The story of the modern bootleg can’t be told without mentioning Bob Dylan. Indeed, most count 1969’s Great White Wonder, an unofficial collection of unreleased Dylan recordings, as the first significant rock bootleg. Produced by the Trademark of Quality bootleg label, Great White Wonder included early home recordings, studio outtakes, and, most notably, tracks featuring Dylan and The Band from the sessions that would later yield 1975’s official Basement Tapes compilation. The frenzy over this previously unavailable material marked a change in how the public—and the record industry—viewed leftover or even discarded media. Suddenly, the stuff on cutting-room floors became more than clutter or mere curiosities. These previously neglected recordings, even if not yet thought of in terms of historical value, definitely posed commercial possibilities.

Dylan’s camp at Columbia Records didn’t take long to jump on this wagon. As early as 1971, Dylan’s second greatest hits volume—its inclusions handpicked by the artist himself—featured previously unreleased studio and live recordings. After the success of the aforementioned Basement Tapes, Columbia would wait a decade until it released another large batch of Dylan rarities into the wild. 1985’s sprawling Biograph box set spanned the first two decades of Dylan’s career and captured imaginations with 18 of its 53 tracks having been previously unreleased. These included rare live performances from legendary shows, outtakes from studio albums, and alternative versions of known songs. The compilation soon went platinum and laid the conceptual groundwork for 1991’s The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991. This inaugural volume, like Biograph before it, confirmed what Dylan fans had always suspected: Dylan had been holding out on us.

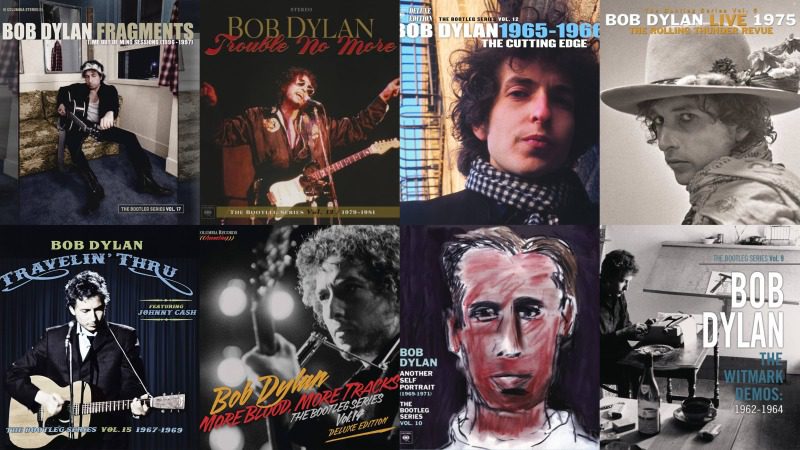

15 additional volumes and nearly 35 years later, that suspicion has proven true beyond our wildest dreams. Not only has the “vault” shown to be an endless trove of treasures, but The Bootleg Series itself has evolved into more of a curated collection of stories than a mere dumping ground for unreleased material. These stories have included transcendent live performances during transformative moments in Dylan’s growth as an artist; tour compendiums that find him shaking up history and flexing new creative muscles; and extensive studio recordings that help explain how the albums and songs that have marked our times came to be. For instance, Through the Open Window, the 18th installment just released this autumn, hitches a ride alongside a desperately young Dylan as his aspirations take him from smalltown Minnesota to the epicenter of the American folk revival in Greenwich Village and even the heart of the civil rights movement. It’s a beautifully documented journey and an example of what The Bootleg Series does at its very best moments—the type that appear on this list.

Of course, as is the case with any impossible task, there are some guidelines we’re following. Each volume of The Bootleg Series is represented here, but no volume gets tapped for more than two inclusions. Also, no songs are repeated. That just gets too reductive—not to mention boring really quickly—for an artist with Dylan’s remarkable breadth of work. Lastly, only tracks from the standard versions of these releases are being considered. That means no “Deluxe” or “Collector’s” editions. In the inclusive spirit of The Bootleg Series, everything found here can be readily streamed or purchased without taking out a second mortgage. If you do have a burning desire to go listen to 65 minutes straight of “Like a Rolling Stone” rehearsals and takes—and every Dylan fan should at least once—you can have at it on your own time and dime.

All of that said, never has there been a body of work quite like Bob Dylan’s, and it’s abundantly clear just how much painstaking care has gone into preserving and sharing all the beautiful, vulnerable, confusing, and even humorous moments that have come and gone during his legendary journey as an artist. Many of those moments are here, and we’re all the richer for that. Happy bootlegging!

