It sounds like clanging, the mental looping phenomenon explored on rapper Emily Allan’s album of the same name. Clanging is un-free association, a space where the poetic resonance of rhyme grows from a funny coincidence into gospel. Even to an observer firmly tethered to the ground, clanging can produce feelings of obvious disorientation but a nagging sense of interrelatedness. But, where Allan locates clanging as a manifestation of psychosis, Abaya dances with it as part of an effort to navigate familiar torments. Pummeling opener “Funny Music” sees her declaring herself funny as she requests your active participation in the clown-audience dyad. What glimpse of pathetic artifice or defensiveness we get is over before we know it with a “BONK.” Then there’s “Tiramisu,” an uptempo thumper with sandpaper vocals Insecurity, exasperation, and conflict aren’t just for the edgy production choices; they’re essential to Abaya’s songwriting. Where she once shared such meditations through pensive indie rock, throwing them through the prism of the “Gelliverse” between more inscrutable takes gives them a little more weight. It’s proof that you can’t get away from them no matter how many friends you invite over for trampoline misadventures, puppetry theatrics, or color-blocking makeovers. —Devon Chodzin [Innovative Leisure]

49. Benjamin Booker: LOWER

Few artists in recent memory have re-invented themselves like Benjamin Booker has on LOWER, an album that will shock its audience. On “SAME KIND OF LONELY,” an audio sample of a school shooting dissolves into a clip of his daughter cooing. The push and pull of violence of LOWER begins to simmer into a kiss amid the “bones and rotting flesh” of your slow expiration on “SLOW DANCE IN A GAY BAR.” “I just want someone to see me,” Booker croons in a twilight-dim hush. “I am beginning to see the beauty all around me.” It’s a swell of clarity on an album full of questions. It’s wounded and aching. A guitar string gets plucked through tender, Kenny Segal-made beats. A keyboard twinkles like a dainty sunrise. Even at its most sacred, LOWER is a challenge. Through the thrums of razor-blade guitars and a dense drumbeat you can feel deep in your lungs during “BLACK OPPS,” Booker insists that “they’ll kill you while you sleep.” There’s a sweetness to “POMPEII STATUES” masking a sinister underglow of swirling, burning caustic drones. The acoustic “REBECCA LATIMER FELTON TAKES A BBC” is named after the first woman and last slave owner to serve in the United States Senate (she was also only a senator for one day) and riffs on self-flagellation, pleasure, and racism (“You watched me from the porch and touched yourself, didn’t you? The pain you must have felt watching me go home at night to love, real love”) and a diss that’ll rattle your insides (“Those eyes, those thighs, were you never much to see? Tired eyes and skin like concrete, she could melt the ice caps with that beautiful smile”). LOWER can make for a maddening listen. It is, all at once, full of air yet claustrophobic. The songs often—and in colorful ways—illustrate breaking points. They’re intimate and brutal, juxtaposing delicacy with wretched, subterranean banalities. —Matt Mitchell [Fire Next Time]

Read: “Benjamin Booker, beyond recognition”

48. Ela Minus: DÍA

I think Ela Minus’ last album, acts of rebellion, is one of the best debuts of this decade. But the Colombian singer’s follow-up, the impossibly great DÍA, is even better. Confident, affecting dance tracks—namely “Broken,” “Upwards,” and “QQQQ”—feed into ambient, atmospheric passages, including the lush fixations of “Combat.” If acts of rebellion established Minus as a subversive, vital artist bridging the gap between New Order and Aphex Twin, then DÍA cements her as a towering digital force. The state of electronica as we know it is fuller because she is making music within it, and DÍA, huge-sounding even in its effervescence, is unforgettable. —Matt Mitchell [Domino]

47. Greg Freeman: Burnover

The best songs on Burnover are suffused with the same oversized emotions as I Looked Out, but they’re leaner, punchier, and brighter. These qualities sound like they’d make for an easy listen, which Burnover can be—it isn’t long before you’re bobbing your head along to the uncharacteristically lax piano jam “Rome, New York”—but even then, the music never lets you settle. As a composer and writer, Greg Freeman has only grown more restless and challenging: his grooves are blocky and slightly queasy; most lyrics demand close study to be properly digested; there aren’t really any choruses to bite into. Most songs, instead, patchwork together epic build-ups, breakdowns, and curious, interstitial interludes that would make the late Sparklehorse mastermind Mark Linkous proud. Glockenspiel and chimes shimmer atop the cacophonous midsection of “Wolfpine” like fairy dust, elevating the Neil Young-ish scorcher to the cosmos. By the end of the “Point and Shoot” breakdown, Freeman is backed only by a screechy violin that drunkenly harmonizes with his parting statement: “She could see the frame, but never the picture / A live round spun, and a split-second flicker broke,” he sings despondently, returning to a verse he’d spat early in the song with a sneer. Instead of rushing on to the couplet that’d capped those lines, he lets that “broke” hang in the air, his weary sigh and simple final word conveying at least as much as—if not more than—the cryptic early verses. Since his debut, Freeman hasn’t shied from pushing his voice past its breaking point, and his new confidence on Burnover only amplifies the album’s emotional reach. —Cassidy Sollazzo [Transgressive/Canvasback]

46. Blood Orange: Essex Honey

Joy is subtle on Essex Honey but sorrow is abundant, as is nearness, leaving, and the album’s feature list, which reads like a group chat, featuring Caroline Polachek and Lorde, Mustafa, Daniel Caesar, Eva Tolkin, Liam Benzvi, Charlotte Dos Santos, Tirzah, and Mabe Fratti. Dev Hynes, who is nearly 40, reaches towards gentleness in a way he didn’t on “Orlando” seven years ago, when he sang, “first kiss was the floor, but God it won’t make a difference if you don’t get up.” With classical motifs feathered into schmaltzy electronica and drum ‘n’ bass, Essex Honey is effusive, vintage, and patchy, with beat switches, fade-aways, and a vocal syndicate not unlike the sensual coherence of Freetown Sound’s slinky, ‘80s-glorifying package. Periods of Essex Honey’s writing and recording, Hynes says, “shared an energy” with that record, because there’s a physicality present—you can “feel the hand and process,” so to speak, on a song like “Countryside.” On “Somewhere in Between,” I am reminded, above all, of the anachronistic, plinking synths in Arthur Russell’s “That’s Us/Wild Combination.” Like Weezer, his affinity for Malcolm McLaren’s “Madam Butterfly” is ever-present in his intentions, but Essex Honey’s best (subconscious) callback is to one of Hynes’ East England neighbors, Yazoo. Specifically, “Only You” emerges every time the synths in “Mind Loaded” wash over me. But on a song like “Scared Of It,” Hynes lets some of the best guitar phrases of his career beautifully unfurl. Since leaving Test Icicles more than 15 years ago, his use of the instrument shows up methodically on Blood Orange projects, most handsomely in the guitar vamps of “Orlando” and most incongruously in the funk chords of “Nappy Wonder.” Essex Honey is a textural dream. —Matt Mitchell [RCA/Domino]

Read: “Blood Orange, between the strings”

45. Addison Rae: Addison

Addison plays with reckless abandon, and that audacious approach is at the core of the album. Lead single “Diet Pepsi” features a smattering of early Lana Del Rey-isms, and leans into the equal silliness and sensuality of a car hookup. Addison Rae whispers in her high register, pleading with her beau to declare his love for her while tangled up in each other’s limbs, while the synths glide overhead. She makes it sound like the difference between life and death. This also isn’t the only song that calls Del Rey to mind; “Summer Forever” recalls vignettes of sun-kissed, sticky skin and the wide-eyed awe of Lust For Life’s “Groupie Love,” where both artists swoon over the mere company of their lovers. This earnestness threads throughout Addison. “New York” is about the millionth love letter written about the Big Apple, but pulling from Charli XCX’s electroclash school of thought sets the album off on a high note. Rae’s gliding harmonies and hyperventilating breaths layer over a ticking bass drum as it mutates from an early FKA twigs demo to a saccharine sibling of Underworld’s “Born Slippy (Nuxx).” Some may say money can’t buy happiness, but Addison raises an eyebrow at that idea. The hedonistic anthem “Money Is Everything” inquires: What would it sound like if Britney Spears and Kreayshawn made a song together? Rae plays off the track’s cheekiness with such sincerity, giggling through lyrics about requesting the DJ to queue up some Madonna, that it’s irresistibly charming. Even in the more melancholic scenes of the record, she spends them in a meditative, optimistic state. The R&B forward standout finale “Headphones On” functions as a succinct mantra for when times get tough; grab your earbuds, strut to the corner store for some Marlboros, and weather the storm. “You can’t fix what has already been broken,” she sings, manifesting brighter skies. “You just have to surrender to the moment.” Maybe pop music can learn a thing or two from Addison’s radical optimism. —Jaeden Pinder

44. Ethel Cain: Perverts

It’s a shame when everyone seems to talk around (not even about) one of the year’s best releases—and it certainly doesn’t help when the artist also shares what she’s deemed a “real” album in the same year, pulling the focus of more fairweathered fans away. Regardless of whether you first checked out Ethel Cain’s January “release” Perverts just to hear a supposed middle finger to a more mainstream fanbase and a label situation the artist wanted over and done with, it doesn’t take away from the fact that it remains Hayden Anhedönia’s most staggering full-length work to date. Mining inspiration from the drone and ambient north stars she’s proudly cited as favorites since 2021’s Preacher’s Daughter first pulled her fully into the spotlight (if you’re a Grouper fan, this is likely high on your personal ranking for the year), Perverts is an atmospheric exercise, digging to the filthiest, most cryptic core of her sonic obsessions. The grinding whir of “Houseofpsychoticwomn” and bleating strings of “Pulldone” might have driven all the heated conversation for those less interested in Anhedönia’s more avant-garde tendencies, but there are moments of pure salvation (the climax of “Onanist” or the sparse beauty of closer “Amber Waves”) that could convert any skeptic, if they have the patience. Let them talk all they want. I’ll spend my time kneeling at Perverts’ altar again and again. —Elise Soutar [Daughters of Cain]

