The greatest albums and singles don’t drop from the sky to your doorstep; there’s no sharp-beaked songbird carrying them in swaddling clothes from an other-worldly paradise. They’re crafted in the polyphonic pantheons of the music industry—unique recording studios that inform a record’s sound and feel, not just with their top-of-the-line gear but with their mood-inducing settings. And these sounds you’ve been so addicted to all these years aren’t only the product of the amazing artists and musicians you know so well, but also of talented engineers and producers—who labor over the sonic slices of invention, helping bring to life a songwriter’s once intangible vision. So here they are, 10 classic sessions in country, soul and rock ’n’ roll.

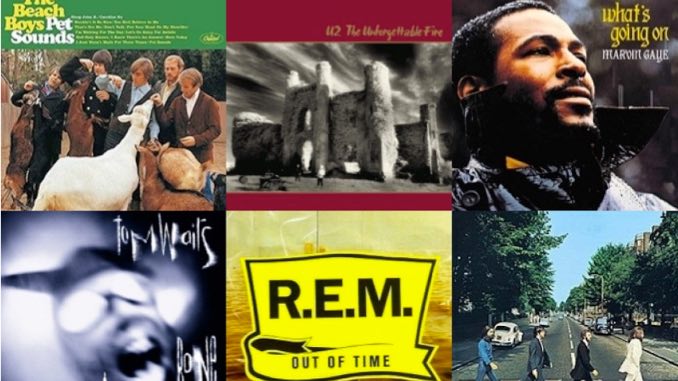

1. Western Studios, Hollywood / 1966 / The Beach Boys • Pet Sounds

The nondescript building at 6000 Sunset Blvd. that was once Western Studios has hosted its share of legends over the decades, but it will forever be known as the place where Brian Wilson created his masterpiece, Pet Sounds. When visitors to the facility—which was renamed Cello after being purchased by its present owner in 1999—ask to see the room where Wilson worked his musical alchemy, they’re invariably startled by the modest size of Studio 3, which measures just 15 feet wide and 32 feet long. How did all those musicians (21 of them on one session) and their gear fit into such a tight space? And how did Wilson get such big sounds out of such a miniature environment?

According to Mark Linett, Wilson’s studio collaborator, the diminutive size of Western 3 contributed to the perception of bigness. “In those days,” Linett explains, “you didn’t cut a huge-sounding record in a huge room. Because you were cutting everybody live, you wanted to be able to open up any mic and have whatever came through it be pleasing, whereas in a big live room, the bleed would be detrimental to the sound. And 3 just worked well that way. The other thing is, it was an age when players knew how to play together, to interact without headphones or baffles, with everything isolated — y’know, modern recording.” Also contributing to the impression of aural spaciousness was Wilson’s extensive use of Western’s brick-lined echo chambers (which are sill in use).

By the beginning of 1966, when he began recording Pet Sounds, the 23-year-old budding auteur was regularly coming up with elaborate instrumental arrangements he conceived on the fly and shaped into sophisticated, almost orchestral pieces in the space of three or four hours with the aid of a crew of world-class session musicians anchored by drummer Hal Blaine—the same players Phil Spector used to create his “Wall of Sound.” Under Wilson’s leadership, the unit was able to consistently generate what bassist Carole Kaye calls “room spirit.”

“All we heard of the melody was Brian sitting down at the piano, playing it and singing it once or twice to give us the feel,” Kaye remembers. “The rest of the time he spent in the booth. After Chuck Britz set up the board, Brian did it all. He’d give out directions for some rhythmic styles maybe to the guitars, to Hal, and maybe he’d change the bass parts, back and forth like that, as we’d run down the tune. After quite a while we’d do a take. Later on, when I heard the vocals, I thought Brian was a genius for being able to put all that together.”

The Pet Sounds vibe is still present in the old building, according to Matthew Sweet, who recorded his 2000 album In Reverse in the adjacent Studio 2. “Cello is probably my favorite professional recording studio ever,” he says. “One day during In Reverse, Brian came over from 3 and visited us, and we nervously played him our track in progress. At the end he jumped up and yelled, ‘I love it! I f—-ing love it!’ Needless to say, we were psyched. I remember thinking to myself, ‘Thanks, Cello!’”

