Naturally, if your chosen band moniker happens to be The Vaccines, timing is everything when you’re trying to schedule your latest album release during a dark, harrowing pandemic. Only Danny O’Reilly’s Celtic combo The Coronas might have had to face more hurdles in the public-sensitivity department. Appear on the pop-cultural radar before the actual Pfizer and Moderna anti-Covid shots are ready, and you look like gauche opportunists; too late and you’re grasping at vanishing coattails. But either way, it became obvious that both panaceas were sorely needed as 2020 wore on. And just as the actual hypodermic jabs were ready, word leaked out that Back in Love City, The Vaccines’ stunning new fifth outing, was in the pipeline, too. And it may not cure everything that ails you, but it stands as a timely little reminder that great music—especially in a time of grave despair—can truly save your life.

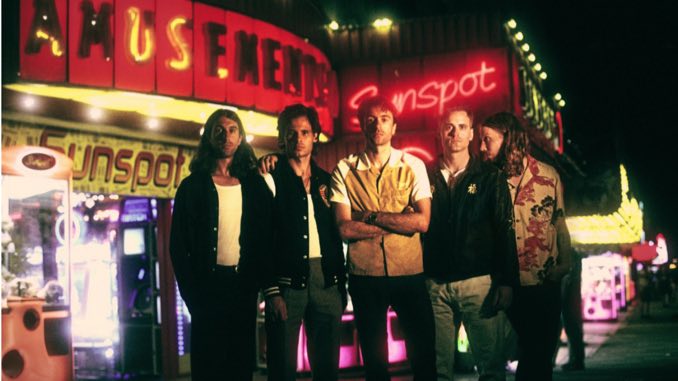

It seemed like an eternity since 2018’s Combat Sports had come out. And the more you heard about the worldwide search for vaccines in coronavirus news, the more you thought about the band itself—where were they? What were they up to? Had they seized the lockdown day and penned a slew of patently cynical, pun-peppered pop-punk anthems, a la their definitive 2001 debut What Did You Expect From The Vaccines? Or was something far creepier going on? A bit of both, it turns out. Singer/songwriter Justin Young and company (guitarist Freddie Cowan, keyboardist Tim Lanham—no relation—bassist Arni Arnason, drummer Yoann Intonti) had actually completed work on Back in Love City pre-lockdown, recording with keen-eared producer Daniel Ledinsky at the Sonic Ranch residential studio outside El Paso, Texas. “So we had a finished record when the pandemic hit, and the plan had always been to actually sit on it for a while and think about the creative side and think about the visuals, and how we wanted to create this world around it,” says Young. “So we had always planned to wait a whole year to release it, so not much changed for us, other than that we ended up having to wait a lot longer.”

Instead, they spent 2020 celebrating the 10th anniversary of What Did You Expect From The Vaccines? with a special demo version of the disc, which stands as a wonderfully scratchy, equally energetic template of their entire philosophy. In these careening, less-polished takes of future hit singles like “Norgaard,” “If You Wanna” and “Post Break Up Sex,” the energy is there, glaringly obvious, and sparking like like a live third rail. And it was a concept so deceptively simple that it was dumbfounding that no one had arrived at it before them: Young, a failed troubadour from Britain’s Mumford & Sons neo-folk movement, teamed up with the equally frustrated post-Strokes punk guitarist Freddie Cowan, and like that old “You got peanut butter in my chocolate!”/“But you got chocolate in my peanut butter!” Reese’s commercial, the former’s warm vocals and clever composing skills blended seamlessly with the latter’s buzzy, hornet-in-a-jar power chords, until the two actually seemed to converse with each other on every song, with the shapeshifting Cowan changing tones to complement every track differently. The Vaccines were probably the first band since R.E.M. to achieve that rare distinction.