43. keiyaA: hooke’s law

On hooke’s law, keiyaA’s production is more concrete: less ethereal, more corporeal. Whereas Forever, Ya Girl’s arrangements were often wispy and intangible five years ago, this album grounds keiyaA in music that is sturdier, heftier, and fuller. Take the Auto-Tuned vocal runs of “think about it/what u think?,” the virtuosic jazz drumming on “take it,” the crisp syncopation in the second half of “until we meet again,” or the resonant low-end of “this time” for example: The instrumentation is direct, much like the excavations and interrogations of self that supply its lyrical content. Collectively, everything on hooke’s law works in tandem to underline keiyaA’s artistic pluralism. Since her debut, her music has defied easy, convenient explanations, much to its benefit. These songs are an amalgam of woozy electronica, labyrinthine jazz, bass-heavy hip-hop, arty pop, and soothing R&B. Relatability is often regarded as an artistic paragon, an ideal that all songwriters, especially the biggest and richest among them, should aim for. On occasion, that leads to a diluted body of work. Instead, keiyaA presents an alternative, one where inscrutability, and the ensuing self-examination that follows, is an equally worthy pursuit. Some things will always be unknown. On hooke’s law, keiyaA illuminates the shadows. What we’ll find there is yet to be discovered. —Grant Sharples [XL]

42. Tobacco City: Horses

In a year teeming with so many excellent Americana albums, few have stuck with me like Tobacco City’s Horses. There are 12 people hammering away on these 12 songs, but Chris Coleslaw and Lexi Goddard’s shared alchemy powers the music. Horses is Gram and Emmylou, but Horses is also every no-name bunch of rabble-rousers in smalltown tonks. It’s pure old-school country paired with dangerously great and experimental soundscapes, like the spiraling freakout jam on “Mr. Wine,” which gives Tobacco City an unpredictable edge. Goddard’s harmonies on “Autumn” are achingly perfect, while the barroom waltz of “Bougainvillea” spans for miles and miles. “Buffalo” is a shit-kicker’s dream, while winces of Jim Becker’s fiddle and Andy “Red” PK’s detailed pedal steel rummage in the gasoline-drenched splendor of “Time.” I’m struck down by the tangled beauty of Tobacco City’s pastorals. Horses gives and gives and gives. —Matt Mitchell [Scissor Tail Editions]

41. Agriculture: The Spiritual Sound

The Spiritual Sound is my favorite best metal album of the year. It’s not abrasive or coarse, instead splendid and weird and possible. These songs tug on euphoria and affirmation more than catharsis, and Dan Meyer and Leah Levinson’s complementary voices and cerebral ideas fuse into each other. On side one, the band reckons with monotony in big choruses and punky, overdriven, headlong abandon (“Micah (5:15 AM)”), which gives way to this cleansing, fascinating plenty of stillness (“Serenity”) on side two. Meyer’s writing is almost supernatural, pawing at godly obsessions, while Levinson’s expressions are tonally resilient. That potent collaboration unfolds in delirium on “My Garden,” an intro track that detonates upon its awakening. Throaty, animalistic vocals curdle around lasering guitars. “My ears are burning, my body is burning, my mouth is burning,” Levinson sings. “Death is the ultimate fucker, death is the ultimate.” Perfectly, the track opens up and the guitars punch but don’t punish. Meyer attacks the bridge, “Now I know who’s in my garden, now I know what form it takes. Gone but never quite forgotten, I have found a resting place,” and the essence of Agriculture—a band agnostic to just one fashion—properly unfurls, as patches of shoegaze, post-rock, screamo, and thrash penetrate the black, persisting sirens. “Flea” is similarly unpredictable and vast, tearing through a monstrous drum roll and splintering guitar, all while Levinson’s voice sustains in the underbelly of Meyer’s violent hollers. “Living rooms, they’re born again to men like ghosts attached to teeth,” she hums. “The words sting in passing, more or less.” But the vocal contrasts in “Flea” are replicated in tangential arrangements. The song’s true middle pacifies brutality with a sprawl of hazy bedroom chords, only to be shocked back into the torrent by Meyer’s charred, reflective yawp: “Where trust and love fail, fear makes a map. You followed it.” “The Weight” nauseates with a colossus of noise that’s disharmonious and deadlocked in breakneck riffs and protracted, bitter screams, while the phrasings in “Serenity” are more glowy, revealing Agriculture’s poetry: “My god is enduring this world every day. Each day, I leave God to it. No death could be worth escaping the timbre of this pain.” —Matt Mitchell [The Flenser]

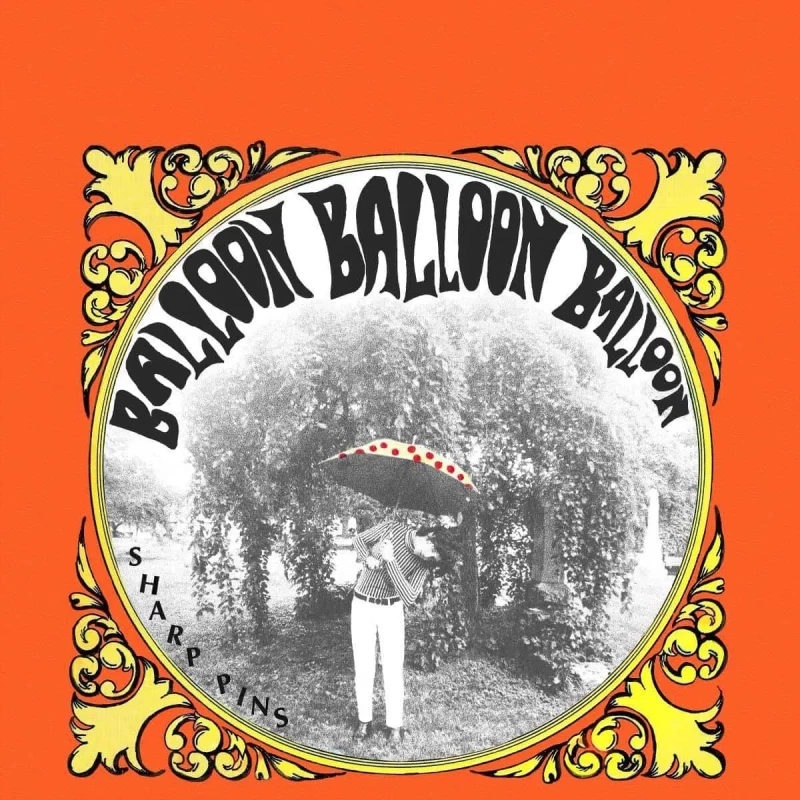

40. Sharp Pins: Balloon Balloon Balloon

Sharp Pins is music that sounds like the bubblegum stuck to the back of a Topps card, performed by an antsy, zooming ingénue infatuated with Zappa, Revolver, and Television Personalities. This isn’t revivalism or hero worship but evangelism—a mod-styled, mop-topped boy-wonder feeding his passé creations into a 4-track and mangling the shit out of them. Kai Slater’s ideas disintegrate in your ears: the flecking, dopey harmonies on “Gonna Learn to Crawl” dole out contact highs; the head-bobbing pop of “Queen of Globes and Mirrors” sustains as a lucid, psych-folk nebula; “Ex-Priest / In a Hole of a Home” goes full atomic with crusty bursts of indelible hooks; “Popafangout” spits out a 12-string tremolo written in cursive; Slater’s falsetto on “Maria Don’t” is so gentle it might break if you hold it too long; the riff-driven mutedness of “All the Prefabs” is squarely the whole, swaggering, glammy point. Remember: this record is a cherry-dipped fuzzscape 21 stories tall. Slater covers a lot of ground, and he covers it quickly. My favorite sound in the world is Roger McGuinn’s bright, 12-string phrasing. Slater argues that McGuinn’s tone is “teeting on the edge of exploding.” It’s no wonder you can hear the Byrds’ style of lead lines all over Balloon Balloon Balloon, in songs ready to go kablooey from even the slightest amp rub, “I Feel Fine”-style. —Matt Mitchell [K Records/Perennial]

Read: “Kai Slater is gonna save rock and roll, one Sharp Pins album at a time”

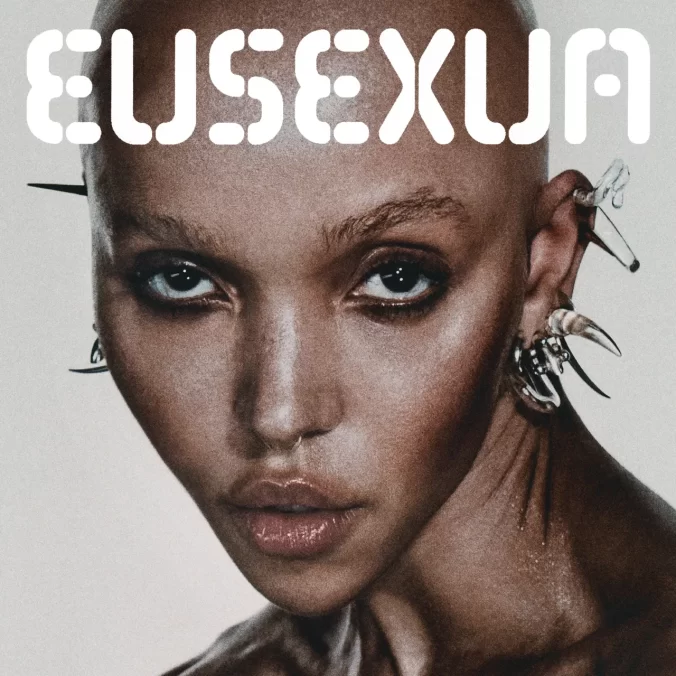

39. FKA twigs: EUSEXUA

The title of FKA Twigs’ EUSEXUA is the state she’s in: birthing and penetrating through lining toward a new enmeshment between human and machine. Cold machinery and warm flesh touch: intertwining, rooting into one another as flesh and raw metal crystallize into a new element. Her vocals are supple and tender (“Eusexua,” “Sticky,” “24hr Dog”) when not ecstatic or revving (“Room of Fools,” “Drums of Death”), moving with and against rigidity, tempered by unexpected, mechanistic spasms of unrecognizable fluidity. These interruptions—whether the intense interjection at the end of “Sticky,” the jungle syncopation concluding “Striptease” with a reiterated, accelerated verse, or the rave beat invading “Keep It, Hold It”—keep us on watch, as if the last remnants of a pre-cybernetic humanity are recoiling from the immanent confluence Twigs prophesies. “Shed your skin / Rip your shirt / Flesh exposed… Hard metal, silver stiletto / Devour the entire world / Fuck it, make it yours,” she sings on “Drums of Death.” EUSEXUA is a tantric future, Dionysus dancing toward the post-anthropocene. —Andrew Ha [Atlantic/Young]

