One of the rare, decidedly unexpected upsides of the pandemic has been the surreal fluidity of time. With 9-5 clock-punching becoming a thing of the past for many of us, it was easy for days to slip into nights and vice versa, so seamlessly that you could easily find yourself wide awake at 3 a.m., hypnotically scrolling through countless random cable channels or streaming services, in search of something new to watch. And until you end up drifting through the truly strange late-night possibilities, you never really know what long-buried cinematic gem you might uncover. True visual oddities like director James Szalapski’s curious musical documentary from 1976, Heartworn Highways, which has been popping up lately at hours when most of us used to be peacefully asleep. Some might have seen it; many have not, and it’s not an easy movie to explain.

There is no real linear plot to Heartworn Highways, outside of following once-incarcerated country renegade David Allan Coe as he drives his own tour bus to the Tennessee State Prison, where he plays a quirky but convivial concert for inmates. But it’s the other footage that Szalinski gathers along the way that’s simply magical, capturing the Texas Outlaw Country movement in its infancy, via: a young Guy Clark, plying his trade as a luthier; Townes Van Zandt, spinning yarns like a talk show host on his bucolic farm; other upstarts like Steve Young, Rodney Crowell and even Charlie Daniels, playing a high school, and then, later in the inexplicably sequenced clips, a spider-limbed young disciple of that songwriting school, his long hair practically obscuring his face and a cigarette dangling Ron-Wood-dangerously from his lips—future Grammy winner Steve Earle, 21 at the time, playing his own early material like “Elijah’s Church,” but obviously in reverent awe of his mentors. He might be sitting at the same Nashville kitchen table with the late legend Clark and company in the scene, and sharing the same bottle of inspirational booze (“Now that’s vodka!” he rasps after a swig, before leading a seasonal singalong of the traditional “Silent Night”), but it’s clear that he’s paying studious attention. Because you just don’t get access to those kinds of teachers anymore.

Why did his elders accept this neophyte, warmly welcome him and take him in? Earle’s still not sure. “But I think part of it was, I was persistent, and I probably wouldn’t let ’em ignore me,” he reckons. “So I think they had to admire that, because they had to do that, too, to get where they were at the time. And another part of it was, Townes tended to put me through more hoops, because he was pretty hard on himself—he was his own worst enemy, in many ways. And with Guy, it was more of a direct apprenticeship, because you could ask him questions and get a straight answer. Whereas Townes would give you a copy of [Dee Brown’s] Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and tell you to go read it. But Jerry Jeff was just Jerry Jeff—he was good at what he did, and he knew he was Jerry Jeff Walker. But when he ran across something he liked, he championed it.” And Clark, in turn, picked up said trait from him, he believes. “Because Guy literally bugged Pat Carter to death until he signed me to my first publishing deal, at Sunbury Dunbar, so I wrote for the same place Guy did. So it was just one of those things—I was just the kid that showed up.”

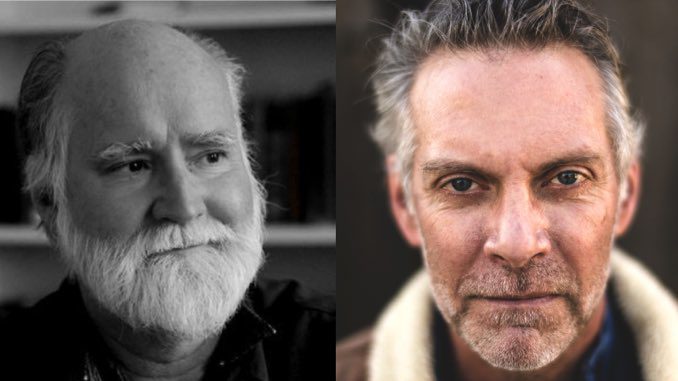

And in the process, the 20-something Earle, now 67, learned respect for The Song and its practitioners, and it shows on the soundtrack, his first-known recordings. And long after he broke into the alt-country business with his definitive Guitar Town debut from 1986, he went on to pay dutiful tribute via collections of covers that tipped the hat to his crucial tutors, who look barely out of their teens themselves in Heartworn Highways (an expanded DVD edition of which features bonus scenes of him crooning “Darlin’ Commit Me,” “Mercenary Song,” and—with another young up-and-comer at the time, Rodney Crowell—“Stay a Little Longer”). First came the Clark-honoring Guy in 2009, then Townes 10 years later, the third entry in Earle’s trilogy, Jerry Jeff, his 22nd overall. It’s a 10-track nod to another telling musical influence, Jerry Jeff Walker, a New York-reared folkie who settled in Austin, began running with cutting-edge tunesmiths like Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson, but succumbed to throat cancer in 2020 at 78 (Van Zandt died in 1997, Clark in 2016). And although Walker doesn’t figure into Heartworn, the obscure old film and freshly cut new album nicely complement each other. They capture a bygone era when composers considered their craft to be some sort of alchemy, and a perfect song to be worth its emotional weight in gold.

