Near the end of The Execution of All Things, Jenny Lewis delivers perhaps the most disruptive moment on an album full of them. Punctuating a sweetly sung verse about the splendor of the natural world around her, she yells out, almost as a feral bark, “It’s so fuckin’ beautiful.” It’s not just the delivery that distinguishes this moment—the sentiment is by far the bluntest expressed on the album, and just as much of its impact comes from how its pure admiration contrasts with the song’s relationship strains, which manifest even in the most idealized settings. It’s the simplest line on the record, and the most loaded behind its veneer of simplicity.

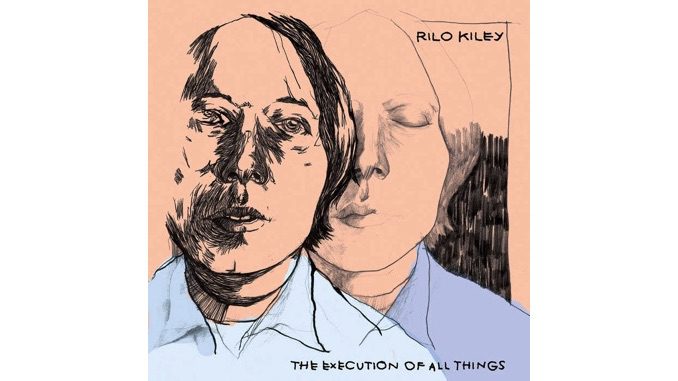

It’s this relentlessly multilayered approach that makes Rilo Kiley’s breakthrough sophomore album endure just as strongly 20 years on. Primarily creatively driven by Lewis and occasional lead vocalist Blake Sennett, Rilo Kiley cemented themselves in indie rock history upon The Execution of All Things’ arrival—it was immediately seen as a remarkable next step for the band’s sonic palette and ability to wring poignancy from vulnerability after their relatively modest debut Take Offs and Landings. But the album’s continued reverberation in a new generation of contemporary artists and listeners is arguably just as significant a part of its legacy.

From personal observation, what feels especially compelling about The Execution of All Things is how uniquely complex a record it is in terms of listener engagement. Rilo Kiley’s interconnected focal points mean that any one person can find resonance in it that another may not, but not out of a vague or shallow universality. Rather, it’s a pervasive lyrical hyperspecificity—and an understanding that no singular major life event lives in its isolated bubble—that makes every theme of the record feel just as organic and vital, peeking through in brief glimmers, yet bright enough to be fully formed. The fraying communication in failing romantic relationships interlocks with memories of parents’ divorces, while anxieties about “the disappearing ground” from climate change beget worries about one’s personal future and capacity to rebuild in the wake of devastation. Depression and frustration and witnessing addiction all feed off each other, creating a feedback loop where you feel you can never realize your capacity for good, no matter how hard you try.

The album’s opening track, fittingly, acts as a shrewd introduction to this thematic multiplicity. A steady, minimalist electronic beat counts “The Good That Won’t Come Out” in, before the twang and slides of alt-country guitar enter the fray, setting the scene as forlorn before Lewis even opens her mouth. When she does, it only compounds the melancholia evoked instrumentally. Lewis’ lyrics span from voicing personal anxiety (“I do this thing where I think I’m real sick / But I won’t go to the doctor to find out about it”), sharing distress over ecological decay (“We’re all so upset / About the disappearing ground / As we watch it melt”) and mourning those who take their own lives under the strain of it all (“Let’s talk all about our friends who lost the war”). But for as much ground as the song covers topically, it never veers from the tone it establishes in its opening moments. “The Good That Won’t Come Out” becomes both microcosm for The Execution of All Things and primer for its predominant approach—an album examining all the ways the external can seep into personal turmoil, and how self-probing can illuminate everything outside one’s own head.

The more one reads about Lewis’ own tumultuous background amid this album’s production, the easier it becomes to see how her songwriting, in all its brutal honesty, was a means for her to filter her own experiences into this nuanced portrait of disarray. The Execution of All Things came after Lewis stepped away from acting after entering the profession as a child, a decision fueled by learning that her mother had been taking the money from Jenny’s acting roles to buy and sell heroin. Sennett, too, came from a similar background as a child actor, and Rilo Kiley allowed the two a space to open up where their past work could not accommodate vulnerability on their own terms.

You can feel this in how the interpersonal fuels the conflicts at the record’s core. The climax of “Paint’s Peeling” tilts fully into the animosity coloring its early verses, creating a swirl of images where Lewis sings about choking a lover during a depressive episode. “Hail to Whatever You Found in the Sunlight That Surrounds You” hinges on a late-chorus turn where Lewis concedes, “The weather changes / Not halfway between your house and mine,” a double entendre about both the album’s themes of climate and temperament. Even Sennett contributes to this thread—his lead vocals on “So Long” detail the final moments of a long-distance relationship as time and separation get the better of it. If the way The Execution of All Things deals with others’ impact on oneself can be condensed into a single moment, however, it’s in Lewis’ most defeated lyric on the album on “The Good That Won’t Come Out”: She tearfully sings, “You say I choose sadness / That it never once has chosen me,” immediately followed up by a quiet admission, almost withdrawn, where she mutters, “Maybe you’re right.”

