As his career in country music has taken off over the past few years, Kentucky-born-and-bred singer/songwriter Tyler Childers has proven to be a bit of a tough nut to crack.

On his two excellent first albums—2017’s Purgatory and 2019’s Country Squire—Childers sings eloquently about drinking and drugs, making music, missing his woman, raising hell and living the hillbilly lifestyle. He’s a top-shelf storyteller, but if you’re looking for lyrics that reveal how he feels about certain issues or current events, you’re out of luck.

Live, Childers is wild-eyed and workmanlike, cranking through songs with his killer band and only occasionally stopping to chit-chat with the audience, or even crack a smile. In interviews, he usually comes off as warm and polite, though not especially forthcoming. He seems already a bit weary of his success and/or his industry of choice. Perhaps he just values his privacy.

All of this is perfectly fine, of course. There is no rule that Childers must express his opinions through song or dance around on stage to prove he’s having fun. His style is his style, and it has worked well for him as he has quickly built a sizable nationwide fanbase of people who connect with his authentic twang, working-class anthems and credible perspective on life in the rural American South.

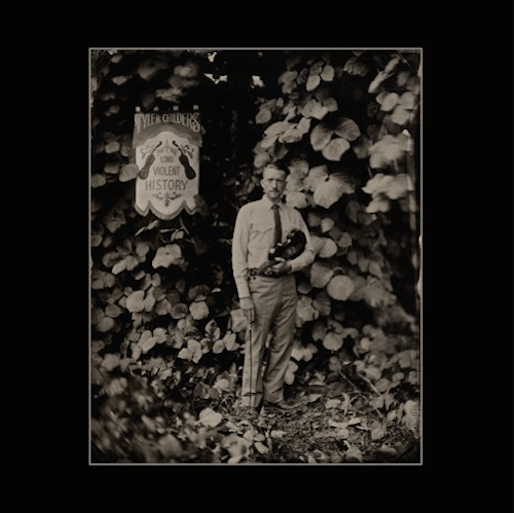

But even Childers is done playing it close to the vest after the year we’ve had. It’s not immediately obvious on his new album Long Violent History—surprise-released on Sept. 18—but to ensure absolutely no one misses the main point, Childers released a six-minute-long video along with the album to act as an introduction to the work. For clarity’s sake, let’s approach Long Violent History in three parts:

The fiddle tunes: The album begins with a fiddle-driven cover of Stephen Sondheim’s 1973 showtune “Send In The Clowns,” followed by seven fiddle tunes—six traditional, one modern—performed with the skill and certainty of a man who is still learning to play the fiddle, backed by a group of string-bending experts. (Childers has been fiddling for “under a year,” according to an essay on Long Violent History written by old-time music ambassador Dom Flemons). In the video introduction, Childers detailed his original goal for the project (“to make fairly legible sounds on the fiddle”) and the purpose of the eight fiddle tracks: “to create a sonic soundscape for the listener to set the tone to reflect.”

In that respect, he succeeded. “Zollie’s Retreat” is a mournful tune about the death of a Confederate general in battle not far from the border between Kentucky and Tennessee. The sprightly “Squirrel Hunter” is a crystal clear reminder that many old-time Appalachian songs are direct melodic descendants of traditional music from the British Isles. Similarly, the roots of “Camp Chase” extend back to the Civil War and Irish reels, and “Jenny Lynn” is an ancient and irresistible dancefloor banger. If it’s technical wizardry or fiddle innovation you seek, Long Violent History may not be for you. But in terms of setting the scene, Childers’ choice of songs here will drop you right in among the hills and hollers of Eastern Kentucky. Porch pickin’ sessions aren’t supposed to be perfect, anyway.

