A great folk album will let you play the eager eavesdropper calling on the other line, palm over the receiver. It’ll make you surrender fully to that urge to listen in, to peer through a cracked door and hear a balladeer crooning quietly under yellow lamplight. Ideally, it will take you back to the time where music could only be transmitted on a person-to-person basis, where you’d be lucky to catch a new song and hold onto it with memory alone. Experiencing folk music was, and always will be, something ephemeral.

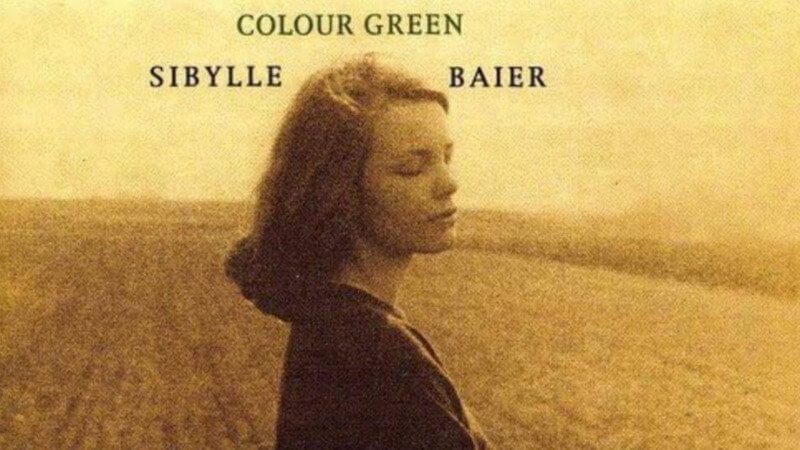

The question of whether to expose the intimacy of music lost to time was presented to Robby Baier 20 years ago, when he compiled a mix of his mother’s original songs that she’d made in Germany in her twenties. Between 1970 and 1973, Sibylle Baier taped the music that became the Colour Green album on a reel-to-reel with just a nylon-string guitar and her voice. It wasn’t until 2006 that the songs ever saw the light of day, when Robby made a CD of the songs to give to some of their family members for Sibylle’s 60th birthday. Robby also gave a copy to Dinosaur Jr. ‘s J Mascis, who gave the mix to a label, Orange Twin Records. Orange Twin distributed it that same year and, in the span of a few months, Sibylle’s audience grew bigger than just a handful of loved ones. Now, her monthly listener count is well into the thousands.

Sibylle recorded her songs without knowing that, one day, they’d amass a cult following, and that’s what makes Colour Green as intimate as it is—she plays for an audience of one. Each performance is up close and personal: Baier’s voice is warm and assured, an anchor to the lithely fingerpicked guitar accompanying her. She sounds as if she might be humming from right over your shoulder, her sense of nearness owed to the detail of the physical recording process. This is only bolstered by the intimacy of her confessions, which she reveals with a swift, uncomplicated pen. She interweaves the expository necessities of narrative with peaks of longing, even when describing something as ordinary as returning home from work in the album’s opener, “Tonight.” She writes about a man who awaits her at home, who sits in an easy chair and butters his toast before asking, “What’s that sorrow you bear?” Sibylle cuts the song’s ordinariness with a dull pull of grief.

Growing up in Germany, Baier felt a near-religious devotion to the countryside, which saw her through the trials of youth and any lasting growing pains. Colour Green houses a dizzy contrast between city and farmland, where Baier can’t fantasize of a larger, grander life without her loyalty to her home spilling out of her. All of these sentiments culminate in “I Lost Something in the Hills,” an ode to the environment of her adolescence, where tall grass and sloping valleys serve as a catalyst for waves of bittersweet nostalgia. Baier declares, “Oh, I yearn for the roots of the woods, that origin of all my strong and strange moods,” considering her environment and personal development to be inextricably linked. The lyric makes the record for me—Baier’s assertion that the cause for all of her feelings can be tied to the earth, to the physical space that made her. Her metaphors are playfully mixed: “I grew up in declivities,” she sings, “others grow up in cities.” That “something” she lost in those hills is so carefully made illusive and unnameable—any further specification would only reduce that breadth of feeling to a cliché.

The title track brings Baier to this place of urban ennui, where she imagines herself as a girl in New York City “wearing a sweater color green.” Baier’s New York is one of flashing seasons and strained memory, and she leaves all out of sorts: “The city has changed me, I’m no longer the same.” Naming the album Colour Green suggests a commitment to remaining this girl in the sweater, but as the album’s mythology deepens, it becomes clear that Baier doesn’t exist in any one place—her city life is mostly fancied and her country days have come and gone. Baier doesn’t definitively exist in any one place or phase, coming to rest only in the domestic spaces where her music lived for so long. Baier’s craft sports a dreamy sheen regardless of setting, illuminating even the smallest moments with her indelible touch.

The album’s bare atmosphere allows for Baier to experiment more subtly, utilizing silence and spaciousness. Nowhere does she do it better than on “Forget About,” a delicate ballad about worn-in love. Baier unveils the concept of a kind of joint mind, where her trust in her partner allows her worries to subside, “You made me forget about have, want, exert, and all of a sudden, I feel proud.” Her words here floor me always—they’re so simple yet so tender, an entirely honest account of the selflessness of a pure, unproblematic love. In writing about memory, Baier renders herself speechless, starting lyrics she never finishes. She sings, “you made me forget about,” and never completes the line, as if whatever comes next has already been forgotten. Baier expresses love with both omission and stark repetition, the latter of which spins through “Softly” and its “my daughter, my son” refrain. Baier describes her experience with motherhood in questions and dialogue as time flashes by: “Off and away, they set out for living. Love them if they ever come, wherever they’ve gone.” It is no wonder Baier’s son felt so eager to share her music; it’s a display of affection that was never intended to be heard, making it all the more sensitive.

In the 20 years since Robby opened the door to his mother’s mastery, Sibylle Baier has been propped up in folk history as a truly important voice. Like Connie Converse she was unsung—unknown—at the time she wrote her songs but celebrated for them many years later. While Colour Green remains her only album, it stands alone in representing Baier’s singular talent: her knack for blending the personal and universal and creating something entirely new out of it. She manages to capture the desires of a generation of young women by simply writing about her own experience. All good folk artists sunder the formalities of songwriting until they’re splayed out, reduced to their nascent states, and Baier is no exception: she builds her songs from small riffs and simple melodies, creating from fundamentals an interminable, ineffable “something.”