It’s not hard to see why an album this intimate with its songwriters’ actual struggles keeps resonating with new listeners 20 years later. In a culture that’s gradually been expanding to include more women’s voices with narratives undeniably rooted in femininity, as well as one more prone than ever to accommodate piercing, honest lyricism about issues of mental illness and trauma, revisiting The Execution of All Things often feels like seeing the roadmap to indie rock’s future fully unfurled before you. Its direct influence on the artists who followed has been frequently documented as well, from the clear sonic footprints in the work of Waxahatchee’s Katie Crutchfield and Rilo Kiley’s Saddle Creek labelmates Hop Along, to the similarly unguarded writing of Girlpool’s Harmony Tividad. Now more than ever, it’s abundantly clear how The Execution of All Things rippled out into the music that followed.

Additionally in the record’s favor is its ability to endure by virtue of its songs standing on their own as strong singular entities while also forming a cohesive, nuanced portrait of personal strife as a whole. The sequence of “The Good That Won’t Come Out” into “Paint’s Peeling” marks the clear overture, introducing the key elements of self-critique and deteriorating interpersonal relationships, respectively, while the title track feels like a grand fatalistic assessment of what’s to be done when plagued with trouble within and without—the destruction of all things dear and sacred from the “soldiers” waging the “war” to which “The Good That Won’t Come Out” alludes. “My Slumbering Heart” thrives on the album’s thematic interplay, alternating between verses about idyllic dreams and how harshly one’s reality fails to live up to that in waking hours. But the most obvious throughline comes from the recurring outro segments composing a piece called “And That’s How I Choose To Remember It.” Each iteration of this framing device focuses on a different snapshot of Lewis’ reflections as a child of divorced parents against the backdrop of melting ice caps, where the complete picture slowly forms across the distinct narrative pieces set against the same minimalist sing-song synth melody.

This conceptual structure to the record is where Rilo Kiley’s exploration of the more lasting invisible strains of collapsing romantic relationships is at its rawest, as well as where the band’s own biography feels most present. Lewis and Sennett’s own romance splintered during the production of The Execution of All Things, and their creative partnership ended after their next two albums together. Knowing this, The Execution of All Things becomes a time capsule of sorts in not only recognizing how these artists were processing their feelings about their immediate circumstances, but also in seeing how the album captures a specific approach to writing on this subject—at times bitter and vicious, but necessary to steady unrest and provide understanding to listeners experiencing the same upheaval.

Through this lens, my own attachment to The Execution of All Things feels inseparable from the circumstances that allowed me to recognize myself in it, as I imagine is the case for many others who hold it close. On my first listen during my college years, when I had few reference points for its scornful outlook toward romantic partners, or the background Lewis and Sennett were coming from, with only the record’s qualities as a piece of music landing with me. When I next revisited it per my girlfriend’s recommendation in the early days of our relationship, past the age Lewis and Sennett were during recording, the pangs of familiarity were unmistakable—in how it deals with the tangled web of emotions as bonds erode, in its unflinching depictions of the roughest lows of depressive insecurity, in how my move to the Midwest after living my life on the East Coast made me reevaluate my ties to the natural world around me for as long as it may still remain.

Beyond that initial rediscovery, The Execution of All Things has continued to serve as a crucial beacon in times of need. It was the first album I turned to for comfort as I began to navigate my own processing of my parents’ divorce. During my lowest days, its thematic arc acted as a reminder to find strength in holding onto what good the world outside me held, even when it felt like the good would never come out of me. The affirmations in the face of internal struggle on “A Better Son/Daughter” brought a sense of hope in forging on, especially in linking the song’s gendered language toward my own trials as a trans woman.

Because what The Execution of All Things thrives on—even 20 years later, long after its newness to me had worn off—is its capacity for catharsis amid defeat. It’s there from the very beginning of the record, in “The Good That Won’t Come Out” suddenly expanding from its lo-fi sound to an arresting finish that makes Lewis’ voice louder, bolder, reaching far beyond its initial understated confessions. It’s in the showstopping, triumphant march and emphatic, therapeutic spits of “fuck” on “A Better Son/Daughter,” and in the frenzied climactic screams and guitar trills of “My Slumbering Heart.” And it remains there until the album’s very end, where Jenny Lewis lets out one last yell: “It’s so fuckin’ beautiful.” Though anguish and friction lie at the core of The Execution of All Things, it’s these moments of hard-won rapture that ring out louder than anything else.

Natalie Marlin is a freelance music and film writer based in Minneapolis who has contributed to sites such as Stereogum, Little White Lies and Bitch Media, and previously wrote as a staff writer at Allston Pudding. She also regularly appears on the Indieheads Podcast. Follow her on Twitter at @NataliesNotInIt.