“I don’t want to go on about it / But we’re back in business / Just a sweet, natural start / We will flower,” Florence Shaw declares on “Anna Calls from the Arctic,” the first song on Dry Cleaning’s sophomore album Stumpwork. She’s true to her word: The LP’s tone-setting opener heralds a subtler, stranger new era for the U.K. quartet, emboldened by the universal acclaim for their full-length debut New Long Leg. The band’s jangling guitar-rock grooves persist, but as the exception, rather than the rule—they are increasingly keen on marching down unexpected sonic avenues, complicating the instrumentation that underpins Shaw’s sometimes-spoken, sometimes-sung vocal mosaics. Stumpwork has enough in common with its predecessor so as not to throw fans for a loop, but is very much its own moody, nuanced animal, an expressive and expectation-defying showcase of Dry Cleaning’s blossoming sound.

After vocalist and lyricist Shaw, guitarist Tom Dowse, bassist Lewis Maynard and drummer Nick Buxton released their 2019 EPs Sweet Princess and Boundary Road Snacks and Drinks, catching the ear of London’s 4AD along the way, they teamed with producer John Parish (PJ Harvey, Aldous Harding) and engineer Joe Jones to record their first full-length at Rockfield Studios in rural Wales. Dry Cleaning were already keen on another go before New Long Leg’s April 2021 release, and reunited with Parish and Jones later that year, first by testing out their new material with a two-day rehearsal at Bristol’s Factory Studios, then by returning to Rockfield for twice as long. The band suffered a pair of personal losses during this time, mourning Maynard’s mother Susan—whose garage was where Dry Cleaning first played together, inspiring Boundary Road’s title—and Dowse’s grandfather, to whose memories the new album is dedicated.

Heartbreak, though, is just one color on Stumpwork’s emotional palette, neighboring anger and humor alike. The entire album is tinted with “the [severe] degradation we’ve witnessed in the past few years,” as Dowse notes in press materials, its instrumentals tending more towards space—emptiness by another name—and discord. Dry Cleaning already know themselves capable of ginning up grooves that gallop like mustangs; now, they opt for arrangements that wind and stutter, embracing a melange of influences, as if to better reflect the fragments of modern dystopia that Shaw expertly assembles into songs. As Dowse told Paste last year, “I’m not really interested in being a technical guitarist, I’m much more interested in how much I can communicate emotionally through a guitar.” He and Shaw are in constant conversation on Stumpwork, batting hope and despair around while Maynard and Buxton join them in kicking the pat “post-punk” descriptor often applied to the band to bits.

The tracks that followed New Long Leg the closest, two of which were released as singles, are easily identified. The sub-two-minute “Don’t Press Me” leads with a signature Dowse guitar groove, part sliding chords and part spidery riffing, the electric guitar backed by acoustic strums, as well as Maynard and Buxton’s sure-handed low end. “Don’t touch my gaming mouse, you rat,” Shaw orders, a defense of her chosen form of escapism that is effortlessly funny for its fierceness—softly singing the hooks, she pleads with her own brain, “You are always fighting me / You are always stressing me out,” while Dowse whistles along. “Gary Ashby,” named for a family tortoise who went missing in pandemic lockdown, is perhaps the most earnest song Dry Cleaning have ever written, pairing bright jangle- and dream-pop guitars with Shaw’s sweet crooning and unusually straightforward lyrics: “Have you seen Gary? / Family tortoise / Are you stuck on your back without me?” she frets. Dry Cleaning don’t linger long on these ideas (the album’s two shortest tracks), as if eager to move beyond the territory they already charted at length on New Long Leg.

They do just that on aforementioned opener “Anna Calls from the Arctic,” which sounds unlike any Dry Cleaning track, drawing inspiration from the work of film composer John Barry. Maynard’s bass is followed by Buxton’s odd, skittering percussion and tranquil synth tones, then Dowse’s spindly guitar riff. Shaw’s narrator sounds overwhelmed (“I see shit everywhere”), and the instrumental continues to shift around her, with Buxton moving from clarinet and tenor saxophone to vibraphone, then back again. Rather than becoming exasperated by her situation, Shaw sing-speaks as if completely at peace, finding transcendence in the everyday in one verse (“I like it when / You can see inside houses / From a car it’s cozy”), then mocking late capitalism’s punishments and empty pleasures in the next (“Nothing works / Everything’s expensive / And opaque and privatised / My shoe organising thing arrived / Thank God”). Dry Cleaning let the song linger in her eventual absence, with Dowse’s guitar sinking to the bottom of the ocean over Maynard and Buxton’s swaying groove.

