It’s one the strangest, most disturbing, yet weirdly fortuitous stories in the history of rock and roll. And ZZ Top founder Billy F. Gibbons proudly knows it by heart.

As detailed in the 2008 book by Pope Brock, Charlatan, and the 2016 Sundance Film Festival documentary it inspired, NUTS, it’s the unbelievable tale of John R. Brinkley, a former telegraph operator who fancied himself a glandular specialist, who—in gullible 1920ss and ’30s America—began transplanting goat testicles into humans as a cure-all for 27 ailments, starting with impotence. To popularize his procedure and other various elixirs, he opened his first Kansas radio station, KFKB, in 1923. But after being shut down Stateside in the wake of countless fraud, malpractice and death suits, he cleverly relaunched radio broadcasts in 1932 from his powerful XER Border Blaster base in Mexico, which later morphed into XECR.

In 1942, “Doc” Brinkley would die penniless, after being hounded by determined AMA activist Morris Fishbein, who was constantly trying to enlighten his quack quarry’s deluded, Trump-like following. But not before the man’s one trailblazing had caught on, laying the groundwork for modern media—to pad his daily barrage of ads, Brinkley began adding musicians, offering airtime to nascent folk and country artists who had a few songs to peddle. By the time the Texas-based Gibbons tuned into XECR—along with The Blasters’ Alvin brothers, Dave and Phil, in Downey, California—the focus had shifted from advertising to a truly remarkable and influential cornucopia of talent that inspire the former’s classic early ZZ Top anthem “Heard it on the X” and the latter band’s signature “Border Radio.” The Border Blaster broadcasts were so powerful they couldn’t be ignored by any self-respecting young guitarist who was on the lookout for new sonic input. Pre-internet, kids, believe it or not, radio was quite a big deal.

Those X-gleaned influences, of course, would filter into ZZ Top, the Nudie-suited, Houston blues-rock trio Gibbons, now a still-youthful 71, formed in 1969 with bassist Dusty Hill and drummer Frank Beard. And the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer has always stayed true to those Border Blaster roots, even as his group found mainstream appeal with more streamlined mid-career albums like 1983’s Eliminator and 1985’s Afterburner, and the definitive chart hits “Legs,” “Gimme All Your Lovin’” and “Sharp Dressed Man.” And although his creative path would diverge into fun outlets like an animated appearance on King of the Hill, a recurring on TV drama Bones, and even his own brand of BFG Hot Sauce, Gibbons is still delighted to get down and dirty on his latest solo salvo, Hardware, backed by co-guitarist Austin Hanks and visionary ex-GNR drummer Matt Sorum, who also directs the trio’s videos. Gibbons’ riffs are bone-crunching, his voice still pitbull-snarling on a chant-along “I Was a Highway,” an R&B-blunt “More-More-More,” the slinky “She’s On Fire,” and even “Stackin’ Bones,” when countered by the sweet “Ooh-la-la” chorus of Larkin Poe. But even the man’s take on The Texas Tornados’ once-playful “Hey Baby, Que Paso” sounds downright ominous now, as do his Tom Waits-school spoken-word musings on “Desert High”; “The desert toad takes me for a ride / The Lizard King’s always by my side,” he observes, and it’s an ode to where Hardware was tracked—Joshua Tree—and maybe all things Border Blaster, as well. No goat gland augmentation required.

Paste: So you know the story of John Brinkley, right? And how he started the strange XER radio station that you used to listen to as a kid, the one that ZZ Top praised in “Heard It On the X”?

Billy Gibbons: Old Doc Brinkley? Of course. And you bring up something so inspirational. And I guess it’s fair to say that what was coming across the airwaves, loud as a police call, was all of that craziness on that first powerful Border Blaster radio station. But let’s go back a bit. When commercial radio started coming into play, the United States and Canada conveniently divided up the entire AM wavelength between themselves, leaving nothing for Mexico or Cuba. And shortly thereafter, the establishment of the FCC, the Federal Communications Commission, they put a ceiling of 50,000 watts broadcasting power. Well, when Doc Brinkley got run out of the U.S., he found his way down to Del Rio, Texas, right on the Mexican border, and then he tiptoed down into Mexico and approached the authorities to open up a radio station, but not with 50,000 watts. His suggestion was 500,000 watts. And on a good day, you could hear him broadcasting right on the Mexican border with Texas all the way to the Hawaiian Islands and parts of western Europe. So he was intent on being heard. And—Lord have mercy—being heard he was.

Paste: And so many country artists came through there, Del Rio became known as Hillbilly Hollywood, right?

Gibbons: Very true. And those broadcasts were cut up into 15-minute segments, which meant that a lot of different performers got to establish themselves by broadcasting over Doc Brinkley’s airwaves. And Hillbilly Hollywood it was. In fact, there were some interesting discoveries recently made. Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys made several stops down there in Del Rio, and some of the transcriptions just recently emerged—hopefully, they’ll be released.

