There’s not a lot Superchunk haven’t done over a career that dates back to 1989, but with their new album Wild Loneliness they were able to strike a weird one off the list: They’ve now officially made a record during a global pandemic.

Wild Loneliness, the band’s 12th album, was recorded throughout 2021, with singer, guitarist and songwriter Mac McCaughan working in his home studio over separate sessions with drummer Jon Wurster and guitarist Jim Wilbur. Bassist Laura Ballance recorded her parts at her own home studio, with a variety of guests also contributing remotely, including Mike Mills of R.E.M., Sharon Van Etten, Tracyanne Campbell of Camera Obscura, and half of Teenage Fanclub—Norman Blake and Raymond McGinley. The result is a slightly more subdued album than you might expect from Superchunk, one that’s significantly less angry than their early Trump-era last album, What a Time to Be Alive.

It might be less angry, but it’s no less concerned about the state of the world today, or the future we’re creating for ourselves—or the lack thereof. The first single, “Endless Summer,” might be the catchiest song yet about how we’re destroying our environment, and that existential fear over the condition of our planet lurks throughout the album. On “Refracting,” McCaughan acknowledges how it’s not the healthiest use of one’s energy to judge or get angry about others, even if it can be a fun distraction—something I personally relate to, as somebody who used to regularly hate-listen to right-wing talk radio to make the workday go by faster. Meanwhile, on “This Night,” the antiquated hobby of making a mixtape leads McCaughan to note that “Time will grind you down,” and on the album-closing “If You’re Not Dark,” he says he simply can’t believe anybody who says they haven’t been affected by the division and hate that’s increasingly defined our society over the last decade. Of course it’s a “catchy” record, because that’s what Superchunk do, but it’s not exactly a fun one; you can’t listen to it without feeling the weight of, well, everything bearing down on you and the band.

Paste recently spoke separately to McCaughan and Ballance about the new album. The two, who co-founded and co-own the legendary independent label Merge Records, discuss what it’s like for a band as tight-knit as Superchunk to record in different locations, and what’s changed since 2018’s What a Time to Be Alive—beyond, y’know, the obvious.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Paste: So what’s it like making a record during a pandemic?

Mac McCaughan: Well, um, it’s a little bit like making a Portastatic record in 1994, or something like that. I was working on a film score when everything shut down for the Netflix movie Moxie. And, like, I’d already started writing the music and I had studio time booked to do some different things, and then lockdown went into effect. And that time went away. As well as studio time that Superchunk had hoped to start tracking some of these songs that are on the new album. Because a few of them I started writing before the pandemic. And so the lockdown went into effect, that meant we couldn’t go in the studio, I also just kind of stopped being able to write songs for whatever reason. I was still working on the film score, but getting my mind around sitting down with a guitar, it wasn’t really happening. And that lasted for about six months.

And then once I did start writing songs, again, it became clear that going into studio all together wasn’t going to happen anytime soon. And so I just started recording at home, basically, kind of building on the demos that I had been recording, which I normally email out to the rest of the band, and then they work on their parts, and then we go into the studio and do it. But so I was sending out the demos, and people were thinking about their parts, I guess. But we didn’t have a place to go. So Jon [Wurster] and Jim [Wilber], individually would come over here to my studio, and we will both be wearing masks and sitting on opposite sides of the room. And Jon would be playing drums and I’d be running Pro Tools or whatever, and did the same thing with Jim for his guitar parts. And so we basically built the album that way. And then Laura recorded her bass parts at her house because she has a recording setup there. So you know, we never got to play the songs all together in one room, but we made the album that way. And then started sending the songs off to people that we want to collaborate with for them to add their parts. So everyone just kind of did their thing where they were.

Laura Ballance: Lonely. It was weird because you know since I don’t tour anymore, I look forward to the process of writing a record together and recording it because it’s the main time I get to hang out with some of my best friends in the world, who I’ve spent most of my life with. And I didn’t get to do that this time. It’s good to still be able to make a record this way. To have this option is great, that we were able to do it. But I found it really hard to get motivated. I was the last one to turn in my parts for the record because I just found myself … y’know, lethargic about it.

McCaughan: But we didn’t want it to sound like a pandemic record or like a home recording project kind of album. We still want it to sound like a Superchunk album. And so we got Wally Gagel to mix it; we worked on Here’s Where the Strings Come In with him in 1995 or whenever we recorded that record, he was the house engineer for Fort Apache in Boston at the time and he’s been in L.A. for a long time, but we knew he was still doing a lot of stuff, and so we sent the songs to him and he mixed them and made it sound like we didn’t record them in this little room in my basement. So that’s kind of how we got there.

Paste: Would you ever want to record a Superchunk record like this again?

McCaughan: I mean, we could if we had to, but to me, you know, part of the fun of making the record is playing the songs all together, so it’d be great if we could go in the studio. But for this album I think it worked out well. And you know, Owen Pallett doing his strings and the guest vocalists we had, everyone just added so much to it and I feel like it turned out really well.

