The highway of pop-music history took a detour on the backroads during the folk music boom of the 1960s. For a brief period, musicians could be celebrated not for making a big noise, but for crafting a small sound; not for finding something new, but for rediscovering something old; not for describing universal experiences, but for sharing exceedingly personal encounters.

Of course, there was acoustic folk music before that decade—and has been ever since. What was different, for a while there, was a large enough audience that a singer with an acoustic guitar and a personal story had the financial incentive, the financial security, to not only get better, but to also become distinctive. For a moment, it was hip to play old styles from the Appalachian Mountains and Mississippi Delta in stripped-down arrangements.

Out of that scene emerged some of America’s finest songwriters: Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Richard Thompson, Leonard Cohen and Paul Simon. And some of our finest interpretive singers: Joan Baez, Judy Collins, Mary Travers, Maria Muldaur, Sandy Denny, Emmylou Harris and Bonnie Raitt. Many of them are better known for their post-folk recordings, but they all got their start in the coffeehouses of the ’60s.

But behind these well-known names are a host of others who did important work that shouldn’t be forgotten. Some of them were men such as Tim Hardin, Phil Ochs, Fred Neil, Richie Havens, Christy Moore, Bert Jansch, Tymon Dogg, Eric Anderson and Tim Buckley. But often they were women, who have always had to work harder and put up with more garbage to get the same recognition as their male peers. Women such as Buffy Sainte-Marie, Odetta, Bonnie Dobson, Sylvie Fricker, Barbara Dane, Linda Thompson, Mimi Farina, Judee Sill and Linda Williams all did worthy work that’s not as well remembered as it should be.

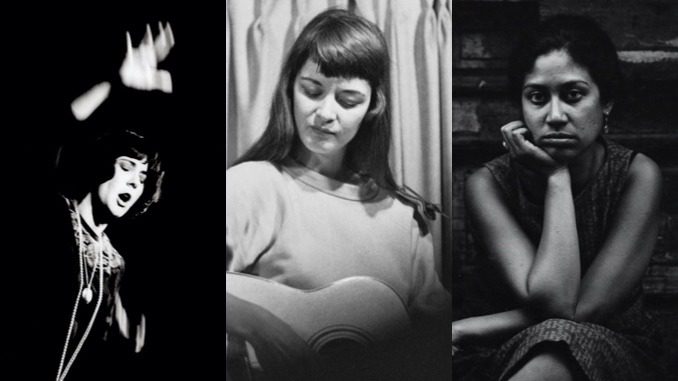

Another such woman, Judy Henske, died last month at age 85 on April 27. Over six feet tall with dark bangs, she filled old folk and blues tunes with her immense, booming alto. She cared less about “authenticity” than pulling out the musical potential of these neglected folk songs. Her 1963 version of “High Flying Bird” proved so memorable that the Billy Edd Wheeler song was subsequently recorded by the Jefferson Airplane, We Five, Neil Young and Richie Havens—who also sang it at the original Woodstock Festival.

Henske was a regular on the ABC-TV folk music show Hootenanny, and she co-wrote “Yellow Beach Umbrella,” later recorded by Three Dog Night and Bette Midler. Her first husband was Jerry Yester of The Lovin’ Spoonful and The Association; her second was Craig Doerge, the longtime keyboardist for Jackson Browne and James Taylor. Woody Allen partially based the title character of Annie Hall on his nightclub touring partner Henske, who came from Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, like the Diane Keaton character.

What makes Henske important, though, is the way she stuffed old songs with a full-bodied humor and sexuality that was more in sync with the originals than the often pristine, bohemian-princess versions of her contemporaries. When she belted out a gospel song such as “Wade in the Water” or a blues like “Betty and Dupree,” there was nothing dainty about the need and belief she poured into her vocal. Yes, her performances were a bit brassy and over the top in that old Tin Pan Alley, show-biz way, but that voice was not to be denied.

