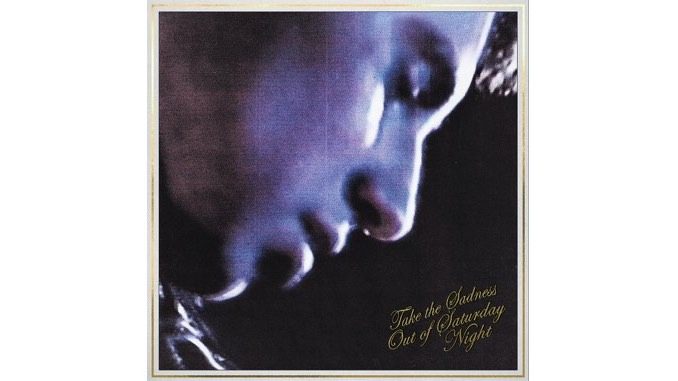

The last two years have been good to Jack Antonoff. After producing acclaimed records for The Chicks, Taylor Swift and Lana Del Rey, Antonoff was rewarded with two consecutive Grammy nominations for Non-Classical Producer of the Year. He followed that up by producing a handful of tracks on Olivia Rodrigo’s Sour and will cap it off by producing Lorde’s Solar Power. The former fun. guitarist has had no trouble stepping into the creative visions of every artist he collaborates with, but on Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night, Antonoff struggles to step into his own artistry. At best, the record is an average collection of pop songs with a few bangers that’ll surely nuzzle themselves into curated genre playlists on Spotify, or find homes in the thick of lost dive bar background noise, for years to come. But Sadness is recycled hogwash down to its core. Antonoff’s last record, Gone Now, was a love letter to his Beatles-centric influences, and was done well enough to initially position him far ahead of his former bandmates. On this new project, though, Antonoff takes a few steps back, clearly wanting to be anyone but himself.

Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night is what happens when prep school kids discover Bruce Springsteen’s opinion of the abandoned steel plant across town for the first time. When “Chinatown” rolls in, featuring a guest verse and backing vocals from The Boss himself, it’s an immediate, floundering mess. Antonoff splays his oddly muted, Dirty Beaches-like vocals over a Destroyer-esque instrumental. He does to Springsteen what Kanye West and Rihanna did to Paul McCartney on “FourFiveSeconds”: He’s more a name on the tracklist than a vital piece of the song’s puzzle, more a co-signer of Antonoff’s retro ambitions than a breath of fresh air. “Big Life” is Born in the U.S.A. fused with Stray Cats and yelping wah-hoos, topped off by nasal, piercing arrangements and passionless bravado.

The tonal, crescendoing shifts Antonoff so beautifully put to wax on Gone Now cuts like “I’m Ready To Move On/Mickey Mantle Reprise” are rehashed on Sadness, but abysmally. The eccentric, bubbling brass from the last record return under the guise of textbook, recycled pop. The saxophone duetting with an electric guitar during the breakdown on “How Dare You Want More” is fun, but doesn’t absolve the song of being a carbon copy of its modern hippie-rock predecessors: The track’s opening psychedelic riffs have the same dry, sun-baked tinge as Ezra Koenig’s on “This Life” by Vampire Weekend. Sadness comes off as a covers album long before it musters up any courage to pose as a half-baked follow-up to an earnest sophomore release—so it’s a loyally consistent ripoff when the chord progression and Antonoff’s vocal cadence on “45” are both damn near identical to Evan Stephens Hall’s performance on Pinegrove’s “Phase.”

The album’s centerpiece is “Stop Making This Hurt,” Antonoff’s most ambitious, original instrumental on the record—yet the grandiose orchestra of sensual saxophones, confident guitars and lush pianos struggles to give the off-putting lyricism a pass. When Antonoff commits a faux pas of lazy social commentary by singing, “The kids are on the street and / they’re cryin’, ‘Let me live in my country’,” he densely follows it up by pivoting into a line about him and a buddy heading into the night with nothing but a car and a dream. Not even Springsteen would drink in such a cliché convolution, where the juxtaposition of two lines turns problematic, trivializing the street kids’ struggles to the point of rhetorical violence.

Sadness is the perfect album for anyone like Antonoff: Someone who barely lived through the ‘80s but knows the buzzwords of the era, and, like Springsteen, grew up watching the Big Apple’s glamour from across the Hudson River. But Springsteen has always known exactly who he is, and Antonoff weaves in and out of different lifted poses as if he doesn’t know which mask fits him best. The multi-instrumentalist has never been this chameleonic. He’s never needed Nate Reuss’ glass-cracking tenor this much, either. Sadness is mediocrity promoted as homage, showing itself as hastily thrown-together soundcheck warm-up fusion. But Antonoff is so meticulous with his production habits that there’s no doubt he spent a great deal of time putting this record together. That’s what’s so damn head-scratching—how, despite his mass-desirability behind the boards and the critical legacy he’s still forging, he’s managed to nosedive this far into banality. Jack Antonoff so desperately wants to be Bruce Springsteen. But on Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night, he’s barely even John Mellencamp.

Matt Mitchell is a writer living in Columbus, Ohio. His writing can be found now, or soon, in Pitchfork, Bandcamp, Paste, LitHub and elsewhere. Find him on Twitter @matt_mitchell48.