Today (June 5) is the latest in a string of Bandcamp fundraisers where the company is waiving all their revenue shares on digital and physical sales for 24 hours to benefit artists and labels. The music platform also recently announced that they would donate all their revenue shares every Juneteenth (June 19), starting this year, to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. With both of these promotions running in quick succession and with the blatant racism that’s been put on display in America for the past few weeks, now is the perfect time to purchase art from Black creators. The Paste staff compiled a list of some of our recent favorite albums by Black artists, all of which are available to purchase on Bandcamp, and we highly recommend buying them today or on June 19.

Kaia Kater: Grenades

Earlier this week, I published a short list of Black roots artists whose music grapples with or at the very least touches on racial injustice and oppression, and while it was only meant to be a sampler, there are so many more artists I could’ve included. One of those is Kaia Kater, an artist who was featured prominently last year on our list of the best folk artists to watch in 2019 after her 2018 album Grenades had a powerful effect on me (and so many others) upon release. However, I admittedly had forgotten about it until a kind Twitter user mentioned her name (Thank you!) in a thread about other Black roots artists to know. Grenades was powerful in 2018, but, let me tell y’all, it is so important to listen to again today. I’ve been revisiting the album this morning, and Kater’s graceful balance of addressing both her Canadian and her Grenadian heritages hooked me back in immediately. Spoken-word interludes (like “Power! Power! Power!”) tell stories of oppressed people of color, and her smooth, powerful folk-pop delivery forces you to listen. On closer “Poets Be Buried,” she shares a piece of passed-down for surviving a world that doesn’t always care whether or not you do, and never backing down in the face of hatred: “I had a daughter and I taught her all I knew. / Fight in the gutter and love the work you do. / How for to warn her of hatred hiding in the blue … I asked my father if this is all there is. / A home that won’t claim you, a country that rescinds. / You are your own saint, a center to hold, a life to live.” —Ellen Johnson

Purchase here

Thundercat: It Is What It Is

While the cat noises and fart sounds on his last album, 2017’s Drunk, offended one prominent music critic so much he nearly crashed his car in a fit of frustration, Bassist Stephen Bruner (aka Thundercat) didn’t actually need to tame his prodigious appetite for variety. On previous Thundercat albums, he revelled in his own zaniness, but he also showed a knack for going right to the edge of incoherence while maintaining just enough of a consistent thread. Listening to a player with a range that rivals the late bass giant Jaco Pastorius—and, arguably, the chops to match—part of the appeal comes from just watching the ideas roam free. That makes it all the more remarkable that Bruner has decided to rein in his wanderlust on his fourth solo LP, It Is What It Is. It’s not that It Is What It Is lacks variety. Much like on his other output, Bruner once again draws freely from the wells of funk, soul, disco, jazz, rock, hip-hop and lo-fi experimentation. The crucial difference this time is that he shoehorns those influences into a startlingly smooth flow that somehow accommodates dazzling technical proficiency. On It Is What It Is, Bruner brings ’70s-style R&B balladeering (“Overseas,” “How I Feel”) and fusion (“Interstellar Love,” “How Sway”) to the forefront as other styles recede into supportive roles. In terms of the impact of the record as a complete listening experience, the payoff is tremendous. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

Purchase here

Irreversible Entanglements: Who Sent You?

Irreversible Entanglements’ music is as dense as the band’s name: Thick bass grooves underpin errant saxophone swells, as crashing cymbals accentuate the negative spaces between political verses of spoken word poetry. The melodies and time signatures don’t always feel pegged together, but the group inevitably finds their groove in the chaos. Their music is overwhelming, but Irreversible Entanglements’ excellent second album, Who Sent You?, proves that it’s essential, too. The Philadelphia-via-New York-via-Washington D.C. free jazz quintet met at a Musicians Against Police Brutality concert in 2015 following the murder of Akai Gurley by an NYPD officer. The musicians immediately linked up and booked the studio time that yielded their 2017 self-titled debut, an album marked by its radical leftist politics and swirling free jazz. Camae Ayewa—who also performs as Moor Mother—grounds the group with her poetry, a combination of free-associative desperations and elegant aphorisms: “A mountain ain’t nothing but a tomb for fire,” she forcefully says on album opener “The Code Noir / Anima”. —Harry Todd

