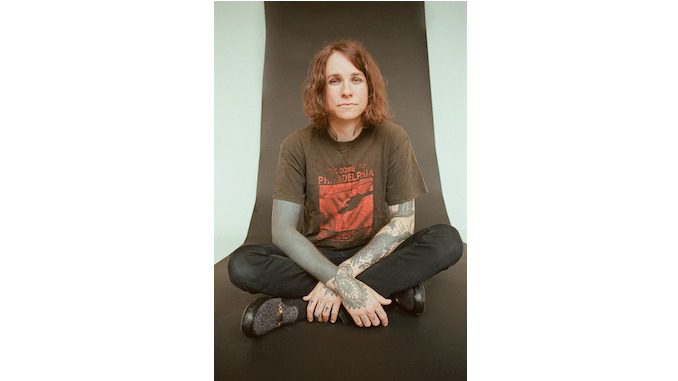

Laura Jane Grace crafts descriptions of pain and frustration that feel tangible and relatable. Much of that is due to her impeccable writing talent that has made her band Against Me! one of the most revered punk acts of the past 20 years, as well as her solo work under the name Laura Jane Grace & The Devouring Mothers, but it was also a result of coming to terms with her identity and the inner turmoil that manifested in many painful ways.

Having publicly announced that she was transgender in 2012, Grace is about to celebrate her 41st birthday in November, a decade of being out next May and four years sober. In her face and in her stage presence, she beams with pride and vigor that has only intensified with age. Despite being criticized as a sellout throughout her career, whether for previously signing a deal with a major record label, working with Rock the Vote for the 2008 election, joining forces with Joan Jett and Miley Cyrus to raise money for charity or writing a bestselling memoir, Grace has prioritized her own happiness and growth without sacrificing what made Against Me! so revolutionary in a time where punk rock and danger were fading back into obscurity. She rode on the margins of the underground and the mainstream, introducing several generations of people to the power of punk rock, radical politics and an unwavering commitment to staying true to oneself, even if that realization may come later in life.

In the face of addiction and trauma while harboring an integral part of one’s identity, Grace has found healing and solace in vulnerability as she realized a need for her story to be told truthfully. She spares no detail, whether on the scathing dissections of the suburban Floridian landscapes on her older records or the unraveling of what comes with transition and divorce on Transgender Dysphoria Blues. In her newest project with Audible titled Black Me Out, several hours of interviews are condensed into another facet of Grace’s story as she tells the tale of the events leading up to the brief breakup of Against Me!, and the subsequent healing she found that came with transitioning—a word that takes on many connotations in the context of her life.

Below, listen to an exclusive excerpt of Black Me Out and read our conversation with Laura Jane Grace.

Paste: You mention a lovely anecdote in the beginning of Black Me Out about writing a fake band name to wear on a jacket. I love this shared experience of us punks doing stuff like that to be cool at a young age.

Laura Jane Grace: Well, looking back at it, it was fun to pretend. It was fun to imagine the possibilities. It was expressing and creating yourself, imagining band names and then drawing the logos and putting it on your notebook or jean jacket. I was unloading some furniture from storage recently and found my childhood desk. On the bottom of one of the draws, I wrote it.

It wasn’t a money thing. It wasn’t being young and saying I wanted to be a rich rockstar. I think it was being attracted to that gang mentality of being in a group and having this family when you were a kid who felt alone. I felt alone oftentimes as a child and I liked the idea of having a crew. You against the world. I was attracted to all those elements of it, even before I ever picked up an instrument and committed to having to learn how to play it. That came after the fact, which is honestly pretty punk. When it comes down to it, all you need is three chords and a backbeat and there you go! I kind of let those things guide me through life. I followed my music tastes and my music taste brought me friends.They brought me opportunities and took me on great adventures and we traveled the world. I never would have had it otherwise, and I’m super thankful for it.

Paste: Did you have a suspicion that you may be different when you were a child?

Grace: The age gap that was there between my brother and I meant that we didn’t really play together in those ways when I was eight or so. In that phase when you’re really playing with toys, he was too young to understand the games we were playing or the complicated plot lines me and my friends would come up with. It demonstrated to me that the differences between us weren’t wrong, but there were differences nonetheless. In the eyes of family members, I was considered a more feminine child and I was considered more sensitive. My brother was much more rough and tumble. When you have two children, you’re going to get compared.

Paste: It’s really interesting how seeing Kids in the Hall made you see these performances of femininity at a young age which has stuck with you throughout your life.

Grace: Demonstrations of gender play, when it was done in a positive light, meant so much to me when I was younger. I was confused, and Kids in the Hall I’d watch when I was 13-14 years old on Comedy Central. The skits are brilliant and it was a level of humor that really spoke to me. They had those examples of gender play where all the cast members would dress up in drag and play characters, and you’d look at some of them and think they’re really pretty or, for lack of a better term, they could pass. Fuck passing, don’t get me wrong, but when you’re a young and confused trans kid, that’s a fear. You think “Could I ever pass?” It meant something because you saw it and realized if it can happen for them, it can happen for me.

