Listen to this article

The German Romantic poet Novalis once wrote of his search for “a single secret word” that would strip the world of its crude veil and reveal the glorious truth beneath. He never named the word, leaving it as the symbolic key sought by all Romantics—the one that would halt the onslaught of reason and restore humanity to its mythical, spiritual roots. It’s been a long time since the Romantic age, though. If there is truly a “word,” so to speak, it’s safe to say that it has not yet been voiced.

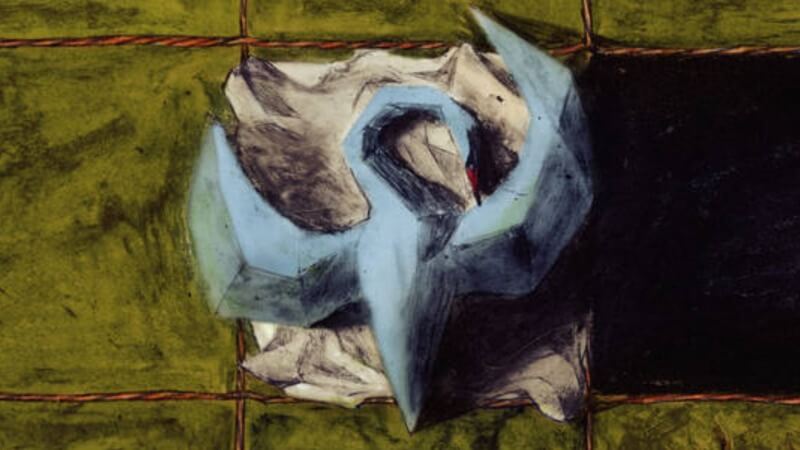

Roughly 225 years after Novalis’s unspoken question, an unlikely source has (presumably unintentionally) posited a new answer: “Now is the fake,” croons 22-year-old Irish singer-songwriter Dove Ellis on the opening track to his debut record, Blizzard. “The real is the word.”

It’s something of a contradiction in terms, both an extension of Novalis’s original conceit and a total rejection of it; there is a veil (the “now”) that can be dissolved by a word, but there’s nothing mythical, spiritual, or secret about the word itself. It is, simply, the real. Contrary to strains of the Romantic imagination, “Love is not / What’s in your dreams,” Ellis sings elsewhere on the album. “Love is / The sweeping hair that is protecting your sleep tonight / Love is / The snow pooling around your shoes.” The beauty and truth of our world lie not in its mysticality, but in the mundane and material.

There’s not a thesis statement to Blizzard, per se, but the more I listened, the more I returned to that same sentiment, albeit from multiple angles. Naturally, it resonates thematically across the record—within individual songs (“Little Left Hope,” “Love Is,” “Heaven Has No Wings,” “It Is A Blizzard,” and so on) and as a subtle connective tissue across the arc of the album. Even sonically, the album insists on the tangible: it’s littered with instrumental creaks and scrapes that sound almost accidental—an off-beat brush of a stick against a drum, a faint blurted shriek from a reed, a barely-there tick of a metronome. You feel as if you’re in the room, the cracks of Ellis’ made-for-indie-folk voice ringing in your ears.

If we want to be Doylist about it, though, there’s also Blizzard’s promotional rollout, which—much like Heavy Metal last year—purposefully dropped after year-end rankings solidified, guaranteeing it would be placed on exactly none of them (until the following year, at least, because both albums are simply too good to fall under the radar). There’s Ellis himself, a figure of near-total mystique in his own right, as he cropped up virtually out of nowhere to open for one of the year’s biggest bands. Even with Blizzard on the horizon, he eschewed the usual hype cycle of profiles and promotion, instead merely presenting music and a handful of headline dates. This, in other words, forces listeners to interface directly with the songs themselves, isolated from the trappings of celebrity, narrative, and status. The music is the real, after all. The rest is the fake.

Between the social-media-inspired obsession with presenting an infallible public perception, the TikTok-inspired tendency towards rapid bursts of catchy melodies intended to farm clicks, and the radio-inspired production that smoothes out the edges until they’re flat and glistening, many musicians today seem to struggle with the authentic portrayal of emotion—often delivering the idea of vulnerability instead of the feeling, sound, and experience of it.

Dove Ellis does not have that problem. In fact, Blizzard seems to be tuned specifically for emotion, the arrangements ebbing in and out to complement the rise and fall of intensity, Ellis’ whispers and bellows typically foregrounded in the mix—a smart choice, considering he can (and often does) stuff a word with enough raw feeling to bring you to your knees. He and his band have an innate knack for dynamics of both the sonic and structural variety; each shift is carefully pitched at the precise emotional tenor to leave you reeling. Almost no song on the record stays in a single mode, always pushing forward then receding back with the fevered confidence of a high tide. It’s a stunning record taken in full; any amount of success with the age-old balancing act of cohesion without homogeneity is always cause for celebration, but getting this close to it on a debut feels nothing short of remarkable.

The production is kept light and dry, adding an immediacy to the deceptively dense arrangements: percussion from Matthew Deakin and Jake Brown grounds the restless tempo while Reuben Haycocks and Louis Campbell’s guitar fleshes out the rest of the sonic foundation. Lili Holland-Fricke’s cello, Saya Barbaglia’s strings, and Fred Donlon-Mansbridge’s reeds, on the other hand, flutter around the edges, feeling almost like characters themselves. Yet the emotional depth of the album rarely inhibits Ellis’ apparent ability to churn out radio-ready hooks. There are the obvious culprits in more upbeat songs, like the anthemic “Love Is” and the Irish jig of “Jaundice,” but don’t overlook the first two tracks: the keening chorus of “Pale Song” now lives somewhere just behind my eyes, and all three distinct melodies (verse, bridge, and chorus) from “Little Left Hope” have individually taken up permanent residence in the house of my mind.