Purchase here

Yves Tumor: Heaven to a Tortured Mind

Yves Tumor’s new album opens with Sean Bowie shouting “I think I can solve it / I can be your all.” Later, on “Medicine Burn,” they claim “I can’t lift my own troubles,” then shout a reversal on single “Kerosene!”: “I can be anything / tell me what you need.” Heaven to a Tortured Mind is emphatically about what Tumor can and can’t do, because what else are pop anthems about? “Creep” is about how Radiohead is incapable of fitting in with mainstream society, while “I Will Always Love You” is a declaration of Whitney Houston’s enduring love amid crisis. Yves Tumor have long skirted the line between pop candor and experimental psychedelia, often landing somewhere far away from both in a wonderland of threatening, dagger-sharp guitar riffs and gossamer vocal production. In many ways, 2018’s Safe in the Hands of Love was Tumor’s official rockstar moment. Listening to Heaven for a Tortured Mind will make you question your own memories of the singer, because they’ve never sounded more immediate, more relatable or more desirously messy. —Austin Jones

Purchase here

Tre Burt: Caught It From The Rye

On first listen, Tré Burt’s debut album Caught It From the Rye feels a bit like Bob Dylan cosplay. All the markers are there: the coarse, slightly nasal voice, the rustic fingerpicked guitar, the just-out-of-time duet and even the harmonica. It’s easy to cast this release aside as just another folk record in a long line of folk records that sound virtually exactly like this, but that doesn’t credit what makes this album special: Caught It From the Rye takes a tried-and-true formula and injects it with a triple shot of Black joy and heartbreak. Burt’s stories, be them freewheeling tales about watching time pass by or hyper-focused political screeds, represent a breath of fresh air in the Americana genre. And it’s his Dylan-esque protest songs where he shines the brightest. “And Mother Nature, I guess she caters / To those with white skin / I don’t feel well anymore / To darkness I’m returnin’,” Burt croons on “Undead God of War,” the sort of track that could have hit home with African American listeners had the song been released in the mid-’60s alongside The Times They Are a-Changin’. But by using traditional folk methods to write about issues facing the Black community around the peak of Black Lives Matter in the aftermath of Trump’s electoral victory (the record, which originally came out in late 2018, is being re-released a year-and-a-half later by John Prine’s Oh Boy Records), Caught It From the Rye is radical and a must-listen. —Steven Edelstone

Purchase here

Moses Sumney: græ

It’s a special thing to watch a promising artist rise to meet the moment in front of them. Some never quite get there. They retreat from the pressure or they run into a ceiling that’s lower than expected. Sometimes bad timing or unlucky circumstances prove insurmountable. And then there’s folks like Moses Sumney, the prodigiously talented and artistically ambitious American singer-songwriter who has relentlessly resisted the shortest path to stardom over the past several years. With a stunning voice, a striking figure and a lot of famous friends on his side, he could’ve at any point submitted himself to the hit machine and made a straightforward pop/R&B record that likely would’ve fast-tracked Sumney to household-name status. Instead, he has taken an omnivorous approach to his music, absorbing folk, soul, jazz, ambient and classical music into his unique sound. Still, his debut full-length—2017’s Aromanticism, an intimate exploration of lovelessness—sparked a fire that even Sumney couldn’t sidestep. Anticipation for a follow-up has run high in recent months, stoked by a series of gorgeous singles and an unconventional roll-out: Sumney released part one of his sophomore album, græ, in February, and part two arrived this month. Now that all 20 songs are out, it’s clear Moses Sumney has taken one giant step forward from Aromanticism, and in doing so has bounded off the precipice of expectation into a dazzling unknown. Clocking in at just over an hour long, the album is a vast landscape of words and sounds that stretch far across the artistic spectrum, but at the same time feel very much like members of the same extended family. Each shares a certain amount of DNA, but their inherent individualism is what gives Sumney his increasingly singular style. —Ben Salmon

