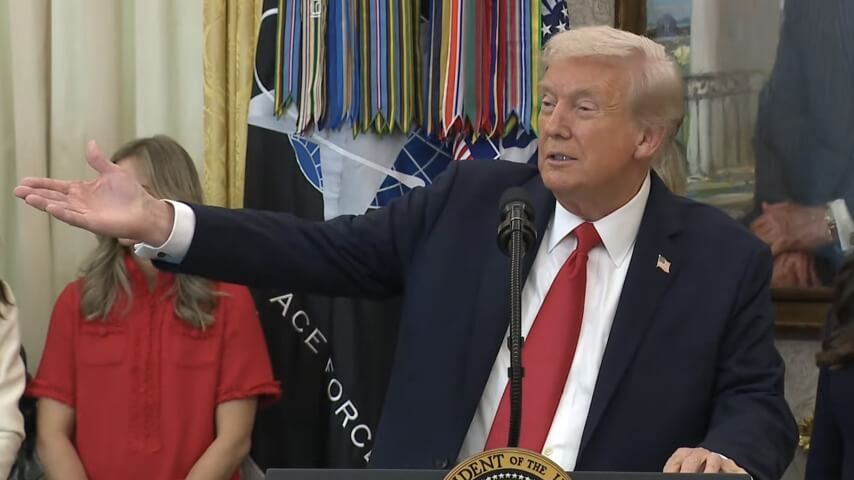

It’s hard not to presume that Donald Trump is a fan of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s 1969 hit “Fortunate Son.” If nothing else, the song has popped up often enough on playlists at Trump’s various events and rallies—in defiance of both John Fogerty’s own cease and desist requests, and frequent commentary pointing out the irony of a man who bone spurred his way out of service in Vietnam gravitating to a song railing against the inequities of its draft—to suggest he enjoys its iconic guitars, along with its presumably vague-in-his-brains associations with a war-time context. Still, it’s such a flummoxing song, lyrics-wise, for Trump to obsess over, that its latest use by his marketing wing—in a TruthSocial post where it was used to soundtrack the United States’ sudden attack on Venezuela in the early-morning hours of January 3, 2026—forces us to fall back on an old question that frequently crops up in discussions where logic is futilely deployed against this administration’s actions: Stupidity, trolling, or both?

We should start by acknowledging that the question is ultimately academic: Trump’s going to keep using the song, no matter what anyone says, because he wants to, and because there appear to be no levers of control that anyone who has access to them is willing to stand up and use that could actually force him to stop. In the light of that apparent, determined powerlessness, trying to figure out whether the man and his cronies genuinely don’t understand that “Fortunate Son”‘s anti-war meaning flies in direct opposition to this latest use, or whether said deployment is a deliberate effort to thumb their noses at the idea that art can have any inherent meaning whatsoever, or whether it’s really just about the pleasures of irritating people who demand some measure of logic or consistency from them is, in its own way, playing directly into the troll’s hands. The incoherence, to mutate an old catechism about Trump’s first administration, is the point.

And, really, it’s possible—nigh certain—that we’re overthinking this. Trump was, after all, 23 when CCR released “Fortunate Son,” and the song has been employed so aggressively in the Hollywood movies he obsesses over across the decades that it may simply now be lodged in his brain as “kick-ass war song,” with no further thought given. (See also his weird obsession with Apocalypse Now, where White House marketing has glommed on to the gung-ho aesthetics of portions of Francis Ford Coppola’s film while gleefully shucking them of their attached meaning.) The fact is, Trump came of age in an era where the cutting edge of American art was determinedly anti-war, which presents at least an ostensible barrier to his efforts to deploy that same art in order to feel like some kind of powerful, young, hawkish badass, while his military advisers Wormtongue their way around him, plotting their various global coups. Luckily for him, things like context and reality have always been easy for him and his administration to dodge; on that level, who are we to say he isn’t the most fortunate son of all?