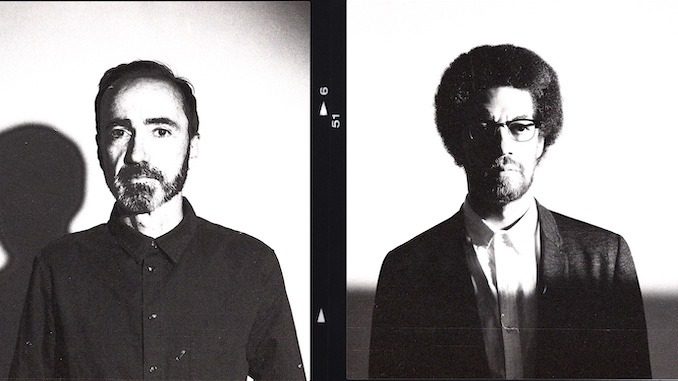

Shane Fogerty and Tyler Fogerty both happily admit to being big fans of campy 1960s and ’70s cartoons from that animation powerhouse Hanna-Barbera, and they’re well aware of its signature Lippy the Lion and Hardy Har Har series, featuring a spunky king of beasts and his conversely cowardly hyena companion. But said whingeing character had nothing to do with the kooky moniker the musical siblings chose for their ’60s-and-’70s-retro band Hearty Har, an apple that couldn’t have fallen farther from the metaphorical tree — given that their father just happens to be Creedence Clearwater Revival legend John Fogerty, who is now 75.

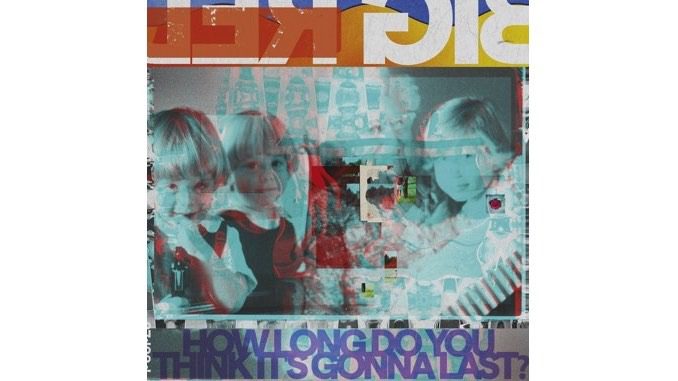

In fact, there’s none of dad’s signature swampy choogling in any of the dreamy, often Neo-psychedelic grooves of Radio Astro, the brothers’ debut disc, from the opening New Christy Minstrels-fluffy “Radio Man” through the Stax-Volt-gritty “Calling You Out,” a Morricone-trumpeted instrumental called “Canyon of the Banshee,” the sultry R&B raveup “Get Down,” to a sinister, vintage-novelty-hit-echoed “Boogie Man.” The brothers’ latest single, “Fare Thee Well,” is nothing like the traditional folk its title suggests—it’s twinkling with Peter Max-vivid keyboards and a tinny-but-booming guitar riff that sounds like Link Wray trapped inside a Mason jar. Naturally, a comic canine just couldn’t cut it as any kind of apt sonic descriptor.

Hearty Har occurred to the Thousand-Oaks-based Tyler, 28, out of the blue way back in 2012, when he and Shane, 29 (who lives in nearby Sherman Oaks), were accompanying their solo-touring father, who was playing a huge Hyde Park concert in London alongside Bruce Springsteen. And it was just one of countless truly surreal moments to which they had become accustomed growing up in the shadow of such a rock legend.

“It was a summer where a lot of events like that were happening,” recalls Tyler, who shares vocal and guitar duties with Shane. “And we were in college and we’d just parted ways with this old band we were in, so throughout that whole tour I was trying to think, ‘What’s the next step? What are we gonna do?’” The answer came to them in serendipitous fashion, while quietly sitting backstage at the show, when the E Street Band suddenly formed a pre-show circle around them and began singing “When the Saints Go Marching In” as a vocal warm-up. “And we were like, ‘What?! This is crazy! What is this cosmic little event?’,” he adds. “And it made me think, ‘Man—I am so lucky to experience these kinds of things, but don’t let it get to your head. Just have a good laugh and a good spirit about it.’” As in, Hearty Har. “It just popped into my head, and I thought, ‘That’s it! That’s what I’ve been looking for!’”

Oddly enough, the pun stuck, and seemed to perfectly fit their new approach and Nudie-suit-bedecked style, which owes as much to Gram Parsons as it does to obscure old delights like The Honeycombs and their buzzy Joe Meek production. “And that’s why the name’s not Hardy, with a D, but Hearty, like it’s a really fulfilling thing,” Shane chimes in. “We just really liked that play on words.”

Watch the exclusive debut of the video for “Fare the Well”:

Paste: At what point, growing up, did you finally start to realize, “Whoa! Our dad is fucking awesome!”

