Lip Critic began as a joke. When Bret Kaser and Connor Kleitz first approached Danny Eberle about starting a band, it was to form a punk project called the Milkman of America. The idea, supposedly, was to write songs about how milkman jobs have become obsolete. Even when the Milkman of America became Lip Critic, the band was still hanging on to the bit. Their image is a MadLib: SUNY Purchase schoolmates inspired by Gabber Modus Operandi, Héctor Oaks, MC Ride, and Autechre, writing songs about faith healers, bogeymans, eastern seaboard gas stations, and loan sharks in bizarre, boundless languages. Curiosity killed the cat but it powers Lip Critic’s fucked-up, nimble, trickster engine. Every person I’ve recommended this band to has called a wellness check on me.

There’s no telling where the line between fact and fiction stops blurring for Lip Critic. They make illogical music—head-pounding performance art puked out of two synthesizers and two drum kits—and don’t seem overly eager to fit into any one box while doing so. Kaser and Kleitz fiddle with their samplers like Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd played guitar. Danny Eberle and Michael Sandvig turn their kits toward each other like Brian Chippendale and Greg Saunier did before improvising for an hour. And Lip Critic are as serious as a heart attack about this shit: ecstatic hardcore style lathered in delicious, chest-bursting dub music and volatile, seductive storytelling. Tracks like “The Heart,” “Toxic Dodger,” and “My Wife and The Goblin” kiss you on the cheek then disembowel you. Hex Dealer is anxiety personified.

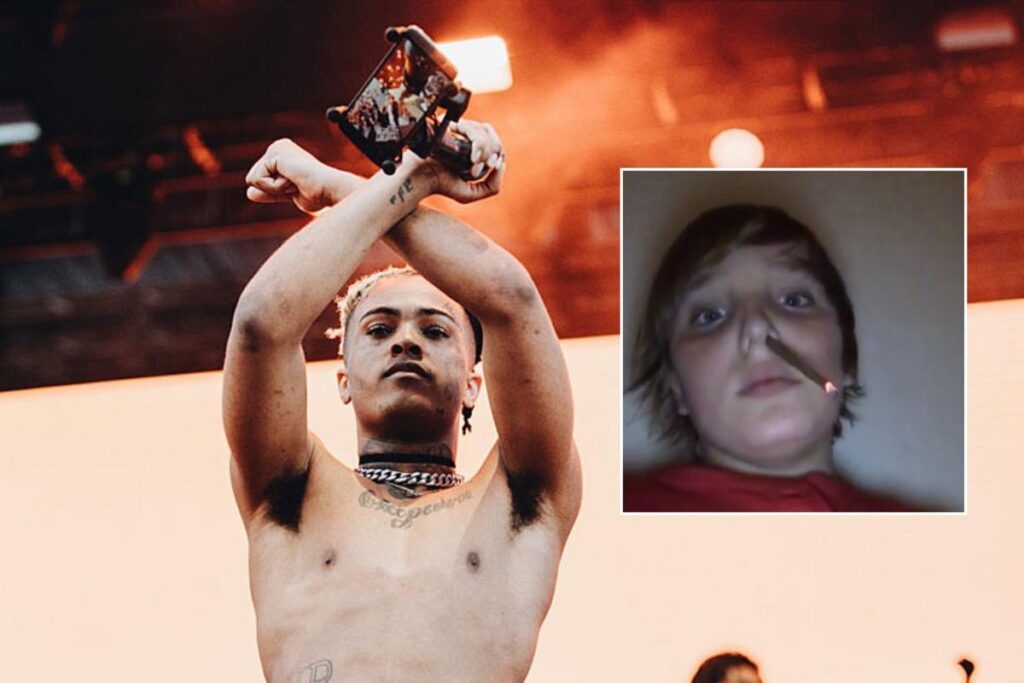

When the press materials for Lip Critic’s new record, Theft World, landed on my desk, my first reaction was: What the absolute fuck am I looking at? These songs exist because, while the band toured Hex Dealer two years ago, Kaser made a life-changing discovery: his identity was stolen, and the culprit not only bought all of Lip Critic’s Bandcamp catalogue, but a bunch of other artists’ catalogues, too. He turned out to be a real whacko: a guy draped in a Five Nights at Freddy’s hoodie who thought Lip Critic’s music featured hidden codes to a scavenger hunt—which he solved, of course. The scammer had thought up characters and liminal spaces that were, as the Partisan Records one-sheet puts it, “initially seemed incoherent but gradually became captivating.” But, being agitators at heart, Lip Critic didn’t bother telephoning the cops. Instead, they took the scammer to a 24-hour halal joint and taped him reciting this impossible mythology. I ask the band if any of this is true. “Well, it happened,” Kaser responds. “It’s an insane situation, but you got to make the best of it. You got to make lemons with lemonade.”

