It’s strange to think that, for a new generation of pop fans, Rihanna’s face is probably more familiar staring back at them from a Fenty ad than a record cover. Her position as a pop star these days is defined largely by her absence, which has elevated her to a near-mythological status: R9, her rumored maybe-reggae-inspired maybe-not ninth album, has become a sort of pop holy grail that can only be recovered Indiana Jones-style. Even her rare throwaway tracks, like her most recent voice memo for the Smurfs soundtrack, are frantically combed over for signs of an upcoming album, her fans transformed into oracles trying to read the signals of an all-powerful god.

Yet even if Rihanna is now better known (musically) by her absence, she was once inescapable in pop. The Barbadian superstar signed onto Def Jam when she was only 15, and for years afterward she was pop’s most reliable hit machine, pumping out chart-topping single after chart-topping single. (To date, Rihanna has 14 #1 singles, making her the female artist with the second-most Billboard #1 singles, second only to Mariah Carey.) While Rihanna’s albums were often just delivery vehicles for a handful of hit singles and then a whole lot of filler, during her imperial era she was larger than an albums artist or even a pop star: she was simply pop incarnate. She embodied pop music, permeating every atom of the late 2000s and early 2010s. Even if you’d never heard a Rihanna album in full, you knew all her hits: her voice on the radio was a nonstop presence, as irrefutably elemental as the air we breathed.

ANTI, though, was the first Rihanna album that was truly an album. Even early on, it felt markedly different from Rihanna’s previous works. In perhaps a sign of what was eventually to come, ANTI was first marked by its absence: while Rihanna had previously released albums like clockwork—one every year for seven years (save for one break in 2008)—the gap between ANTI and its preceding album, 2012’s Unapologetic, stretched out to four whole years. Hype for new music built to unbearable levels, and ANTI’s rollout—a mess of repeated delays, erratic singles releases, and even a bungled TIDAL leak—only added to the confusion and anticipation. When it finally arrived, it was defiant and unorthodox, an explosion of pop that shattered into a kaleidoscopic array of alt-R&B, dancehall, trap, doo-wop, country, and psychedelic rock. For someone who’d built a legacy on capital-P Pop, ANTI seemed like an explicit refutation of everything that’d come before.

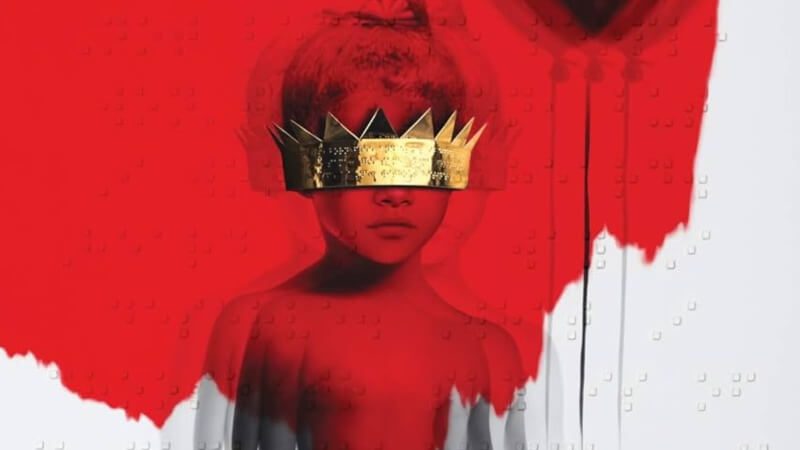

ANTI’s cover shows Rihanna as a child with a crown hanging over her head, covering her eyes; it hints already at the tension between vulnerability and celebrity that will undergird much of the album. Yet there’s another oft-overlooked detail on the cover: a poem, written in Braille, that includes the lines, “My voice is my suit and armor, my shield, and all that I am.” This focus on the voice feels right: one of Rihanna’s most memorable features is her vocals. While she was never, say, a Mariah Carey or Alicia Keys-type performer, Rihanna’s take on pop was always defined by her muscular delivery and the mechanistic precision with which she could take on a hook, giving it the body and heft to float over a strobing EDM or dance-pop production and truly hit.

