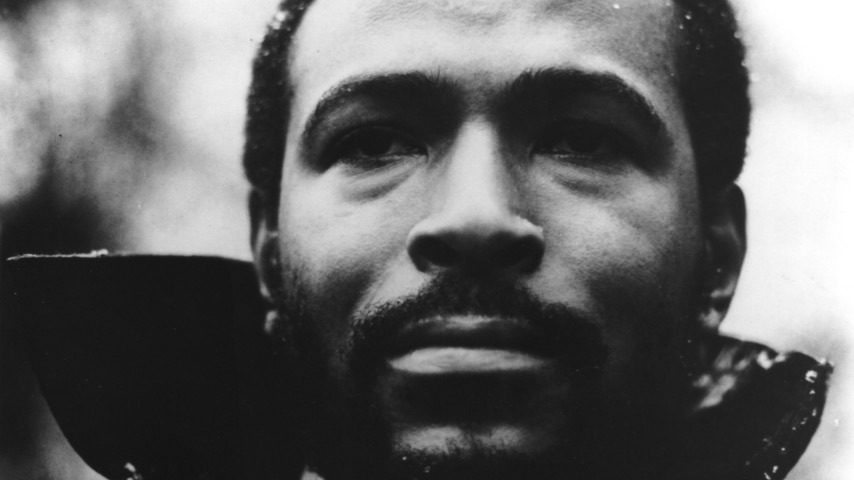

Marvin Gaye recorded the song “What’s Going On?” in June and July of 1970, though it took six months of wrangling with the conservative leadership of Motown Records to get it released as a single the following January. When it finally emerged, it resonated with an America unsettled by war, pollution and racism, an America hungry for the spiritual uplift and social action that the Black church promised—and that a new generation gave a new immediacy. As a result, this song’s blend of gospel tradition and soul-jazz experimentation topped the R&B charts for five weeks and rose to #2 on the pop charts. When people do those lists of the “100 Best Songs of All Time,” this single is usually in there.

It opens with the sounds of a party getting started as old friends greet each other until Eli Fontaine’s soprano sax solo ushers in the song itself. Gaye’s tenor is simultaneously relaxed and immense, as if his confidential purr had been expanded to fill an airplane hangar. It’s the voice of a preacher presiding over the funeral for a young soldier who died in Vietnam: “Mother, mother, there’s too many of you crying,” he sympathizes. “Brother, brother, brother, there’s far too many of you dying.”

Over the rippling rhythm of the great Motown bassist James Jamerson, finger snaps and Gaye’s own slapping on a cajon (box drum), the singer articulates the question on every mind in the congregation: “What’s going on?” Now it’s half a century later, and America is more unsettled than ever, still waiting for an adequate answer to that question. What could be more relevant today than Gaye’s plea, “Picket lines and picket signs, don’t punish me with brutality”?

Many of today’s songwriters are sure they have the answer to Gaye’s question, but they are usually too glib and facile to have much credibility. If the solutions were as obvious as hip-hop slogans, rock ’n’ roll hooks and pop-diva platitudes seem to suggest—or as their often predictable music promises—our problems would have been resolved by now.

Gaye himself never fell into that trap; he was less interested in offering easy answers than in identifying the issues, portraying the conflicting sides and capturing the urgency of the struggle—and not just in words but also in the jazzy, expansive music that provided plenty of room for reflection. That’s why his song—and the album of the same name—has outlived the specific events of his day to apply to every era, even ours.

Gaye was a master of what I consider the secret of soul-music singing: the ability to sound vulnerable and dignified in the same moment. It’s not easy to project weakness and strength simultaneously—and most vocalists emphasize one or the other. But artists such as Gaye, Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin, Dionne Warwick, Smokey Robinson and Luther Vandross resolved this paradox by acting as if revealing one’s hurt and doubt required an act of courage that one could be proud of.

They were right, of course, but it’s easier to describe this combination than to project it in song. It requires a master actor who’s also a master singer. In an era when popular music has bifurcated into macho and emo branches, the R&B blend of pain and poise is harder to find. But it’s still out there if you search for it.

So where are the Marvin Gayes and “What’s Going On?”s of our day? You won’t find them at the top of the charts, but you can still discover them at the margins of the music industry. This year, for example, has seen smart, probing albums full of gospel and soul roots, full of hurt and pride, from John Legend, Gregory Porter, Aloe Blacc, Bettye LaVette and Shemekia Copeland.

Of those five albums, however, only Legend’s has reached the top 40 of Billboard’s U.S. pop or R&B album charts (at #19 and #13) and none has yielded a top-40 single on either chart. Despite their limited sales, these recordings speak to the current moment in a special way. They pull from both the street and the church to offer challenges and consolations, anguished vocals over rousing piano chords and questions without easy answers.

We discussed Porter’s terrific album, All Rise, in an earlier column. Legend’s latest album, Bigger Love, reminds us of his immense debt to Gaye. You can hear it in the relaxed vocals, the hangar-sized reverb, tasteful strings, finger snaps, gospel piano and rippling polyrhythms.

Legend has spoken out on social issues on previous recordings—most notably his 2010 collaboration with the Roots, Wake Up! But this one is focused on romance—more like Gaye’s underrated In Our Lifetime album than What’s Going On. This is not an album of new love but of long-term love—it’s not about how to ignite a fire but how to keep the embers glowing. It’s not that one kind of song is better than the other, but both experiences deserve musical exploration, and pop music gives us more than enough new-love songs and not nearly enough old-love songs.