Henske may have been forgotten, but at least she enjoyed a long, happy life with her second husband (who helped her to make two late-career albums in 1999 and 2004). Far more tragic was the life of Karen Dalton, possessor of another strong alto that she twisted into some of the ’60s’ most chilling renditions of the folk and blues canon. She only released two albums before her battles with addiction and the industry led to a withdrawal from public view and her 1993 death of AIDS-related illness.

This was especially heartbreaking, because the small amount of music she left behind is powerful indeed. “My favorite singer in the place,” Bob Dylan wrote about his early days in Greenwich Village, “was Karen Dalton. She was a tall, white blues singer and guitar player—funky, lanky and sultry. Karen had a voice like Billie Holiday’s, played guitar like Jimmy Reed, and went all the way with it.”

Recently there has been a campaign to revive her memory. The 2020 documentary film Karen Dalton: In My Own Time backs up Dylan’s assessment with enough music clips to show how striking she could be when she was on her game. Filmmakers Richard Peete and Robert Yapkowitz interview Dalton’s contemporaries such as The Journeymen’s Dick Weissman and The Holy Modal Rounders’ Peter Stampfel, as well as influencees such as Nick Cave and Vanessa Carlton, who attest to Dalton’s value. Also onscreen is Jill Lynne Byrem, who changed her name to Lacy J. Dalton in honor of her troubled friend before releasing 16 top-20 country singles in the 1980s.

More persuasive than the testimonies are the handful of film clips of Dalton’s live performances. A tall, lean woman with straight, dark hair that fell to her waist, she played acoustic guitar or banjo and sang in a voice that relied less on Henske’s power and more on the nasal, note-stretching drama of a Billie Holiday. When she sang “Turn the Page” or “A Little Bit of Rain,” respectively written by Tim Hardin and Fred Neil, her voice contained that late-night desperation when all the bars are closed, the lights are off and the fair-weather friends have gone home.

And when she reached back deeper into history for a blues number such as Leroy Carr’s “In the Evening,” or an Appalachian tune such as the traditional “Katie Cruel,” Dalton seemed unmoored from time itself. When her husky voice did its tug-of-war between desire and rejection, it could have been coming from any decade, any century.

One thing the film gets wrong is its depiction of Dalton’s second and last studio album, 1971’s In My Own Time. She wasn’t happy with it, and the movie’s commentary implies that the heavy-handed folk-rock arrangements obscured the singer’s gift. But if you listen to the album, reissued with nine bonus tracks by Light in the Attic Records last year, the arrangements are in fact quite tasteful. Produced by Dylan’s ex-bassist Harvey Brooks and performed by such friends as Band producer John Simon, Maria Muldaur guitarist Amos Garrett and soon-to-be Janis Joplin pianist Richard Bell, the playing nicely framed Dalton’s vocals without ever getting in the way.

The result is an album that should have launched her career to another level, thanks to knowing female takes on Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” and George Jones’ “Take Me,” a hymn-like reading of Richard Manuel’s “In a Station” and the definitive version of “Katie Cruel.” But Dalton turned down gigs, moved to the Rocky Mountains, declined to engage with the industry and fell away into obscurity.

What’s left are the two studio albums, In My Own Time and It’s So Hard to Tell Who’s Going to Love You the Best, her 1969, stripped-down debut (reissued in 2009 and 2015), and an ever-growing number of live recordings. The best collection of those live performances is the soundtrack for the documentary, which hasn’t yet been released as a stand-alone album. Next best is the two-CD and one-DVD set, Cotton Eyed Joe, recorded at a Boulder coffeehouse in 1962, when she was still optimistic and healthy. It includes examples of her ability to turn Ray Charles songs into front-porch picking numbers, and to transform a song about a “Mole in the Ground” into a prickly nightmare.

Less successful is this year’s live collection, Shuckin’ Sugar, recorded in Boulder the following year. Too much of this batch buries Dalton’s distinctive voice in conventional country and gospel harmony singing, or in laidback performances that drain the tension from her best singing. None of these records contain Dalton’s original songs, which she rarely shared with anyone else. But the movie ends with a rare radio recording of her composition, “Remembering Mountains.” The lyrics are very slight—fragmentary phrases about beauty, love and nature—but the music is intriguing. It suggests where her career might have led if it hadn’t been derailed by drugs and agoraphobia.