*****

25. “Spanish Is the Loving Tongue” (Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (1969-1971))

It’s hard to imagine many fans clamoring for a deeper dive into the much-maligned Self Portrait era. And yet, one of the charms of The Bootleg Series has been its knack for revealing that even the weakest periods in Dylan’s career have redeeming qualities. Unreleased cuts like this take on “Spanish Is the Loving Tongue” might very well have changed perceptions of this ill-fated covers album. Hearing Dylan sit alone at the piano with Charles Badger Clark’s tale of cross-cultural love should be any defense’s Exhibit A in making the case that he wasn’t simply phoning these sessions in. Dylan tinkered with this song many times over the years, but this version cuts right to the corazon.

24. “He Was a Friend of Mine” (Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991)

Dylan’s gift for language has often overshadowed his power as a singer. This outtake from his self-titled debut—and the second overall track of The Bootleg Series—demonstrates that even a very young Dylan had the ability to interpret traditional material and imbue it with new depths of feeling. The simple words and melody of the tearful “He Was a Friend of Mine” require Dylan’s soft, plaintive vocal to carry the emotional heft and fill in the details of a lost companion. How he does so much with so little at such a young age boggles the mind. It’s a performance that still dampens the eyes all these years later.

23. “New Danville Girl” (Vol. 16: Springtime in New York 1980-1985)

So, did this girl hail from Danville or Brownsville? Good luck getting the facts straight from a guy who can’t remember anything about a movie except that it starred Gregory Peck. This outtake from the Empire Burlesque sessions gives us an earlier glimpse of the sprawling epic “Brownsville Girl,” arguably the only interesting song on 1986’s otherwise abysmal Knocked Out Loaded. Depending on who you ask, it’s either one of Dylan’s greatest songs or one of his most ridiculous swings and misses. Either of those options sounds pretty good at that point in the ‘80s for Dylan, and “New Danville Girl” might actually convert some naysayers with its simpler production and crisper vocals. Whether you prefer girls from Danville or Brownsville, these recordings find Dylan at his most ambitious, outrageous, and humorous as he takes us on a cinematic romp through the workings of a hazy memory.

22. “Girl from the North Country – Rehearsal” (Vol. 15: Travelin’ Thru, 1967-1969)

The Bootleg Series has never shied away from taking listeners behind the scenes. Not only do these moments give us a chance to see how some of our favorite songs came about, but we also catch glimpses of a private version of Bob Dylan that we would never see otherwise. One of the highlights of Travelin’ Thru finds Dylan sitting down with Johnny Cash and working through their famed Nashville Skyline duet, “Girl from the North Country.” To actually see the pair annotating the song as they figure it out has the simultaneous effect of making us feel like we are unworthy to be flies on this particular wall while also humanizing these musical titans. There’s something so utterly charming to hear Dylan sharing space with one of his friends and heroes. When Cash asks him to work on this particular number, Dylan bashfully replies, “Oh, I don’t know if I could, Johnny.” Apparently, it takes the Man in Black to reduce Dylan to once again being a teenager listening to records in his bedroom.

21. “Lay Down Your Weary Tune” (Vol. 18: Through the Open Window 1956-1963)

The most fascinating part of The Bootleg Series’ latest installment, Through the Open Window, comes from watching Dylan gradually begin to unlock whatever it is that makes him Bob Dylan. He uses traditional folk songs to find his footing and hone his chops and soon moves on to adopt their language and tropes to tell his own stories. On this poignant recording from his famed 1963 Carnegie Hall concert, Dylan fills the cavernous hall with images of nature’s own melody as he debuts the beautiful ballad “Lay Down Your Weary Tune,” a song he had recorded only a few days prior. The depth of this rendition speaks to both Dylan’s rapidly emerging command as a performer and the urgency he must have felt as songs were starting to come faster than he could possibly share them.

20. “Can’t Wait – Version 1” (Vol. 17: Fragments – Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997))

There’s no such thing as too much Time Out of Mind. That’s the only appropriate response to anyone of the opinion that an entire Bootleg Series volume dedicated to remixing this album and sharing its alternate takes, loose ends, and live performances seems like overkill. It’s also one of the rare instances where a discarded version actually trumps the take that landed on the album. If the “Can’t Wait” that made the final cut of Time Out of Mind hits like an agitated, alienated reminder that nobody pines quite like Bob Dylan, then “Version 1” on Fragments sounds utterly cracked and unhinged. This pulsing version with an alternate lyric sheet begins in a hush before Dylan, in all his gravel-throated glory, asks: “Ever feel just like your brain’s been bolted to the wall/ All the screws are tightened, and you’re cut off from it all?” It’s about this time that you realize that this is the sound of madness taking hold. And we’re disturbingly along for the ride.

