Long before she ever had the chance to open for Frightened Rabbit, was asked to collaborate on a song with the band or performed at lead singer Scott Hutchison’s memorial concert in New York after his death in 2018, Julien Baker was a massive fan of the Scottish indie outfit. And it all started by accident, too: Baker and her friends went to see The National at the Ryman in 2013, going in blind to Scott Hutchison and co.’s opening set.

“I saw them do ‘Acts of Man’ live and I lost it,” she told me in a 2018 Village Voice interview ahead of that band’s 10-year anniversary tour of The Midnight Organ Fight. “I just was floored by their music. I went out and bought Pedestrian Verse and listened to it nonstop for like six months. It’s so beautiful!”

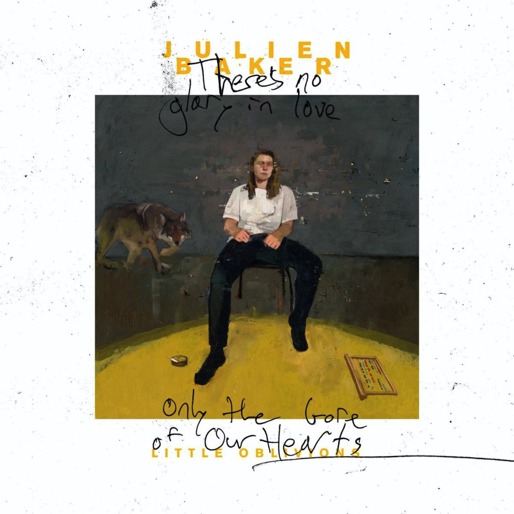

Seven-plus years after that fateful concert, Baker is releasing Little Oblivions, her third record to date and first album with complete instrumentation. It’s about as close to a modern iteration of “Dylan goes electric’’ as we’re likely to get these days: 2015’s Sprained Ankle and 2017’s Turn Out the Lights eschewed drums and bass for delicate acoustic and electric guitar soundscapes—with the occasional piano—to create the most intimate of listening experiences, records that felt like you were having your feelings sung back to you after your worst day at high school, alone in your childhood bedroom.

But now, Baker is aiming for the rafters, using Frightened Rabbit’s sneakily best album as a guide. Her music always had a very large helping of emotional catharsis, but this time, her screams are backed by swelling instrumentation, crashing guitars and, when concerts are allowed to return, *gulp* a full band (though she did play every instrument on the record herself).

Little Oblivions is Julien Baker’s Pedestrian Verse. And that is absolutely a great thing.

You can hear it when album opener “Hardline,” perhaps Baker’s best song to date, explodes into a fist-in-the-air call-to-arms a la the aforementioned “Acts of Man,” a track that will undoubtedly make new fans lose it in the very same way Baker did when she first heard Frightened Rabbit perform it live in 2013. The outro of “Bloodshot,” propelled by Baker’s pulverizing drumming that recalls that of Frightened Rabbit drummer Grant Hutchison, feels like it’s building up to the same epic guitar solo as the Scottish band’s “The Woodpile.” You can practically hear the late Hutchison’s Scottish brogue sing Baker’s “I don’t need a savior, I need you to take me home / I don’t need your help, I need you to leave me alone / I’m out where the drunks at the bar talk over the band / I try express I can’t understand, I beat at the keys, I bloody my hands till you hear me” on “Relative Fiction.”

But Little Oblivions is much more than mere cosplay. Far from it—Baker takes lessons from the band that she said “informed much of my songwriting and my poetic sensibilities by admiring their lyrics and their songcraft,” and turns it into her own, giving these songs a more sensitive and dramatic instrumental touch, and an emotional weight that rivals her starkest compositions.

Take “Crying Wolf,” a sordid solo keyboard ballad, for instance. On its face, it feels like something that’d fit nicely on Turn Out the Lights, nudged between piano-led mid-album cuts “Televangelist” and “Everything That Helps You Sleep.” It keeps a similar song structure to those tracks, too: a slow, quiet solo piano introduction that eventually gives way to a cathartic climax marked by Baker’s rising voice that turns into one of her trademark pseudo-screams.