Shane Fogerty: In our teenage years, when I was 12, maybe. Older kids would come up to us at school, and they had discovered Creedence, I guess, because they’d say, “Dude, your dad is so cool! And his concerts! Are you gonna go do all of that? They’re probably smoking weed at his concerts! That’s just so cool!” And I feel like at that point, I thought, “Yeah. Okay. It’s cool for my dad to be a rocker—that’s a thing to be proud of!”

Paste: Who joined him onstage first?

Shane: I think we might have done it at the same time. But then I stuck with it> I kind of just gradually graduated into his band, so now I play guitar in his band. When we get to play.

Paste: Does Tyler join in, too?

Tyler Fogerty: Yeah, sometimes. But I just do some singing.

Paste: How old were you when you joined, and what were some amazing shows you played, where you were, indeed, Rockin’ all over the world?

Shane: I was 13 or 14, and the most memorable one I think I was 15, and we did a show at the Royal Albert Hall, and I got to go out and play the intro to “Up Around the Bend.” I was so scared I was shaking. And I knew what the Royal Albert Hall was, because I had watched that Cream reunion DVD, so it was fresh in my mind, and also the Beatles song, “A Day in the Life.” So that was a really crazy moment for me as a kid—it felt so incredible, and I just felt so lucky to be able to do that.

Paste: It’s strange to note that CCR’s swampy voodoo sound coalesced out here in the non-bayou-based Bay Area. It’s pretty remarkable.

Shane: Well, it was in our dad’s imagination, what he could dream up and what inspired him. It was his muse—the mysterious Louisiana bayous.

Paste: But you guys sort of resisted music at first? And Tyler started exploring other arts?

Tyler: I do like photography and graphics, like photoshopping and collaging stuff. And I do all the artwork for the band, too. But going back to the question of copying his sound, I feel like that’s just the obvious thing that you shouldn’t do. Especially knowing other sons of famous musicians. Like, why would you want to do the same sound when it’s already so well done, you know? It’s not really adding anything—it’s just kind of cheapening it. But I know a lot of people expect that, and they wanna hear that, and it’s been interesting having to deal with those people and trying to tell ’em, “Well, that’s not what I am passionate about. That’s not what I wanna make and hear. I’m sorry—I’m not just a replica of what came before.”

Paste: Flashing back to your Hyde Park epiphany, what kind of band were you in before?

Tyler: It was me and Shane and a drummer and a bass player, and it was more kind of bluesy rock, I would say. And me and Shane weren’t really the songwriters—we hadn’t evolved into that yet. It was more the bass player who was calling the shots. And then we kind of dabbled with spaghetti Western around that time, and out of that we started a kind of folk-rock thing, and the first couple of songs I was writing was on weird instruments—I fused a guitar with a harmonium and a charango, and it was more mellow, and then it gradually evolved into a more fully-fleshed-out rock kind of sound.

Paste: Who plays keyboards on Radio Astro, and what kinds do you use?

Tyler: A whole bunch. Me and Shane kind of split the duties of that. We have a farfisa, a Vox Continental, a mini-Moog, and a real Mellotron. We don’t have a Fender Rhodes—we have a Wurlitzer, plus a harpsichord, a harpsiphone, a synthesizer.

Paste: So you’ve become instrument geeks—you collect.

Shane: Yeah. And we have been for a while. When we’d go on tour with our dad in Europe, Brazil, North America, we’d just go into music shops and check out what was going on. And that’s where, in South America, I got the charango, and Tyler got a charango, too. And there’s also one that’s like a banjo-ukulele—it looks like a banjo, but it’s high strung like a ukulele, and it’s crazy and sounds like a mix of the two instruments. It’s from Brazil. But just going around the world on tour and going into music shops and checking out all these wild instruments has been really cool. There are charangos that are made out of armadillo shells.

Paste: How would you tell dad? “Uhh, we might have to miss soundcheck—we’re going off to another music shop.”

Shane: He’d be like, “I’m going, too!” And it would be good if he went, because then you’d be more inclined to get stuff.

Paste: What was the hardest instrument to track down?

Tyler: Actually, it’s this thing called a clavioline—it’s like the first synthesizer, and it was made in the late ’40s, and it’s the solo on “Runaway” by Del Shannon. And his clavioline was modified by this guy named Max Cook, and it’s got a built-in spring reverb, really crazy tube reverb that they used to use in cars. And this clavioline that I got was from somebody that knew Max, and taught him the secret of how to modify it—it’s one of four still in existence.

Shane: And it sounds incredible, real super-meaty and aggressive. And it’s like, “Wow—this thing was in the ’40s?” Because you plug it in through some loudspeakers, and it fucking RIPS.

Paste: And your production seems beamed in from another era, too. Did you study old manuals or techniques?