Thinking back on his youthful mid-’70s days on Music Row, the San Antonio-raised Earle gets wistful. He’d first discovered Walker at 14, when his high school drama teacher gave him a copy of the artist’s classic “Mr. Bojangles,” which Earle covers on Jerry Jeff, along with “Gettin’ By,” “Little Bird,” “My Old Man” and “Hill Country Rain,” the tune he chose to perform at a life-celebrating concert last year in Luckenbach, Texas, organized by Walker’s widow, Susan, alongside fellow fans Emmylou Harris and Jimmy Buffett. The whimsical “Mr. Bojangles” not only caught the kid’s attention, but also gave him something to aspire to. And soon he was living in Nashville, palling around with other scrappy hopefuls like John Hiatt, and testing out originals at smoky coffeehouses. It might be tough to picture, but he actually sported a beat-up black cowboy hat back then, with a beaded band, which was what initially caught Clark’s eye in a club. “He just walked over and said, ‘I really like your hat,’ and that was the first conversation that we ever had,” Earle drawls, chuckling. Next thing he knew, he was playing bass in the man’s band, co-writing with him, and then helping him record his landmark Old No. 1 debut in ’75.

The newcomer also began working with Van Zandt. But he makes clear the fact that Walker was always his first and foremost stylistic influence. He wanted to be Walker, he swears, and he grew his hair appropriately hippie-cosmic long. Walker, in turn, came to trust Earle enough to make him his designated driver, ensuring he got home safely each libidinous night spent on the town. The disciple watched the master casually hitchhike to various distant gigs; he did the same, admittedly somewhat naively, and occasionally found himself in some scary situations. “And yeah, it happened—if you hitched as much as I did, it happens,” he says. “I ran away from home when I was 14, and I had some people tell me once, ‘Hey, kid! Get out here and ask for directions!’” He sighs, somberly. “I fell for it. And they drove away with my guitar. So hitchhiking wasn’t for everybody, but it was for Jerry Jeff, and it was for me, and it was for Townes at one time, too. I don’t think Guy ever hitchhiked anywhere—Guy always had a VW that ran, and the rest of us didn’t. And Jerry Jeff actually toured on a motorcycle for a few years. It was a Harley-Davidson, and whenever it broke down, he would hitchhike.”

On paper—and in Heartworn Highways—that halcyon era appears picture perfect. But Earle is quick to point out that when it came to securing a recording contract, he was far from an overnight sensation. He’d been in town for 12 years without a nibble from a label, and he eventually put a rockabilly trio together to land a deal with Epic, for whom he tracked a full album called Cadillac (later sliced and diced as Early Tracks to cash in on Guitar Town’s surprise success). “I had four singles released on Epic, two charted, two didn’t, and none of ’em charted high, so they dropped me,” he recalls. In between, he cut four sides with producer Emory Gordy, utilizing a Duane Eddy-booming guitarist named Richard Bennett, and his trailblazing new take on country clicked perfectly into place, earning him a coveted slot on the MCA roster. “And Epic did what they did—they owned those masters, and when Guitar Town went to number one, they had the right to release them.”

Earle has a passel of wild Walker yarns, many experienced in person. He still loves retelling how the vagabond artist urged an unknown Alabama-bred artist named Jimmy Buffett to hop in his ’47 Packard and drive to Key West, thereby setting the stage for Buffet’s whole Margaritaville sea-breeze sound and restaurant empire. “And not long after that, Jerry Jeff got run out of Key West, but Jimmy stayed for a while,” he adds. “And I knew about Guy Clark because there were three of his songs scattered across Jerry Jeff’s two albums he made for MCA—the only way I heard his songs was Jerry Jeff Walker singing ’em. He was very generous about that, making people aware of the songwriter, and the first time I ever heard Tom Waits’ name was from him. He had been all over the place, and he just knew.” Because Walker was a dedicated interpreter of his peers’ efforts, too, a bonus-track edition of Jerry Jeff includes three non-Walker selections—Ray Wylie Hubbard’s “Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother,” Michael Burton’s “Redneck Lament” and David Gilstrap’s “Rodeo Cowboy.” “But the basic 10-song album is all songs that Jerry Jeff wrote, dating back to his ATCO/Vanguard days,” Earle explains.

Watching Heartworn Highways and its incredibly powerful moments like Clark crooning “L.A. Freeway,” then harmonizing with Earle on his then brand-new “Elijah’s Church”—their voices still light and crystalline, not having lowered to the Nick Nolte-gravelly tones they would both assume later—you simply have to stand in awe at the sheer magnitude of a lovingly crafted folk/country song. Earle—who went on to author plays, short stories, host radio shows and podcasts, and act in hit TV series like Treme and The Wire—still holds the art form in the highest esteem, and he rhapsodizes at length about such perfect examples as Clark’s “The Randall Knife,” a reflection on a parent’s passing that can move the average listener to tears. “It took Guy a long time to write that song,” he sighs, still awed. “And just like the song says, he had to give it a certain amount of time before he could deal with it. So that’s what he did. And that’s what he wrote.”

Similarly, he says, everyone from random truck drivers he’d meet to the Man in Black himself, Johnny Cash, went out of their way to compliment him on the Guitar Town ballad “Little Rock and Roller,” an ode he penned for his then-toddler son Justin Townes Earle (who tragically overdosed in 2020 from cocaine laced with deadly and addictive fentanyl, now a national opiod scourge that’s 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times as strong as heroin; he honored his late son by cutting a tribute album of his songs last year called J.T.). “And that’s when I figured out what this job was,” he concludes. “I wrote ‘Little Rock and Roller’ because I was on the road all the time, and I missed my kid, but what me, Johnny Cash and a truck driver have in common? We all miss our kids on the road. So it doesn’t matter so much what a song means to me as what it means to somebody else, and that’s what the job is.

“The job is about empathy, and it’s about what you have in common with the audience. It’s not about how cool you are.”

Jerry Jeff

is out now on New West.

Watch Earle’s 2022 Paste session below.