SongWriter

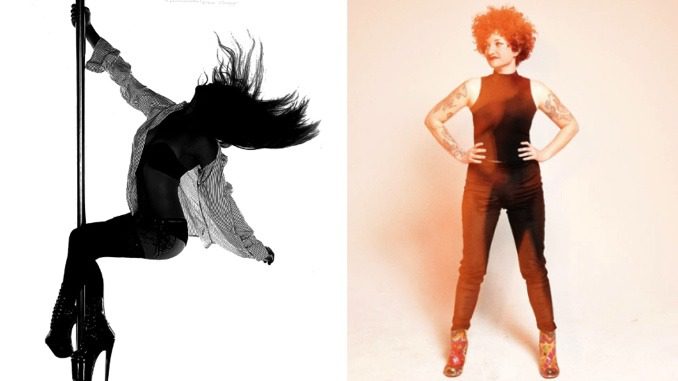

is a podcast that turns stories into songs, featuring David Gilmour, Joyce Carol Oates, Amanda Shires, Mary Gauthier, Roxane Gay, Susan Orlean, and Steve Earle. You can hear an exclusive preview of next week’s episode featuring a brand new song from Carsie Blanton, only at Paste.

Social worker Zelda used to work as a stripper, and she sees striking similarities between the two jobs. The patrons of the club in New Orleans where she danced often told her things that they had never told their wives and girlfriends.

“It’s the same thing. You’re paying for the hour, you’re telling deep, dark secrets,” she says. “You’re having that undivided attention and being heard.”

Zelda, who asks that her given name not be used for privacy reasons, said that she began stripping after she got a PhD in educational psychology and couldn’t find a job in academia.

“I was raised in a very Christian, evangelical, fundamentalist home, but I had been a trained dancer since I was in ballet since I was three years old,” she says. “I was also a trained aerialist at the time, and I thought, ‘You know what? I can’t get a job. I’m going to try this club thing.’ At 31 years old!”

Though Zelda found the work demanding, and sometimes degrading, the money was very good. Zelda also discovered that her earnings were often less about taking her clothes off than about being a good listener. Given her background in psychology, this came naturally—she was particularly adept at selling time in private “champagne rooms.”

“The most expensive room for an hour at the club was, I think, $6,000?” Zelda says. “For one hour, that’s no sex. And they’d pay it! And honestly for the most part, in champagne rooms they literally just wanted to talk. Or take a nap.”

Over time, though, Zelda’s work began to take a toll on her mental health. Thinking about next steps, she realized that the skills she developed at the strip club could be repurposed. She went back to school for a masters in social work, and now works in hospice.

“I absolutely love the field of hospice. We’re all going to die. No one gets out of here alive. And recognizing that and accepting it with grace helps you live the best life you possibly can,” Zelda says. Reflecting on her own life, Zelda tells me that there is no comparison.

“I am far happier now, making a fraction of the insane cash I used to make, because I’m stable, I’m healthy, I sleep,” she laughs.

Songwriter Carsie Blanton wrote a song in response to Zelda’s story called “Into the Light.” Carsie lived for years in New Orleans, and says that the city is deeply connected both to life and death.

“It’s sort of decaying and coming to life at the same time,” Blanton says. “It’s at risk of flooding and being under water all the time, and there’s always these parades that come through the city all the time. It reminds you of death, but also of life.”

Blanton, who is a passionate socialist, sees lots of connections between social work, sex work and music. In each job, she observes, the financial exchange hinges on the intrinsic value of human connection.

“What they’re really saying at the CD table and at the strip club and when they go to grief counseling is: Witness me. Let me tell you my story. Give me your attention. Listen to me,” says Blanton. “Whether because you’re a beautiful woman who’s naked or because you wrote a song they liked.”

This has become even more essential during the pandemic. Blanton describes the first shows she played after quarantine as intensely emotional, for the performers and the audience.

“Being a performer is about giving people an emotional space,” she says, “Because people are just tore up right now. There’s so much grief and anxiety, just in any crowd in America.”

Ben Arthur (@MyHeart on Twitter) is the creator and host of SongWriter. His latest song, “Persistent Ghosts,” is about traumatic memory.