People always say they admire artists who take a lot of risks. Those same observers are often unhappy when those artists stumble. But an artistic risk isn’t a genuine gamble unless there’s a real chance of falling flat on your face.

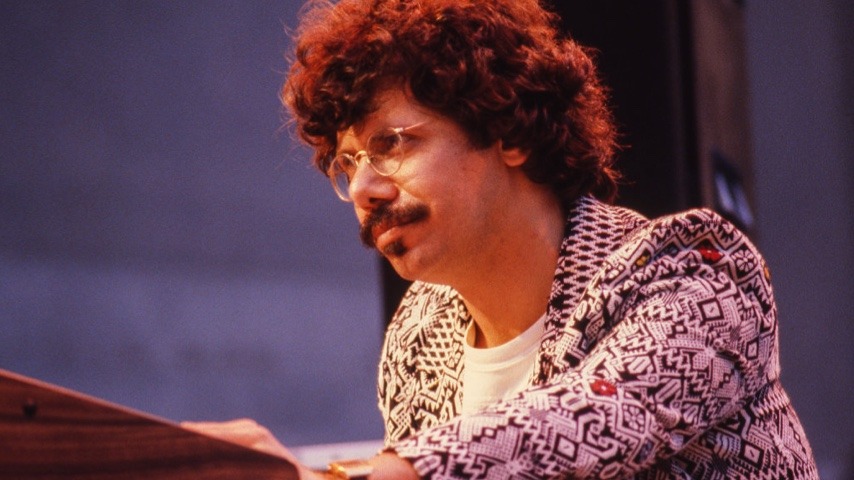

Chick Corea, who died Tuesday of cancer at age 79, was a fearless musical gambler who had his fair share of stumbles. It was those failed artistic wagers, though, that made his greatest triumphs possible. In this, he took his cue from his most crucial mentor, Miles Davis, who won a lot of musical bets but lost a few too.

In 1966, when jazz’s market share was shrinking and rock was growing not only in album sales but also in artistic ambition, Davis’s former saxophonist Cannonball Adderley had a hit with the song “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” written and played on an electric piano by Joe Zawinul. Here was a way, Davis decided, was a way to bring a new audience to jazz: integrate electric instruments and R&B rhythms.

On his 1968 album, Filles de Kilimanjaro, Davis asked his longtime pianist Herbie Hancock, Zawinul and Corea to all experiment with electric keyboards, while Ron Carter tried the electric bass. The results were encouraging enough that for his next album, In a Silent Way, Davis brought back the three pianists and added electric guitarist John McLaughlin, young British bassist Dave Holland and rock-influenced drummer Tony Williams. When Davis took the show on the road, it was with a new quintet featuring Corea, Holland, drummer Jack DeJohnette and saxophonist Wayne Shorter.

It’s easy to understand why Davis settled on Corea as his new keyboardist. The latter had already established his reputation as a skillful, inventive acoustic pianist playing Latin-tinged jazz with Stan Getz, Herbie Mann and Mongo Santamaria. Corea’s father had been a successful trumpeter and bandleader in Boston, so the son (named Armando after his father and nicknamed Chick by his aunt) understood Latin-jazz’s connection between melody, rhythm and improvisation from an early age. He started on the piano at age four.

That gave him the dance pulse and flexibility that Davis was looking for. Their partnership climaxed in the jazz-rock big-band project, Bitches Brew, an album that hit the top-40 pop charts and went platinum. It proved the economic and artistic potential of the jazz-rock fusion movement and included most of that movement’s future leaders: Corea and Lenny White (Return to Forever), Zawinul and Shorter (Weather Report), McLaughlin and Billy Cobham (Mahavishnu Orchestra), and Davis himself.

But when Corea left Davis in 1970, he didn’t dive straight into more fusion. Instead the restless, gambling artist formed an avant-garde quartet with Holland, Anthony Braxton and Barry Altschul to make some of the finest and lowest-selling music of Corea’s career. He recorded an exquisite, unaccompanied duo album with vibraphonist Gary Burton, the first of many collaborations between the two. He also made a Brazilian-jazz album with Flora Purim and Airto Moreira and called the group Return to Forever.

That album, 1973’s Light as a Feather, was a mixed bag, marred by Purim’s pitch problems (Corea never had much luck working with vocalists) and Corea’s overly decorous playing. But the keyboardist liked the name Return to Forever, and he revamped the group as a loud, plugged-in fusion band that finally settled on a line-up of Corea, White, Stanley Clarke and Al Di Meola. Clarke and Di Meola weren’t acoustic jazz players adapting to a new, amplified world; their primary instruments had long been electric bass and electric guitar; thus they had a comfortable familiarity with the buzzing tone and propulsive thrust of the music.

RTF was symptomatic of the ’70s fusion movement it helped lead. On this line-up’s first album, 1974’s Where Have I Known You Before, the themes are strong and the shifts between the hard-hitting ensemble passages and tangential solos made sense. As audiences clamored for weirder sounds and a more aggressive attack, though, the band began to emphasize technology and volume over invention with diminishing results. But Corea was unfazed; he learned as much from his failures as his triumphs and kept moving forward.