When Dalton died, her children discovered a sheaf of original song lyrics without any indication of the music that went with them. In the spirit of similar projects to resurrect the abandoned lyrics of Woody Guthrie and Hank Williams, guitarist Peter Walker commissioned 11 women to put music to the words for the 2015 album, Remembering Mountains: Unheard Songs by Karen Dalton. Sharon Van Etten handles the title track, and Isobel Campbell turns “Don’t Make It Easy” into a whispery blues. Patty Griffin supplies a Henske-like vocal to “All That Shines Is Not Truth.” The highlight of the collection is Lucinda Williams’ treatment of “Met an Old Friend,” a lament about a lost love and a refusal of everyone who offers help.

Another woman who made her second and last studio album in 1971 was Norma Tanega. Arriving in Greenwich Village from her native California in 1963—the same year Dalton arrived from Colorado—Tanega was soon strumming her acoustic guitar and singing in the local coffeehouses. She stood out in a number of ways. She was a gay woman, the daughter of a Filipino father and a Panamanian mother, and she was less interested in digging up old folk songs than in showcasing her own quirky originals.

Those songs were well worth hearing. While she was getting an MFA in painting at Claremont College, she had also taken enough music courses to be comfortable with unusual time signatures, unlikely melodic intervals and unexpected chord changes. But these tools never sounded stiffly academic, because she had a sly sense of humor and a gift for catchy tunes. The push and pull of her one and only hit, “Walking a Cat Named Dog,” was covered by everyone from The Jazz Crusaders and Art Blakey to Yo La Tengo and They Might Be Giants.

That song was inspired by her Village apartment building that didn’t allow dogs. So she got a cat and named it Dog. The incongruity of walking Dog, her little cat, on New York’s sidewalks tickled her so much that she reveled in the “happy, sad and crazy wonder” of it all, which was “choking up my mind with perpetual dreaming.” That carefree feeling of being in one’s mid-20s without responsibilities was reinforced by a skipping rhythm and bouncy melody that made a jubilant jump from “dream-” to “-ing.”

Arranger Herb Bernstein gave it a hooky harmonica intro and pizzicato strings, and soon the single was a top-25 hit in the U.S. and the U.K., and #3 in Canada. A 1966 album of the same name was soon released, and Tanega was off to England to promote it. There, on the TV show Ready, Steady, Go, she met Dusty Springfield. Within months, the two were a couple living in London. Over the next five years, Tanega wrote half a dozen songs that Springfield recorded, as well as songs for the two albums that Tanega planned for herself.

The first one, Snow Cycle, was never released, but two songs from it are included on the new, 27-track compilation, I’m the Sky: Studio and Demo Recordings, 1964-1971. Those numbers are trying too hard to fit into a concept album, but she sounds more relaxed on the second album, I Don’t Think It Will Hurt You If You Smile. Cut in London with producer Don Paul and multi-instrumentalist Mike Moran, it combines the breezy charm of her debut with more sophisticated harmonies. It’s an overlooked chamber-pop gem.

The anthology is oddly sequenced, so that the 13 tracks from the two released albums and the 14 demos are scrambled without chronological order. The booklet offers a brief bio, but not many session details. Though most of these songs are wrapped in baroque-pop arrangements, the core of them is Tanega’s modest soprano and acoustic guitar or autoharp, the tools of her songwriting and early coffeehouse performances.

Tanega vanished from public view as completely as Dalton, but under happier circumstances. When Tanega and Springfield broke up, the American returned to California and her first love, painting. In fact, the lavishly illustrated new book, Try To Tell a Fish About Water: The Art, Music and Third Life of Norma Tanega, has just been published. The color plates of her paintings and the oral history from her friends indicate that she had a productive and happy life in the four and half decades before she died in 2019. Whether on canvas or on wax, Tanega’s work was vibrant and unconventional, and it’s too bad the music industry was disinclined to share more of it.