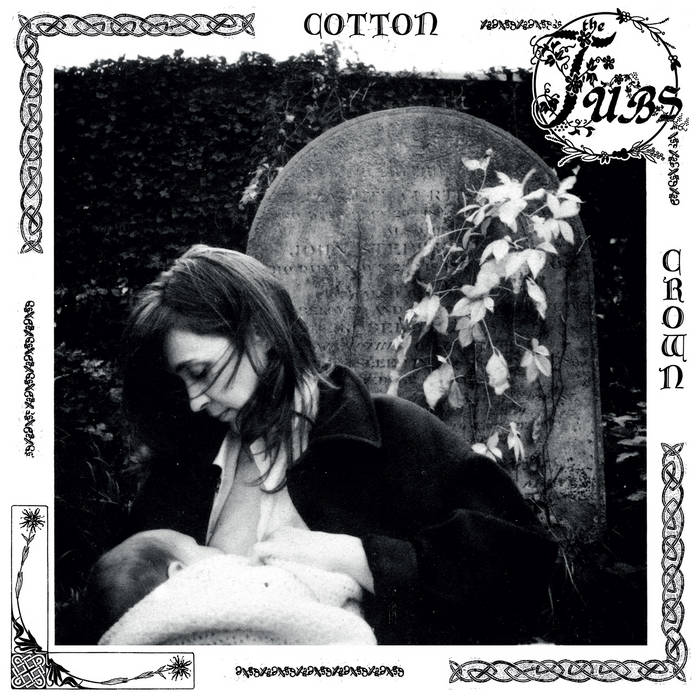

38. The Tubs: Cotton Crown

Here is the charm of Cotton Crown: The juxtaposition of Owen Williams’ words with the bright jangle rock within is what makes the album an enticing listen. Guitarist George Nicholls, bassist Max Warren and drummer Taylor Stewart play with a high-level intensity and togetherness, and the music they make will sound familiar to anyone who might’ve put “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now” next to ”I Believe” from Life’s Rich Pageant on a mixtape. The ringing guitars and high BPMs make Williams’ morose storytelling go down smoothly, like finding out a pint of Guinness is not as heavy as it seems. Even when the Tubs are channeling Johnny Marr on “Narcissist,” or Bob Mould on the yearning “One More Day,” the music sounds fresh—despite the obvious borrowing from sounds made popular on college radio stations during the Reagan years. All the while, the Tubs’ music is never bogged down by the lyrical content. It’s never dour, always moving. “Strange” is what ties all of Cotton Crown together, where the “subterranean world of grief” is laid bare in Williams’ own roundabout way. It’s a song he took a decade to write, afraid of sounding too corny on the mic. It’s the most autobiographical song Williams has written so far, one that features his own sideways humor about the weirdness of grieving, for both himself and the people around him. It also happens to be the sunniest-sounding track on Cotton Crown. And what does Williams have to say at the end of this momentous song about his dead mother, the one that took him so long to write? “I’m sorry / I guess this is it.” —Jeff Yerger [Trouble In Mind]

37. Bad Bunny: DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS

Benito Martínez Ocasio—AKA Bad Bunny—thrives best when the album’s focus is close to his heart. After his 2023 record nadie sabe lo que va a pasar mañana, I worried that the Puerto Rican trap star had been lost to Hollywood. He was dating a Jenner sister and making songs about fame, losing his relatable touch. But with DeBí TiRAR MáS FOToS, we get to know the real Benito: the one who declared as a kid that he was a “salsero” before becoming enamored with reggaeton. He’s a wistful and sensitive soul who acknowledges that with his new life as a megastar comes some sacrifices, such as losing his longtime partner, and is learning to not lose touch with the things that truly matter. Released on the eve of Three Kings Day, DeBí TiRAR MáS FOToS feels like stepping into a Puerto Rican holiday party, one with salsa (“BAILE INoLVIDABLE”), pleneros (“CAFé CON RON”), and some “PiToRRO DE COCO” to celebrate. It’s a lively celebration of boricua culture and one that reminds us not to take it for granted, with Martínez Ocasio warning that with wealthy Americans moving into our island for a tax break, we’re being priced out and forced to move elsewhere, diminishing what turns Puerto Rico into the isla del encanto. —Tatiana Tenreyro [Rimas]

36. Ninajirachi: I Love My Computer

I Love My Computer teems with zillennial nostalgia, both in subject matter and sound. It’s autobiographical, with Ninajirachi telling the story of her musical coming-of-age, thanking the computer that made it possible. It’s a meta, ultradevotional, music-about-music record, and the fact that it was created entirely on a computer is the point. There are only so many of us who grew up in a time before parents realized iPod Touches were basically phones, and Nina Wilson writes from inside that exact window of unsupervised digital childhood. Much of the record carries the DNA of early 2010s EDM and electronica, the era of blown-out beat drops and maximalist production that imprinted differently when you heard it at 11 instead of 21. I Love My Computer sounds like the natural result of that kind of early exposure—elastic, impressionable. It makes me think about the first time I heard the A-Trak “Heads Will Roll” remix (I was ten) and how, in that moment, I learned that a song actually could swallow you whole. I Love My Computer is one giant mix of hyperpop, electroclash, and EDM, and the music is so endlessly frenetic that you don’t even have time to think about breathing. “Battery Death” is pure anarchic, Zedd-era maximalism; “Delete” could easily slot into the how i’m feeling now tracklist or a PC Music compilation. “London Song” opens the record with a blown-out, crunchy, what-The-Dare-thinks-he’s-doing kind of bass thump. It bleeds right into “iPod Touch,” a cutesy, sped-up bop referencing not just the titular device but its Pikachu case and the tiny rebellions it enabled. By sidestepping the traditional skill hierarchies she inherited, Wilson shapes a unique and fascinating EDM/electronica world. Ninajirachi is both the multiverse and its maker, possessing the all-consuming scale and the singular perspective, both of which anchor I Love My Computer from the inside. —Cassidy Sollazzo [NLV]

35. Kathryn Mohr: Waiting Room

It doesn’t matter what time or place in which you choose to listen to Waiting Room, Oakland-based experimental artist Kathryn Mohr’s Midwife-produced third record. Despite the hour and location you choose to immerse yourself in the music, it will transport you to the middle of nowhere in the middle of the night. It lives smack dab in the middle of a wide-open prairie or sinking like a stone to the bottom of the ocean—just anywhere the light won’t find you, leaving a creaking bench beneath an organ on the title track or the staticky screech of Mohr’s guitar on a song like “Elevator” stand alone as the few tangible sounds guiding you blind. Drenching a classic alt-rock fuzz in Flenser-friendly soundscapes, Mohr’s created a beast of a record that echoes against cold cave walls, coos like the ghost trying to charm its way into you, ignites without warning and sets the darkness ablaze—with no promise of transporting you back. It might be for the better. —Elise Soutar [The Flenser]

34. Panda Bear: Sinister Grift

Sinister Grift may feature some of Noah Lennox’s best work since “My Girls,” but none of it is reheated. There isn’t a song here that will trap you in Smiley Smile dispatches like “Comfy in Nautica” or “Bros” did 18 years ago. Instead, the triptych of “Just as Well,” “Ferry Lady,” and “Venom’s In” brightens a new environment in Lennox’s know-how, reminding me of the way “Choo Choo Gatagoto” splinters into “Owari No Kisetsu” on Haruomi Hosono’s Hosono House, where the melodies fold into different bastions of catchiness and rollick through picture-perfect sequencing. Sinister Grift is more textbook and recognizable than most of Lennox’s previous efforts, full of well-crafted, old-school rock motifs and kinetic immediacy. Though he went three-for-three on pre-release singles, the first 12 minutes of Sinister Grift is among Panda Bear’s finest work, especially the 20/20, “Time to Get Alone” and “I Can Hear Music”-conjuring opener “Praise” and the left-field dub-pop that reinvents the conventions of “50mg.” Too, these songs offer a look into a vulnerable side of Lennox we’ve rarely encountered, as he fixates on love through different intervals of separation, be it divorce or the things that were said but not meant. This music isn’t broken, though; only bruised. —Matt Mitchell [Domino]

33. Titanic: Hagen

The duo behind Titanic, Mabe Fratti and Hector Tosta (aka I. la Católica), have long lived in the mixed-genre experimental scene. As a soloist, Fratti’s songs bounce between free jazz and chamber pop, running between structure and unboundedness. Her collaborative projects with Amor Muere collective members and Gudrun Gut are similarly exploratory and complex. Tosta has contributed guitar to a variety of bands performing everything from punk to progressive folk rock, each project thornier than the last. And together, the power couple have been on a tear ever since they properly joined forces under the moniker Titanic roughly five years ago. Their songs are filled to the brim with jerky, arrhythmic guitar, cello, and drum lines, each more memorable and unexpected than the last. On their second album, Hagen, the pair’s exhilarating rhythms and soaring vocals create an edgy, foreboding style of experimental pop that’s both catchy and challenging. “Escarbo dimensiones” starts with muffled syncopation and grows into a symphony of strings and satiny guitars that would feel right at home in an old action flick about international spies or cyborgs gone rogue. Something this glossy could easily come off as gauche, but Fratti’s prismatic voice is rich with emotion as she swings from word to word. “Te tragaste el chicle” first sees her vocals spread evenly over a slow, thumping ‘80s ballad beat. She sings at a bright, level volume before belting, “Se que no me van a perseguir” (“I know I won’t be chased”). The sprightly guitar line beneath her climaxing vocals underscores the sense that Fratti’s making a much-needed declaration. As much as there is to fear in this world—she cites technological messiahs and armed monkeys—she sees no value in running anymore. The line can be read as either resignation or resolution, to give up and accept fate or stand one’s ground against enemies who aren’t really after you. —Devon Chodzin [Unheard of Hope]