Cello’s owner put it up for sale last year and all those approached passed, including Paul Allen, Rick Rubin, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Tom Petty. But at presstime we learned office manager Candace Stewart and tech head Gary Myerberg had found an investor, enabling them to buy and run the operation themselves. If the deal goes through, their first order of business will be to change the name of the studio back to Western. —Bud Scoppa

2. Slane Castle, County Meath, Ireland / 1984 / U2 • The Unforgettable Fire

It was as likely a place as any to start a sonic revolution. In 1690, William of Orange defeated James II at the Battle of the Boyne, near the present-day site of Slane Castle in County Meath. It was a crucial moment in Irish history. William’s victory confirmed Protestant supremacy in Ireland and gave rise to the sectarian violence that continues to this day. It was probably no accident, then, that U2 decamped in May, 1984 to Slane Castle, 30 miles outside Dublin, to record its fourth studio album The Unforgettable Fire. But the four young Irish men who lamented the violence of Sunday, Bloody Sunday were not about to choose sectarian sides. They had a much higher revolutionary purpose in mind. They wanted to change the world in the name of love, and they wanted to change the world through rock ’n’ roll.

Produced by Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois—the team that would go on to mastermind U2’s classic albums The Joshua Tree and Achtung, Baby—The Unforgettable Fire is a departure in nearly every way from what has come before. Inspired by their airy surroundings and the openness of the ancient recording studio, the straightforward rock of the first three U2 albums is here replaced by the patented Eno/Lanois ambient wash, and in songs such as the title track and “Bad” the band achieves an ethereal majesty, still rooted in the world of rock ’n’ roll, but soaring off to previously unexplored heights.

Bono said in 1987, “The Unforgettable Fire was a beautifully out-of-focus record, blurred like an impressionist painting … People thought we were the future of rock ’n’ roll and they went, “what are you doin’ with this doggone hippie Eno album?” But we owe Eno and Lanois so much for seeing through to the heart of U2.”

That heart, always profoundly Irish and profoundly universal, found its truest expression inside the walls of Slane Castle.—Andy Whitman

3. SugarHill Studios, Houston, Texas / 1948 / Lightnin’ Hopkins • “T Model Blues”

Isolated from New York, Los Angeles and Nashville, the independently owned SugarHill Studios has been a virtual open mic for the sounds swirling through the honky tonks and juke joints that dot the Gulf Coast. With a history stretching from George Jones and Bob Wills to Sir Douglas Quintet and Destiny’s Child, the studio has launched dozens of national acts. Former owner Huey P. Meaux’s SugarHill recordings codified what has become known as “swamp rock,” and his 1970’s Freddy Fender recordings sent Top 40 country in startling directions.

But before Meaux there was founder Bill Quinn who, despite racial attitudes in the post-WWII years, opened his studio to all comers. In a short period in 1946-47, Quinn recorded classic country sides (“Drivin’ Nails in My Coffin”) and the only Cajun tune ever to make the Billboard Top 5, Harry Choates’ “Jole Blon,” a.k.a. the Cajun national anthem. But Quinn’s most important session involved little known bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins. For $75, Hopkins cut “Short Haired Woman” in his first session for Quinn’s Gold Star label and it became a regional hit. Hopkins followed up with two tracks that made the Billboard Top 10 R & B charts. “T-Model Blues” (1948) and “Tim Moore’s Farm” (1949) established Hopkins and boosted the emerging Texas blues scene.

Current studio co-owner Andy Bradley is currently writing a history of the studio and has had to rely on old books and interview material for information on the Hopkins sessions. “I interviewed Calvin Owens, who played some sessions with Lightnin’, but he can’t recall dates or players. At this point in time, it’s all second-hand. It’s such a shame no one realized the historical significance.” Despite the fact little is known of the sessions, Quinn undoubtedly sewed the seed that spawned the recording explosion of the 1950s, the golden years of Houston blues.—William Michael Smith

4. Prairie Sun Recording, Cotati, Calif. / 1992 / Tom Waits • Bone Machine

Tom Waits wanted a different recording experience for his 1992 album, Bone Machine. But even Waits admits he got far more than he bargained for. Inside a non-soundproofed barn at Prairie Sun Recording Studios in the wine country north of San Francisco—clanging away on car fenders for percussion and laying down tracks using classic analog equipment—Waits delivered a no-frills masterpiece that’s grisly, macabre mood and tone was perfectly captured by the primitive technology on hand.

“I was so disturbed; the studio we got was totally wrong,” Waits explained to KCRW’s Chris Douridas a year after the recording, still a little pained by the memory. “I was stomping around thinking, nothing will ever grow in this room.”

What grew was arguably the defining album of Waits’ stellar career, a haunting and haunted rumination on decay, relational disintegration and the ever-grinning skeletal presence of the Grim Reaper. The, umm, bare bones production fit the music, which features a sonic landscape critic Django Boren memorably described as “the sound of a German dwarf beating on farm machinery and shouting through a bullhorn.” Under-produced and non-commercial have never sounded so demanding, or so bracing and startling in their immediacy.