“No Decent Shoes for Rain” is built around some of Dowse’s most emotional playing yet, his delicately distorted intro like a familiar face as seen through a downpour. Here, Dry Cleaning look grief in the eye and try to cope: Just short of two minutes in, the band drop out and leave only Dowse idly noodling on his guitar, as if the track is losing its will to continue, and soon after, Shaw sings, “My poor heart is breaking,” an admission made particularly affecting by its frankness. Even in mourning, Shaw finds herself musing on digital disconnection (“I’ve seen your arse but not your mouth / That’s normal now”) and consumer culture (“I’m bored but I get a kick out of buying things / Autonomy can be found at the shops”). Halfway through the song, she repeats, “Okay, well,” as if she’s trying to back out of a conversation that’s run its course. Just when you think the song is over, it doubles back, rebuilding its momentum with interlocking riffs as Shaw reminds us once more, “I’ve seen a guy cautioned by police for rollerblading.”

Those are just the singles—beyond them, Stumpwork continues to overflow with engrossing idiosyncrasy. Dry Cleaning build “Kwenchy Kups” on reedy acoustic guitar, snare rim taps and tambourine, with Shaw insisting, “Things are shit but they’re gonna be OK,” while looking ahead to a trip to “see the otters,” clinging to that simple joy. The intricacies of her vocal approach are on full display here: She emphatically sticks the last word of “A lot of faff,” her delivery dreamy, yet dripping with disdain—later, she conjures images of “Peaceful fish meat, lying dead and flat in a chiller / Pleated curtains partly hanging / Partly pushed against the tinted window so it looks like a giant butt / You can say I don’t give a fuck, dick face.” The juxtaposition of surprising, laugh-out-loud absurdity with humdrum domesticity is a time-honored Dry Cleaning tradition.

Against the woozy guitar and bass of “Driver’s Story,” Shaw murmurs, “Rough first part / Love second part / It’s cool stuff but we want different styles,” as if posting Google Doc comments on the music itself. Over the warped freak-funk groove of “Hot Penny Day,” between a heavily reverbed guitar riff in one headphone and distant sax skronk in the other, Shaw observes, “I guess I don’t ever ask for what I want / I see male violence everywhere,” then asks, “Are these exposed wires all good? / Near the steam?” as if returning to Maynard’s mother’s cramped garage where Dry Cleaning first formed, moving seamlessly between introspection and memory. And on the enthralling “Liberty Log,” she repeats, “It’s a weird premise for a show, but I like it,” exploring the phrase’s every wrinkle, as if reveling in the pleasures to be found simply by opening one’s mind to unexpected possibilities.

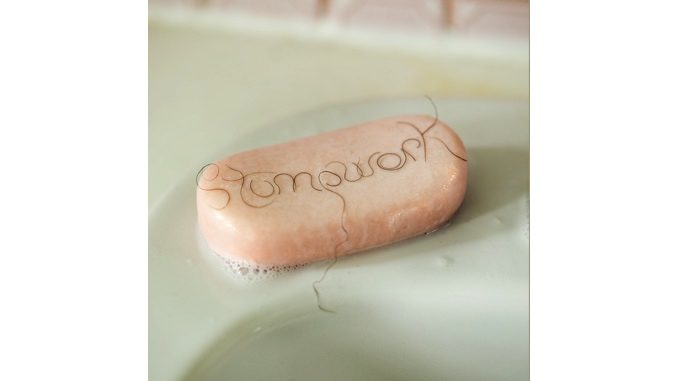

One of Stumpwork’s greatest strengths is its tension between curiosity and apathy, opposing forces that clash throughout the album. Often, it feels like oblivion is winning. Amid the dissonant sprawl of closer “Icebergs,” Shaw observes, “Sometimes it’s hard to find a silver lining,” pausing for what feels like forever before adding an almost hostile, “Eh?” The midtempo title track evokes complete disconnection: “I feel your approach / All the hairs on my arm raise up / because … you are wearing a fleece / that has become electrified,” Shaw says, the pause’s comic timing precise—and her, unfeeling, the punchline—while later, she surrenders, “I am not in charge of what I do / The only thing I could think to ask was / ‘Do you like stumpwork?’” That’s going to be a yes from me.

Scott Russell is Paste’s music editor and he’ll come up with something clever later. He’s on Twitter, if you’re into tweets: @pscottrussell.