Purchase here

Algiers: There Is No Year

As on 2015’s self-titled debut and its 2017 follow-up, The Underside of Power, Atlanta band Algiers’ latest effort, There Is No Year, is meant to inspire a revolutionary energy, both politically and musically, in the listener. Initially written as an epic poem, lyricist and multi-instrumentalist Franklin James Fisher croons and chants in murky gothic metaphors. There are repeated references to “the sound,” an ominous and threatening representation of revolution that Fisher seems to have lost faith in: “Everything starts to fade / Under the weight of silence,” he sings on “Nothing Bloomed.” The album also pulls from Christian visions of the apocalypse, be it through the invocation of the four horsemen (“There Is No Year”) or a crisis of faith that portends the failure of the revolution (“Wait for the Sound”). —Harry Todd

Purchase here

Ric Wilson / Terrace Martin: They Call Me Disco

Following 2017’s Negrow Disco and 2018’s BANBA, Chicago funk/disco rapper Ric Wilson has shared a collaborative EP with jazz musician and hip-hop producer Terrace Martin (Kendrick Lamar, Snoop Dogg). The pair began work on the EP last year, which continued into 2020. The EP also features appearances from Corbin Dallas, BJ The Chicago Kid, Malaya and Kiela Adira. They Call Me Disco is smooth, fun-loving and charismatic, blending retro funk-pop, playful hip-hop, exuberant disco and even psych-tinged R&B. “The disco-inspired funk never stops,” says Wilson. “Me and Terrace wanted to make something people can move to and free themselves.” Martin adds, “This record is a beautiful reminder the disco never stops. Keep smiling, keep dancing, and keep loving.” —Lizzie Manno

Purchase here

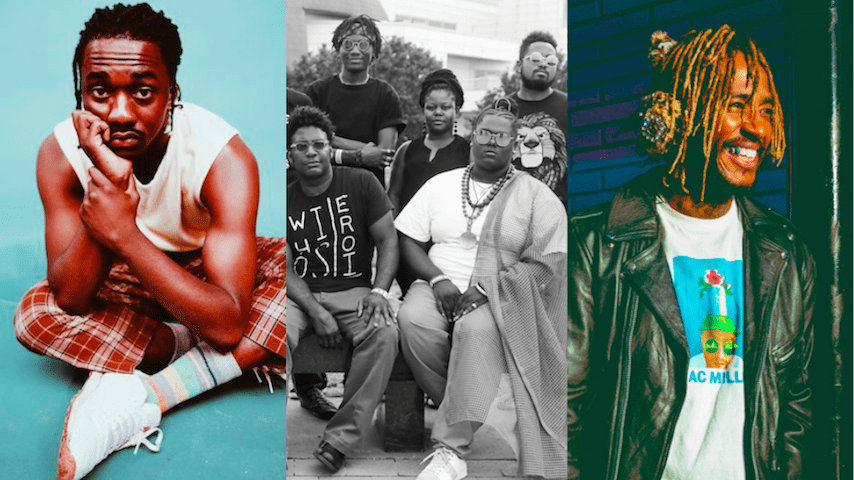

Mourning [A] BLKstar: The Cycle

Cleveland collective Mourning [A] BLKstar describe themselves as “a multi-generational, gender and genre non-conforming amalgam of Black Culture dedicated to servicing the stories and songs of the apocalyptic diaspora.” That rich culture is plentiful on their fifth album and double LP The Cycle, out now via Don Giovanni Records. Their brass-led neo-soul and hip-hop is stirring and rebellious—there’s a reverence for Black musical traditions as well as a burning desire to keep building new ones. The Cycle is far from monolithic—they fold in inventive, electronic beats with raw bluesy speak-sing and soulful crooning, and they’re happy to shapeshift and subvert expectations along the way. The album rests on themes of self-love, solidarity and perseverance—three things we could all use right now. —Lizzie Manno