“It worked out okay,” Waits conceded during the KCRW interview. “Fortunately, we stumbled upon a storage room that sounded so good. Plus it already had maps on the wall. So I said, ‘That’s it, we’re sold.’” —Andy Whitman

5. John Keane Studios, Athens, Ga. / 1990 / R.E.M. • Out of Time

It’s strange to think so many incredible albums have been recorded in this little white, wood-panel house—brick front porch, bench swing, wind chimes and all—in this quiet residential neighborhood in Athens, Ga. But over the last 20 years, luminaries like R.E.M., Billy Bragg, Cowboy Junkies, Uncle Tupelo, Drivin ‘N’ Cryin, Bloodkin, Indigo Girls, Taj Mahal, Robert Earl keen, and Vic Chesnutt have each left a little mojo behind after seeing their visions realized here. You can feel it radiating from the soundproofed walls.

Inside John Keane Studios, the founder/head honcho himself is hard-at-work mixing Widespread panic’s latest live album. As Keane slides his swivel chair across the worn hardwood floor of the control room, a familiar voice floats down the hallway—Bill Mallonee is upstairs in Studio B, laying down acoustic guitar and vocal tracks for his new double-disc. His former outfit, Vigilantes of Love, cut both Killing Floor and Blister Soul here.

Keane says a big part of why people want to record at his studio is that the environment is more relaxed and conducive to creativity. “Commercial studios are more like in industrial parks, more like doctor’s offices,” he says.

And perhaps another draw for Keane’s studio is R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck, who’s produced many an artist here. One time, about 12 years back, he brought along his friends Jeff Tweedy and Jay Farrar to cut a little acoustic record called March 16-20, 1992. “It was an amazing group of musicians,” Keane says of the Uncle Tupelo sessions. “They had those songs down, to the point where they only had to play ’em once or twice. Most of the songs were just them all sitting around in a circle, doing it live.”

But perhaps the most important sessions Keane was ever a party to, were for R.E.M.’s landmark album, Out of Time. “One of the most amazing moments I’ve had here,” Keane says, glancing through the open door into the multi-colored Christmas-light glow of Studio A, “was when Michael Stipe cut the vocals for ‘Losing My Religion.’ It was one of those moments where everything comes together. Chills ran up my spine when I heard it. I just knew it was going to be an amazing song, and that it would be a lot of people’s favorite.”

The band went on to spend six weeks at Keane’s studio, sweetening the album’s soundscape by adding complex harmonies, diverse instrumentation and the work of unmistakable guest musicians like The B-52’s’ Kate Pierson and rapper KRS-1.

Reminded of his impressive résumé since the studio opened in 1981, Keane says that—no matter the band—there’s a common sound to many of the records he’s worked on. “Part of it is because people use a lot of the instruments I keep here—a couple Martin D-28 [acoustic] guitars, a Hammond organ, my own drum kit, a 12-string and all sorts of telecasters … If you listen to an Indigo Girls or Bill Mallonee or R.E.M. record, it’s the same guitar, the same Martin D-28 with the same microphone on it.” —Steve LaBate

6. Sound Emporium, Nashville, Tenn. / 1999 / Various Artists • Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?

It’s a mystical studio, and there are a hundred stories about strange—but wonderful—things happening during sessions. The enchantment of Sound Emporium is attributed, in part, to the studio’s builder, “Cowboy” Jack Clement, legendary engineer, songwriter and producer, who, some say, had the Midas touch. Clement played on sessions, and engineered and produced records for Jerry Lee Lewis (it was Clement who recorded “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On”), John Hartford, Iris Dement and Johnny Cash, to name just a few. Clement opened the studio in 1969 and built a perfect echo chamber without any acoustical engineering blueprints.

In the spring of 1999, another legendary producer birthed a project at Sound Emporium that indelibly changed the way bluegrass and traditional American music was perceived. Engaged by the Coen Brothers to provide music for their film, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, T Bone Burnett knew Sound Emporium was, as he puts it, “the best sounding room I’ve ever been in to record acoustic music.” One of the largest tracking rooms in Nashville, Studio A has a blacked ceiling that gives the illusion of being under a night sky. Structural elements, like hundred-year-old barn wood and “silo-looking things” clinch the details. And with Burnett’s homey touches, Studio A was turned into his very own back porch.

So was there anything magical happening during the recording of O Brother?

“Yeah,” answers Burnett. “Everything. Everything was like that.”

Whether it was the vibe of the room, the considerable skills of Burnett and engineer Mike Piersante, or even the spirit of Cowboy Jack, the O Brother soundtrack sold six million copies in under two years without any mainstream-radio airplay, converted or reintroduced a gazillion music lovers to traditional music, and (perhaps most delightfully) delivered a sharp-toed kick to country music’s groin, which had repressed acoustic music for years. —Charlene Blevins

7. Abbey Road Studios, London / 1969 / The Beatles • Abbey Road

Probably the most famous set of recording studios in the world, and a prime London tourist attraction in its own right, Abbey Road is now 73 years old. Best known as the place where The Beatles and Sir George Martin created some of the finest pop music ever, it was actually transformed from a private residence to its current state thanks to the vision of Captain Osmund ‘Ozzy’ Williams, who decided North West London needed a classical studio. Aptly, the first session at the new HMV Studio (as it was known then), saw Sir Edward Elgar conduct the London Symphony Orchestra performing his own “Land Of Hope And Glory,” but it also hosted everything from the likes of Glenn Miller’s final recordings to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon and, more recently, Oasis.

