Comedian Robin Williams once called cocaine “God’s way of telling you you are making too much money”. This role may now have been overtaken by non-fungible tokens, the blockchain-based means to claim unique ownership of easily copied digital assets.

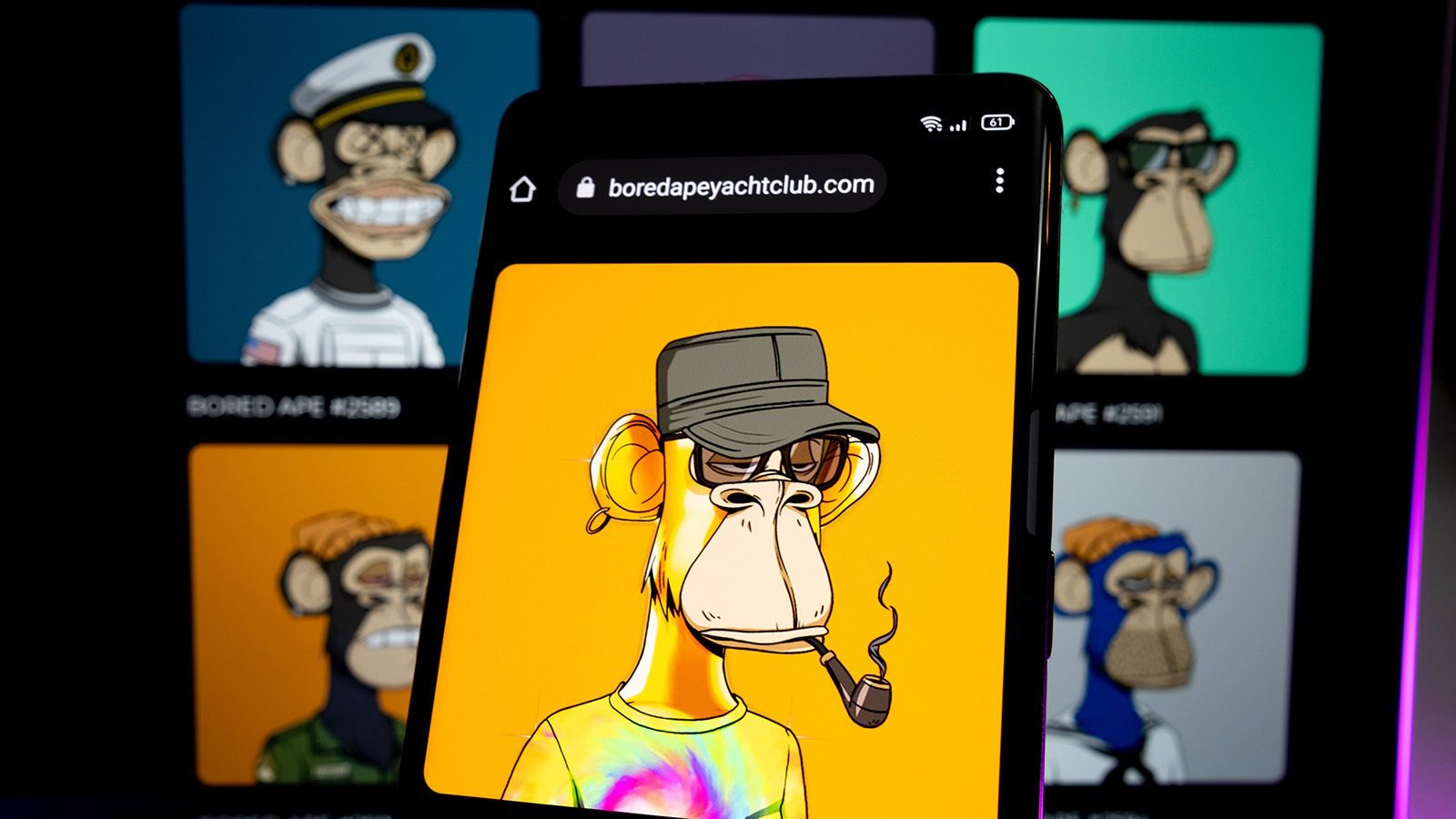

The latest NFT mania involves fantastic amounts of money being paid for “Bored Apes,” 10,000 avatars featuring variants of a bored-looking cartoon ape. Last month rapper Eminem (real name Marshall Mathers) paid about US$450,000 in Ethereum cryptocurrency to acquire Bored Ape No. 9055 – nicknamed EminApe, because its khaki and gold chain resembles what Eminem wears. It purportedly joins more than 160 other NFTs in the rapper’s collection.