32. Perfume Genius: Glory

Glory is bold and tender, moving through flourishes of optimism and fear, and unapologetically overwhelming whatever space it lingers in. While there is always a longing in Perfume Genius’s music, Glory presents a version of Mike Hadreas that’s more grounded in the pocket of his ever-evolving identity. His music is as immediate as ever, but the album shines with a fresh and unrelenting gloss: “Capezio” utilizes an uncanny tremolo to reintroduce Jason, a frequent moniker for silhouettes of men in Hadreas’ stories, while “Clean Heart” glistens with a bittersweet sparkle akin to “Nothing At All” from Set My Heart on Fire Immediately. These atmospheres are quite intricate, and there is surely a sea of creativity in collaboration, as musicians who have become integral parts of the Perfume Genius project—Tim Carr, Jim Keltner, Meg Duffy, and Alan Wyffels—contribute immeasurably to the depth in texture and movement of the record, decorating the careful path laid forth by Hadreas. Despite its lyrical minimalism, the world Hadreas remembers during “Full On” is vivid, soft and surreal, relying on extended instrumental passages for exposition. The abstract world of “Hanging Out” swims in restraint, passing through deconstructed, post-industrial stretches, moving like an interpretive dance scattered across a minimal sonic collage. Hadreas, alongside his band, can vibrantly impress his shape into the most ineffable vacuum, and Glory might be his most spectacular demonstration yet. —David Feigelson [Matador]

Read: “The everything of Perfume Genius”

31. MIKE: Showbiz!

For MIKE, music and community are intersecting lines on the same chart; they’re two worthy pursuits that produce a symbiotic effect for their counterpart. On top of managing the Young World festival and his 10k record label, he is a producer for various artists, releases music under his dj blackpower moniker, and still makes time for his work as MIKE. More than any of his other albums, Showbiz! embodies the communal spirit that its creator so frequently espouses. His insular, funhouse-mirror instrumentals permeate the record like viscous syrup spreading over a tall stack of pancakes. But here, he sometimes cedes production duties to likeminded artists such as Laron (“Showbiz! (Intro)”), Salami Rose Joe Louis (“Zombie pt. 2”), and Surf Gang’s Harrison (“Belly 1”). Each understands the gravitational pull of MIKE’s work, a tapestry of woozy samples, shimmering keyboards, and shapeshifting drums. Every element orbits his unmistakable voice, built on a compelling hybrid of somnambulant delivery and dextrous wordplay. As Showbiz! suggests, that’s what MIKE is ultimately doing this for. On “Artist of the Century,” he ends the chorus with one of the album’s most indelible lines: “I been puttin’ up with strife since a youngin / The prize isn’t much, but the price is abundant.” Even if underground hip-hop is far from the most lucrative career path, making art and finding your faction can yield different kinds of riches, ones that value the soul over the bank account. MIKE understands that intuitively, and it’s clear from his craft alone. —Grant Sharples [10k]

30. SML: How You Been

I dig on SML. The Los Angeles free improv quintet (Anna Butterss, Greg Uhlmann, Booker Stardrum, Josh Johnson, and Jeremiah Chiu) make jazz records that sound like someone set a stack of Can, Susumu Yokota, and Fela Kuti albums on fire and tried dropping a needle on the remains. Their debut LP, Small Medium Large, was a gas in 2024; “Three Over Steel” is still a huge tune. You can tell these players were regulars at ETA before it closed. The collective’s new album, How You Been, is billed as a blend of kosmische, house, acid jazz, Afrobeat, and techno. “Taking Out the Trash” begins like a pulse in a cut, with Johnson’s saxophone skittering on the topline and Butterss’ crunchy bass tone colliding with Stardrum’s snare below it. Uhlmann’s skronking guitar chimes in before the whole thing erupts into a funk voice that streaks in every which way but parallel. It’s like listening to the threads of four or five different songs all unravel at once. I was going to shout out Uhlmann’s effected guitar playing on “Chicago Four,” but then I realized I needed to shout out Booker Stardrum’s sweeping drums, too. And then Anna Butterss’ throbbing bassline came into view, as did Josh Johnson’s sludgy horn shots. And then arrived Jeremiah Chiu’s synth passages that play a song of their own. What I’m getting at here is: SML brings new meaning to the idea of a “collective.” Everything they do is in lockstep with each other, even when it sounds like every member is doing something impossibly different. “Chicago Four” reveals an almost hypnotic loop of contrasts. It’s as much an industrial synth-pop song as it is a jazz-funk lick. The music is all over the place yet never out of chemistry. I know improvisation is essential to SML, but there’s gotta be a word for whatever exists beyond that. It’s hard to categorize whatever the hell is happening on How You Been as anything but one of a kind, impossible. —Matt Mitchell [International Anthem]

29. Jane Remover: Revengeseekerz

Revengeseekerz is the most straight-forward Jane Remover release yet, and sort of a combination of their poppy 2024 singles and Ghostholding, though this record is lighter on the rock part. For 12 songs, Jane is a self-referential tornado rummaging around in a maximalist ether, embellishing micro-genres and splitting continuums into their own playground of crushing techno, EDM, and blazing hyperpop. The intervals of stillness that balmed Census Designated have vanished, as Jane stacks diss upon diss, vaunting through rap templates that have been submerged beneath mayhemic, static-walled cyphers. “There’s two of me, I’m cloning out,” they bawl on “TWICE REMOVED.” “Dead man flexing, show some ass now.” Revengeseekerz is not just a horizon of touch or an appetite for wrongdoing, but a portal. From the haunted, “of course you can touch my body” anaphora in “angels in camo” to the “bitches dick suck then they go and bite my sound” sneak in “Dreamflasher,” Jane presents a complicated, scornful world. These songs contradict themselves, peddling a fast living while the bodies in motion ache to settle. “TURN UP OR DIE” jerks and tremors like edits in a grindhouse cut-scene, dropping gauzy, compressed melodies into a melange of chipped and shredded circuitry. “Give dead bitches proper sendoff,” Jane raps, before the song crescendos into the best beat drop of 2025 so far. Out of a pocket of futuristic, siren synths awakens a motto: “Make some noise, do it live, save the file, do or die.” The Jane Remover we hear on Revengeseekerz is flawed and vulnerable, even in the perfect, muted melee of their greatest curation yet. This music hemorrhages with pleasure and regret, yet it aches just to love. Fast living, pop stardom, fandoms, changing cities—it’s all a gas and it all unravels. Second guesses come aplenty; drugs help put the room back in color. —Matt Mitchell [deadAir]

28. Hannah Frances: Nested In Tangles

The fenced-in harm across Nestled in Tangles makes for a difficult listen. Even the album’s conclusion suggests that death and tragedy have inescapable perminance. Hannah Frances never reaches for catchiness, only that which soothes the bedlam written within her. “The ways I’ve carried the weight of your absence, reaching for you when I needed you,” she speaks to us, in a spoken-word comedown draped with the sounds of chattering children and music-box hums. “And I will keep reaching, to live here, in the heavy.” The idea of what’s gone and what’s given is a stubborn, angry vibration. Sometimes Frances’ knotty, faraway abstractions (“I reach through limbic estuaries, casting shadows along the entropy and chaos of memory”) compress into clearness and departure (“If there is a way out, let it be through me”). But sometimes they don’t. If Keeper of the Shepherd argued for loss prompting growth and newness two years ago, then Nestled in Tangles concedes now that life-spanning hurt is not to be defeated, only transformed. I return to one sentence in particular, which seems to fall out of Frances like an unhurried tome, when I am desperate for brightness: “It takes living and losing to know what matters.” From the clatter of taut, orchestral trappings emerges a stillness. Nestled in Tangles, unclothed and adrift, shelters in the necessary. —Matt Mitchell [Fire Talk]

Read: “Hannah Frances lives in the space between”

27. OHYUNG: You Are Always On My Mind

Nothing on You Are Always On My Mind fits together perfectly. Assemblages of generic string loops and prominent drum production mix with a litany of samples and entrancing vocals, all slightly out-of-step with each other. It feels like musical Jenga, where if any one feature slips too far behind, the entire structure could crumble. There’s a Tirzah-like murkiness crossed with the emotional vocabulary of more eaze. Even textural differences feel unnerving: “no good” balances attention-yanking drums with legato string passages, and each pointed drum hit feels just ahead of any change in the strings. Skittish electronics dart overhead, following their own rules, as Lia Ouyang Rusli sighs, “Anyone can see / I’m no good for you.” She represents a dialogue between her trans self and a prior self, riddled with put-downs designed to suppress. It feels like water pressing against a dam, chipping away at the masonry with every shift of the current. Rusli’s hip-hop roots are essential touchstones that complicate the pop romance from which she starts. Rusli’s first two solo works as OHYUNG, Untitled (Chinese Man with Flame) and PROTECTOR, are collages of rap and dark, ambient pop that are as personal as they are rich with commentary. You Are Always On My Mind lands somewhere between the hauntological dance music of DJ Sabrina the Teenage DJ and the pensive pop of Astrid Sonne. Rusli’s uncanny splices can be of film clips on “id rather be a ghost by your side than enter heaven without you,” babbles on “i swear that i could die rn” or any the juxtaposition of drum cycles and string flourishes on “no good.” You Are Always On My Mind traffics in the uncanny to present the heightened experience of transition, where everyday moments of panic or celebration often come with an extra coating that turns the notable into the otherworldly. —Devon Chodzin [NNA Tapes]

26. Anna von Hausswolff: ICONOCLASTS

Anna von Hausswolff’s music is an accumulation. On ICONOCLASTS, she is working with an expanded palette of sounds including strings, woodwinds, and rock instruments. It’s a return to the more rock-oriented sound she experimented with pre-All Thoughts Fly, a collection of pipe organ instrumentals. “The Whole Woman,” for instance, begins by layering in a drum beat, a drone, strings, her pipe organ, a guitar, synth melody, and, finally, the saxophone—all in the first minute. Her songs, similar to metal, often span five, six, or seven minutes, taking their time coming to a rupture before dropping out into a sparkling saxophone solo or mournful organ notes. The title of the record, ICONOCLASTS, invokes destruction. van Hausswolff wrote and recorded the record while going through a breakup, although this music sounds more like a battle cry than an expression of despair. “I’m breaking up with language in search of something bigger than this,” she sings on “Stardust,” borrowing from gospel, trance, and post-metal. Many of the songs follow the oft-meandering path away from mourning. “Aging Young Women” joins a recent pantheon of female songwriters untangling their complicated feelings about motherhood, be it Tove Lo’s defiant rejection of suburban parenthood or Oklou’s anxious anticipation of the day her child will leave the nest. “The Iconoclast” finds von Hausswolff in the push-and-pull between routine and self-destruction, “seeking out answers in the wrong places, it’s expensive being alive.” But she is just as often defiant, even ecstatic: “Listen to me: I’m stronger than I seem, ‘cause I’m built for this huge emotion.” —Karly Quadros [YEAR0001]

