On an airplane, Don Henley told Randy Newman he couldn’t charter Learjets anymore. “Too expensive” was his reasoning. “Jesus, that’s tough,” Newman said back, sarcastically. “You can’t live on $1,000,000 a year anymore.” Still in the air, Henley suggested to Newman: “Everybody’s writing L.A. songs, people not from here. You’re from here. Why don’t you write one?” Newman took the Eagles drummer’s recommendation to heart, jetting off to Warner Bros. Recording Studio in Hollywood to bang out a smash—the thrilling, synthesized “I Love L.A.,” in which he, David Paich, Nathan East, Lenny Castro, Christine McVie, and Lindsey Buckingham yell, “We love it!” while Steve Lukather goes absolutely mental on the axe. I hear “I Love L.A.” every time the Dodgers win, because it’s become Los Angeles’ unofficial anthem—a motto written on alley walls and movie theater marquees from the Valley to the Santa Monica Pier. The only problem is: “I Love L.A.” is not the happy-go-lucky, Beach Boys-adoring paean that Angelenos have deemed it to be. It’s about disillusioned living, in a place where the sun is always shining and the women are always beautiful. But don’t look at that homeless person. Check out those palm trees instead! And that’s a Randy Newman record for ya: sardonic contradictions aplenty, all figured beneath colossally stellar pop symphonies.

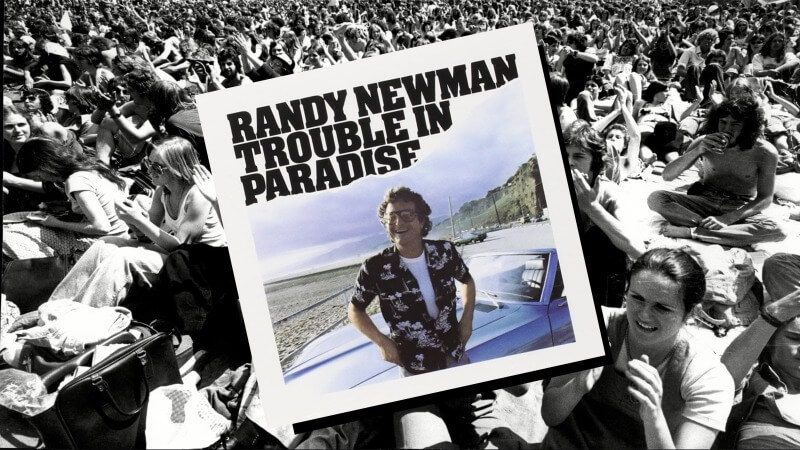

Trouble in Paradise was the piano stalwart’s seventh album, released at the end of a wonderful 11-year run that featured Sail Away, Good Old Boys, and Little Criminals. For a decade, Newman sang about burning rivers, intolerant Southerners, and vertically-challenged folk, making a name for himself as rock and roll’s funny guy—like Loudon Wainwright III but in a Billy Joel getup! But Newman wasn’t just funny. He was well-respected and brainy; his musical sarcasm teetered on impoliteness; and his albums illustrated a detailed and exhaustive talent for songcraft. Ry Cooder, Jim Keltner, the Eagles, Paul Simon, Fleetwood Mac, Linda Ronstadt, Bob Seger, and Rickie Lee Jones played on his records, for Christ’s sake. He was a bonafide songwriter extraordinaire, doling out ear candy like he was the king of adult contemporary radio. Trouble in Paradise gets pulled in two directions, tugged on by pop perfection and satirical risks. The songs are anything but subtle, taking on unreliable narrators with twisted and fascinating perspectives on racism, sex, drugs, and fame. And, better-sounding than its predecessor Born Again, Trouble in Paradise is not just an excellently produced (thanks to co-conspirator Russ Titelman and longtime friend Lenny Waronker) and deeply tragic and sensitive wash of songs, but Newman’s best project of the ’80s altogether.

Ralph Grierson’s piano wanders into “Same Girl,” Newman’s bare-naked portrait of a woman hooked on heroin (“A few more nights on the street, that’s all. A few more holes in your arm. A few more years with me, that’s all”). It sounds like a ballet, gentler than the glaringly electronic “Mikey’s,” Newman’s study of a macho-wacho, shitheel grump who can’t stand the “ugly music” playing all the time in his favorite bar. “Whatever happened to the old songs, Mikey?” he shouts, just after bemoaning the “new” Mexican and Chinese patrons and workers around him. “Like the ‘Duke of Earl.’ Mikey, whatever happened to the fucking ‘Duke of Earl’?” I dig that Newman sings about a crank on one of his more elaborately experimental tracks.