Paste: Everybody stopped by his station—Patsy Montana, Red Foley, Gene Autry, the Carter Family.

Gibbons: All of that, and that goes back to the early days. And then on into the ‘60s, when Wolfman Jack took over the late-night spot. And you know the interesting part about XERF? RCA had to go back to the drawing board to create such a powerful transmitter. And the broadcasts were only heard in the evenings. The transmitter got so hot that they had to let it cool down during the daylight hours, and in the evening, when the sun set, that’s when they re-lit the fuse, and I’d say about 6 o’clock in the evening was when the broadcasting cranked up, and they would go until 30 o’clock in the morning. And then they had to let it cool down and then it would start all over again. But you could hear everything from piano lessons— Vic Manners and his Piano Lessons—and then you could get 100 baby chicks for $2. There were soothsayers and all kinds of acts. I even had a short stint as The Reverend Willy G. [He goes into a Wolfman-Jack-gravelly on-air voice.] “Broadcasting over XERF on your radio dial!” I did a 15-minute slot there back in the day. I was about 18, and somebody said, “You know, you ought to go down there. It’s only $75 for a 15-minute set!” And we did it on a dare. And it was interesting. A buddy of mine had learned that there had been a delivery of Chinese slippers, and they were all left feet, so they couldn’t sell ’em. So we bought ’em for a dime on the dollar, and we advertised them as “Thought-Provoking Soul Slippers.” We’d take a rubber stamp and stamp in your favorite Psalm, so with every step you took wearing these Thought Provoking Soul Slippers, you’d get 1,000 prayers. So we were just clowning around. But then the donations started pouring in, and we got scared. But I think it’s fair to say that the real eye-opener there was Wolfman Jack. And if you listen to some of those original air-checks from XERF—I’ve still got a bunch of this stuff on reel-to-reel tape from way back in the day—you can hear it. I’ll have to send you a couple of the Reverend Willie G sessions. [He goes into his gruff broadcasting persona again.] “This is Reverend Wille G, coming to you from XERF down on the silvery banks of the Rio Grande river. Now I know some of you men have been spending money on whiskey and cigars, and some of you ladies have been spending money on cosmetics and nylons. And I know! I know that when the salty seawater … ” Oh, it goes on and on and on …

Paste: Wait a minute! That voice—where have I heard it before? Oh yeah—on your new Hardware single “Desert High,” where your vocals are almost spoken-word.

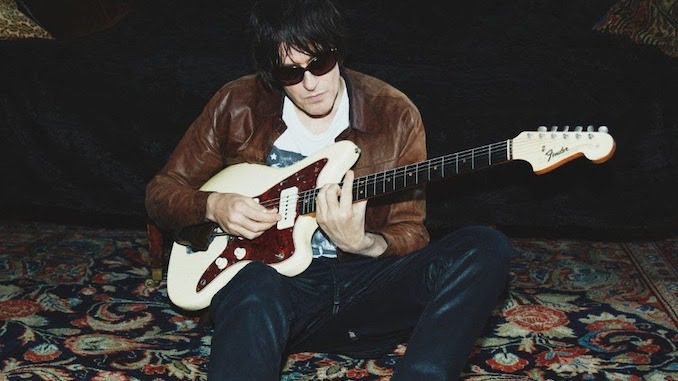

Gibbons: I think so. Yeah, man! And that brings up another mystery element—of what it’s like to be down there in Joshua Tree. You know, you can read about Joshua Tree, you can even see photographs of Joshua Tree. But it really takes a trip there, and standing in there in those desert sands. And when the energy overtakes you, it’s really something to behold. It’s really cool. And we’re not the only ones. People have been traipsing through those parts for ages. But lemme back up a bit and give you some background on how this new album Hardware came about. It was Matt Sorum that rang up out of the clear blue, way back in June, and he said, “I don’t know about you, but I’m ready to do something. And making loud noise is right up our alley, so how would you feel about going out and checking out a new recording studio?” And I said, “Gee whiz! That’s music to my ears! Whaddaya got in mind?” And he said, “Oh, there’s a place out near Joshua Tree.” And I initially suspected that he was referring to Rancho De La Luna, where I had worked with Josh Homme and his Queens of the Stone Age project. But Matt said, “No, it’s right across the highway.” Little did he tell me that it was not only across the highway, but it was 20 miles back into the desert. But sure enough, we teamed up, we went from Palm Springs down the road there, and when we arrived, I thought, “Oh, 30 minutes, we’ll have a look around.” Well, those 30 minutes turned into three months. We walked through the front door, and we didn’t leave until we had wrapped up this album project. And even better was the fact that the studio had already placed a scattering of instruments laying about, because when we arrived, Matt didn’t even have a drum stick, and I didn’t have a guitar pick. But—lo and behold—in the studio, to my delight, they had an old Fender Jazzmaster guitar, leaning up against a Fender reverb tank. And Matt tuned up a set of skins that was in a corner, and off we went. And the first crack outta the box was the single that was released in the last couple of weeks, “West Coast Junkie.” “I’ma West Coast junkie from a lonesome Texas town … ” But the engineer said, “Well, it’s no secret, Billy, that you became friends with Jimi Hendrix—didn’t Jimi say on one of his early records that ‘You shall never hear surf music again’?” And I said, “Yeah. But maybe it’s time to let this cat outta the bag.” Because there was that familiar old surf sound from the ‘60s—it’s back!