Young swears that he’d almost forgotten how brash and swaggering The Vaccines had appeared on their debut until he dug up those demos and started listening to the original 14 tracks again—a dozen slated for the album and two great B-sides, “We’re Happening” and “Somebody Else’s Child.” And even without the final blistering electric solo on this acoustic version of the minute-long classic “Wreckin’ Bar,” their unique vocal-vs.-six-string oomph is present, and foreshadows all the remarkable music to come. No one sounded quite like The Vaccines back then, or now; Their future, if they could maintain such high artistic quality from album to album, was instantly assured. “So we released the demos because we thought it would be a nice thing for some people to hear,” Young says. “And it was nice for us, as well, because I really hadn’t listened to a lot of that stuff for 10 years, and the longer it goes on, the more it continues to essentially lay the foundations for our career. And the fact that I’m sitting here now, talking to you after 10 years and you still give a shit?” He sighs, contentedly. “I feel increasingly appreciative and proud of it, and I love that record now. I was very insecure and kind of nervous and edgy when it came out, so it was difficult, seeing everything that everyone said about it, and it made it hard to love. But I am very proud of it now.”

None of this, of course, can adequately prepare you for the streamlined sonic sheen and general earworm genius of Love City. Like Vampire Weekend’s similarly complex and painstakingly constructed Modern Vampires of the City Grammy winner, it’s so intricately plotted that they should teach an entire college course on how to scientifically parse it. And Cowan matches Young, blow for blow, on every boundary-pushing number, starting with the opening title track, which puts a sinister spy-movie-guitar spin on “Mr. Blue Sky”-ish ELO vocoder plaints, as Young spits out reams of ultra-snarky couplets that set up the album’s loose dystopian-future theme: “Seven years sober, couldn’t give you up for Lent / So I never even questioned if your cookies had consent.” His wordplay just gets sharper, more eviscerating from there; two cuts in, he’s juggling more modern allusions in the crackly, twin-chorused “Headphones Baby,” with “Can’t pop the question if you’re live on Reddit / Until your father’s back on carbon credit.” Beneath his confident style of blurt-crooning these observations, there’s a surreal stream-of-consciousness quality to what he’s singing that borders on the James Thurber absurd.

And at this point, Cowan instinctively understands how to best complement his vocalist’s shifting moods, getting Morricone-booming on “Wanderlust,” letting his Ventures surf side simmer in “Paranormal Romance,” going full Sabbath-growling tilt on the propulsive “People’s Republic of Desire,” then reining the angst in for a straight-face acoustic tribute to America called “Heart Land,” wherein Young forgives us our knuckleheaded trespasses by charmingly equating the States with “milk shake and fries,” “warm apple pies” and “king-size Coke with lots of ice.” “I’m not giving up on my love for you, America,” he warmly assures us, in one of rock’s most charismatic voices, still strong after some scary throat surgeries a few years ago. But just when you think you’re comprehending the new Vaccines direction, they pull the rug out with the punk-manic barnstormer “Jump Off the Top,” in which Cowan actually manages to one-up his succinct “Wreckin’ Bar” lead with an arpeggiated bridge that feels downright demonically possessed. Rock bands just don’t come any more inspiring than this these days, and they just keep getting better and better. Back In Love City is a standout album on its own merits, and not many groups can offer illuminating before and after pictures of their growth with two back-to-back releases. Trailblazers like The Vaccines can quite possibly keep you alive through the coronavirus era, along with those requisite shots, of course. Young had more to share with Paste on all of the above.

Paste: Jumping forward, have you written any new songs?

Justin Young: Yeah. Lots of new songs. I actually have a folder on my computer with the last 25 or 30 songs for whatever follows this record, and I wouldn’t say that they’re necessarily lighter or darker as a result of, or a response to, what happened. But one thing I’ve spoken a lot about with friends who write songs and make music and create art, more generally, is that I think this last year, it’s been very difficult to stay inspired. I mean, it’s life, and you can separate between motivation and inspiration in a sense, but it’s very difficult, because normally you’re kind of traveling to the edges of life’s extremes, and you’re drawing on that for inspiration. And in not being able to live life, I think the world is kind of drying up for me, lyrically, as well as a few people I’ve spoken to. So you have to be figuring out new ways to find that inspiration from somewhere. But I will say—because we pushed the album release back when the pandemic hit—as it has done everything, it definitely reframed the record. And on the odd occasion that I listen back to Back in Love City now, I am sort of struck by how the last 18 months have given it new meaning. But I suppose you can probably find that new meaning in pretty much anything, can’t you?