[embedded content]

There was the unexpected assurance she possessed on “Umbrella,” chanting that chorus and those hypnotic ella-ella’s; the strength in her voice, that cool confidence and unflappability, made you believe in the song’s very premise—maybe everything really would be okay as long as you were standing under Rihanna’s umbrella. Likewise, on “Only Girl (In The World)”, Rihanna might’ve been asking her lover to make her feel like she was the only girl in the world, but it was clear from her euphoric embrace of the chorus that she didn’t need anybody else’s permission; she already knew she was. Her voice was defined by its badassery, forceful and assertive and capable of making every syllable burst in emphatic, percussive little starbursts of sound. (Even her eh-eh-eh’s were so remarkable and full.) Jayson Greene, writing for Pitchfork, defined this quality as “Rihanna Voice,” a phenomenon that had permeated all of pop music: you can hear its reverberations in songs by Zara Larsson, Era Istrefi, Maggie Lindemann, even Lorde.

So Rihanna’s voice has always been the space where pop, persona, mystique, and celebrity all collide, and more than on any album prior, this potent blend sits front and center on ANTI. Take “Work,” the album’s biggest hit. I’m sure even now, years later, you still remember that chorus—where Rihanna drawls the word “work” over and over again, each syllable slithering into the next in a post-verbal “wurr-wurr-wurr,” dropping the hard consonants until the chorus is all one continuous, sinuous thread. But somehow, despite their truncated state, each individual “work” still feels emphatically pronounced. The instrumental, inspired by the Jamaican “Sail Away” dancehall riddim, is sparse—bass, hi-hats, some twinkling keys, a computerized flute here and there—and all the body and thrust of the song comes solely from Rihanna’s voice, her swagger.

What’s striking to me now is how slippery and suggestive Rihanna’s voice is throughout ANTI, sliding in and out of different personas: on the country-twanged “Desperado”, she’s the lone wolf of a spaghetti Western, intoxicated by the flash of stranger danger. On “Yeah I Said It,” she’s the cool, somewhat icy lover; while the track is supposed to be passionate and horny (“Yeah, I said it, boy, get up inside it / I want you to homicide it” remain legendary lines), there’s a certain distance in Rihanna’s affect that suggests that she knows, in the back of her mind, how disposable her man is. And on “Higher”’s plaintive swirl of violins, Rihanna’s the desperate yearner leaving a 2 a.m. voicemail, voice wounded and scratchy from chainsmoking all by her lonesome all night. Each track feels like a set piece—a backdrop prepared for the almost actorly presence of Rihanna’s voice.

Just as Rihanna’s voice is impossible to pin down throughout the album, so too is the soundscape. ANTI is full of minimalistic, deconstructed pop, and it’s impressive to hear how Rihanna floats effortlessly between genres, propelled forward by her surefire voice. The Travis Scott-assisted “Woo” distorts Rihanna’s voice into a crunchy, Auto-Tuned wisp, sailing over stomping bass. And on retro doo-wop number “Love on the Brain,” Rihanna chooses a wobbly falsetto for the verses and a full tone for the chorus, inverting the usual pop music structure of full tone-verses and falsetto-choruses. As a result, there’s something deeply morbid about the chorus, how confidently she seems to assert and claim this love that beats her black and blue. (Perhaps it feels especially dark considering her own history of abuse at the hands of Chris Brown.)

The genre-bending sometimes leads to uneven, unfinished results—“Same Ol’ Mistakes” still pales in comparison to the Tame Impala original, and I’ve always wished that sleepy ballad “Close To You” had been swapped with deluxe version-closer “Sex With Me,” the track that leans the most winkingly into Rihanna Voice as Rihanna Persona—but at its best, ANTI embraces this rough-edged vision, the tracks here acting as sketches and demos for a new vision of pop. In that regard, it’s also notable to consider two of the album’s featured artists: a pre-CTRL SZA and a pre-Birds In the Trap Sing McKnight Travis Scott, both of whom would ultimately go on to have massive careers and reshape pop and rap in their own ways. With ANTI, Rihanna appeared to be passing on the baton to the next generation of stars.

Because, let’s face it, ANTI is absolutely Rihanna’s last album, unless the current wave of 2016 nostalgia becomes so powerful that it causes Rihanna to remember the concept of music. But what a farewell note to end on. Part of what I love about ANTI is that it feels so elusive, so enigmatic. After a career spent building out the template for maximalist EDM and dance-infused pop, Rihanna turned her back on that, offering up a raw, stripped-down deconstruction; a hazy, joint smoke-filled vision of where pop could go next. When I think of ANTI, I often imagine the character described in “Desperado”: an outlaw, a rebel, and a runaway from love charging into the horizon in an old Monte Carlo, wheels kicking up dust, leaving us all behind.

[embedded content]

Lydia Wei is a writer based in DC. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, Pitchfork, Washingtonian, Washington City Paper, and elsewhere. Find her online at lydia-wei.com.