19. “Farewell, Angelina” (Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991)

It’s never been uncommon for listeners to discover Dylan songs through other artists. Indeed, many of his most celebrated early songs were first popularized by contemporaries like The Byrds, Joan Baez, and folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary. However, even after Baez introduced this song to audiences in 1965, Dylan fans had to wait another 26 years until The Bootleg Series Vol. 2 first introduced them to the fare Angelina. Dylan only ever took one stab at recording this simple strummer in 1965 before abandoning it altogether. While we can debate in circles over just who “Angelina” is (Baez, Dylan’s folksinger days, or just the heady times?), we can definitely appreciate the song as a transitional moment that saw Dylan marrying the traditional melodies of his past with the surrealist images that would lead to his most popular work of the ‘60s.

.

18. “Dreamin’ of You” (Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased 1989-2006)

This list will continue to gush about what an inspired songwriting roll Dylan found himself on during the Time Out of Mind era. It’s a creative momentum that would lead to his resurgence as a recording artist and remind fans that Dylan could still write a song capable of striking a nerve all these years later. The obsessive “Dreamin’ of You,” a Time Out of Mind outtake and a single promoting Vol. 8 of The Bootleg Series, possesses that power to burrow beneath our skin. It’s also a frankenstein of sorts that speaks to Dylan’s process. We recognize producer Daniel Lanois’ murky production and rolling drums, but we might also notice that Dylan cribs lyrics from other songs that landed on the album, primarily “Standing in the Doorway.” Is this a first stab—stylistically miles apart—at that dimly lit, melancholy ballad, or is Dylan a mechanic with a pile of lyrical spare parts that he can use to tune up whatever engine he’s working on? It’s a fascinating glimpse under the hood in either case.

17. “John Brown” (Vol. 9: The Witmark Demos: 1962-1964)

Many listeners likely discovered “John Brown” through Dylan’s MTV Unplugged appearance. That’s because until he played a fiery, almost-spoken bluegrass version of it that night, the song had laid dormant for the better part of Dylan’s career. He had only ever recorded it for a 1962 Folkways Records compilation under the pseudonym “Blind Boy Grunt” and had just recently started playing it again in concerts after having shelved it for a quarter century. Depending on who you ask, the anti-war “John Brown”—maybe best described as Dylan’s Dulce et Decorum est—ranks either as his great, forgotten protest song or a disposable, cliched early stab at polemical songwriting. If you’re not sure which side of the barbed-wire fence you sit on, give Dylan’s early demo for M. Witmark & Sons publishing a listen. We think you’ll agree that there’s more of “Masters of War” here than hackneyed fist-shaking.

16. “Mr. Tambourine Man” (Vol. 5: Bob Dylan Live 1975: The Rolling Thunder Revue)

Many of Dylan’s signature tunes pop up throughout The Bootleg Series. That’s more than alright. Not only can you never get enough of songs like “Mr. Tambourine Man,” but listeners also get the chance to hear these tunes tag along with Dylan throughout the many permutations and stylistic shifts of his career. Of all the versions scattered across these volumes, this solo performance from The Rolling Thunder Revue might be the most moving. The nasal addresses of earlier versions have long since vanished, replaced here by a newfound urgency as it sounds like Dylan is pulling this “jingle, jangle” tale of “magic, swirling ships” from his throat and breathing it out through clenched teeth. It’s hushed and intimate while somehow also visceral. While most of the attention from this tour gets paid to the souped-up full-band numbers, this beautiful track reminds us of Dylan’s ability to mesmerize an audience all on his own.

15. “Slow Train” (Vol. 13: Trouble No More 1979-1981)

Not everyone followed Dylan into the desert during his Christian era. Ironically, some who anointed him a prophet a decade earlier took umbrage when he opened up about his own faith. While some listeners couldn’t stomach the content of the message (or how it was preached), it’s hard to deny the sincerity with which Dylan embarked on his mission. “[This song’s] called ‘Slow Train Coming,’” Dylan announces to a crowd at San Francisco’s Warfield Theatre. “It’s been coming a long time, and it’s picking up speed.” It might be corny and preachy, but there’s nothing dismissable about the performance. A zealous Dylan turns the stage into a pulpit, spitting out a warning that we better get our act together before that slow train pulls into the station. The R&B style and backing vocals he began tinkering with on Street-Legal come to full fruition here. Regardless of faith or religious packaging, it’s an absolute boogie as Dylan does what he’s always done: call out greed, corruption, and hypocrisy while pointing to the skies as a “hard rain” looms in the distance.