Paste: Every time we’ve talked, you never could make a relationship work. Do you have a significant other yet?

Young: Actually, I do! My girlfriend moved in with me just a week before Covid, before lockdown. And so we were placed into this, uh, quite intense situation together. But not only did we survive, but I would like to say we thrived in it. It was a baptism by fire, and it was amazing. I genuinely feel so lucky to have been locked up with someone who I loved and who loved me, because I know plenty of people who were alone. And we were here together for the whole time in London, and we also met in London, actually, met at a party. And I’m in London now, too.

Paste: You namecheck all sorts of technology here. And not in a good way.

Young: Pre-Covid and post-Covid, I would quite often find myself at lunch, with four friends and realize that we were all just kind of playing on our phones. And I suppose in a way, it makes sense, though, because one of the things that I thought a lot about during the last year was was that so much life—and I know people always say that you’ve gotta live in the moment—I actually think that our obsession with being on our phones, even when we’re around people that we love, is an extension of that. Because actually, the thing that I found tough about Covid was not having anything to look forward to. And that’s what life is about, really, right? You’re just constantly looking forward to the next thing, and I think that having a phone in our pockets or in our hands all the time just magnifies the fact that—whilst we’re happy, sitting in a nice restaurant, eating lunch with our friends—a little part of us is constantly wondering where we’re gonna go next, and who we’re gonna go with.

Paste: You really make it difficult for yourself, writing this Bob Dylan flurry of lyrics, which you then have to sing, word for word, in concert every night. Do you ever forget passages and just kind of hum your way through?

Young: Well, I suppose it’s like muscle memory, right? So the second that you start really thinking about them, then you kind of trip up and forget them all. But I’ve not yet become the “sad rocker with lyrics on a teleprompter.” But hopefully one day that will come! So they are a kind of muscle memory. But half the time I’m leaving the house, I forget my keys, so it’s increasingly amazing to me that I don’t forget lyrics. But I suppose that they’re just deeply ingrained, aren’t they?

Paste: You even managed to sneak the word “thesaurus” into “Headphones Baby.” Do you use one?

Young: Oh, I do! Absolutely. Absolutely. Gone are the days of stream of consciousness at the end of my bed with no visual aid, hoping that whatever I’m looking for will come to me. So I use whatever I can, whatever’s around me. And actually, you can’t see me right now, but I have wall upon wall of books in my house, and I use a lot of them for reference, when I’m just looking for a certain word. And I try not to lean on any one thing too heavily, because … well, I just picked up a book called Other Men’s Flowers, and it’s a poetry anthology, compiled by someone’s grandfather, I think. But if I find that the title’s appealing to me, then I’ll open it up and skim through.

Paste: Your verses on “Jump Off the Top” are kind of neener-neener taunting.

Young: I’m glad you picked on that melody, because I always describe it as “Nyah, nah-nah, nyah nah!”

Paste: In “Paranormal Romance,” like a lot of pandemic folks, you seem to be looking skyward.

Young: Well, I definitely found myself looking upwards. And maybe this is a trap that men making music often fall into as they enter their 30s, but I found that a lot of the songs were kind of interstellar in subject matter, as opposed to insular. And I used to think that I experienced paranormal stuff, but I’ve become a bit of a cynic in recent years. So I’m not sure where I place a lot of that stuff anymore.