When Kaser’s personals got lifted, he and Lip Critic were already working on the Hex Dealer follow-up—four days of recording, 15 to 20 different song ideas. But they scrapped everything to make Theft World. “It was one of those moments where it all compounded into something that we thought was worth the torture, but it was a little bit torturous, you know?” Kaser says. When I interviewed the band two years ago for our Best of What’s Next series, Kaser told me that plans for another LP were already in the can. But whatever record they were making “got disappeared,” to use the frontman’s own words. It’s lost, the band concurs around him. “Maybe we’ll do something with it eventually, but we have this pretty strong conviction that we’re not going to put out a record for the sake of putting one out,” Kaser continues. “It needs to feel like it has a reason to be there and there’s a progression that’s pertinent to where we’re at as artists. Once we had started to formulate the ideas for Theft World, the previous record felt moot.”

Kleitz chimes in, mentioning that even though one or two songs on Theft World began in those earlier recording sessions, it was a “complete aesthetic and technical overhaul.” But Kaser confirms that the pivot let the band restart, elaborating on how he and Kleitz “had some conversations on drives during the tour where we were formulating the new ideas, and there was a lot of stuff that felt like we were grasping at something that wasn’t there until we hit the Theft World pocket of ideas.” Suddenly there were four, even five Lip Critic albums waiting to be made. “We were whittling it down, trying to make it a tight, no-fat record. We definitely could have made this the fattest record of all time.”

The initial Hex Dealer follow-up, which was called Fur Coat early on and then Lip Prosperity Casino and Resorts by the end, had a lot of legal hurdles to overcome, largely because of the sampling. “We had cut tracks out of only Twitch streamer audio, and we thought it was amazing,” Kaser reveals. “Then we ran into clearance issues, trying to get streamers to sign off on having their voice in the tracks.” But sample legality aside, Lip Critic started questioning the validity of that record. They asked themselves, “Why does this exist?” and “What are we actually saying with it?” Kaser admits that the ideas were fueled by curiosity and experimentation more so than purpose. It wasn’t as thematically dense as the unnerving, demonic Hex Dealer, nor was it as confrontational or destructive as Theft World.

Theft World features more batches of jam audio, soft synths, and cut-out, pitched-up one-shots than it does sampling of foreign material. The riff in “Legs In A Snare,” for example, isn’t coming from guitars but a re-amped 808 harmonized into power chords. Most of the programmed drum parts were pulled from samples that the band has collected over the years, while field recordings were employed sparsely. Kleitz chimes in to call Theft World an “organic sound design,” which he realizes is antithetical to the record’s title. But the proof is in the hardware—and in the drums especially, which get presented not as anchors but catalysts. Early demos feature electronic drums that transform once Eberle lays a slam death metal or blast beat on top of them. Kaser responds by repurposing his vocals to match the intensity, because the kit dictates where every song goes in a visceral, commanding way. “That’s where the footprint comes in, when the drums guide the song stylistically,” Eberle says. “Everything is Lip Critic, but the drums lead us there, which is very cool and exciting, because it never feels like we’re doing exactly what we’re supposed to be doing with the song.”

That unpredictability and chaos is threaded into everything the foursome makes, but Kaser and Kleitz perfected their own formula while making Theft World. They would build out production loops together, bring them into the studio, put drums over them, and then plug the mixes back into their computers—Frankensteining tracks into these fleshed-out, pocket-sized bedlams. “We got that method down to the point where it was just a matter of adding little elements to the end of tracks,” Kleitz recounts. “Last-minute sound design stuff that was brought to the table, in terms of putting the bow on this record, a lot of noise, a lot of resampling, a lot of additional drumming.” He even does vocals for the first time. After Hex Dealer was finished, Lip Critic started changing the outro for “Milky Max” by having Eberle stand up from his kit and scream his ass off in the mosh pit. It was the band’s attempt to give their music a life onstage that’s separate from that on the album. Sandvig reveals that a lot of Theft World got figured out on stage, as the songs turned into “bigger beasts” on tour. “Talon” was a big beneficiary of this.