The protest song: On the album’s final and title track, Childers breaks his silence—literally. The tune starts and ends by referencing Kentucky’s state song, “My Old Kentucky Home.” In between, Childers’ band ambles through a mid-paced, boom-chick-chick waltz as their leader directly addresses the ongoing movement against systemic racism and police brutality toward Black Americans, contextualizing the issues within our world of overwhelming media saturation and increasingly elusive truth. In the song’s second half, he cleverly couches his argument in a way that’s designed to evoke empathy in the listener’s mind, and specifically in the minds of his listeners, most of whom are white, many of whom live in the South, and some in the rural South. In the song’s fourth verse, he reminds those listeners of the way the world often portrays Southerners, and contrasts that with the Black experience in America:

It’s called me belligerent, it’s took me for ignorant

But it ain’t never once made me scared just to be

Could you imagine just constantly worrying

Kicking and fighting, begging to breathe?

With that framework established, Childers flips the script, imagining a scenario in which authorities came to the Appalachian mountains and started brutalizing and killing local folks. Whether it will change any minds may never be known, but it’s an undeniably effective technique from a master songwriter:

How many boys could they haul off this mountain

Shoot full of holes, cuffed and layin’ in the streets

‘Til we come into town in a stark ravin’ anger

Looking for answers and armed to the teeth?

Thirty-ought-sixes, Papaw’s old pistol

How many, you reckon, would it be, four or five?

The video: Though not a part of the album proper, Childers’ video introduction to Long Violent History may be the most striking thing he released on Sept. 18. It’s a modest production, with Childers sitting on a stool against a gray background, looking not completely comfortable, but resolute as he delivers his message. Which is, more or less: Black lives matter, and if you disagree with that simple statement, or you don’t understand the roots of this year’s unrest, or you oppose the movement as a whole, it’s time for self-reflection.

“In the midst of our own daily struggles, it’s often hard to share an understanding for what another person might be going through,” Childers says, looking directly into the camera. “With that in mind, at the risk of mistakenly analogizing two groups of people, I would ask my white, rural listeners to think on this. I don’t mean to imply that many of you aren’t already doing good self-examination on this issue, but I have heard from many who have not.”

He goes on to parallel the scenario from “Long Violent History,” conjuring up imaginary headlines about violence against Appalachians by public servants. “I’d venture to say if we were met with this type of daily attack on our own people,” he says, “we would take action in a way that hasn’t been seen since the Battle of Blair Mountain in West Virginia.”

The Battle of Blair Mountain, as you may or may not know, was a 1921 armed labor uprising by coal miners in deep southwestern West Virginia. The man knows how to speak to his people.

That’s what’s so interesting about this entire project. It’s not the surprise release or the fiddle playing or maybe even the message, but the messenger himself. If you listen to Childers’ music, it’s clear as day that he, first and foremost, identifies as an Appalachian. You can hear it in his lyrical references to Big Sandy and the Sludge River, to mason jars of moonshine, to tanning fox hides and running the pitch-black roads that spider-web across the region. You can hear it in his thick accent, and when he speeds through his between-song banter at shows. And you can hear it in the anger that simmers in his voice in the video introduction to Long Violent History, when he talks about uncaring people in power, untrustable news reports, unheeded struggles among this country’s poorest populations, and the unjust treatment of countless Black Americans, including Breonna Taylor—“a Kentuckian like me,” he says, biting off every word.

It doesn’t take a degree in music marketing to recognize that Childers is likely to lose (and gain) some fans as a result of this project. You can just check his mentions on Twitter and it’s clear he already has. So it’s not just anger bubbling under his voice in that video. There’s almost certainly a little bit of fear in there, and a whole lot of guts, and some discomfort from a guy who usually lets his songs do the talking. Long Violent History is not Tyler Childers’ best album, but by telling us a lot more about the man than we knew before, it’s definitely his bravest. And right now, brave is what we need.

Ben Salmon is a committed night owl with an undying devotion to discovering new music. He lives in the great state of Oregon, where he hosts a killer radio show and obsesses about Kentucky basketball from afar. Ben has been writing about music for more than two decades, sometimes for websites you’ve heard of but more often for alt-weekly papers in cities across the country. Follow him on Twitter at @bcsalmon.