Paste: Your mention in “Heart Land” of America’s “king-size Coke with lots of ice” reminds me that they actually did a scientific study of why McDonald’s Coca-Cola tasted so much better, and they decided that the straw itself had a lot to do with it.

Young: Is that so? So the soda fountain is a good source, absolutely—there’s a whole hierarchy of Coke, the lowest of the low being a small plastic bottle of Coke—it’s horrible. But I love a good glass bottle, and obviously, Mexican Coke is a whole other level. And I do love America, and my relationship with America is ever-changing. You remember I lived in New York for a couple of years, and I came over and stayed a couple of months in L.A. every year, and I love it. And from my earliest memories , my whole understanding of popular culture was viewed through the lens of American movies and American culture. And it still blows my mind that I’ll be in some random city in the Midwest, and I’ll be like, “Oh, my God! That’s where that movie was set!” Or, “That street was in that film!” So I guess I’ve just been in love with the idea of America, kind of like this gift-wrapped version of America that it gives out to the world. And so that song is through the eyes of a British teenager more than anything—it’s knowingly naive and knowingly simplistic.

Paste: The closing waltz “Pink Water Pistols” sounds snatched from an old ’60s musical, with Duane Eddy on guitar.

Young: And I’m very proud of the lyrics on that song, actually, because that’s a very personal, personally reflective song. And a lot of the lyrics came first on that song, as they did on a lot of the songs on this record. Which was the first time that that ever really happened on a Vaccines record—normally the melody would come, and then the lyrics would either come with the melody, or after the melody. But for a lot of this record, I just had pages and pages of … not like poems, but I guess just like prose, things that I just thought were funny or interesting couplets.

Paste: And in that song you sing, “I’ve been working on my mind / Interior design.” But it’s not cool in Britain to admit to seeing a therapist, right?

Young: Yeah, definitely. But I’ve been seeing someone on a weekly basis for years, and I feel very privileged, of course, because not everybody has the resources available to do that. So I have been kind of looking inwards and trying to … I dunno. I guess chip away and refine that mess of a mind that’s in there, and try and be a better man and take some responsibility. So I think it’s a great thing, but I suppose the lyrics in that song are fairly self-explanatory, without being too literary.

Paste: In the sinister stomper “Bandit,” my brother from another mother, Tim Lanham, really comes into his own as your official keyboardist.

Young: Yes. And “Bandit,” I guess, is really just about having a broken heart, I suppose. And with Tim and Yoann, it was the first time that they were involved from the record’s inception point. On the last record, they weren’t around for the first half of the session, and then they joined the band halfway through. So this was the first time, I think, where they felt like they really had skin in the game. And as a result of that, we really got them at their best. But then also, I think it just was—by its nature and the way we made it—a very collaborative record. It was a very free and open environment, and people were encouraged to try everything all the time, which was great fun and very fulfilling. But it just means that there’s a lot of everybody on it, which is great, I think.

Paste: And “Headphones” gives you not one, but two singalong choruses. As the early flagship single, it was reason to rejoice.

Young: Thanks, man! Yeah, I love that song. And it’s funny—there’s definitely a section of our fans that were slightly freaked, thinking that the record was gonna be this super-pop expedition or whatever. But I tried to reassure them as best I could that it’s a really well-rounded affair. But I am very proud of that song, and yeah, I think we are getting better, as most artists do. But that’s reason enough to carry on, isn’t it? We still absolutely love it, and I think we’re still finding out what we’re doing. And every time we make a record, I get to the end of it and think, “I reckon we’ve got another one in us, and I reckon we can do even better next time.” And that’s reason enough to keep going, I think. But one thing I will say is that I think that The Vaccines, at our core, ever since we started, has this very simple, identifiable DNA. So if I were to go on a journey, or a search, for what makes The Vaccines great, I think that it’s our own willingness to not really acknowledge what it is that makes us great, even when it’s staring us right in the face. And I kept thinking, “What should The Vaccines sound like in 2021?” And I really do believe that it’s the band that you hear on Back in Love City.