Tim Heidecker is aware of his limitations as a singer and songwriter, but that doesn’t stop him from making music. Though best-known as half of famed comedy duo Tim & Eric, Heidecker kicked off his debut foray into the music world with a joke album about the late Republican politician Herman Cain, the majority of his musical work has been defined by melancholic folk rock; simple, catchy chords pulled bouncily along by his Randy Newman-esque voice, oscillating with equal amounts of ease between slyly funny one-liners that pull from his humor roots and ruminations on existential despair.

Heidecker’s sophomore solo album, In Glendale, considered the joys and pains of domestication and fatherhood amid life in Heidecker’s beloved current home in Northern Los Angeles, which was then followed by What the Brokenhearted Do—a break-up album spurred by a fake internet rumor that Heidecker’s wife was divorcing him. In between those two, he put out Too Dumb for Suicide, another political parody album, this time skewering former President Donald Trump. Not all of Heidecker’s fans like how outspokenly political he is, though, nor do they favor the other artistic avenues that Heidecker is interested in taking beyond his comedy, the latter of which has a fiercely passionate, borderline protective fanbase. He wrote about this situation on a track off his last album, Fear of Death, called “Little Lamb.” In the nursery rhyme medley, he duets with Weyes Blood’s Natalie Mering, singing to the embittered fans that he’s lost for not kowtowing to the demands of those who’d prefer that he just stick to comedy.

Ultimately, Fear of Death was always going to be a tough act to follow: a raucous, gorgeously produced collaboration between Heidecker, Mering, The Lemon Twigs, and a laundry list of additional musicians and engineers. The simplicity inherent to Heidecker’s shaky command of the form was given a much-needed guiding hand. It shaped an album unlike any Heidecker had put out previously: eagerly experimental and, as a well-documented and passionate fan of the band, his most overtly Beatles-inspired (it even features a bubbly, chord-shifted take on “Let It Be”). Fear of Death was a textured, deeply personal confessional about mortality and fear of the future that doubled—with its symphonic melodies, wild guitar inflections and blunt, funny lyricism—as a celebration of life. It countered Heidecker’s limited musical abilities and penchant for poppiness with grim subject material that was then given an ironic beauty. When it was released in 2020, it felt like a balm of comfort during dark days, an acknowledgement of the feeling of utter hopelessness, yet, implicit in the joyful musicality itself, a simultaneous refutation of it.

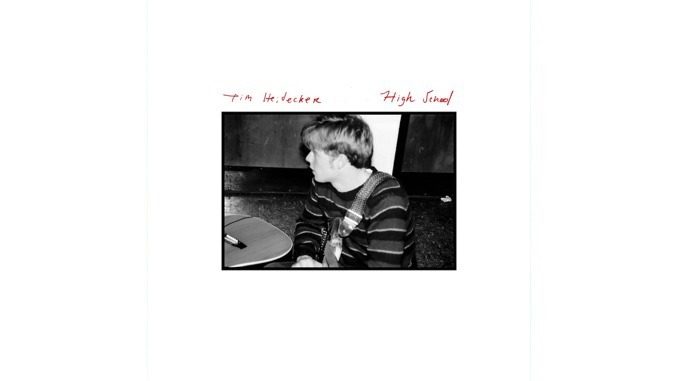

Two years later, Heidecker has returned with High School. It’s an album about the past that, on the surface, is somewhat ironically juxtaposed with Fear of Death. But while High School seems contradictory in its inverse preoccupation with Heidecker’s history, it is still very much about his complicated relationship with his future. High School is a country-inflected, folk-pop portrait of Heidecker as a teen in the early ’90s, growing up in the Philadelphia suburbs. It hones in on his first love: his lifelong passion for music.

Heidecker was always a tenuous musician, but before comedy he wanted to pick up a guitar and play like Neil Young. The influence of music on his personhood endured until he reached a point where he felt like it made sense to really make some; where it felt like the years had finally gifted him with something worthwhile to say. So now, he says it. He retreads the well-worn territory of coping with getting older, wondering if he’s peaked, acknowledging that the past is fading away from him like a memory that’s fading in and of itself. This time, instead of worrying about that black void waiting down the road for him someday, he remembers a troubled friend who died too young, and a girl he liked that his cousin stole from him, a schoolyard fight between two mismatched kids, and the inspiration he drew from seeing one of his favorite musicians perform live on television.

