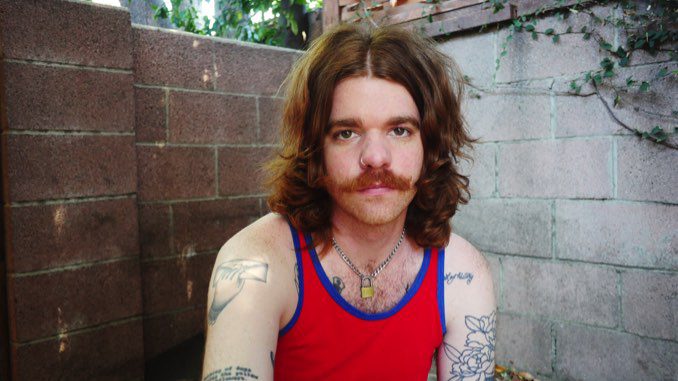

Somewhere in Los Angeles, there’s a denim-clad, tattooed floral prince parading the streets with a black boombox. His name is Kevin Patrick Sullivan, but you probably know him as Field Medic, the prolific freak-folk virtuoso who put out his first record in 2013, but made tall waves in 2017 with a compilation called Songs from the Sunroom and was the source of a (momentarily) viral TikTok audio clip in 2021. Don’t get it twisted, though: Sullivan is so much more than the 40-second “song i made up to stop myself from having a panic attack just now” that consumed social media a year ago. He writes haikus, used to sport a gorgeous chipped tooth, turns his stage name into death metal merch and is a longtime thrift god. In 2016, he teased a 2023 album, Dope Girl Chronicles, and intends to deliver on that promise next year.

As a Gen Z kid trying to navigate the harsh discomforts of a life that’s endlessly underneath the microscope of social media and strained by social distancing, I hold Sullivan’s work close. When I was carsick and stuck in the very back of an Enterprise van with six other dudes in Northern Washington, I listened to “Mood Ring Baby” on repeat as we wound around the sharp, never-ending elbows of the Cascades. His song “OTL” held court as a romantic anthem that soundtracked a past long-term relationship. A matchbook that was stuffed in my copy of Fade Into the Dawn forever rests in a memento box on the living room shelf. His voice coasts along in a smooth, basement-show gloam; his songs are self-reflective and weigh in on sobriety, anxiety, lost love and personal faults. Both urgent and generous, Field Medic is an artist we need now more than ever.

It’s been two years since we’ve heard from Sullivan in a full-length capacity. His last record, Floral Prince, didn’t arrive like a conceptual project—because it wasn’t. Thematically, it was cohesive, but a lot of the songs, like “-h-o-u-s-e-k-e-y-z-” and “i want you so bad it hurts,” were born a long time before 2020. (“-h-o-u-s-e-k-e-y-z-,” specifically, is over eight years old.) But Sullivan’s output is teeming, as he’s compiled dozens of releases, some big, some small, over a six- or seven-year period. As a result, Floral Prince sounded like a mixtape, properly mirroring the architecture of an artist who puts out new music, in one form or another, every other month. “I do think that, when you just drop songs out of nowhere, it’s easy to get swallowed up by the million other songs dropping at the same time,” Sullivan says.

The reason there are more Field Medic re-releases and one-offs than album-exclusive material is because Sullivan rarely writes in an album mindset. “I’m sporadic with the way that I tend to create songs,” he says. “I think that the reason they wind up on albums, sometimes, is simply because I didn’t leak them.” There’s an assurance in leaking a song your fans have heard already, and Sullivan knows that something isn’t inherently finished forever just because it’s on the internet. The Field Medic archive often presents itself as one big edit button. “[The new songs] take this different shape, whereas the songs that I’ve made several times or keep releasing, there’s a certain level of safety,” he adds. “It’s always scarier to drop a fresh, unheard track than being like, ‘I’m going to re-record “-h-o-u-s-e-k-e-y-z-” again because that’s a song I wrote so long ago and just road-tested.’”

After releasing the six-song project Plunge Deep Golden Knife, Sullivan went relatively quiet in order to focus on his next full-length. Since he harbors a workaholic creative mind that’s brimming with compulsive tendencies, slowing down wasn’t easy for Sullivan to do—making music is an essential part of his own healing, and sharing his work is a gesture he finds joy in making. “I think it’s, honestly, some form of an addiction. I find that, in songwriting or poetry or whatever it is, that’s the one world that I can control,” he says. “Also, the tactile element of making music has always been helpful for me to calm down when I’m feeling anxious or, at the worst, having some sort of panic attack. That’s how the panic attack song came about. When I’m that deep in it, I’ll just start singing something to myself because it calms my nerves.”