25. Jim Legxacy: black british music (2025)

Braggadocio abounds throughout, but black british music mostly concerns itself with tales of economic strife, upward mobility, houselessness, romantic yearning, and familial melancholy. “issues of trust” finds Jim Legxacy in ballad mode with orchestral string flourishes, finger-picked acoustic guitars, and introspective lyrics about his strained relationship with his father: “I still can’t talk about it,” he admits in his swooning timbre. Meanwhile, the emo-tinged dembow bop “sos” wrestles with the difficulty of watching the one you love chase after someone else. “He won’t take you out / I know you’ve asked a thousand times,” he sings, his emotive voice perched evenly between desperation and determination. At the same time, these new songs demonstrate Jim Legxacy’s refusal to repeat himself. While black british music largely adheres to the Afrobeats-emo fusion he cemented on homeless n***a pop music, he adapts that blend in fresh ways, whether it’s through acoustic balladry (“issues of trust”), lush alt-pop (“‘06 wayne rooney”), or anthemic Britpop (“dexters phone call”). It also helps that Legxacy understands the power of brevity; most songs hover around the two-minute mark, and the whole project blazes by in less than 35 minutes. Coupled with the sheer amount of ideas he manages to pack into a single track, black british music encourages endless re-listens with plenty of minute details you maybe didn’t notice on the previous go-around. There’s the gliding, cushiony synth bass on “d.b.a.b”; the pitch-shifted vocal samples in the background of “big time forward”; the soft, fuzzy coating of the guitars on the dexter in the newsagent-featuring “dexters phone call.” There’s a lot to take in, but never is it overwhelming. It ensures a longevity that makes the replay button all the more enticing. —Grant Sharples [XL]

24. Saya Gray: SAYA

In 2022, Saya Gray’s debut album, 19 MASTERS, felt like an asymmetrical launch pad for art-pop’s next savant. And her EPs, QWERTY and QWERTY II, displayed an ability to make stripped-back noises sound larger-than-life. SAYA is confirmation that her music is its own kind of cinema. These songs are spiritual, even in their cell-splicing beats, reverb sonar and drive-you-mad transitions; the guitars are intricate and the rhythms lope and twang through wounded frames. Gray’s classical background (her mom founded the Discovery Through the Arts school in Toronto and her dad is an acclaimed trumpeter) makes for good context, as SAYA is its own body and brain, a breakup exercise full of epic, idiosyncratic stories of farewell and mourning cut up into an all-encompassing and all-evading menagerie of trip-hop, psych-folk, prog-rock, glitch-tronica and dubby fusion. Written on a retreat to Japan during the comedown of 2023, Saya Gray has colored reinvention in ten stages of grief, setting nebulas aglow in the dust, in the bizarre and in the bold. —Matt Mitchell [Dirty Hit]

23. Hayden Pedigo: I’ll Be Waving As You Drive Away

Releasing a new album every two years might not seem as prolific as the output of an artist like Guided by Voices or The Reds, Pinks & Purples, but Hayden Pedigo’s productivity numbers are impressive. The Mexican Summer signee has been putting out solo records every other year, and his newest LP, I’ll Be Waving As You Drive Away, marks his fifth in eight years. But what’s even more gratifying is that his quality/quantity ratio is perfectly saturated, as every record arrives brimming with impossibly good and intricate guitar compositions. I’ll Be Waving As You Drive Away is the third and final installment of his self-coined “Motor Trilogy,” following behind Letting Go (2021) and The Happiest Times I Ever Ignored (2023). Now, I know what you’re obviously thinking… Yes, the title of this record is clearly a Little House on the Prairie reference. Even though our mothers probably grew up loving that show, it’s even more niche now that streaming has outmuscled syndication. Nevertheless, Pedigo is as referential and cultural as they come. I mean, his last record was titled after a Doug Kenney quote. Pedigo is part-man, part-myth, part-Texan, part-picker, and part-everything-but-the-kitchen-sink. His music is as warm as it is challenging—a paradox of storytelling that is personal yet world-consuming. For about seven years now, I’ve been trying to put people on to his music, and I think his newest project might finally (and rightfully) put him over. I’ll Be Waving As You Drive Away is inspired by everything from Bladee to Led Zeppelin, providing a total and affectionate rewrite of what instrumental could and ought to be. Pedigo may have left Amarillo for Oklahoma, but the Southern tapestry of a song like “Long Pond Lily” could have only been woven by somebody with his feet always in two places. Did someone give Ry Cooder a tab of acid? Hayden Pedigo makes guitar music without stereotype. —Matt Mitchell [Mexican Summer]

22. Model/Actriz: Pirouette

Pirouette is not just a collision of Kylie Minogue stanning and rock and roll downpours—it’s an album for the middle-of-nowhere-born queer kids who worshipped and loved behind closed doors. Model/Actriz’s music tends to a younger self’s heart, as coming-of-age scriptures chasm amid the ocean-shaking, back-arching rapture of “Doves.” It’s affirming to hear Cole Haden become the hero of his own story by being kind to the inevitability of retrospect. Heavy is the head that bears the memory, and Pirouette is diaristic and confrontational, even in dissonance—it’s, as Haden buzzes during “Cinderella,” “astonishing, utterly divine, exhilarating, preciously sublime.” On Pirouette, Model/Actriz dirty Dogsbody’s tabula rasa. It’s a tapestry of indulgence, as bravado turns into vulnerability and shame is silenced by a command of self. The metallic, clanging “Poppy” features the foursome’s first-ever harmony, and the folky “Acid Rain” and the breathy, slinky “Baton” both fall into similar form. There are techno and house influences on Pirouette, but one of the band’s biggest reference points this time around was Janet Jackson, whose Control and Velvet Rope albums have influenced everyone from Amaarae to black midi. But don’t expect to hear a “Nasty” dupe of any kind, as Model/Actriz look to the nooks and crannies of Jackson’s music for whims, as if they’re noticing something that an untrained ear might miss. As a result, Pirouette sounds like the mechanical parts of pop songs getting blown-out, as if the music Model/Atriz make is a deconstruction of the music they’re listening to. —Matt Mitchell [True Panther]

Read: “Model/Actriz: Spectacles, scars, and survival”

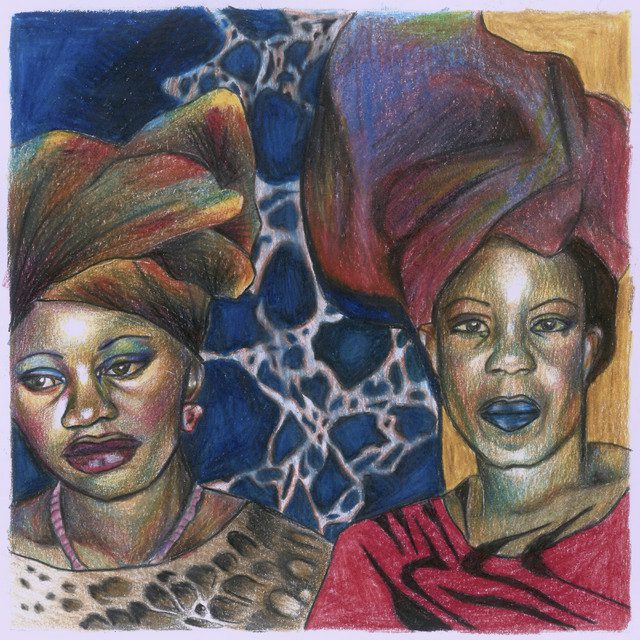

21. Sudan Archives: The BPM

The BPM’s prominent Afrofuturistic concept evokes the chrome-plated sci-fi aesthetic of Janelle Monáe’s Dirty Computer as well as the cavernous, neon-lit sensuality of Kelela’s Raven, but its hypnotic, rave-like energy and avant-garde impulses place it in a league entirely of its own. The album is an attempt at showing how liberating it can be when technology is used as a form of self-expression. The BPM’s loose structure might seem like it could stifle such an aim. There’s certainly a version of this record that prioritizes momentum over feeling, where every track slides into the next à la Beyoncé’s RENAISSANCE. However, Brittney Parks makes it clear that every song deserves to exist as its own little universe, or in keeping with the club metaphor, its own little room to dance in. If you want to get lost in the rhythm with a sexy stranger, you can enter “THE NATURE OF LOVE,” “A COMPUTER LOVE,” or “MY TYPE.” If you’re in your feels and need to vibe out the blues, you can wander into “DAVID & GOLIATH” or the gentle closer “HEAVEN KNOWS.” In inhabiting “Gadget Girl,” Parks reckons with the painful, often isolating experience of being a self-sufficient human while searching for a release from all the external pressures that come with it in the safe, freeing space of the club. These layers suffuse The BPM with palpable emotion and dynamism, frequently beguiling in straddling the line between meditative and boisterous. Parks does a remarkable job finding the fun in her introspection in a way that feels organic rather than forced. As a whole, The BPM feels designed for anyone seeking catharsis and solace in a world better than our own, one that vibrates with pleasure and is made for the people by the people. It’s unlikely we’ll get that world in our own, but in the meantime, Sudan Archives provides one that we can hopefully look forward to one day. —Sam Rosenberg [Stones Throw]