The album’s sequencing makes its songs fit like pieces in Heidecker’s collective puzzle, the warm moments he holds fast to and the lingering regrets that helped to shape him into the person he became. Still, he fixates on the things he should’ve done, the alternate choices he could’ve made that, perhaps, would have turned him into a completely different person. On “Buddy,” the tender, toe-tapping opening anthem that sees Heidecker reflecting on his depressed, stoner friend who, in Heidecker’s words, was gone before he was gone, he wonders if there was something he could’ve done to save his ill-fated pal. That song is succeeded by “Chillin’ in Alaska,” in which Heidecker looks back on a camping excursion where insecurity and second-guessing kept him from asking a girl out. Heidecker wishes he had been bolder in that moment, not unlike the memory of a fight between two kids that Heidecker tried and failed to stop through adult intervention, which he chronicles on “Punch in the Gut.”

In between songs about the past, Heidecker conveys his current insecurities; how he’s not thinking about himself enough, how he has trouble waking up some days, how he is forever uncertain about the road ahead. On “Get Back Down to Me,” he admits to losing touch with himself, while “I’ve Been Losing” shows him grappling with the nostalgia for his perceived best days. “Oh, I’ve been workin’ / Workin’ myself up to the fact that my best days are behind me,” he sings, though by the end of the track, he implicitly understands it as mostly absurd anxiety (“Oh, I’ve been talkin’ / Talkin’ too much / Maybe I should stop and listen”). He worries about the happy memories he’s already forgotten on the ethereal “The Future is Uncertain,” in which Heidecker’s voice echoes and wanes like his disappearing youth. Overall, the uniting, thematic thread in High School is Heidecker’s obtrusive anxiety, specifically in relation to the periods of his life that he no longer does, or does not yet, exist in. But it’s his present that makes him the most anxious because of its very impermanence as he lives through it.

As Heidecker turns towards the past, so, too, does his music take a step back. Lacking quite the exhaustive collaborative work seen on Fear of Death, and stripping Heidecker back to a more threadbare musical approach by comparison, he is nonetheless joined by Fear of Death producer Drew Erickson, along with friend and fellow musician Mac DeMarco and Fruit Bats leader Eric D. Johnson. The end result is an album that is undoubtedly lacking in contrast to his last. It might be a little unfair, since the two are musically very disparate. But it’s hard to not draw comparisons to Fear of Death, both in the albums’ subject matter and the clear backtrack in overall quality from one to the other. Perhaps it’s the more restrained production work or the absence of Mering’s gossamer backing vocals, but the cracks in Heidecker’s vocal abilities are more apparent this time around. He strains awkwardly on tracks like “Punch in the Gut” and “Stupid Kid,” where certain lyrics are set to melodies that fall discomfittingly out of his range.

Still, High School is leaps and bounds more mature than his pre-Fear of Death work. It makes clear that Heidecker is committed to this newfound maturity in craft and to partnering with people who can help it flourish, as he continues to explore a creative area that falls just a bit outside of his comfort zone. But there was an intricacy to Fear of Death that benefitted the simplistic lines and Heidecker’s unimposing, if pleasant voice, begetting profundity between the marriage of music and lyrics. On High School, the most prominent difference is that step down in instrumental complexity, leaving his shakier musical qualities more vulnerable. “Buddy,” “Chillin’ in Alaska” and his disco-tinged, Kurt Vile collab “Sirens of Titan”—reminiscing on salad days listening to the Velvet Underground on his waterbed as politics loom in the background—end up the album’s clear standout tunes, while the meat in the middle flows from one to the next until it all seems to become one in retrospect.

Though Heidecker himself would probably be the first to tell you he’s by no means one of the best working musicians, there is a pervasive warmth intrinsic to the music he makes, between his voice, the sweetness of his unpretentious melodies, and how he sings plainly and humorously about universal anxieties with a soft touch. The very act of being honest about such worries ends up conducive to a sort of communal, musical therapy. But in being less adventurous overall, High School is less perceptive and less honest, and the unvaried nature of Heidecker’s preoccupations means they end up less incisive as a result. Heidecker stumbles the most in the way that he repeats himself; he’s singing about floating down Kern River on a summer’s day, and wondering what he did with his time, but he’s still just singing about his fear of death.

Brianna Zigler is an entertainment writer based in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared at Gawker, Polygon, The Playlist, Consequence, Little White Lies and more, and she writes a bi-monthly newsletter called That’s Weird. You can follow her on Twitter.