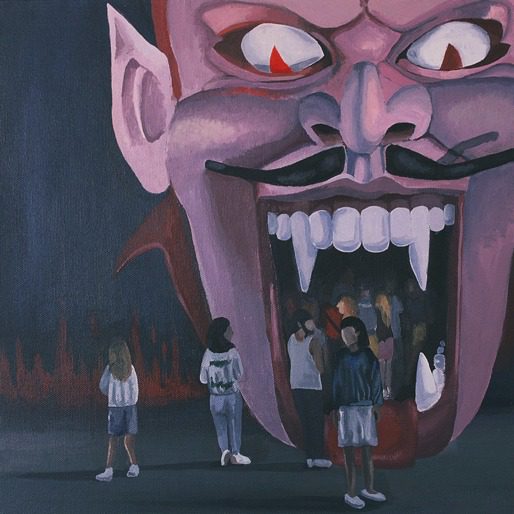

On his fourth release through Run For Cover Records, grow your hair long if you’re wanting to see something that you can change, Sullivan isn’t just leaning into Fiona Apple-length album titles—he’s also traded in his signature boombox for an assemblage of fully realized arrangements. The world of Field Medic, at least for now, is no longer just an acoustic guitar and a lo-fi drum loop. “I’ve always been curious about making a more ‘band-type’ album,” Sullivan says. “I think I was at a certain point in my life, when I began writing these songs, where I was finally ready to relinquish control a little bit.”

Sullivan estimates that 85% of Field Medic releases are recorded live, which left him with a superstition about multi-tracking, that he couldn’t do a good vocal take unless he was simultaneously playing. But in the first leg of the pandemic, he began making rap songs and experimenting with his computer, and eventually decided he was ready to give, as he puts it, making an “HD” record with outside musicians a shot. The first song he made was “Always Emptiness,” and it quickly became evident that grow your hair long had a kind of potential Sullivan hadn’t yet encountered in his work. “When I heard that with the drums and the pedal steel and the cool guitar line, it made me feel really excited about the music, because I’ve never heard something that dynamic or lush around my songwriting before,” he recalls.

Much like 2019’s Fade Into the Dawn, the songs on Grow Your Hair Long were mostly written together at the same time, which provides a conceptual and sonic template throughout. The only outlier, “Weekends,” was written while Sullivan was making Fade Into the Dawn, but he never finished it. It’s inclusion is due to, as Sullivan puts it, wanting “at least one more feel-good song” on the tracklist. Though the textural throughline is present, Sullivan reveals that the secret to the record’s cohesiveness might be because the songs all use the same chords. “When we have band practice, I’m like, ‘Dude, I don’t know which order the chords should be in for this song, because they’re all the same,’” he says, laughing. “Maybe that’s the secret glue, that they’re all just really the same song.”

Sullivan recorded grow your hair long with multi-instrumentalist Gabe Goodman, pedal steel guitarist Nick Levine (currently of folk project Jodi and formerly of language-arts rock outfit Pinegrove) and drummer Nate Lich at Goodman’s L.A. studio. The influence from those players hits quickly, as opener “Always Emptiness” announces itself as Sullivan’s most fully realized song yet. In contrast, Fade Into the Dawn’s tracks had a lo-fi quality to them, an aesthetic he didn’t bring into 2022. “It’s nice to have people that are very good musicians complement the songs that I make, because I make my songs from an emotional place, like an outburst or a mantra or something,” Sullivan says. “And when I began writing this album, I started recording some of these songs by myself and my brain went blank trying to figure out how to fill them out.”

The album begins with Levine’s gorgeous, meandering pedal steel backing Sullivan, as he sings, “I wanna fall off the face of the Earth / And probably die / I tried laughing it off / But I’m gonna cry,” on “Always Emptiness.” The song is a moving testimony about defining ourselves by vices, how drinking and sobriety are a double-edged sword, each with their own debilitating side effects. Though the opening lyrics sound hyperbolic, Sullivan delivers them in earnest. “I meant it when I said it, but it’s helpful for me to look back humorously at that moment, that I really felt that way,” he says. “I just like to let it out, like I have to. The songs, to me, are just a vessel for my thoughts.”

To listen to a Field Medic record is to do yourself a certain kindness. Few artists working are as candid about their own personal metamorphoses as Sullivan. Through his own depictions of sobriety, love and masculinity, his confessionals take shape as spare shoulders for his listeners who might be enduring similar bouts. These themes arise often, but never redundantly. Sullivan always has something new to say, commentary on new perspectives of the world that surrounds him. The jealousy in “Henna Tattoo” is not the same jealousy in “I Had a Dream That You Died,” but the stems we see come from the same place in Sullivan’s ever-changing heart. “The simple answer is that I’m still learning,” he says. “I keep accidentally making the same mistakes over and over again, and then I have to find new ways to work out how it’s disrupted my life in that present moment.”