20. Hayley Williams: Ego Death At A Bachelorette Party

Ego Death At A Bachelorette Party is undoubtedly Hayley Williams’ best offering of solo music yet, and there’s an argument to be made that it’s among her most impressive music period. What the title suggests and what the music provides are dueling objectives: Williams is confident and unglued, producing songs that rival the marquee parts of Riot! and After Laughter. What she sings in “Negative Self Talk” is true: “I write like a volcano.” This is not the work of the woman who leads Paramore, but a reminder that Williams’ talents are broader and far more contrasting than Paramore’s safest conventions. Ego Death, in all of its boundary-nudging, alt-pop glory, sounds like a reset for a musician who has long deserved it—because let’s not forget that, in 2003, Williams signed to Atlantic Records as a solo artist at the age of 14. The label wanted to make her a pop singer, but she wanted to be in a band. 22 years later, Williams is free, naming her own label “Post Atlantic.” She even cuts right to the chase about the contract baggage on “Ice In My OJ,” screaming “I’m in a band! I’m in a band!” until the blister erupts. The tracklist is a grab-bag of enjoyment, but the miscellany is never reduced to randomness, only a curation of strengths. —Matt Mitchell [Post-Atlantic]

19. Joanne Robertson: Blurrr

On Blurrr, her second solo outing for AD93 and sixth album overall, Joanne Robertson’s solo songs emerge as cloudy exercises in emotional record-keeping, smoothed and sweetened by Oliver Coates’ wondrous strings. It’s a haunting collection of delicate songs with an overall smoothness and occasional flashes of discord that make them truly unforgettable. Blurrr opens with “Ghost,” where Robertson’s guitar rumbles with each gentle strum, coating the song with a sense of doom not unlike Dragging a Dead Deer Up a Hill-era Grouper, but with more entropy. She croons, “Through time you stand still,” carefully but unflinchingly directing her voice toward the heavens while her instrument languishes beneath her. Her bellowing strums give way to a deep, intricate melody on “Why Me,” whose figurative lyrics converge into one striking image of embodied connection and nourishment: “At least I’ll be lyin’ down here / Waitin’ for the rain / Waitin’ for your hands / To kindly take mine / Again.” She sings with composure, but little imperfections give the song a charming, humanistic quality. “Friendly” is even brighter. The foundational guitar loop feels grounding for what is ultimately a sunny seven-minute-long saunter with no immediate destination or catalyst. —Devon Chodzin [AD93]

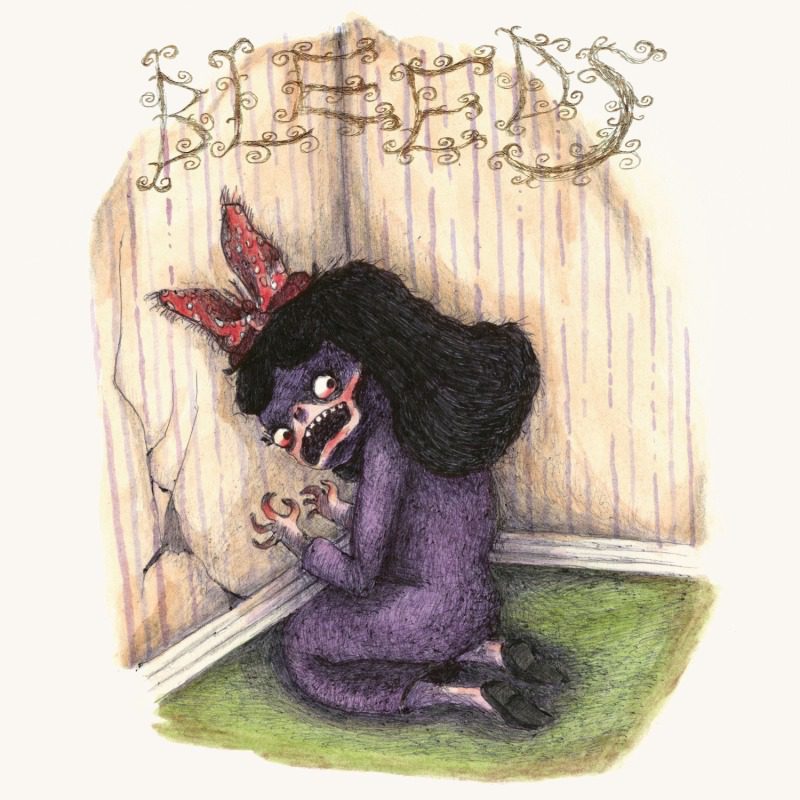

18. Wednesday: Bleeds

On Bleeds, darkness and humor uplift each other, with Karly Hartzman’s pen amplifying them both. There’s the narrator on “Townies” whose nudes get shared without her consent by a now-dead high school ex; the pitbull puppy “pissin’ off a balcony” in “Wound Up Here (by Holdin On);” the band’s multi-instrumentalist Xandy Chelmis vomiting in a Death Grips pit on “Pick Up That Knife.” The tragicomic takes a leading role on the band’s sixth album, which showcases its core songwriter sharpening her keen sensibilities as a preternaturally gifted raconteur. With more eyes and ears on Wednesday than ever, they don’t reinvent themselves for further mass appeal. Instead, Bleeds sees them truck ahead to refine their proven prowess. When Wednesday captured the world’s attention with 2023’s Rat Saw God, it marked the kind of breakthrough that turned them from an underground staple into indie rock luminaries. Suddenly, Hartzman became the voice of a generation, not long before the band’s lead guitarist (and Hartzman’s ex-partner) Jake “MJ” Lenderman achieved a similar feat with last year’s Manning Fireworks. But whereas Lenderman almost exclusively leaned into Wednesday’s twangier stylings, Hartzman has doubled down on Sonic Youthian squalor while still injecting her fair share of country-fried zest. —Grant Sharples [Dead Oceans]

Read: “Wednesday rejoice in their sicko acrobatics”

17. ROSALÍA: LUX

ROSALÍA’s fourth album continues her trend of constant artistic transformation. Rife with strings as stormy as Vivaldi’s and vocal performances as dramatic as Carl Orff’s cantatas, the ambitious avant-pop work on LUX could be categorized as “classical” above all else. Yet, in the lineage of artists such as Kate Bush, FKA twigs, and Björk—who features on the track “BERGHAIN” and can be seen as a patron saint for this type of pop experimentation—ROSALÍA appears uninterested in these cumbersome musical boundaries, soaring instead towards a far more elusive, fearless vision of what pop can be. Yes, she’s working with the London Symphony Orchestra, but she’s also calling on producers like Noah Goldstein and Dylan Wiggins. Divided across four movements and sung in 13 different languages, LUX is an explosive, experimental album that demands a lot from its listeners, but not without offering resplendent gifts of beauty, drama, and grace. LUX’s themes float around love, God, faith, and the divine feminine, and the album’s cover—ROSALÍA in a skin-tight habit, eyes closed in sensuous devotion, hitting that Sade Love Deluxe pose—should give good indication of its preoccupation with what is both bodily and holy. During the lead-up, ROSALÍA devoured the works of cult feminist writers including Simone Weil, Clarice Lispector, and Chris Kraus. Much like these women, ROSALÍA is concerned with questions of the mystical and the erotic, and here in LUX, desire—despite all its chaos and brutalities—is undeniably divine. —Lydia Wei [Columbia]

16. Cameron Winter: Heavy Metal

Heavy Metal possesses limitless concepts, stories, journeys, and fables rolled into one. “Nausicaä (Love Will Be Revealed)” is profound and somewhat prophetic, as Cameron Winter voices his need to see and be seen, to hear and be heard, to know that someone is here and for someone to know that he is here. In Homer’s Odyssey, Nausicaä is young and beautiful, and helps Odysseus after he is shipwrecked by offering him clothes and bringing him back to the edge of town. The songs of Heavy Metal ache with a deep sense of longing, and a hope that help will come in the form of love—which takes many different shapes throughout. Love will be revealed, it “takes miles,” but it will eventually call—and when it does come, it will be like nothing you’ve ever felt before. “There’s a sardonic self-awareness that defines Heavy Metal and its existentialism, but the illusive presence of God and religion throughout the album blurs the line between handcrafted irony and pure authenticity. References to deity reveal themselves, such as when he tells his lover they were born to hold his “cannonball brain like the Lord holds the moon” on “Try As I May.” The most damning display of this is the feverish descent of “$0,” in which Winter triumphantly proclaims, “God is real, I’m not kidding this time, I think God is actually for real, I wouldn’t joke about this.” For how straightforward his claims of enlightenment are, his detached, impassive tone still makes it hard to tell if he truly is for real or not (he swears he is). It shouldn’t be funny, but in a feat that is nothing less than impressive, it still manages to be. But it feels as though that was one of Winter’s goals with the work—to create a paradigm of truth and fiction, reality and the abstract, humor and utter seriousness. —Alli Dempsey [Partisan]

15. Florry: Sounds Like…

Sounds Like… is as grand an upgrade that any ruckus-throwing batch of troublemakers like Florry could make. The sludgy accoutrements of “Waiting Around to Provide”—which hocks a phrase from Townes Van Zandt—wink into a big country stomp, with Jackson Browne’s melodicism splattered atop the humid parables of Drive-By Truckers. Harmonica puffs tattoo the air, while an organ hums like a guitar chord. “Say Your Prayers Rock” would have nestled in with the sensual and staggering looseness of the Rolling Stones‘ Exile on Main St.’s third side. Van Zandt swings back into view on “Dip Myself In Like An Ice Cream Cone,” as Francie Medosch turns into a gas station poet serenaded by a wah-wah talk box rippling like a bassline. But don’t mistake Sounds Like… for some phony imitation game. This music—part hangout chatter, part guitar solo rummage sale—is a persistent, euphoric choogle. The door-kicking riffs and road-worn fables come free of charge. “Hey Baby” finds Florry’s full-band sound growing ten-fold, with Medosch’s influences of the Jackass theme song and country-fried Minutemen serving as a raw-hemmed, honking template for her and her crew. “First it was a movie, then it was a book” is a sentence-case dream of rollicking gravitas. Medosch and Murray’s guitars collide into each other, stretching two-ton riffs around organ, pedal steel, and homespun, jammy crescendos. Sounds Like… ends in “You Don’t Know,” a skyscraper song flirting with the 8-minute mark. It’s a doozy, waltzing into view like a scorned lover with a tail caught between their legs. Medosch stresses every syllable, coiling her accent around every vowel. —Matt Mitchell [Dear Life]