Purchase here

Sault: 5 and 7

These days, it’s hard to remain an anonymous musician, but no one seems to know who or how many people make up Sault. What we do know is that they released two albums last year—5 and 7—on the Forever Living Originals label, and critics can’t get enough of them. Both albums shared the number two slot on Bandcamp’s 100 best albums of 2019, and for good reason—their groovy, free-flowing arrangements are almost too good to be true. Simultaneously sounding like lost funk classics and modern mash-ups of bass-heavy soul, pop and post-punk, these records possess a rare exuberance. —Lizzie Manno

Purchase here

Clipping.: There Existed an Addiction to Blood

Far from fiction, Clipping.’s latest album, There Existed an Addiction to Blood, turns the framework of horror on its head. Fear runs rampant across each track, but instead of channeling nightmares through imagination, the L.A. experimental hip-hop trio show us the terrifying nature of our own kind. There Existed an Addiction to Blood is the deranged culmination of everything Clipping. have been experimenting with—but not quite nailing down—over their previous two albums. Here, they’ve given their most focused project, all while exploring the darkest corners of humanity over envelope-pushing industrial production. With a carefully constructed chaos, Clipping. throw us into their torturous musical realm and boldly ask us to find the art in fear. —Hayden Goodridge

Purchase here

Kyshona Armstrong: Listen

After we published a list of Black roots artists whose work touches on racial injustice and oppression earlier this week, I put out a call on Twitter for others to leave their recommendations. One of those recs came from Adia Victoria, the Nashville-based blues singer who we included on that very list. She suggested fellow Nashvillian and soul/blues/roots powerhouse Kyshona Armstrong, whose 2020 album Listen is available to purchase on Bandcamp. It’s a seriously powerful (not to mention groovy) LP that Armstrong dedicates to ” every silent scream, every heavy load, fearful thought and simmering sense of anger that you have tried to hide from the world. I see you. I hear you.” Those are all phrases we keep hearing this week—”I see you. I hear you. I stand with you. I’m listening.”—and while what we hear and see may not always be expected or comfortable, that’s what makes the message important and productive. Armstrong maps out decades of oppression against Black Americans (and their role in building this country) in “We The People” (“We turned and toiled / left our blood-soaked in the soil / they left our bodies to burn,” she sings in her fortified alto. “Treated our nation/ like the cells of their plantations / but what did We earn?”) There’s something so powerful about Armstrong declaring what might otherwise sound like a simple statement: “We belong.” These songs span country and rock ‘n’ roll, gospel and the blues, love songs and lullabies, prayers and protest anthems. But the most powerful among them may be the closer, “More In Common,” a plea for compromise and understanding and, as this album’s title may suggest, to just listen. “We got more in common / Than what tears us apart,” she sings. Songs like this give me hope. —Ellen Johnson

Purchase here

Vagabon: Vagabon

Halfway through Vagabon’s 2017 debut Infinite Worlds, Lætitia Tamko stepped away from her guitar. The song, “Mal a Laise,” was an exercise in atmosphere, with droning synth loops layered over reverb-heavy vocals murmured in both French and English. It stood at odds with the guitar-centric indie rock production that defined the rest of the record: It was a detour, but it almost felt like a homecoming. Maybe it was. Tamko’s sophomore effort, the self-titled, self-produced Vagabon, is a more formless affair, a cosmic journey through synthetic sounds, lush orchestral suites and lyrical self-realization. The result is an ambitious album overflowing with generosity and empathy, warm in production and rich in theme, even if it largely lacks the punch that made Infinite Worlds so immediately memorable. But homes are made to shelter aspirations, dreams, fears, anxieties, hopes, doubts. Homes are sanctuaries, and that’s what Tamko has created with Vagabon. —Harry Todd

Purchase here