Ellis’ voice, meanwhile, remains the centerpiece—a flexible instrument that winds through octaves and moods with disarming warmth. To be blunt, he’s been blessed (or cursed) with what might be the Platonic ideal of a white male indie-folk-rock voice. Every breath seems to conjure a reference: namely, a Jeff Buckley cry, or perhaps a Thom Yorke murmur, or maybe a Cameron Winter vibrato. I even heard Will Toledo in there somewhere (the refrain in “Love Is” calls to mind Teens of Denial-era Car Seat Headrest), as well as Andrew Bird (the whole of “Jaundice”) and, for a split second, Xiu Xiu’s Jamie Stewart (the eerie near-whisper at the end of “To The Sandals”). Crucially, though, it never feels derivative. Where many peers echo past voices to trade on nostalgia, Ellis uses those echoes as scaffolding for his own tonal world—one where sincerity is reasserted as avant-garde. It reclaims the sincerity of the folk lineage without retreating into pastiche.

With a voice like his and arrangements like these, Ellis could probably make even the phone book sound evocative if he put his mind to it. But the gentle force of his intent is most powerful when aimed at the smallest targets: the mundane, material, and real. The cut of a lover’s cheekbone, the choked silence of lunch in an empty hall, the flies hovering around a rotted plank of wood, the three monogrammed cups a father brought back from a market.

A few songs risk diffusing this focus, spreading it across a broadly sketched, intentionally obscure narrative. “Heaven Has No Wings” describes “babies wailing on a tightrope,” a man holding a scythe and petting falcons, a metaphor about growing grain—all interesting fragments, to be sure, but ones that never quite fit together. Emotion survives through Ellis’ delivery and the swelling arrangement (again, phonebook), but the song’s meaning feels evasive rather than elusive, rendering its climax somewhat neutered; the catharsis doesn’t feel quite earned.

But when all of that intensity and emotionality converges on a single image that boasts staying power in its own right, the record transcends the (already impressive) sum of its parts and reaches utterly new heights. “When You Tie Your Hair Up,” for instance, is wrenching precisely because its heartbreak is catalogued in the language of routine. There are myriad songs about dying relationships, but few that soundtrack the ache of domestic repetition with the burgeoning overwhelm of loss: “As we tire of working / The skin creased in our palms cuts deeper each night,” Ellis murmurs, voice fragile enough to be bowed over by a light breeze. “At the cusp of the evening / I retire, close my door, then you bid me goodnight.” The cello, drums, and guitar build and build and build, almost spilling over into that desired catharsis—before dropping away entirely, leaving him to whisper, meekly: “Annie, won’t you come back into my home again?” He repeats it, again and again, intensifying with each iteration until he’s downright wailing.

The point here isn’t a plea for lyrical transparency; we don’t need to know what happened between the speaker and Annie. The story of “Pale Song” is likewise opaque, but its perspective and feeling is palpable in lines like “Seven in the ground / I put them there myself / Oh soil holds a mouth / Momma I’ll join them in my mound.” Regret and yearning pulse through the bittersweet Christmas vignette “It Is a Blizzard” and the spare, open closer “Away You Stride.” I’d argue that the songs are stronger for all that they leave unsaid—but only because they do say enough to allow the rest to fall to interpretation. These songs work because they offer enough detail to invite interpretation without dictating it. They extend an olive branch but never brandish it (unlike, say, “Love Is,” whose directness tips toward the literal).

That push and pull between the tangible and the transcendent defines the album’s deeper current, nowhere clearer than in Ellis’ repeated return to the myth of Icarus. In his hands, the tale feels less like a parable than a gravitational force, an emblem of yearning and consequence. “Pale Song” warns, “You might like getting hot / But you won’t like getting spun,” while “Little Left Hope” reimagines the moment just before the fall (“Carry me to the end / Where the air and the wing are one / A nameless stroke of sun / Until they’re memory”) and then the plummet down, nothing left but “wings and a word.” In “Heaven Has No Wings Itself,” birds ascend only to be “blasted down with fire and rain;” heaven itself has no wings, after all. But by “Feathers, Cash,” Ellis is already rethinking the myth from inside its limits: “I’ll still lift up my feather… that’s how far I’ll go.” The desire to rise remains, but the dream of transcendence has burned away, leaving only motion tethered to the world.

It’s the final track, “Away You Stride,” that brings the arc home—here, the speaker finally abandons those dreams of doomed wax wings in favor of simply grabbing a boat and setting sail. There’s no myth-making to be had here, only the mundanity of movement: “I’m heading further west, babe / Keep their cameras off my face / Remember me in action / Don’t remember me in space.” Only a boat, a hole in the chest the shape of a loved one left behind, and a vast ocean stretching as far as the eye can see.

In some senses, Blizzard takes all that Romantic yearning—for the pure, the mythical, the divine—and turns it gently earthward. The “word” that might once have promised access to the beyond reveals itself here as something humbler, truer: the real world right in front of you. That, ultimately, is the revelation the record offers; perhaps the veil was never meant to be lifted, only lived within. Perhaps the sublime has been there all alone, lying latent in the ordinary—in the snow pooling around your shoes, in the hair brushed from a lover’s face, in the ache of continuing after loss. Perhaps the real was always enough.

Casey Epstein-Gross is Associate Music Editor at Paste and is based in New York City. Follow her on X (@epsteingross) or email her at [email protected].