Paste: Along with a cool cover of “Hey Baby, Que Paso.”

Gibbons: Sí, señor! We did a version of that as the closing number. We were letting the computers catch up to speed, and we were playing DJ in the control room. And I’ve actually got a version of “Hey Baby, Que Paso” earlier than the Texas Tornados’, earlier than the Sir Douglas Quintet. It’s the first recorded version that Augie [Meyers] recorded on his own. And I called him up and said, “Hey, Augie—we’re sitting around in the studio, and we’re listening to different songs, and we came across ‘Hey Baby’ from the original 45 rpm single. But we can’t quite make out the second verse, we can’t quite make out what you’re singing.” And he said, “Oh, it’s fake Spanish. We were looking for a rhyme to the words ‘San Antonio.’ But since you’re in the studio, why don’t you take a stab at re-recording a version?” And I said, “We will do just that.” And he said, “And while you’re at it, you’d better make up your own second verse!”

Paste: I respect the fact that you’re a serious collector. Of cars, obviously.

Gibbons: Oh, yeah. In fact, I’m about to start a new publication that covers our favorite subjects—cars and guitars. And actually, it was the excursion into the studio to create Hardware that re-enlivened our interest in those early examples from Fender, like the famous Fender Jazzmaster and its unusual sound, which, of course, led to the next incarnation the Jaguar. So we are off on a tangent now—we are dead-set on going early Fender again.

Paste: So collecting guitars is just as important.

Gibbons: I think so. I had an immediate fixation on two guitars that were very inspirational. Down the street when I was growing up, there was a teenage couple of brothers who had started a band, and they used to practice in their front yard. I was just a few houses down, and from my bedroom window, I could zero in and catch their rehearsals. And the one brother had the 1961 version of a Les Paul—it’s when they switched over to what later became the SG shape. And of course, that first year, it had that weird sideways whammy bar. And the older brother also played guitar—it was an interesting group, just two guitars and drums. And Bobby was the younger brother, playing the ’61 Les Paul, and the older brother Mickey, he had the first Fender Jazzmaster I had ever laid eyes on. It was a sunburst Jazzmaster with the brass anodized pick guard, but it had a maple neck. It was a rare Jazzmaster. So some day, I hope to track that one down.

Paste: But it’s interesting to note that you actually played with Les Paul.

Gibbons: Yeah, man! In fact, someone told me that you can catch that exchange on YouTube. But the funny thing was, that was when he was doing [a weekly residency at New York club] Fat Tuesday’s, and we had a night off in Manhattan and we were invited to go down. And I said, “You know what? It would be great to see Les Paul, but it’s no secret that if he spots you in the audience, he’ll demand that you come down and play. So send word that we’d just like to be a fly on the wall and enjoy the evening.” But we had no sooner walked in than he said, “Oh, my good friend BFG is in the house! Come on up and play!” And I couldn’t ignore it. But little did I know that the guitar I was handed was Les Paul’s secret weapon—it was out of tune, and he had superglued all the machine heads so you couldn’t tune it! And he’d let you fuss with it for a few minutes, and then finally he’d let the cat out of the bag and say, “Okay—fun’s fun. But here’s the real deal.” But that was quite an experience—getting to play with Les Paul.

Paste: At this point, though, who haven’t you befriended or played with? You seem to be pals with everybody.

Gibbons: Well, as we bow out here, I have to include the fact that Gilligan [Stillwater, his wife of 15 years] and I had just made a return trip—we made an automobile excursion down to South Texas, just to get out and get some fresh air. And on our way back, we made a detour through Austin, and we caught the Sunday afternoon gathering where our buddy on Hammond B-3, Mike Flanagan—who I work with in our other outfit, The Jungle Show—and the whole gang had gathered. So it was Mr. Mike Flanagan, Sue Foley was present, Chris Layton drums, Jimmie Vaughn was in the house, as well as—believe it or not—Van Wilks and another jam-session standby, Anson Funderburgh, who got up onstage. It was a great Sunday afternoon.

Paste: Which one of your cars do you actually dare to drive on a road trip like that?

Gibbons: Well, the two newest creations—which you can find on YouTube—are, we did a brief stint with Jay Leno when we crawled behind the wheel of our bad little sister to the famous red car that you see pictured on the album cover of Eliminator, ZZ Top’s Eliminator album. And now, with the release of Hardware, I put the bad little sister on there, another ’34 Ford. And this one is a fender-less version, but it’s rarin’ to go! I hope to be passing by your way in it soon, now that everybody else is getting back on the road …