Tyler: Not really. I think it’s more about just listening to a lot of old recordings and just acquiring cool stuff. And then just knowing how to tune the sound when you’re recording, how to get it really close to what you like. Like, the buzzing that you hear on “Can’t Keep Waiting” isn’t actually a guitar—that’s the clavioline. And there’s a lot of modulation and reverb that you hear, so if you listen close you’ll be like, “What the hell is that?” I like to keep that kind of mystery going.

Paste: How many guitars do you guys have?

Tyler: I have maybe seven or eight guitars, but our dad has so many that we can borrow. He’s got that electric guitar thing down pat. But most of the tracks on this album are our guitars—a Rickenbacker, a Vox, a ’66 Strat, a Guild 12-string, a Martin six-string.

Paste: What are some of your favorite albums for reference points?

Tyler: That’s really hard. Because it changes a lot. You’ll play a record so much, and then you kind of like don’t listen to it for awhile. Like, “Village Green Preservation Society”—I’ve listened to that so many times, and I personally love it. But I can’t listen to it that much anymore.

Shane: If I really had to pick—and this has always been one of my favorites, even though it gets overplayed a lot—“Led Zeppelin III.” And I fucking love The Rolling Stones’ “Beggars Banquet.” That whole era, from ’68 to ’73—there were such good albums. And maybe Dennis Wilson’s “Pacific Ocean Blue”—I love that record. We both love Dennis Wilson. And we love Jeff Lynne, too. “On the Third Day” is just awesome.

Paste: But Hearty Har has successfully created its own sonic world on this album. Which has absolutely nothing to do with your dad’s.

Shane: And I like that. I think there are little flourishes here and there, maybe. But it’s our own thing.

Tyler: One sound that I wanted to utilize, though, was, he has all these old custom amps here, and one time I snuck into the room where they were and I brought one out. And it has his vibrato thing and just feeds back incredibly , and it works with any guitar. Because he does that solo on “I Put a Spell On You,” and I want to utilize some of that feedback one day, maybe do some harmonies with it. Because it is SO cool.

Paste: Who writes the lyrics?

Tyler: We split it. It’s kind of like who sings the song will write the lyrics.

Paste: Well, you can be proud that Radio Astro is a fully-realized vision. But you did have a few years since Hyde Park to figure it out.

Shane: It was a long labor and a learning process for us. It was really stressful, all the way up to the mixing. We were like, “Does this even sound good?” We thought it did, but we really didn’t know. And we kind of lost a lot of band members along the way—they couldn’t see where we were going, they didn’t believe it like we did. And that was hard, too—people getting frustrated with you. But we try to bring everything together into our, uhh, hearty pot of stew.

Paste: What lessons did your father teach you? And what was his best advice?

Tyler: Just that it’s life and death. If you’re gonna do it, it’s like life and death—you’ve got to treat it as seriously as possible, because it either sucks or it’s great. You should have a very intense work ethic, but you should have an awareness of what you’re doing—I think that’s what he taught us.

Shane: Yeah. And respecting the process of practice and performance, and not getting too messed up to perform. Like, he doesn’t drink before shows, ever. He’s very strict about that, and he doesn’t want anyone in his band to do it, either. He’s like, “Why? Why would you wanna do that? This is your moment, and you wanna cloud or dilute that? You’re gonna drink, then it’s not gonna be everything that it could be!” He’s big on that, just on the performance side—not being under the influence of anything.

Paste: What have you learned from the pandemic? And how dark are any new Heart Har songs?

Tyler: Well, “Waves of Ecstasy” was the only one written in the pandemic. And for me, it’s put me more in touch with the spiritual side, and also the softer side of my voice, like he falsetto on “Waves.” This album was pretty rocking and immediate, and now I wanna explore something more complex, stuff that’s not as obvious.

Shane: I think that for my new writing that I’ve been doing during this time, a lot of it has been more…uplifting, I guess? It just seems like everything I want to sit down and start work on is coming out pretty optimistic-sounding and very positive. So I feel like I wanna make more of that stuff, but also keep it more in our realm of spooky and mysterious.

Paste: Final comment on Hearty Har—it’s good that it took you this long to release your debut. Because the time just feels right.

Shane: Yeah. And it was out of our hands, almost.

Tyler: There was kind of an intense moment. We were in New York two falls ago, and the album was pretty much done except for “Waves of Ecstasy.” And we were like, “What the hell are we gonna do?” Because we knew what it was, and we had put everything into it, and I was getting really worried, like, “Is this something that’s even gonna work? Because I don’t know if I can keep producing this kind of music with nothing happening—I’ve got to make something happen.” I was really flustered. But then the next day, our mom and dad had a dinner with this guy David Spero and a couple of people from BMG, and the next morning we were having a meeting with BMG. And it was like, “Wow!” It just kind of happened out of nowhere, at least the first sep, It was really weird.

Shane: And at he end of that year, when we were actually in the New York BMG offices and meeting David, thats’s when it really all started happening. “We were like, “Okay. This is REAL now. This is gonna be a thing.”