14. billy woods: GOLLIWOG

Psychodrama is nothing new to a Brooklynite whose decades-long career is defined by records steeped in anxious atmospherics, but rarely has that dread sounded so acute. GOLLIWOG’s myriad producers, many of whom are previous contributors to billy woods’ catalogue, color-grade the MC’s murky tableaus. Sometimes, they fabricate the entire set. On “STAR87,” Conductor Williams pairs tinny boom-bap with quivering violins, errant bass, and the unceasing ring of landlines. (“They wanna know where the bodies is hid,” woods’ narrator reveals eventually, as if it would ever help.) woods opens “Waterproof Mascara” with a portrait of a weeping mother before shifting subject but Preservation keeps that weeping in the foreground, looping incessantly like a dark splinter lodged in the heart. The crackle of a palpitating digital heartbeat thrums underneath al.divino’s introductory verse on “Maquiladoras” until the first gunshot is fired, after which a heartbreaking piano chord punctuates the demarcated timeline. In lesser hands, GOLLIWOG might read too overwhelming or leaden to be enjoyable, but in the same vein as 2023’s patchwork Maps, woods makes plenty of room for crucial doses of levity. Modern existential nightmares receive an absurdity apropos to their context (“Uncanny valley AI hit him with the hesi screaming ‘Carrie,’” cracks woods on “Corinthians”); dream and nightmare logic allows for a surprise punchline (“I time-traveled and still picked Darko Miličić,” on “Cold Sweat”); the twisted, MF DOOM-honoring “Misery” is a lascivious, evocative outlier; dark comedy naturally abounds on a particularly gutting anecdote in “Lead Paint Test” (“Father put her out her misery on the kitchen floor / Mom said, ‘Be proud of her, she made it home’”). It’s woods being woods. Even when the subject is heavy, his pen can’t help but carve a devilish grin. —Rob Moura [Backwoodz Studios]

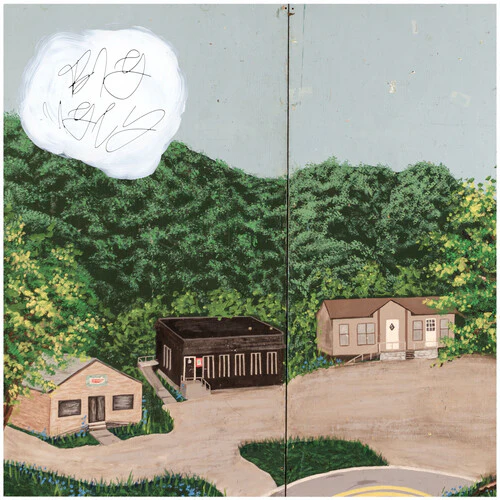

13. Fust: Big Ugly

Bookended by collapse, Big Ugly is a mausoleum for small Southern bygones, wrought in close detail by Aaron Dowdy: torn-down small towns where heaven seemed in-reach, a beer-fisted past self with nothing else to hold, the cans and cigarettes that lined a shabby old convenience store’s shelves. In answering questions of Southern living, it raises an age-old, universal query: What does it mean to love people and places once they’ve become part of history, one that hasn’t quite passed? The album’s title derives from a West Virginian area based around a Guyandotte River tributary named for the crooked, “Big Ugly” creek rushing through it. A hastily assembled Internet guide to Appalachian West Virginian communities introduces Big Ugly as “one of those place names newspaper columnists grab on a slow day,” but Dowdy saw more than a conspicuous headline in the nickname—the evocative, oddly affectionate word pairing captured the essence of the songs he’d been writing: unfiltered snapshots of hardscrabble Southern living zoomed in on the people and places. Fleshed out by a full band and esteemed guest players, Dowdy’s final compositions are, indeed, big. They aren’t always pretty, per se (although exquisite fiddle pulls and glossy keys attenuate some of the denser offerings, to an unearthly, beautiful effect), but unabated love seeps from every cranny of even the gnarliest, craggiest constructions, deluging every corner of the heart. Each song is a microcosm of its own, and the anecdotes within each, if banal, are so intensely vivid that it’s challenging to imagine them having solely transpired on paper—you can almost trace the steps of every character, deepening their footprints as you meander the dirt roads winding across 11 chapters. —Anna Pichler [Dear Life]

Read: “Fust: The Best of What’s Next”

12. aya: hexed!

There is never a stagnant moment on hexed!. Across ten dizzying tracks, aya emphasizes music’s malleability in myriad forms. hexed! throws unwary listeners into its vertiginous world in media res. Synthesizers vaporize and marble and liquify, as if being sculpted from raw materials in real time. Tempos shift without warning. Stray sonic ephemera enters the mix as quickly as it leaves. aya forces us to witness a grotesque metamorphosis, prying our eyes open and never allowing us to avert our gaze from the gristle. She’s here to ensure we have the best bad time imaginable. Even though hexed! hews to pop conventions more than its predecessor, the droney, soundscape-heavy im hole, aya’s methodology (and the ensuing result) is still heady and singular. The reason her production sounds so tangible this time around is because of her adoption of physical modeling synthesis, in which a synthesizer is modeled after an instrument like a guitar or piano, and the performer can modulate aspects such as string tension, vibrations, and other physical characteristics. “It’s a far more physical relationship that you have with tone-shaping,” she told Pitchfork earlier this year. When she was creating this record, she was “designing all of the instruments, which are real and yet not real.” It’s a style of synthesis commonly found in SOPHIE’s work, but where her music contains a rubbery, plasticized effect, hexed! sounds as if it were recorded at a construction site and molded into anti-club jams. It sounds like the craft of an experienced alchemist. —Grant Sharples [Hyperdub]

11. Youth Lagoon: Rarely Do I Dream

The experience of Youth Lagoon’s latest album, Rarely Do I Dream, embraces sentimentality and memory, but the project is not gobsmacked by melancholy. Rather, it’s a collection of music filled with kind self-reflection and hopeful imagination, as Trevor Powers approaches the totality of life through small, digitized and grainy moments, showcasing and scattering them across irresistible melodies and buttery piano leads propelled by infectious drumming. The field recordings of him and his family, including his brother Bobby, become a compositional element and ground the surreal character portrayals in vibrant snapshots of childhood, forming the foundation for Powers to, once again, reinvent Youth Lagoon. Above the found audio lies Powers’ most sonically diverse album to date, injecting the smooth atmosphere of 2023’s Heaven Is a Junkyard with fuzzy synthesizers, reverb-drenched guitar leads and infinitely groovy basslines. Heaven Is a Junkyard was a fresh return to Youth Lagoon after Powers had abandoned the project, replacing lo-fi bedroom pop with crystal clear percussion—drums, bass and serene piano layers floating atop every song. It’s a wonderful listen that lives forever in its pillowy atmosphere, whereas Rarely Do I Dream changes channels almost every song, flipping a switch to a new scene. —David Feigelson [Fat Possum]

Read: “Youth Lagoon opens the portal”

10. McKinley Dixon: Magic, Alive!

Magic, Alive! is McKinley Dixon’s fifth album, and it’s also the biggest risk he’s taken yet—a collection of tracks always flirting with overproduction and clutter. The music is brimming with orchestration; it’s not “everything but the kitchen sink,” but “everything and the kitchen table.” Dixon isn’t afraid to add more voices and hands into his musical soup, and each song is an elixir of jazz-rap, with pockets layered in chain-link grandeur. Every chapter of Magic, Alive! is bigger than him, yet his verses focus on the micro with historical hip-hop citations, literary allusions, and horror films metabolized into heady sonic palettes. Like the illustrations he animates in his spare time, the rarely-pedantic Dixon meticulously sketches expressions of people he both knows and imagines. His lyrical fascinations with mythology are decorated in rare and endangered fits of orchestral patterns; the noisy percussion, mechanical poetry, and blood-boiling strings haunt the magic Dixon is chasing in the epilogue of Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!?’s block-bending cynicism but never smear it. As he raps on “Listen Gentle”: “It’s tragic, trying to keep my kindness in my steps with lightning in my eyes.” Dixon sinks his teeth into the Magic, Alive! story on “We’re Outside, Rejoice!,” as he summons a concrete pastoral again but doesn’t wear out its meaning. There are far too many front doors still unopened on his turf to stop painting the neighborhood just yet. A tint of blue washes over the brotherhood at the song’s core: “I love laying with you here in the grass, feels like it was just us in the worlds that passed.” Dixon speaks in Toni Morrison titles while seeking redemption and clinging to memories the bodies around him have sung into life. “My face inhales the sun, grab your hand with no plan then we run!” Magic, Alive! is a conceptual, allegorical achievement—a story of three young kids whose friend passes away, the monuments they build in his memory, and the lives they’d kill themselves to restore. —Matt Mitchell [City Slang]

9. Horsegirl: Phonetics On and On

One of the greatest feats of songwriting—of any writing, really—is arranging words into combinations that no one else has ever constructed before. Contrarily, there’s also a challenge in taking a phrase or expression that’s been echoed a million times, and using it in a way that forces the audience to really think about these familiar words. The latter is where a record like Phonetics On and On, the sophomore effort from formerly-Chicago-now-New-York-based rock band Horsegirl, thrives. As its title suggests, Phonetics is a record closely concerned with the shape and texture of each sound. The rumble of Gigi Reece’s drums ushers in the call-and-response hook of opener “Where’d You Go,” before the song spins out into a wiry, “Heroin”-reminiscent guitar outro, while more downtempo tracks like “Rock City” and “Julie” recall the eerie simmer of The Velvet Underground & Nico’s most haunting slow-marches. Similarly to the Velvet Underground’s ever-influential debut, the Cate Le Bon-produced Phonetics has an affinity for stretching the distance between instruments and hypnotically fixating on a single musical element (akin to the punishing sheen of the guitar chords on “Venus In Furs,” or the dirgelike chimes parading through “All Tomorrow’s Parties”). Closer “I Can’t Stand To See You” is Horsegirl’s “After Hours,” a mellow singalong that begins with Nora Cheng extending an invitation: “Do you want to go home now? / The night’s almost through / Let’s sit on the floor now / And talk, me and you.” A copy of Lou Reed’s classic solo album Transformer lurks in the background of the “Switch Over” music video as a piece of blink-and-you-miss-it set dressing. So many of Phonetics’ song structures revolve around taking something that is, at face value, simple or unremarkable, and repeating it until all association has been wrung out. It’s the same effect as flipping a lightswitch on and off, opening and closing the same door over and over again, or getting a single word or phrase so stuck in your head that a few minutes of letting it float around in there turns it to gibberish. —Grace Robins-Somerville [Matador]