Newman amps up the pitied blues on ballroom-rocker “There’s a Party At My House,” caroling and grooving and rapping about a woman’s chest. “I’m Different” is, lyrically, Newman’s tamest effort on Trouble in Paradise (“I’m different and that’s how it goes, ain’t gonna play your game”), but the song sweeps and swoons, thanks to the vocal trio of Jennifer Warnes, Wendy Waldman, and Linda Ronstadt. In his oo-wee-oo duet with Simon (“The Blues”), Newman winks at us, hunches over his synthesizer, and argues that getting dumped by a girl is as traumatizing as watching your best friend die in a bar fight. “Christmas in Cape Town” is an ugly affair about a miserable Afrikaner during apartheid, as Newman ventriloquises a racist by tossing around epithets and telling a visiting English girl to “go back to your own miserable country.” I’ve always wondered if Newman ever got exhausted by his own enterprise. I mean, how does someone so willingly spend 50 years of his life giving voices to people who deserve to remain voiceless? I suppose it takes a lot of love for your craft to enter such desperate and delusional imaginations.

He and his band uncork on “My Life is Good,” especially when Lukather’s guitar screeches and squirms while the song’s narrator—a bullish, status-obsessed halfwit—and his wife pick up an undocumented housekeeper in Mexico, send their aggressive, misbehaved child to a private Beverly Hills school, and do cocaine with shit-hot businessmen in-town from New York City. When our self-aggrandizing tour guide makes his way to the Bel-Air Hotel to pay Bruce Springsteen a visit, the piano picks up and David Paich’s organ swirls. “He said, ‘Rand, I’m tired. How would you like to be The Boss for a while?’ Well, yeah! Blow, Big Man, blow!” Cue a curled, bewitching saxophone à la Clarence Clemons. Newman isn’t afraid of contrasts on the not-so-charitable “Miami” either, regaling us with Hawaiian-shirted vignettes of “impure women,” the “best dope in the world” (and it’s free!), very bad men from Argentina, and a “double-jointed guy with the circus in St. Pete.”

But Trouble in Paradise’s finest moments come during its second half, when Newman steps into himself on the acerbic and personal “Take Me Back,” singing about growing up in North Hollywood in his parents’ “steamy little bungalow.” His nostalgia coasts on a bed of sighing, plushy organ, horns supplied by Larry Williams, Steve Madaio, and Ernie Watts, and Don Henley and Bob Seger’s excitable backing chants. On “Song for the Dead,” Newman doesn’t even bother coming up with a punchline or covert metaphor. Under the guise of a soldier burying dead bodies on a battle field, he makes excuses for an ongoing Vietnam War—the war that put those men in the ground to begin with: “We’d like to express our deep admiration for your courage under fire, and your willingness to die for your country, boys. We won’t forget.” It’s just him, a piano, and not much else—a stark, necessary conclusion to a project dramatically fueled by its maker’s appetite for timely, bombastic pop flavor.

Recently at a Florida antique store, I picked up a destroyed VHS copy of Toy Story. It looked just like the one I’d kept on my father’s dresser for the first six years of my life. But I opened the package, saw mold collecting on the reels, and decided to leave the tape behind. Still, I couldn’t get “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” out of my head after. And then it dawned on me: the only people I’ve known longer than Randy Newman are my parents. I use “known” in a figurative sense, of course, but now, 20-plus years after meeting him in the Toy Story credits for the first time, I’m running into the types of people Newman sings about on Trouble in Paradise. Talk about an untouchable curation of outrageously recognizable and oft-unbearable faces. Imagination inevitably turns into horribleness, and then, when you’re old enough, you learn to combine the two. The Pixar songs are always good and worth it, but Randy Newman is simply peerless when his unhappiness finds terrific company in the cynical, smart-aleck debauchery of miserable nobodies. Can you imagine if he’d stuck to just writing love songs?

Listen to Randy Newman perform at The Odeon on August 10, 1983 below.