Ballance: We certainly could, but I guess it depends on what’s going on. I have to say another good thing about it is, there was not—I didn’t even have to worry about the situation where I had to be in a room with the three of them and worry about my ears. Because they do play loud. That’s how they’re used to doing it and that’s how they like doing it, and it’s really hard to get them to be quiet. And it’s not the nature of this band. If Jon hits a drum, even if it’s as quietly as he can possibly hit it, it still hurts my ears. I’ve got to try something different. I can wear earplugs and headphones and then I just can’t hear anything. It’s too hard to … it’s hard. I was talking to somebody recently who’s a hunter, and he was talking about hearing protection that he wears when he’s going to shoot a gun. And I was saying like, ‘How does that work, because don’t you need to hear when you’re hunting? Things rustling around in the leaves, or whatever?’ And he said, ‘Well, they’re sort of high-tech, and somehow it creates the frequencies when there’s a sharp, loud sound to block that sharp, loud sound. But if it’s under a certain level it doesn’t do that.’ So I should get some of those.

Paste: It’s been about a decade since you quit touring with the band, Laura. How are your ears doing, and how do you feel about that decision now?

Ballance: I’m totally cool with [not touring]. I’m really glad not to have to do it. If I avoid loud stuff, my ears do okay. But I have to make my family repeat themselves all the time. I should probably get some hearing aids. We got a dog a few years ago and she’s loud and whenever she barks I’m like ‘dammit, Bean.’ That is just as bad as Jon hitting a snare drum. So I have that in my everyday life now and I can’t figure out how to make her quit. It’s sharp. And it just goes to prove that you can’t avoid the occasional loud sound. It just happens, and those are the kind of sounds that set off my hyperacusis and my tinnitus. I feel sort of screwed.

Paste: Oh wow, I’m sorry. It’s good you have the label as well, so you can work in music without having to play it live.

Ballance: I’m glad my whole job is not playing in a band, for sure. I’d feel pretty rough right now.

Paste: So how do you know when it’s time to make a new Superchunk record?

McCaughan: I guess it’s just when when there’s songs, you know what I mean? And when we’ve kind of done what we needed to do for the record, the last record. So for What a Time to Be Alive, we did a bunch of touring and then going into the Merge and Superchunk 30th anniversary year, we recorded the acoustic version of the Foolish album, which is its own kind of project. And we did a little bit of touring for that at the end of 2019 and went to Japan, which was kind of the end of What a Time to Be Alive touring. So that felt like, you know, the kind of cap to that whole cycle. And I was already starting to work on songs, like I said, when the pandemic came around.

Paste: So the new record. First of all, I can’t believe What a Time to Be Alive is already four years old.

McCaughan: It’s crazy to think about that.

Paste: I know. So that came out a year into Trump’s presidency and it felt really urgent, angry, pointed. Wild Loneliness comes after everything that’s happened since three years of Trump: the pandemic, the attempt to overthrow the election, Jan. 6. And to me the new record, it feels kind of resigned … like, I don’t want to say hopeless, but maybe on the path there. I mean, I don’t know, how are you feeling about the world today?

McCaughan: Oh, I don’t know, I don’t feel resigned and I don’t feel hopeless. There’s definitely days where it’s easy to feel that way. But just because, you know, the power structures that Trump played upon to basically get where he got are still there, and they’re determined not to let go of, you know, the power that they have, you know, so that part is not changed. But at the same time, I feel like, while there are days where that anger, I mean, most days, I feel angry, at some point about the political situation in this country and the success of fascism and authoritarianism to do so many people who live here, but in terms of making art and making songs and music about it, you know, I feel like it has its place, but it can’t be the only thing, you know? And so I feel like, to me, the feeling going into making this album and the way the songs were kind of shaping up was kind of informed by making that acoustic version of the Foolish album. And so I started writing the songs on acoustic guitar, and whether that led into the subject matter, or vice versa, whatever, but I feel like I was thinking more about the exhausting nature of being angry all the time, which is terrible and damaging to everyone’s psyche. But also the need to kind of look around and see the positive things that we do have, whether it’s your family, or your friends, or community, musical community, or whatever it is, and, you know, to not lose sight of those things, just in the face of just all the shit there is to be mad about. So that was kind of the point of view of this record, not, again, not resigned or hopeless, just more like, hey, you know, like, don’t lose sight of the things that we do have.

Paste: Everything is so exhausting. I live in Georgia. So on Jan. 5 of last year, we were so excited because Ossoff and Warnock both won Senate seats. And then the very next day, they try to take over the damn Capitol in D.C. We can’t even have one day to feel good about things before they try an insurrection.

McCaughan: I know. But I mean, those Georgia victories are real, you know. That’s a good thing, that’s a positive thing to hold on to.

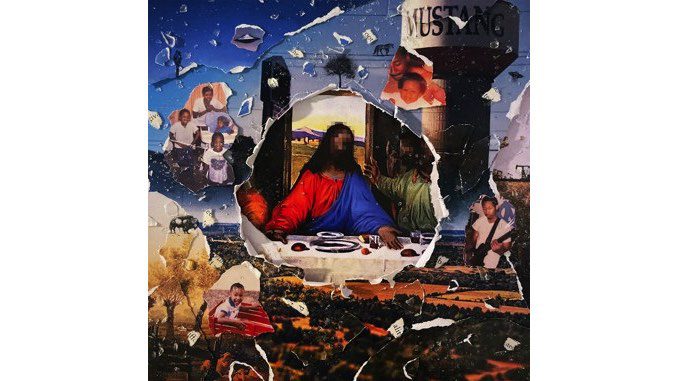

Superchunk’s 12th album,

Wild Loneliness

, is out now on Merge Records.

Senior editor Garrett Martin writes about videogames, comedy, travel, theme parks, wrestling, and anything else that gets in his way. He’s also on Twitter @grmartin.