Paste: How did that realization influence your creativity and life path?

Grace: There are so many things about myself that I didn’t understand at a young age because I didn’t have the words for it. I didn’t know I was transgender because I had never heard the word transgender. I just grew up with a suspicion that there was something really wrong with me and I had certain feelings that I needed to suppress and keep secret. If people found out about that, I would be in trouble. As you get older and you learn the terminology, you have this internalized shame but, at the same time, you’re forming your identity and that creates conflict. Oftentimes, that translated into self-abuse and trying to detach because reality was a little too fucking real. Growing up with that awareness that there’s something that sets you apart makes you hyperaware, because you operate in this situation where you feel under suspicion even when you’re not. You can’t let signs of whatever it is out, so you’re never fully in the moment. It just makes you observant. In a lot of ways, that’s what led me toward writing. You’re in your head, thinking about the description of a situation, how it looks and how you look to other people. However, it creates that situation of being “other” because you’re on the outside and aren’t part of the group even if you’re being accepted into the group. There’s something about you that they don’t know, and if it came out, it would change the relationship. If you know that even on a subconscious level, how can you ever really connect in the moment?

Paste: There is this hyperawareness as LGBT+ people where we want to hide out of fear and protection, but you also wonder if you are valid enough and if others can “tell.” It’s like a performance.

Grace: Completely. It was something that I had to learn as far as coming out then when I didn’t grow up with a queer community. I didn’t know other transgender people. Then, you come out and there’s a part of you that thinks you’re naively going to be welcomed with open arms. I came out really later in life and I’ve had this whole other set of experiences, and I’m over here realizing that it’s gonna take work to feel like you fit in even after you come out. Maybe some of that’s imposter syndrome or internalized transphobia or whatever. It’s just not easy.

Paste: When you talk about how not everyone is going to welcome you, there’s a lot of parallels to what you discuss in Black Me Out with growing up having a utopian perception of punk and realizing the hypocrisy, especially when you were in talks with major record labels.

Grace: I think that these are systems that reoccur in microcosms. I hated high school. I hated the power dynamics. I hated popularity contests and teams and clubs. I didn’t want to belong to those things.

Paste: So basically school as a whole.

Grace: Basically! I did not like the structure of school, and I got beat up a lot. I could not wait to get out. At the time, punk rock seemed to offer this alternative to that. Me and my small friend groups had to invent our own version of punk and that eventually led us to other punks because there weren’t any in our city, but half an hour north there was a city with a scene. Two hours north, there was another city with a bigger scene and actual shows were there. You get out and you meet people and want to become part of a bigger scene until you realize, “Oh shit. It’s just a recreation of high school.”

You had the popular punk kids and the not popular punk kids, and oftentimes that popularity is based on the same things that gain popularity in high school like the good looking kids or the very male-led scenes. I didn’t take kindly to that either, I thought it was bullshit. There’s some times I found myself trying to participate and play the game, and other times where I would drastically rebel against it. The things I liked about punk rock were the messages that, especially the English peace punk bands had, where you think for yourself and question everything and create safe spaces. Once I thought for myself, I realized that I was the one practicing every day and talking to labels and going into the studio. To have people outside of that who had no idea what the inside of the experience was like and assumed that signing onto Fat Records meant I was being carted around in private jets when you’re like “No!” It was offensive to me that people thought they had authority on my life.

That, plus the self awareness of this thing inside me that’s a secret, made me double down and say “fuck you.” I’m going to make these decisions that are good for me right now. It was stressful, it added a lot of tension, and it took the enjoyment away from it which sucked. It’s no good when people are angry with you for doing something that doesn’t really affect their life and they’re upset that you signed to a certain label when it doesn’t harm them. We’re not running guns here! It’s just music, and unfortunately there are inherent aspects of capitalism that are going to be involved because we live in a capitalist society. I didn’t create that, and I wish it wasn’t the case. However, ignoring it doesn’t make it go away.

Paste: We all have to play this game as much as we don’t want to, because it’s a matter of survival. We do the best that we can with what we are given.

Grace: It’s also other fallacies involved where these small indie labels that we started out on were the ones who ripped us off. Those were the ones who didn’t account properly, whereas signing a major deal, those motherfuckers just gave us a bunch of money and we didn’t have to pay it back. They gave us regular accounting that showed where every fucking nickel and dime went. I get that they’re a huge company, and there’s dangers that you’re going to be lost in that, but other people are totally fucking ripping us off. I see how big the houses are of the owner of a small indie label in Gainesville, Florida that we started out on. I live in a room paying $200 a month in rent and you got a seven bedroom house? You see the inside of something and how it works, and then you see other people on the outside not realizing that and telling you how to conduct your life in the way they see fit. It was alienating.