Broadly, Theft World is about theft’s intersection with social, political, and artistic identity. Less generally, Kaser says it’s an album “all about romance,” as stories of hope and sweetness show up as counterpoints to the glib grimness his band so famously doles out. The “trust him with my life and more” repetition in “My Blush (Strength of the Critic)” is imposing while the stillest parts of “Shoplifting” give us the prettiest image of Lip Critic yet. The new jeans and gas station hoagies from Hex Dealer are replaced with junk space, suitcase autopsies, Honda vans, deep fryers, burgundy hands, shooting stars, and flooded lungs. Pastoral language metastasizes in the paint-splatter, class-disparate carnage of “Debt Forest.” Kaser’s flow is surgical when he’s weaving together lines like “cough into white handkerchief, all the mycelium scorched from earth / the spore still asleep under the dirt, the cow is just the unmade purse / best believe I know its worth.” He’s a zip-tie and a turtle dove. The Theft World revolving between his soft teeth is watertight, torn-through mayhem.

The themes of addiction and predatory marketing in “Jackpot”—a song whose early demos sounded, as Kaser tastefully puts it, like “a Yeat album getting blasted in a kiln”—are especially compelling, as the song unfurls from the perspective of a character obsessed with gambling to the point that his life is destroyed. There’s a “come to Jesus” moment in “Jackpot,” when the protagonist mourns the path he could have taken, and the band puts a sublime, synthetic organ beneath it. It’s a mad, clanging track split open by a suction of synthy respite. “We wanted this record to have a huge amount of dynamic range,” Eberle adds. “We’re obviously still going to make songs that just blast for a 1:20 and then they’re over, but we really referenced albums that give you what you want even when you don’t know that you want it.”

Theft World is a less clubby record than what the band expected it to be. Kaser and Kleitz are huge dub guys—students of The Bug and Rhythm & Sound, specifically. At this point, the dancier ideas are baked into Kaser’s subconscious motivations. Everything he makes is bathed in those influences, but he wanted Theft World to have extremes on either side, and Sandvig’s metal obsessions aided in that. “I wanted there to be very quiet moments, and I also wanted there to be really noticeable slammy and doomy moments,” Kaser elaborates. “Then there would be these R&B chord movements and things that feel kind of ambient. I’m just a huge Stevie Wonder nerd. He’s the G.O.A.T. He’s like Superman. I was listening to a huge amount of him during this, because I kind of always am, but there would be moments where he weaves these harmonies in and out of songs where you never expect them.” If you liked Hex Dealer and plan on tuning in to Theft World, you might ask, “Why are there so many chords all of a sudden?” The answer is: Kaser was listening to “a lot of very chord-y music.”

Four years after completing Hex Dealer (and two years after releasing it), Eberle sees Lip Critic’s breakout record as one with tons of variety that’s nearly all one-note—in the sense that it’s “just a blast.” “It’s like, boom, boom, boom, 30 minutes. Now you look like Drake and Josh after they rode the Demonator roller coaster,” he specifies, offering a good, mid-2000s Nickelodeon shout. “‘Legs In A Snare’ is toe-tapping music for two minutes, and then there’s this weird breakdown that’s still groovy. I’m doing a break that’s recorded to a tape machine, and it’s this really crunchy-sounding drum part, and Brett’s rapping rather than singing, but he’s screaming it, too.” It’s aggressive music you can still bump to, getting Lip Critic one step closer to their very own posse record.

Theft World juxtaposes the loud, moshy assaults with some shockingly melodic, pretty decorations. It’s Lip Critic at their most potent. “Legs In A Snare” is, as Kaser squares it, the best “bird’s-eye view” of Theft World’s themes. From my vantage point, it’s an album swallowed by a thousand broken systems killing everything and everybody, yet it’s still filled with characters trying to exist inside those systems and trying to figure out how to fight back against them, all while having a crush. But Lip Critic doesn’t cop to that “falling in love at the end of the world” swill. Theft World is about “eating an absurd world and falling in love with it as you digest.” “Legs In A Snare” is about being a freak and getting what’s yours. “It’s like, oh, fuck. Everything is on fire and I’m still falling in love,” Kaser affirms. “It’s directly about that idea of how things are stolen from you but you can steal back. You can steal to empower.”

[embedded content]

Theft World is out May 1 via Partisan Records.

Matt Mitchell is the editor of Paste. They live in Los Angeles.