14. “Angelina” (Vol. 16: Springtime in New York 1980-1985)

If nothing else, this list has the market cornered on perplexing songs about Angelinas. So, that’s nice. Another running theme throughout The Bootleg Series finds Dylan leaving superior songs off relatively shitty albums. While some fans may go to bat for Shot of Love, the record sure could have used a tall glass of “Angelina,” originally slated to close out the album. It’s been called “impenetrable” by many, and I’m still not sure if it’s sheer brilliance or total cringe the way Dylan manages to rhyme “Angelina” with everything from “concertina” to “hyena” and “subpoena.” Still, there’s a remarkable quality to the song, a slew of nonsequitous religious and secular imagery that fascinates even if we’re not quite sure where it all leaves us in the end. As with a lot of Dylan’s best songs from this era, it’s best just to enjoy the dizzying, astonishing ride.

13. “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry – Take 8” (Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965-1966)

Alternate takes are usually shelved for a reason. Sometimes they don’t fit the tone or style of an album. More often, though, they just don’t work. They’re misfires that are curious to listen to or, at best, a missing link that informs how the greenlit take came about. On rare occasions, though, an alternate take not only works but also makes us totally rethink a song. This souped-up take on “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry” was among the first tracks attempted during the sessions for Highway 61 Revisited. It’s a bouncing, careening ride, more akin to the style of album-mate “From a Buick 6” than the ambling, bluesy version ultimately chosen for the record. Which train you choose to board on a given listen might just depend on where you’re heading and how fast you want to get there. And don’t be fooled into thinking the formula of simply adding velocity works all the time. A sped-up “Visions of Johanna” also appears on this volume, and it’s a bloody mess.

12. “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” (Vol. 6: Bob Dylan Live 1964, Concert at Philharmonic Hall)

Dylan’s “Halloween” show at Manhattan’s Philharmonic Hall seems to get short shrift when stacked against other volumes of The Bootleg Series. That may be in part because what’s witnessed here is far more subtle than being thrust into the heart of a social movement or betraying one’s tribe by going electric. Here we find Dylan in transition. He’s at the height of his powers as a “protest singer” (never his label of choice) but already looking ahead to a more surreal type of songwriting. Perhaps, having one foot out the door let Dylan loosen up on a night that turned out to be relatively lighthearted and extremely enjoyable. On “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” we hear Dylan chuckling before launching into a version that finds him singing to the hall’s rafters in a way that surprises the audience. They erupt with equal enthusiasm as Dylan stops the show with an intense and masterful harmonica breakdown before the final verse. It’s a beautiful, no-fucks performance that plays as a farewell of sorts given the advantage of knowing what comes next.

11. “Series of Dreams” (Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991)

If not for Oh Mercy, the last three decades probably look a lot different for Dylan as a recording artist. While Dylan wrote extensively in Chronicles: Volume One about the challenges of making the album—including an entire scrapped version and multiple songs he couldn’t quite wrangle—the most promising takeaway remains that he was once again writing great songs. Despite producer Daniel Lanois voting for this version of “Series of Dreams” (minus later remixing and overdubs) to lead off the record, Dylan instead filed the song under the category of “one that got away.” It’s a shame, too, as the driving, multi-rhythmic drumming perfectly nudges the listener through Dylan’s mysterious accounts of the dream state. Luckily, The Bootleg Series, in its infinite wisdom, remedied the omission just a couple years later.

10. “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie” (Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991)

Dylan would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016 for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” The announcement of the award definitely shook some windows and rattled some walls at the time. Some thought it an inspired choice while others couldn’t wrap their heads around the idea of a popular songwriter becoming a Nobel Laureate. However, if we look back to this reading of a poem from Dylan’s famed 1963 Town Hall concert, it comes as far less of a surprise that Dylan’s lyrics would one day warrant the attention of Stockholm. When asked to write 25 words on what Woody Guthrie meant to him, Dylan gushed forth about five pages. It’s a beautiful tribute to his first great influence and a breathtaking rush of language that begins with a “twisted head” and leaves us staring out at the Grand Canyon as daylight fades.