Sullivan’s relationship to vulnerability exists because it’s the main function of music for him. He cites the Nick Drake lyric, “If songs were lines in a conversation, the situation would be fine,” from “Hazey Jane 2” as a mantra that’s stuck with him through his ongoing battle with mental illness. “It’s really difficult for me to speak up, sometimes, even in a completely inconsequential situation,” Sullivan says. “If I want to move to a different table at a restaurant, I’m shy about asking the waiter. But, for some reason, it’s always been natural for me to just let out my deepest, darkest thoughts in songwriting.” The songs aren’t therapy as much as they are a holistic healing practice, translations of inner monologues that help Sullivan navigate these momentary heavy feelings and dark thoughts. “It’s not like you write the song and then feel all the way better, but it’s almost like a deep breath to just say it, especially with this record. It’s hella dark, super bummer vibes,” he says.

Though Sullivan conjures transgressive personal imagery in his work, like, “I look back so much it’s hurting my neck / ‘Cuz the truth is too absurd to accept,” or “I lost my passion and my looks / My stomach’s turning like a brook,” he believes that music could be what keeps him away from the edge. “I have a lyric in some unreleased rap song that’s like, ‘I just think that every song I make could save my life,’ so I started to just obsess over making songs and feeling like, ‘This is what’s going to make me happy and that it’s what’s going to save my life,’ even though that’s kind of a bold statement,” Sullivan says. At his worst, he loses himself to his own ideas, and the song-making teeters on becoming an unhealthy obsession. But he’s at a place now where self-care is getting just as much recognition in his headspace as sadness. “I will say, my only other tried-and-true method of coping is binge-drinking,” he admits. “So I think that songwriting is a little bit better in that regard. I’m trying to be more conscious about taking time for myself just as a person and not as a moniker or mascot, or something, just taking bike rides and being a human, not a song.”

It does not take much to fall in love with a Field Medic song. They’re often so familiar and abundant with humor, but not oversaturated with self-deprecation. As long as Sullivan is making music, there is the hope you have, as a listener, that he’s doing okay. It’s not a parasocial relationship to always want your heroes to be okay. After Floral Prince came out, he had a long stretch of sobriety that was wiped out after a few days on tour in 2021. “I thought that I was a changed man and I was on a path to righteousness,” Sullivan recalls. “I had so much anxiety and I took a sip. That led me into this spiral of confusion and going in and out of a dark place.”

Sometimes popular music romanticizes the act of getting better, as if walking the complicated and uneven road to sobriety and properly dosed medication is a danceable melody. When you’re in close proximity to addiction, it’s easy to imagine an idyllic version of what’s right in front of you. It’s just a human condition to try to convince oneself an alcoholic family member or depressed friend is anything but. It’s difficult to unlearn, because we are taught from birth to see our loved ones in a certain unshakable light. Something in that is toxic, but it goes back too many generations to simply erase overnight.

Sullivan’s music tries to unspool the seemingly endless presentation of delusional perfection our forefathers have left within us. grow your hair long speaks to the parts of ourselves that are so often left in the margins, the pieces of us that want to get better but often struggle to even make the first step. That’s what makes this record—despite the wagon leaving him behind, or the suicidal ideation he flirts with—Sullivan’s most hopeful. In our conversation, he talks affirmingly about how he’s no longer in the record’s headspace. “I already am, on some level, now just looking back and being like, ‘Man, that was a hella dark zone I was in,’” he says. “I’m happy that I’m no longer in that zone, but I’m also grateful that I still decided to write through the pain and make an album. There were points where I felt so ambivalent and brain-dead from what was going through my head that I wasn’t sure I could even play guitar or sing.”

That dark zone isn’t necessarily gone forever, but, for now, it’s in Sullivan’s rearview. There are castles in the air on grow your hair long that he’s never fully walked into before. On “Miracle/Marigold,” Sullivan sings, “I guess I’ve got no choice but to keep flexing through the pain / I hope this is just a funny story to tell one day.” He’s not winking or feeding us a line. No, instead, he’s trying to have some optimism in the most Field Medic way possible. A lyric I come back to arrives on “I Had a Dream That You Died,” when he sings, “I had a dream that I saw / A blue whale, I was happy.” Stage names and monikers be damned, because this world we live in is cruel and these bodies of ours are unrelenting. Joy is fleeting, and we must remember to make time for ourselves, come up for air and catch a glimpse of something wondrous before tumbling back down.

Matt Mitchell is a writer living in Columbus, Ohio. His writing can be found now, or soon, in Pitchfork, Bandcamp, Paste, LitHub and elsewhere. Find him on Twitter @matt_mitchell48.

Revisit Field Medic’s 2019 Paste Studio session below.