He had a choice: he could keep milking the RTF cow or he could use his new-won name recognition to pursue a variety of projects. He wisely chose the latter. That included missteps such as the two 1978 albums, The Mad Hatter and Secret Agent, featuring too many synthesizers and too many vocals by Corea’s wife Gayle Moran. On the other hand, the pianist did delightful unaccompanied acoustic-duet sessions with Herbie Hancock and Gary Burton and formed a fine, semi-acoustic quartet with saxophonist Joe Farrell, drummer Steve Gadd and bassist Eddie Gomez.

Also in the late ’70s, he joined the controversial religious cult Scientology and often thanked the church on his album covers. He never proselytized from the stage or the studio, however, and the extraterrestrial theology never seemed to interfere with his music. The one exception is the 2004 album To the Stars, an instrumental soundtrack based on Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard’s writings, which are reprinted in the CD booklet. There are some lovely moments but also many moments of overplaying.

The first time I saw Corea live was with one of his lesser electric bands at the Bayou in Washington in 1980. The stage of this rock club was filled by gifted players—most notably percussionist Don Alias and bassist Bunny Brunel—but the evening featured too many repeating unison passages, too many vocals by Moran and a leader too obsessed with unusual keyboard sounds.

Much better was the unaccompanied duo of Corea and Burton at George Washington University’s Lisner Auditorium in 1984. When the two men played Corea’s “Mirror, Mirror,” they reflected each other’s phrases just at the title suggested. They had a similar fluidity as each alternated between chordal harmonies and brisk detours through the melody. Corea’s piano phrases were fuller and more forceful than Burton’s sparser, self-contained phrases—reflecting their different personalities as much as their instruments. This fascinating give-and-take continued on tunes by Corea, Thelonious Monk and Steve Swallow.

In 1986, Corea joined co-headliners Shorter and Di Meola for a summit meeting of ’70s fusion at Maryland’s Merriweather Post Pavilion. All three sets had their moments, but the highlight was the encore, which began with a sumptuous, unaccompanied ballad duet between Corea’s electric piano and Shorter’s soprano sax before segueing into a sextet version of Corea’s most famous composition, “Spain.” Shorter’s dancing soprano lines highlighted just how rich that Iberian melody really is.

In 2006, I saw Corea, DeJohnette and Gomez play an impromptu set at the Hilton Hotel in Manhattan. The drummer and bassist had spent overlapping years with the great jazz pianist Bill Evans, who had so strongly influenced Corea as a teenager. Evans had not only pioneered new ways of improvising on modes as well as new ways of voicing and fingering chords, but he also reinvented the piano trio. A lot of pianists talk about making their bassists and drummers near-equal partners in a trio, but Evans actually did it. And now Corea, DeJohnette and Gomez were doing it too. And in 2016, I saw Corea do it again with bassist Christian McBride and drummer Brian Blade at the Newport Jazz Festival.

Just as Corea was influenced by Evans, so was banjo player Béla Fleck transformed by Corea. It was Fleck’s quest to imitate the sound of his favorite Corea records that led the Manhattan teenager to reinvent how the banjo might be played. So a circle was finally closed when Fleck finally recorded and toured with the pianist. I caught them at Maryland’s Strathmore Performing Arts Center in 2015.

Corea—with short, curly, gray hair and a blue denim jacket—sat on the bench before a Yamaha concert grand piano. Fleck—wearing graying bands and a black shirt with sleeves rolled up—sat in a chair where the piano curved. With no one else on stage and just a few feet apart, the two musicians soon locked into a marvelous rapport. They began with “Senorita,” which Corea had written for the duo, engaged in a call-and-response dialogue and then nailed brisk, simultaneous runs with clean endings.

Fleck’s “Waltz for Abby” (written for his wife Abigail Washburn and echoing Evans’ “Waltz for Debby”) involved more counterpoint in the variations, as if they were agreeing and disagreeing at different junctures. The evening ranged across tunes by Stevie Wonder, Benny Goodman and Alessandro Scarlatti, bridging the supposed gap between behemoth piano and the African/Appalachian banjo again and again.

Perhaps the most memorable Corea show I ever saw was another unaccompanied duo, this time with singer Bobby McFerrin at Wolf Trap in Virginia in 1990. When McFerrin unleashed a burst of scat-vocal syllables, Corea responded by rapping his knuckles on the piano lid. When the singer slapped his chest in time to his own hiccups, the pianist plucked the strings under the lid. They turned the piece “Echoes” into a fencing match between piano and vocal sound effects.

On and on it went for two hours that were as much improv theater as musical concert. At one point, McFerrin spotted a vase of flowers. He handed the vase to the audience’s first row, and they passed it to the rear of the amphitheater. So he handed them the flowers, a glass of water, a stool and a stepladder, and each was passed up through the audience. Finally, McFerrin threw himself into the crowd, and like a swimmer rode the waves of outstretched arms and disappeared into the night.

Now it’s Corea who has vanished into the darkness. He leaves behind close to 90 albums as a bandleader or co-leader and 23 Grammy Awards. He leaves behind a mixed track record of triumphs and misfires, but he wound up with more and greater successes than someone who might have been more cautious and tasteful in his or her choices. After all, it was Corea’s willingness to risk disappointment that made his best moments possible.