But “Crying Wolf” showcases her newfound instrumental and production sensibilities, as well. Where the track would have been more straightforward on Turn Out the Lights, “Crying Wolf” combines warmer synths comparable to Bon Iver’s “Beth/Rest” with a gorgeous guitar solo and angelic backing vocals, sending her voice skyward. It’s also the track that holds Little Oblivions together, bridging the gap between the record’s midtempo, lusher arrangements, and acting as a reminder of how direct and intimate her quieter songwriting can be (later album cuts “Song in E” and “Ziptie” are equally beautiful).

And it seems as if Baker knew this as well, adding the titular wolf to the impressionistic album art, circling around her as she sits in a dreary, gray room, almost dark enough for the wolf to sneak up behind her, unseen. The wolf imagery here brings up an interesting contrast with Radiohead’s “Wolf at the Door,” when, on the Hail to the Thief album closer, Thom Yorke mutters, “I keep the wolf from the door but he calls me up / Calls me on the phone / Tells me all the ways that he’s gonna mess me up.” But on “Crying Wolf,” Baker gives in to the beast, seeking it out in a melancholic sense and deciding not to put up a fight despite wanting to be anywhere else: “I’m not crying wolf, I’m out here looking for them / In the morning when I wake up naked in their den / I’ll swear off all the things I thought that got me here / And in the evening I’ll come back again.” As always, it’s Baker’s most relatable lyrics that are the most devastating.

After two records of Baker’s stunning vocal crescendos lifted up by next to nothing other than her voice, it’s thrilling to finally hear what happens when she’s backed by instrumentals that share her vocal intensity. It’s goosebump-inducing, yet in a wildly different way than before. While her “God, I wanna gooooo home!” from Sprained Ankle’s “Go Home” or “I take it all back, changed my mind / I wanted to stayyyyy” from Turn Out the Lights’ “Claws in Your Back” were crushing in their stark isolation, backed only by funereal piano or delicate, swirling strings, respectively, louder, more complete instrumentation takes her voice to new heights. “You say it’s not so cut and dry, it isn’t black and white / What if it’s all black, baby, all the tiiiiime” from “Hardline” sets the stage for the rest of Little Oblivions with a show-stopping, jaw-dropping, “holy fuck”-inducing moment on track one, the first of many throughout. Hell, even her “Now I’m stuck inside a vision that repeats, repeats, repeats … ” refrain on “Repeat” offers perhaps the first danceable moment of her whole career, adding upbeat drums that just beg for a remix (something I never thought I’d write about a Julien Baker song).

But like in her past work, it’s the barely noticeable, throwaway moments that make Baker’s impossibly personal records feel even more human. The little voice crack on the word “breaks” (“I can see where this is going, but I can’t find the breaks”) on “Hardline.” That killer sigh on “Faith Healer” before the synths kick in. The too-early drum beat on “Ringside” as she sings, “So you could either watch me drown / Or try to save me while I drag you down.”

These moments have been there from the beginning, starting with her singing “lift my voice” on Sprained Ankle’s “Rejoice” as her own voice gives out. “It feels like you’re in the living room with [the artist] and they screwed up a little, and they left it because it’s real,” she once told me for SF Weekly.

Even with booming guitars, pounding drums and soaring instrumentals, Little Oblivions feels just as intimate as Baker’s more, well, intimate albums. It’s an impossible task to make a massive capital-R Rock album sound just as home in an arena as it would in a living room, but somehow, some way, Baker has managed to crack the code.

On “Ringside”—a track whose bouncy midtempo chugging guitar riff recalls yet another Pedestrian Verse song, “Dead Now”—Baker confesses, “Nobody deserves a second chance, but honey I keep getting them.” She more than deserves however many chances she thinks she’s getting because she’s managed to write three near-perfect records in the past half-decade. Her music is predicated on the fact that, as she sings on album closer “Ziptie,” “everything I do makes it worse.” But in sharing her pain in slightly different ways throughout her growing body of work, whether via quiet guitar soundscapes or fist-in-the-air anthems, she’s becoming not only the most relatable artist of her generation, but also arguably its best.

Steven Edelstone is the former album reviews editor at Paste and has written for the New York Times, Rolling Stone, the Village Voice and more. All he wants is to get a shot and beer combo once this all blows over. You can follow him on Twitter.