The Bored Ape character seems derivative of the drawings of Jamie Hewlett, the artist who drew Tank Girl and virtual band Gorillaz. According to to the creators, each variant is “generated from over 170 possible traits, including expression, headwear, clothing, and more”. They say every ape is unique “but some are rarer than others“.

So what does Eminem now own? He has an electronic version of an image, which he is using for his Twitter profile. But then so does anyone who copies it from the internet. The only difference is that he has a record in a blockchain that shows he bought it. He also gets to be a member of the “Bored Ape Yacht Club” a members-only online space whose benefits and purpose beyond being a marketing gimmick are unclear.

That’s about it. The intellectual property (such as it is) remains with the creators. He is not entitled to any share of merchandising revenue from the character. He can only profit from his purchase if he can find a “greater fool” willing to pay even more for the NFT.

Which is unlikely. While publicity given to the rapper’s purchase certainly seems to have boosted demand, the average price paid for Bored Ape NFTs so far in 2022 is about 83 Ether (currently about US$280,000). Eminem may have been prepared to pay much more for the one that looked more like him; but would anyone else?

NFTs are a highly speculative purchase. The basis of the market is proof of unique ownership, which only really matters for bragging rights and the prospect of selling the NFT in the future. NFT mania arguably combines the most tawdry and avaricious aspects of collectibles and blockchain markets with celebrity culture.

The rise of the celebrity influencer

Eminem’s monster payment in particular has lent credibility to the idea these NFTs have value. But he is not the only celebrity who has helped attract attention to the Bored Ape NFTs.

Others to buy into the hype include basketball stars Shaquille O’Neal and Stephen Curry, billionaire Mark Cuban, electronic dance music DJ Steve Aoki, YouTuber Logan Paul and late-night television host Jimmy Fallon.

These well-publicised purchasers effectively act as a form of celebrity endorsement – a tried and true marketing tactic. It is a graphic example of the power of media culture to stoke “irrational exuberance” in financial markets. There has been a shift away from traditional investments and sources of investment advice. With prices disconnected from any future cash flows, there is less interest in forecasts from technical experts. Instead people turn to social media and “doing their own research”.

One survey in mid-2021 (polling 1,400 investors aged 18 to 40) suggested about a third of Gen Z investors regard TikTok videos as a source of trustworthy investment advice.

This has opened up the field for celebrity influencers.

A lot like Ponzi schemes

While not illegal, many NFT marketing ventures have some similarities with Ponzi schemes, such as that operated by Bernie Madoff (who sustained his fraud for decades by paying high “dividends” from the deposits of new investors).

Cryptocurrency markets work in essentially the same manner. For existing investors to profit, new buyers have to be drawn into the market. So too NFTs, with something illusory attached to the digital assets.

Some light on the worth of this attachment compared to the economics of NFTs themselves may come from the interesting (and also highly profitable) experiment by the (now not so) “young British artist” Damien Hirst – himself a master self-promoter.

Hirst’s well-publicised “The Currency” project has involved selling NFTs for 10,000 similar but unique dot paintings. The twist is that at the end of a 12-month period those who have bought the NFT must decide if they want the digital token or the physical artwork. If they keep the NFT the artwork will be destroyed.

No fundamental value

There’s virtually nothing humans can’t turn into a market. But increasingly there are speculative bubbles in things with absolutely no fundamental value. NFTs have joined Bitcoin and celebrity meme-based cryptocurrencies such as Dogecoin and Shiba Inu as examples of tokens with no intrinsic worth, which speculators just buy in the hope the price will keep rising.

Even Dogecoin, started as a satire on these excesses, is now valued at US$20 billion and promoted in Ponzi-like ways.

Some studies have suggested tweets or Facebook posts can now drive stock prices. Elon Musk’s tweets certainly seem to have a large impact on cryptocurrency prices.

We now appear to be in the monster of all speculative bubbles. The creators of assets like NFTs will do well. It is not so clear about the holders.

Nor will the impact of NFT crashes be restricted just to the NFT market. Speculators, particularly if they have borrowed heavily, may need to liquidate other assets as well. This is all likely to make all financial markets more volatile.

The larger the bubble becomes, the wider the contagion when it bursts.

Written by John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society and NATSEM, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()