Legend is a limited lyricist with a weakness for schmaltzy platitudes, but he’s a terrific singer and composer, able to create instrumental and vocal arrangement that evoke the complicated feelings of an ongoing relationship that the words merely hint at. One reason Legend can do this is that he draws from the entire history of soul music—expertly recreating his quotes and bending them to his own purposes. The album begins with the “Shoo-ba-be-lop” intro of the Flamingos’ immortal 1959 single, “I Only Have Eyes for You.” “Remember Us” nods to Al Green, while “Focused” and “U Move, I Move” nod to Prince. And everything seems to echo Gaye.

What would Legend sound like if he were a better lyricist? He’d probably resemble Aloe Blacc on the latter’s new album, All Love Everything. When Blacc sings about “Family,” for example, on the disc’s first track, he finds vivid images to describe himself as both a child (“Still got this scar here on my knee/ From chasing trouble with the big kids on my street”) and as a parent (“I read my little ones to sleep/ Put my face right next to theirs to feel them breathe”).

That origin story is the foundation for a collection of songs about the struggle of a young man and his home boys from a poor neighborhood trying to make their way in a world stacked against them. “I remember the days when we had none/ Trying to fight through the waves,” he sings in Gaye-like tones on “Glory Days” over a Babyface-like acoustic guitar and a push-and-pull beat. But when the horns come in, he declares, “Welcome to the glory days.”

On the song “Harvard,” he sings, “I ain’t got no big degree/ Everything I know/ I learned it on these bitter streets.” When he borrows the title “My Way” from Frank Sinatra and Paul Anka, he shifts the perspective from the penthouse to the basement apartment. Over an infectious, gospel-soul snap-along, he declares, “I’ve been suffering at a job/ In a world that tries to own me,” but insists, “I’m going to do it my way.” If this were 1970, Blacc would be a huge star. In 2020, he’s buried treasure waiting to be dug up by the inquisitive.

If Blacc’s social commentary is couched in the terms of the marginalized narrator fighting his way into a successful life, LaVette’s observations are framed by the struggles of women to hold their own in lopsided relationships. The veteran soul singer didn’t write any of the songs on her new album, Blackbirds, but she organized the project around songs associated with African-American female singers. The title comes from the Beatles song, “Blackbird,” which Paul McCartney wrote as a salute to such singers. The album’s other eight songs were recorded by Lil Green, Dinah Washington, Della Reese and the like.

Billie Holiday’s classic “Strange Fruit” is the most explicitly political track. This 1939 protest against lynching—and by implication against all racist violence—was a weary lament on Holiday’s recording. In LaVette’s slow-blues arrangement, it becomes a furious indictment—her dark alto stabbing as sharply as Smokey Hormel’s guitar fills and Leon Pendarvis’s piano chords.

The politics are more implicit on the other songs. The album opens with “I Hold No Grudge,” which Nina Simone recorded in 1967. On the surface it’s addressed to a cheating man who asks for forgiveness, but it could just as easily be aimed at any employer or institution who treated her wrong. No matter who’s on the receiving end, the message is double edged: I’ll forgive you this time, but I’ll never forget how you did me and don’t even think about doing it again. When LaVette sings, “A woman who’s been forgotten may forgive, but never, never forget,” the instruments drop out so she can stretch out the two “nevers” in a scratchy wail that would give any adversary pause.

She delivers the same message with the same throat-twisting threat to the same class of betrayers on “Book of Lies,” a Ruth Brown B-side from 1958. LaVette celebrates her ultimate triumph over every obstacle by transforming the McCartney title track from a third-person observation into a first-person confession. The Beatle used a lilting, happy-go-lucky tune to encourage the blackbird to “take these broken wings and learn to fly.” LaVette slows the song down to explain the painful process of how “I took my broken wings and learned how to fly. All my life, I have waited for this moment to arrive.”

Like LaVette, Shemekia Copeland leans on the blues half of rhythm & blues even as she marries that sound to edgy Americana songwriting. The opening track on Copeland’s new album, Uncivil War, finds Americana star Jason Isbell adding hair-raising blues guitar to “Clotilda’s on Fire.” The song tells the story of the last slave ship to arrive in the United States, arriving in Mobile Bay in 1959, 50 years after importing slaves was outlawed, only to have the captain burn his ship to destroy the evidence.

The song was co-written by Copeland’s manager John Hahn and her producer Will Kimbrough. Among the duo’s other contributions are the Staples-like Civil Rights anthem “Walk Until I Ride”; the anti-one-percent blues-rocker “Money Makes You Ugly”; the gun-control anthem “Apple Pie and a .45”; and the string-band title song, which acknowledges how the conflicts of the 19th century Civil War still haunt us today. Other songs are taken from the Rolling Stones, Junior Parker and the singer’s late father Johnny Copeland. Guests include Jerry Douglas, Sam Bush, Duane Eddy, Webb Wilder, Kingfish and Steve Cropper.

Though her daddy was a Texas bluesman, Shemekia grew up in Harlem as a funk and hip-hop fan. Her immense soprano and genealogy got her a record contract in the blues world at 18. But she didn’t break away from the usual blues formulas till 2015 when she started blending blues vocals with Americana songwriting, leading to arrangements that split the difference. That year’s Outskirts of Love signaled the new direction; 2018’s America’s Child was her masterpiece, and this year’s Uncivil War is her political manifesto. Though her opinions are strong, she never comes off as preachy, thanks to the welcome doses of humor and funk.

That was Gaye’s lesson for all of us. America’s problems can’t be ignored, but neither can they be simplified into bumper stickers or tweets. They need to be acknowledged in all their enduring complexity and must be confronted with as much feeling as thought, as much hope as anger and as much dignity as pain. “You know we’ve got to find a way,” Gaye sang 50 years ago, “to bring some understanding here today.”