Listen to this article

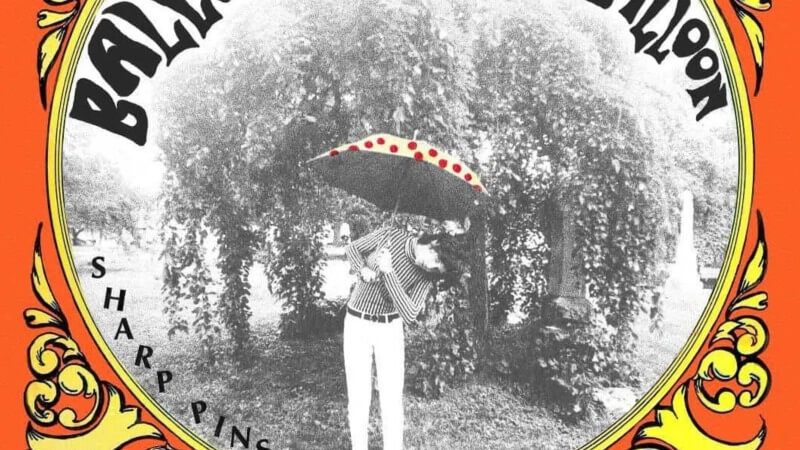

It’s almost impossible to listen to a Sharp Pins song and not hear a deluge of musical references. The buzzy solo project of Lifeguard’s Kai Slater is a paragon of ‘60s revivalism, with tracks that pair the jangly waves of a Rickenbacker with sugary layers of Beach Boys-esque vocals. The Rickenbacker is a nod to The Beatles, though Slater humbly uses a knockoff—he recently told Paste he’s decidedly not a guitar snob. True to form, Sharp Pins’ latest entry, Balloon Balloon Balloon, feels transported from the universe of mid-century mod pop, wearing every influence right on its tailored sleeve.

While Slater has clearly absorbed the styles of a great deal of artists, it feels reductive to attribute the sonic flavor of Sharp Pins to merely his precursors: running through each song is the distinct presence of Slater himself. The Sharp Pins style is an exciting collage—plastered with each errant song that’s entered Slater’s lexicon and brimming with the vast musical output of the half-dozen bands he’s been a part of since his teenage years. His references aren’t imitative or cheap nostalgia-bait, but a sincere appreciation for an era of music that’s come and gone. The lo-fi ballads of Balloon Balloon Balloon seem to recall the murky, downtempo tracks of Dwaal Troupe, one of Slater’s many offshoot bands (and my personal favorite project of his). “Gonna Learn to Crawl” feels cut from the same cloth of a Dwaal Troupe track like “Gym Shoe Rocket Show,” a grainy daydream of a song, replete with layers of Slater’s pleasantly androgynous vocals. “Gonna Learn to Crawl” exemplifies his penchant for flipping registers and skimming through his falsetto. His voice feebly hangs over the track as if being sung from the next room over.

Most of the songs on Balloon Balloon Balloon were written in Slater’s bedroom in Chicago, during rare stints in between touring with Lifeguard. He wrote as he recorded, typically only tracking one take per song, each on a TASCAM Porta One. The staunchly physical recording process gives the songs a filmy layer of warmth that digital recordings simply can’t recreate. Guitar strings creak and buzz, voices crack—the little human imperfections typical of live performance make their way into the songs, granting the record an air of spontaneity. Slater’s “first thought, best thought” mentality means the songs often only make half-sense, with some lyrics reading like a dizzy stream of consciousness—and it’s best to give into the perplexity. Slater often trades logic for emotion, letting incongruous images estimate a feeling rather than tell a straightforward narrative. The album’s opener, “Popafangout,” builds its melody from the line, “Oh popafangout / She don’t know what you’re shouting about.” Is the title a command for a vampire to pull its teeth? A tired parent begging their kid on Halloween to take out their Party City plastic veneers? I don’t know, nor do I want to; the song’s intrigue comes from its lack of clarity. Slater’s lyrics are sometimes mere accessories to a specific song’s sonic landscape, which can be tough on a first listen, but as you sink into his universe, the ramblings start to feel coherent.

The shimmery single “Queen of Globes and Mirrors” shows off Slater’s personal brand of whimsy, with a narrative that imagines the titular monarch “sailing through a helium tide” and traversing gardens where “nymphos smile and June resides.” He seems to be canonizing his own kind of mythos, gathering a band of illusory figures ranging anywhere from “Talking in Your Sleep”’s “sad lady of no one” to “I Could Find Out”’s “Sweden dispatcher.” He includes himself in this world of magical realism, too: “All the Prefabs” metaphorizes the unconventional relationships he has with his recordings. He sings “I got small / stepped inside the radio” like he walked right into a fuzzy FM signal—which may explain a few things.

For all of his colorful figurativism, Slater doesn’t completely veer from legibility. Hiding between stretches of circuitous chatter are peeks of vulnerability that are spelled out in more definite terms. “(In a While) You’ll Be Mine,” is an anxious love song, laying bare the insecurity of a loved one finding someone new. “Suppose you were lonely, what could you do?” Slater sings. “Talk to the lonely people inside of you?” On the other hand, “Maria Don’t” is impossibly sweet, a McCartney-level love song that breathes with unabashed affection. The song is an extended plea that leaves Slater crying out in a wispy tenor, “Oh Maria don’t cut my heart girl / Oh Maria tell me if I’m to blame.” It seems heartbreak, or even imagined heartbreak, elucidates a sort of clarity that’s been tamped down elsewhere. The sincerity of these tracks paired with Slater’s fuzz rock ramblings helps the album reach its own kind of homeostasis.

After spending most of his teenage years writing and recording, it’s a wonder Slater has anything left to give. But Balloon Balloon Balloon doesn’t leave the impression of an artist that’s running low on his supply. If anything, the album is proof that Slater can work with a threadbare setup, in total isolation, with next to no time on his hands, and create a record with such a specific and identifiable mood. Sharp Pins occupies a specific sonic niche, one of muddled melodies and buzzy feedback, that can sometimes be hard to take in large quantities. Balloon Balloon Balloon is a slow burn of a record that might take time to click, but if you give it the space it deserves, savoring it in small doses and letting the words ruminate, there is so much to be discovered.