Read: “The in-betweens of Horsegirl”

8. Rochelle Jordan: Through the Wall

Big hair, mirrorballs, and decorated necklines abound on Through the Wall. Rochelle Jordan isn’t afraid “to take up space” in her masterpiece—a luxurious, Chicago and Detroit house-inspired saga replete with desire, velvet, bouncy beats, and moody pretense. Produced by KLSH, Jimmy Edgar, Kaytranada, Initial Talk, DāM FunK, and Terry Hunter, Though the Wall is 17 songs long but never drags, and not many contemporary, 60-minute records are as consistent or polished. Cool hooks get woven into boots-n-cats rhythms, while the spanning grooves are pocketed and tactile. Through the Wall belongs in the conversation of greatest contemporary dance music releases, alongside Dawn Richard’s Second Line, Kelela’s Raven, and Beyoncé’s Renaissance. The songs communicate with Black exemplars from then and now, like Janet, Diana, Chaka, and Sade, and Jordan aims for the “boldness, the bigness, the enchantment” of songs like the Spice Girls’ “Say You’ll Be There” or Mariah Carey’s “Fantasy.” You can hear those motivations in the album’s addictive, acrobatic DNA, in the Brandy-summoning “Sweet Sensation,” the bouncing, provocative “Crave,” and the serpentine, four-on-the-floor “Sum.” “Get It Off” sounds like an aughts pop record, while “The Boy” is this plush, feral synth hit that exists not in the post-R&B or electronic tracts, but in a campy, escapist pantheon of its own. The colors streak and the repetition tastes so good you don’t even realize the party ended hours ago. —Matt Mitchell [Empire]

Read: “Rochelle Jordan earned her bragging rights”

7. Ryan Davis & The Roadhouse Band: New Threats From the Soul

As a survey of the state love leaves us in, New Threats From the Soul is unflinching; in lieu of spewing vague sentiments, Ryan Davis channels loss into precise, tangible imagery. On the desperate and borderline creepy vignette “Monte Carlo / No Limits”—a sort of spiritual successor to the Replacements’ equally desperate, not-so-creepy dirge “Answering Machine”—a non-functioning doorbell delivers a crushing blow to the narrator’s efforts towards reunion with an ex (it “doesn’t work, but it don’t need to if there’s no one at home”). Mundane tragedies, like “daffodils dyin’ in a theme park pint glass,” take the foreground, while the celestial and conceptual are defanged, distorted into bit parts and props: the moon’s face is scarred with acne; life is cast as a blundering, game-show host type; time is neither friend nor foe, “more like one of the guys from work.” New Threats From the Soul is jam-packed with arresting turns of phrase, but never flounders under their weight—each witticism feels earned and essential rather than shoehorned or self-indulgent. Every line contributes to an exhaustive document of how extensively heartache blurs our lenses—how we find it everywhere, in everything. How it finds us. —Anna Pichler [Sophomore Lounge]

Read: “The phantoms of Ryan Davis”

6. Oklou: choke enough

It feels like Oklou makes pop music for the kids who played through Bach’s The Art of Fugue. Having grown up classically trained in France, Marylou Mayniel’s output at the end of the 2010s reveled in the peculiarities of closely held melodies and harmonies, and she emerged as the eternally understated figure of the NUXXE world. With choke enough, Mayniel’s precise rhythms and dynamic shifts give what sounds at first like bite-sized electro-pop into an exquisite tapestry of classical precision and pop swagger. The digital clarinet on “obvious” is weird and beguiling; the negative spaces between her flute and keys on “thank you for recording” make the song feel as light as a snowflake. choke enough is full of charm and care that make every song feel like a miniature world to explore. —Devon Chodzin [True Panther]

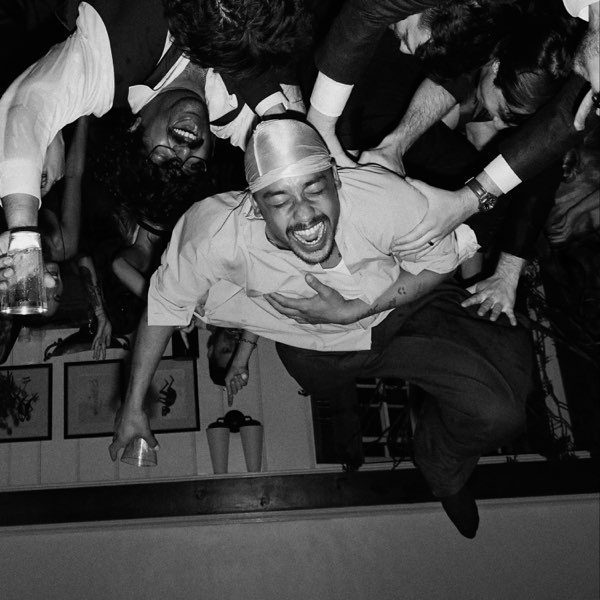

5. Dijon: Baby

Dijon can kind of fly: endlessly skipping and swaying in a controlled mania—endearingly stumbling cause he’s moving so fast his feet can’t keep up. His second record, Baby, was first teased with a demo evoking Lowell or Levon riffing in rehearsal, titled “BABY_barn+burner!!” And “barnburner” feels apt, because Baby is a house on fire: a homemade rocket ship running on love and “lust degrees,” stroked with a unique smirk and swagger as Dijon takes off through the atmosphere, breaking the sound barrier. The planet can’t keep him down: vocals peak and rip like sparks hitting gas, crack with a whip-like snap, or undulate like a satin sheet rippling. Even so, you can’t escape gravity’s pull when you’re ascending at this velocity, and memory and mind try to slow him on “my man” and “loyal & marie.” But the heart prevails, as he recovers those invisible tracks to his lover on “Automatic,” and pushes in all his chips, going all-in on “Kindalove.” Buckle up, cause you and I might just jump out of our seats if we surrender to the frenetic trance that is Baby. —Andrew Ha [R&R/Warner]

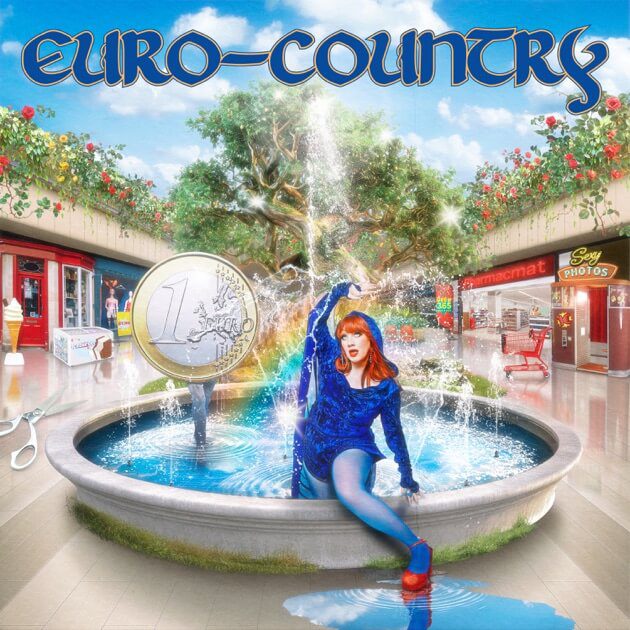

4. CMAT: EURO-COUNTRY

When I, in the middle of a sold-out CMAT headline show, proclaimed to my friend that the Irish singer-songwriter was “my Taylor Swift,” I’m not sure that I knew what I meant the very moment I said it. Yet, the more time I’ve spent with the artist also known as Ciara Mary-Alice Thompson’s third studio album EURO-COUNTRY, the more I’ve clung to the statement’s truth: in these songs, there is a frequently photorealistic depiction of me and my friends’ lives. It rings out in the civic adoration and fear for a hometown in the title track, in the scathing wink at your own figure in the mirror in “Take a Sexy Picture of Me,” and in the pleading cabaret sway of “Janis Joplining.” It certainly doesn’t hurt that each track magnifies those montages of life with the help of the catchiest melodies you’ve heard this year couched in country-pop arrangements and, perhaps most key, an irrepressible sense of humor. “This is making no sense to the average listener,” CMAT worries to herself on the stadium-sized haters’ rant of “The Jamie Oliver Petrol Station,” but she needn’t worry, as even her smallest grievances grab tightly to the faintest pains within each of us and refuse to let go. —Elise Soutar

3. Geese: Getting Killed

Listening to Geese’s last album, 3D Country, now is akin to watching someone laugh while all of their limbs get twisted backwards, as guitars throb like an empty tooth socket and percussion clatters until your back straightens. I grew up listening to ball-busting, face-melting rock and roll—the kind of music I thought needed saved by an album like 3D Country. If Getting Killed is out to prove anything at all, it’s that rock and roll doesn’t need saving. Rock and roll needs playing, and, by God, Geese do exactly that. In its loose fervor, Cameron Winter, Emily Green, Dominic DiGesu, and Max Bassin marry fire-branded Hollywood sleaze with craggy, top-lined jazz-rock and bellyaching, twisted tempos nearly gone to the dogs. Winter’s lyricism—at times oblique, at times sincere, and at times campy—commands your attention, too. A hilarious bickering on “Half Real” (“You may say that our love was only half real / But that’s only half true”) reveals a shadowy contemplation on “Bow Down” (“I was a sailor / I was a sailor and now I’m a boat / I was a car / I was a car and now I’m the road”); there’s humor in the turmoil on “Getting Killed” (“Yeah I am getting up to leave / Yeah I am taking off my pants / I’m getting out of this gumball machine”) and there is defiance in “Taxes” (“If you want me to pay my taxes / You’d better come over with a crucifix / You’re gonna have to nail me down”). And Winter’s bandmates convene with the haints of rock and roll bedlam, capricious in their tangents through folky lullabies (“Au Pays du Cocaine”), dainty, strummy ooze (“Cobra”), metallic skronks (“100 Horses”), skittering, barrelhouse backdrops (“Islands of Men”), stomping, controlled burns (“Husbands”), and stormy, percussive carnage (“Long Island City Here I Come”). —Matt Mitchell [Partisan]

2. Los Thuthanaka: Los Thuthanaka