9. “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” (Vol. 5: Bob Dylan Live 1975: The Rolling Thunder Revue)

“A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” stands among Dylan’s first great poetic achievements as a songwriter. It’s no wonder Patti Smith performed it when she accepted the Nobel Prize on Dylan’s behalf in 2016. On just the strength of a strum and its observational lyrics, the song stirs the soul as it hypnotically builds to its final titular refrain. What a total gas then to stumble into Dylan’s famed Rolling Thunder Revue tour and hear a rollicking, full-band version with Dylan barking out the “blue-eyed son’s” encounters while his bandmates holler out the choruses behind him. This type of amped-up experiment has every chance of stripping a song like this of all its wonder and pathos, and yet it works masterfully. Dylan pools the forces on stage for strength and finally sounds like an actual prophet as he sirens out a warning from the pulpit. It’s the type of powerful performance painfully absent on 1976’s live album Hard Rain, which failed miserably at sampling this tour.

8. “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go – Take 5” (Vol. 14: More Blood, More Tracks)

By no means am I suggesting a single drop of Blood on the Tracks ever be changed. That record, even more than redefining the breakup album, ushered in a type of pained, confessional, and vulnerable songwriting that needs to exist as long as humans continue to suck air and bleed. That said, we sometimes forget just how close that perfect album—in many ways “a creature void of form”—came to sounding completely different. Dylan bounced back and forth between a backing band and a more-stripped-down acoustic sound, and, as The Bootleg Series demonstrates, struggled to settle on versions of most tracks. Even if not a good fit for the album as finally realized by Dylan, he definitely conjured up a different type of magic on this alternative take of “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go.” Instead of being driven by Dylan’s harmonica and rapid phrasing, this stretched-out version slows the pace to a crawl, allows Dylan to take in the scenery, and gradually lets the backing build behind him. It’s a likely standout on a version of Blood on the Tracks that never came to be.

7. “I Shall Be Released – Take 1” (Vol. 11: The Basement Tapes Complete)

The legacies of Dylan and The Band will forever be entwined. However, by the time they gathered at the house lovingly dubbed “Big Pink” in West Saugerties, NY, they were headed in very different directions. Dylan, fresh off his infamous motorcycle accident, had begun to step out of the spotlight and return to his musical roots while The Band were on the cusp of bringing their Americana sound to the mainstream. The Basement Tapes have stirred the imagination since first leaked and bootlegged, and one of many fascinating aspects of these recordings is the chance to hear Dylan and the fellas piece together several tracks that would soon end up on The Band’s groundbreaking debut, Music from Big Pink. “I Shall Be Released,” not included on the original Basement Tapes compilation, may sound strange with Dylan sharing space with Richard Manuel’s falsetto and piano, but when the rest join the choruses, we get a beautiful glimpse of this Canadian powerhouse’s game-changing future.

6. “Red River Shore – Version 1” (Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased 1989-2006)

Dylan has talked about no longer being able to write songs like he did back in the ‘60s. In retrospect, he believes those songs were as much plucked out of the ether as written by himself. Still, something else must’ve been in the air in the late ‘90s as Dylan put together the tracks for Time Out of Mind. It’s not hard to understand how this stab at “Red River Shore” might not have fit the tone and texture of that record; however, it’s impossible to fathom how a song this achingly beautiful and mysterious sat on the shelf for over a decade. Like Johanna before her, the girl from the Red River Shore has a conquering hold on the protagonist’s mind. Dylan settles into a lovely, gravelly storytelling voice in this tale of time, love, and regret, our narrator so absorbed in the memories of a girl that we start to suspect that she’s as much an idea he’s faithfully clung to as a real person at this point. It’s the type of song that keeps us coming back time and time again, hoping for a happy ending or resolution that we know will never come.

5. “Visions of Johanna” (Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The “Royal Albert Hall” Concert)

Each night on Dylan’s 1966 World Tour played out as a tale of two sets. Dylan would play the first set on his own with just acoustic guitar and harmonica. The second set featured Dylan and his backing band The Hawks (later known as The Band) plugged in and prepared to piss off any stuffed-shirt purists in attendance. Suffice it to say, the chaos of those electric sets—and Dylan’s battles with disapproving audiences—tends to garner more attention than the solo acoustic portion of the evenings. Recordings like the mistakenly titled “Royal Albert Hall” concert (actually from the tour’s Free Trade Hall show in Manchester) reveal what a shame it would be to neglect Dylan’s opening numbers. As the tour progressed, “Visions of Johanna,” off Dylan’s soon-to-be-released Blonde on Blonde, became a regular inclusion. Dylan wastes nary a breath on this delicate, pin-drop performance as he juxtaposes the ideals in his mind with the banality of reality. It may be remembered as the quiet before an electrical storm, but it’s also as beautiful a performance as Dylan ever gifted us.

