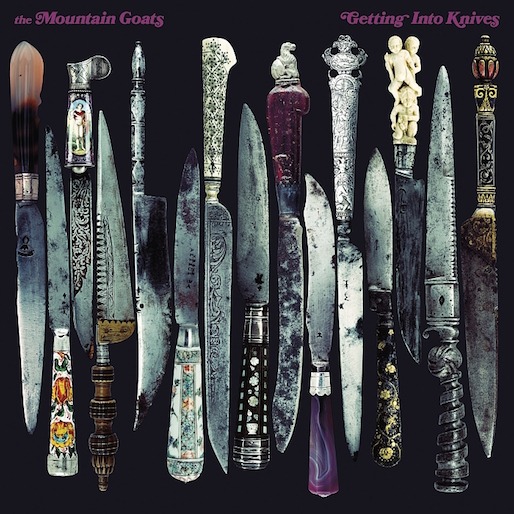

“How you gonna win when you ain’t right within?” Lauryn Hill once asked. This is a challenge to live by, a challenge so heavy that it’s hard to keep it at the forefront of consciousness. A question like this can only be faced through relentless self-examination, through trying to open up the book of what all happened, where you’re at, and what it is, exactly, you’re hoping for. Pop music has occasioned this kind of heavy reflection from the get-go and all along (“Do I really feel the way I feel?” Marc Cohn, “Walking In Memphis”), but nobody cracks the old psyche open quite like The Mountain Goats. They help us deal with ourselves. And in the COVID era, their latest effort, Getting Into Knives, comes at us as a nervous breakthrough that seems almost knowingly calibrated to address and give voice to the sense of unease that seems to saturate all possible perception. With Peter Hughes, Matt Douglas and John Wurster, John Darnielle deep dives into the human situation, finding the words that find the feeling. And over the course of 13 songs, the spell they cast confers a dark blessing that seems driven by a rare, intuitive conviction: Your shadow has something to show you.

Recorded within a single week with microphones purloined from the ruins of The Nashville Network, Getting Into Knives brought the band to Sam Phillips Recording, former haunt of The Cramps as well as Elvis of Tupelo. These two iconic bookends are deeply in keeping with the range of sound on offer. Producer Matt Ross-Spang enlisted the Rev. Charles Hodges, whose Hammond B-3 gave rise to Al Green’s sound as well as the Memphis trumpeter Tom Clary, and there’s a rockabilly feel alongside soul and even country, but no one genre is discernible for long. It’s as if The Mountain Goats contain multitudes and so can you. This method for seeing self and others more clearly is on offer on the album’s hardest-driving number, “As Many Candles As Possible.” Even under duress, one touch of nature makes the whole world kin, and, if we have an eye for them, kinship rituals can be spied arising before us throughout our everyday campaigns:

”When you see the risen beast in you nightmares

You treat him like a long, lost brother

But when you pass him on the streets of the city by day

You pretend you don’t recognize each other.”

Overcoming the temptation to dissociate from the beast without and within is among John Darnielle’s signature moves. Why front at the sight of danger when you don’t have to? If light is scarce in what Darnielle has referred to as a “data-poor environment,” compassion is called for. This includes a lobster, wolves, fish, and pigs, as well as human beings whose experience differs, whether slightly or radically, from our own.

Something like this imaginative practice is exemplified in every song on the album. Take “Picture of My Dress,” for instance. What began as a writing prompt on Twitter, initiated by the poet Maggie Smith provoked a reply which turned into a song John Darnielle imagined aloud would be better tackled by Mary Chapin Carpenter. From there, Darnielle conjures and gives voice to a divorcee travelling across the country taking pictures of her wedding dress in different contexts and locations. She pauses in the bathroom of a Burger King to note the presence of Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler on an overhead speaker (“He doesn’t want to miss a thing”), takes in the sights with a determined open-handedness, and also considers the challenge she faces as she tries to recover a sense of self: “I’m going to have to chase down the remnants of something special that you stole from me.”

It can be argued that every Mountain Goats album has at least one achingly earnest centrepiece. There’s still humor, but there’s also a poignancy that has one song sticking out a little and almost serving as key or a legend with which to discern the psychic terrain being peculiarly addressed this time around. This is one possibly helpful take on “Bell Swamp Connection.” Culture, we feel, is a crime scene: “Somebody’s always just about to put some awful plan in motion.” And amid eastern redcedars and “undeveloped” land, there appears a stone slab with some kind of scrawl to be discerned. To say more feels like a lyrical spoiler, but, if you aren’t moved to tears or at least a pang of familiar feeling by the chorus, you might be in need of an exorcism.

Speaking of wicked spirits, Getting Into Knives also includes an offering for a relatively small file of popular songs about popularity itself. Consider this question: “Is it any wonder I resent you first?” These words arise out of a form of psychic turmoil held at an angle through lyricization in a song that names the turmoil itself: “Fame” (David Bowie, Carlos Alomar, & John Lennon). Like a Gollum that’s learned to chill out long enough to pen some lines, “Fame” notes the fire, the misplaced passion, and the insanity of a phenomenon that “puts you there where things are hollow.” With “Get Famous,” The Mountain Goats shed light on this shadowy substance, scrying the lived fact of the condition for the best-selling curse it is:

”You arrive on the scene like a message from God

Listen to the people applaud

This is what you were born to do

Wesley Willis taught me how to write about you”

If you don’t know the name Wesley Willis, you’re going to want to look him up. Sometimes referred to as “The Daddy of Rock ‘n’ Roll,” he operated as an outsider artist whose songs often yield a vision of particular acts, (like Urge Overkill, for instance) which are simultaneously effusive, descriptive, but also evocatively ambiguous. For Darnielle to describe Willis as someone who instructed him in the task of writing about fame is illuminating. It makes the song a little more like a mystery text. It’s as if saying “Go on & get famous,” is a little like turning a character’s soul over to a fire that might refine but might also only consume it. You do you, and see what happens.

But lest any of this sound too grim, this is not the spirit of the album. That spirit is perhaps best captured with the toe-tapping opening number that emerges out of a strange, static-y cacophony. “Corsican Mastiff Stride” sets the stage for what will befall the listeners and accompanying players with this directive: “Put it all on the table and let it ride.” There are ghosts here with kind and bitter warnings concerning misdirected expenditure of soul and tales of rest beyond our world of luck and brutality. They’re momentarily housed in songs that seem to urge Joe Strummer’s encapsulation of punk rock, “exemplary manners to your fellow human beings,” a counsel of imaginatively open-handed hospitality to strangers, any one of whom might bear a righteous oracle. This includes those most estranged, at least for now, from their own humanity. As Darnielle observes in, “Tidal Wave,” “Even the proud, even the very proud, probably die on their knees.” Getting Into Knives summons such voices, inviting us to hold them at a creative angle whereby we can listen to them and manage them without drowning completely. It’s a healing exercise.

David Dark is an educator in Nashville and the author of The Possibility of America.