Paste: From the sound of this and your descriptions of some of the trouble you got into on Black Me Out, you reached your breaking point.

Grace: Unfortunately I have something about my personality that’s ingrained where if I tell someone directly how I’m feeling and what I need or want, it’s dismissed. It’s only ever listened to when I flip the fucking table and say, “Hey, this is what I’m saying.” Then, people have a tendency to say I’m an asshole when they wouldn’t fucking listen to me. It’s not a personal thing, but oftentimes I feel like I have trouble communicating and some of that is being a sensitive person. Maybe sometimes a little too trusting of a person too. You have to set your boundaries in overtly defensive ways otherwise you get crushed or taken advantage of.

Paste: As a longtime fan of your work, I can see your growth and how you’ve found that balance between what you’ve always wanted out of music, what you wanted for yourself and what you need to survive without sacrificing the principles that Against Me! was founded on. I also noticed an underlying current of fear when you discussed considering making these changes that were considered “selling out.”

Grace: Back in the day, I was under the impression that if I didn’t keep growing or getting more extreme, it was going to collapse. Maybe that was the nature of how the relationships with the band came together, other than me and James who went to high school together, but the other players were just strangers who you end up in a band width. You have these ambitions but then you don’t know if we’re on the same page because the drummer wants to be a history professor but you’ve never gone to school. I would look at other bands that didn’t go beyond whatever label it was, and I saw their decay. Maybe they had a record and people were really into it, but if you didn’t change and challenge people, they lost interest by the next record. If you weren’t supporting yourself with it and getting to a place where it could be your livelihood, interests were going to wane and people were going to move on with the band and it would all fall apart.

My strategy was to blow it up and keep getting bigger until the wheels come off. I can look at these other bands and I know what’s going to happen if you stay on Fat Records for the rest of your life, and maybe that would’ve been a good thing. That wasn’t the way I was thinking. Some of that was also a self-destructive thing too of not expecting to live past your 20s and heading for that 27 age. Some of it was also the denial and self-hatred, but it all pushed me there. Part of being an artist and a songwriter is when you work with producers and they’re telling you to dig deeper. If you’re doing that, and you have a huge secret inside of you like being transgender, you can’t get around it.

Paste: How have you learned to deal with these self-destructive tendencies and care for yourself after transitioning?

Grace: It’s multifaceted and comes from a lot of directions. There are the tropes set by older people where it looks cool to smoke cigarettes or that whole “rock and roll chic” thing. I never got into heroin or anything like that, but I definitely got into harder drugs and there was a part that was fueled by thinking this is what you’re supposed to do. If you’re a punk rocker, you’re supposed to get fucked up. It’s a common bond where you find yourself thrown into a situation with strangers in a music scene where you’re not sure what you have in common other than that you like to get fucked up. That’s the thing that bound you.

But then you have the unhealthy side of suppressing a part of you or hating it, and it manifests as self-destructive. It’s the lonely hours when you’re by yourself and can’t stop drinking, or you can’t stop fucking doing whatever you’re doing. You’re only doing it because it detaches you from reality and you do not have to deal with whatever your problem is if you don’t confront it. That’s where it became unhealthy.

Touring is vicious too, and it does things physically to you. I still have residual pains from 20 years of touring. Sometimes the only thing keeping you going is the drink at the end of the night or right before you go onstage. There came a point a couple years ago where I made a decision to where I realized I needed to dry out. I’ve been dry for three years now. I didn’t go to a program. Part of it was this process of self-acceptance coming out of transitioning and thinking that I needed to do this the healthy way. Part of it was becoming a parent and thinking about the example you’re setting there. Part of that is the physicality where it hurts to be hungover. You also want to honor your craft and I would like to do things for as long as possible.

I found certain things physically that made me feel better than getting fucked up. I love running and I go running every day to the point where it’s detrimental. Also getting into yoga and realizing I like the way my body feels. Maybe it’s part of getting older, but it’s good to be there.

Paste: Congratulations on three years! I appreciate your vulnerability, especially with sharing yourself with your autobiography and now Black Me Out. What inspired you to become so open about your life and experiences?

Grace: When first approaching this, I wanted it to be called The Last Interview. We veered away from it, because it was cut from interviews but the interview wasn’t present in it. It felt unique, and it felt like the end of a period of examination in a way of me being done talking about this. I don’t want to talk about it anymore, but it feels good to have talked about it. It felt unique to do it at this time because we’re existing in this weird limbo zone where there’s a before plague time, and we’re not out of the plague [laughs]. You feel like you’re almost on a ship that’s going down and you’re scrambling to hold onto bits of it and in a way, it’s a weird psychological purging where afterwards you’re like “Okay, here we go. Let’s go to the future now.”

You can listen to Black Me Out via Audible here.

Jade Gomez is Paste’s assistant music editor, dog mom, Southern rap aficionado and compound sentence enthusiast. She has no impulse control and will buy vinyl that she’s too afraid to play or stickers she will never stick.