4. “Blowin’ in the Wind” (Vol. 9: The Witmark Demos: 1962-1964)

Demos tend not to be very exciting. By their very nature, they’re a rough draft, not fully baked, inchoate, and just beginning to scratch the surface of whatever they’re destined to become if anything. Still, all great works spring from somewhere, and sometimes that demo might even blossom into a song that changes the course of history. That was certainly the case for “Blowin’ in the Wind,” Dylan’s first composition submitted to music publishers M. Witmark & Sons. To listen to Dylan alone on guitar as he lays this song down for presumably the first time can be a profoundly moving experience. The power of its truth already emanates from its verses and perplexing refrain, and we have the humbling advantage of knowing just what impact this song will make in the years to come. It’s all the more perfect that Dylan lets out a cough between verses. It reminds us that truth and beauty often arise from the most unassuming beginnings.

3. “Maggie’s Farm” (Vol. 7: No Direction Home: The Soundtrack)

Legend has it that Dylan had not intended to “go electric” at 1965’s Newport Folk Festival. After all, acoustic renditions of songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” in years prior had made him a favorite son of the event. However, as one account goes, after hearing festival organizer Alan Lomax put down The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Dylan assembled a band overnight and prepared to take them into the proverbial lion’s den the following evening. “Maggie’s Farm” was the first shot fired in a short, three-song electric set. It’s no doubt the loudest thing to ever hit Newport at the time, and the reaction to the jarring, amplified performance depends on who you ask. There were definitely boos, but opinions differ on whether they were aimed at Dylan for bringing his blasphemous voltage to such hallowed grounds, at organizers for the poor sound quality, or again at Dylan for not playing longer. In all likelihood, the negative reactions were a mix of all of the above, and Dylan even smoothed things over by returning to the stage for a couple acoustic numbers. It would be 37 years before Dylan performed again at Newport (wearing a wig and fake beard no less), proving there is a direction home … eventually.

2. “Blind Willie McTell” (Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991)

Many longtime fans consider “Blind Willie McTell” to be the holy grail of Dylan’s rarities and unreleased songs. Tucked away near the end of Vol. 3, this Infidels outtake became the smoking gun that proved Dylan’s powers as a songwriter had not diminished even as his studio output slumped. It’s a simple enough song, featuring Dylan on piano and Dire Straits’ Mark Knopfler—a too-often-neglected collaborator of Dylan’s—on acoustic guitar. This stark, haunting tune rolls in like a thin fog as Dylan guides us through bleak American imagery of displacement, slavery, and rampant “power and greed.” It’s far from the first time that Dylan has turned a damning eye to the unraveling fabric of the world around us, but it had been years since a song had carried such impact. In the years following its release, “Blind Willie McTell” became a staple of Dylan’s live show, some versions returning the song to its jazz melody roots.

1. “Like a Rolling Stone” (Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The “Royal Albert Hall” Concert)

Give credit where credit is due. This recording captures arguably the greatest heckle in rock and roll history. As Dylan and The Hawks batten down the hatches to close out the night, someone in the audience calls out, “Judas!” But it’s not this slanderous allusion to biblical betrayal that pushes this moment to the top of our list. It’s Dylan’s response. “I don’t believe you,” he sneers back. “You’re a liar.” Then Dylan turns to his bandmates and instructs them to “Play it fucking loud!” as they launch into a glorious, defiant, and deafening salvo of “Like a Rolling Stone.” It’s absolutely beautiful, cacophonic mayhem as Dylan lobs his voice like grenades over the noise blaring throughout the hall. If Newport had been a notice that Dylan would most likely go his own way, then “Royal Albert Hall” was a middle finger to all the folknik pearl clutchers who couldn’t dig it. In honor of this historic moment, we encourage you to play this track fucking loud!

Tip: If you are streaming this track, listen to the version closing out Vol. 7: No Direction Home: The Soundtrack. The track on Vol. 4 criminally cuts out Dylan’s “Judas” interaction on most streaming platforms.