The hard truth is, no matter how many albums we review each year, there are always countless releases that end up overlooked. That’s why, this month, we’re bringing back our

No Album Left Behind

series, in which the Paste Music team has the chance to circle back to their favorite underrated records of 2021 and sing their praises.

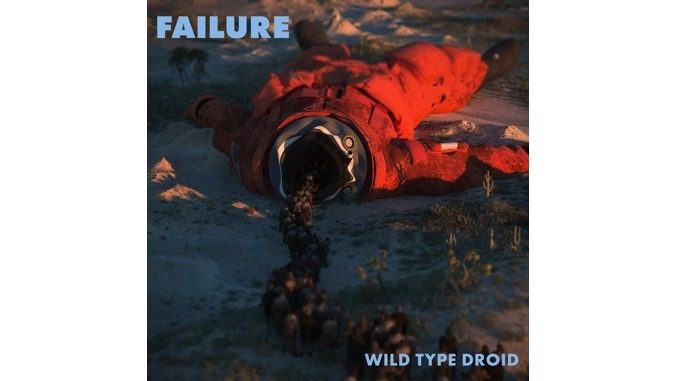

Reunions, as we all know, are a tricky business. As much as we might pine for our favorite bands to come back, very few of them truly recapture their old sparks. When Failure returned with a new album in 2015, the L.A. trio had to follow up on almost 20 years’ worth of legend that had accumulated around their 1996 swan song, Fantastic Planet. An era-defining work in so many ways, Fantastic Planet epitomizes ’90s alt-rock/alt-metal tropes alongside other canonical titles characterized by a combination of chunky guitars, radio-friendly melodies and walls of cymbal wash: Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream, Stone Temple Pilots’ Purple, Soundgarden’s Superunknown, Tool’s Aenima, Weezer’s debut, Helmet’s Betty and so on.

Much like their peers, Failure were celebrated—by a modest, but dedicated cult following that included members of Interpol, Deftones, Tool, STP and others—for putting a unique twist on cleaving guitar riffs that verged on metal while simultaneously emphasizing the non-heavy aspects of their sound. At the group’s creative core, multi-instrumentalists Ken Andrews and Greg Edwards were more closely aligned with The Beach Boys, Pink Floyd and The Cure than anyone in the metallic-edged movement they were considered part of. If anything, Failure represented a kind of warped ’90s reconstitution of psychedelia.

If, for example, the progression from Pet Sounds to The Wall was analogous to the jump from Willy Wonka to Robert Altman’s 3 Women, Failure’s 1994 sophomore effort Magnified paralleled the way Twin Peaks lurked at the margins of pop culture, luring audiences down rabbit holes into unprecedented realms of darkness. Above all, Edwards and Andrews were able to create a spellbinding sense of atmosphere. Each brought a signature approach to both guitar and bass, and their trademark was to weave together dissonance and harmony for an effect that was sinister, yet oddly beautiful.

Wild Type Droid, the third studio album of Failure’s second act, showcases this aspect perhaps more than anything the band have ever done. And if there were any lingering doubts as to whether Failure could still conjure that one-of-a-kind magic as reliably as they once did, Wild Type Droid should quell those doubts once and for all. While true to the band’s original essence, the album also showcases newer elements that very much reflect the moment we’re in and—crucially—voice the prevailing unease about where we might be headed.

The song “Undecided,” for example, swaps the stacks of amplifier distortion and crashing drums of old with sparkling-clean guitar lines, synth bass, a touch of twang and a groove from longtime drummer Kellii Scott that manages to be funky and somber at the same time. By restraining his forcefulness, Scott actually reveals a different kind of power in his playing. And across the board, the band forgo the bombast and density of their classic material, favoring an airy, almost astral approach that befits all those hallucinatory images that have been taking listeners on head trips since the ’90s.

“Undecided,” in fact, opens with its protagonist ruminating on a flight from Seoul, Korea, to an undisclosed destination. If the resemblance to the opening scene from William Gibson’s cyberpunk classic Mona Lisa Overdrive is purely coincidental, it’s hard to resist reading the author’s prescient message into these lyrics, which were written in the context of a present that looks an awful lot like the once-distant future Gibson described: “I need to wake up / Make my way back to the moon,” coos Andrews, his voice as velvety and lilting as it’s ever been. “I need to go now / while the ocean’s still blue … ”

Fans, of course, will immediately recognize Edwards’ use of space as a metaphor for disconnection from the self—the driving theme of Fantastic Planet, named after René Laloux’s animated sci-fi film from 1973. In a new twist, however, Edwards stresses in the press materials for the new album that it’s time to “abandon the space iconography” for good, describing the new material as “a return to earth” at a moment when “all minds have been called back to their bodies,” because “there’s a lot to attend to right in front of us.” If Edwards (who also plays in Autolux) wants to make the case that Failure’s music has moved beyond what we might typically associate with the term “space rock,” then fair enough. One could almost view album opener “Water With Hands” as Failure’s answer to Gary Numan-style new wave, except that the song contains too many modern elements to frame it as a retro tribute.

Just as they were in the mid-’90s, Failure are onto something that points the way forward. Which is precisely why, in light of lyrics like “I’m killing the past / so that my body can stay,” we can also view Wild Type Droid as the apotheosis of a new kind of space rock that Failure, more than anyone else, are perfectly positioned to set in motion. As human society continues to blur the line between artificially mediated sensation and what it means to be alive—a premise that could only be understood as fiction when it emerged in Gibson’s work prior to the advent of cyberspace, a term he coined—it becomes all the more imperative that we value the inner space Edwards has always tried to reach in Failure’s music.

In any case, he and Andrews have retained both the eeriness and accessibility that distinguished their songwriting partnership from day one. Listeners who found classic Failure tunes like “Bernie” and “Frogs” irresistibly unsettling will be shocked by how gripping the experience of losing oneself in the climactic section of a new song like “Headstand” can be. Likewise, “Bad Translation” rivals the sprawling density of “Heliotropic” and “Daylight,” the one-two punch that closes Fantastic Planet on such an epic note.

Throughout, Wild Type Droid percolates with such creative vitality that it allows listeners to imagine a world in which Failure not only never went away, but also never lost their hunger for growth. Whether we continue to categorize their music as “space rock,” per se, the album necessitates that we stop viewing them as a ’90s act altogether. As we could only hope from any band that returns from a lengthy absence, with Wild Type Droid, Failure honor their legacy while cementing their place in the here and now.

Saby Reyes-Kulkarni is a longtime contributor at Paste. He wrote at length about Failure in the liner notes to the band’s 2020 box set 1992-1996. You can read his work, listen to his interviews and playlists at feedbackdef.com, and find him on Twitter.