During the1960s, Abbey Road’s Studio 2 became synonymous with The Beatles. “It was where they first started,” says Geoff Emerick, the band’s legendary engineer. “It was like home to them.” Emerick started at Abbey Road when he was just 16-years-old and says the technical training he received was second to none. It was there he worked with producer Martin as a recording and mixing engineer on The Beatles’ final session and, arguably, finest album, Abbey Road (1969). “George and I had a really good working relationship,” says Emerick, who’s now writing an autobiography about his years with The Beatles. “And because we’d worked together so often, towards the end we didn’t used to say a lot in sessions because we could read each other’s minds.”

Originally slated to be called Everest after the cigarette brand Emerick favored, Abbey Road was eventually named after the leafy street on which the ‘EMI Studio’ is still situated. The record is Martin’s favorite by The Beatles and, during the sessions, he utilized the studio’s brand-new 8-track recording capabilities to capture the band’s increasingly complex compositions, including side two’s epic medley. The result: a musical masterpiece that will forever be a benchmark in pop and rock ’n’ roll. Said Martin in documentary The Abbey Road Story, “If you believe, as I do, that a house has atmosphere capable of absorbing the personalities and emotions of its inhabitants, you will have no difficulty in appreciating the unique quality of Abbey Road.” —Helen M. Jerome

8. Castle Studios, Nashville, Tenn. / 1948 / Hank Williams • “Lovesick Blues”

If only because it was the first recording studio in what would become Music City, USA, Castle Studios influenced music history as fundamentally as any other studio in the world. The brain child of three WSM Radio engineers who recorded the Grand Ole Opry broadcasts and the era’s first syndicated radio specials, and who watched in dismay as all the country artists scurried off to New York or Chicago to record, Castle Studios was a child borne of necessity. Or opportunity. First begun in WSM studios after broadcast hours, the original studio didn’t have space for the large lathe used to cut the vinyl. Instead, they sent the signal, via a dedicated phone line, to a room 12 miles away. They’d have to make a phone call to see if it was a good take. After moving to a separate room in the nearby Tulane Hotel, the early Castle Studios gave birth to nearly half the hits on country radio—and several on the pop charts—between 1947 and 1955.

In addition to playing a pivotal role in Nashville becoming a music center, Castle was the exclusive home to one of the 20th century’s seminal artists. He was a young, unknown singer/songwriter from Montgomery, Ala., when he recorded his first demos there on Dec. 11, 1946. In early 1947 he recorded a little tune called “Honky Tonkin’,” which won him a record deal with MGM Records. It was Hank Williams, of course. A little bit superstitious, Williams danced with the one that brung him and, though his success up to then afforded him his choice of studios, on December 22, 1948, he went into the no-frills, converted dining room that was Castle Studio, and recorded an old Tin Pan Alley tune called “Lovesick Blues.” It became a 16-week number one, crossing over to the pop Top 25, and winning him an invitation to the Grand Ole Opry—and superstardom—cementing both Williams’ and Castle’s place in recording history. —Charlene Blevins

Motown Studios, Detroit / 1971 / Marvin Gaye • What’s Going On

During its golden era (1959-1971), Motown’s recording studio produced not only a jaw-dropping string of hits (nearly 70 percent of released singles entered the charts—357 in all) but the producers and musicians in the basement of 2648 West Grand—otherwise known as Studio A—created a new style, fusing elements of gospel, R&B, country and jazz into what is now known simply as “Motown.” The Supremes, The Temptations, Martha and the Vandellas, The Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, The Jackson 5, Marvin Gaye and Mary Wells are among the best known, but there were dozens of hit makers in the ’60s-era Motown stable.

While it’s common to talk about the “Motown Sound,” in reality there were as many “sounds” emerging from Hitsville, USA, as there were producers. And chief engineer Mike McClean and his crew made sure all of them made it to tape. McClean took Studio A from a cobbled-together, 2-track facility in 1959 to the cutting edge of recording technology and kept it there until Motown founder and president Berry Gordy moved the center of operations from Detroit to L.A. in 1972. Whether it was Holland-Dozier-Holland’s delicious, reverb-drenched productions or the funky psychedelia of Norman Whitfield’s work with The Temptations, McClean and his crew gave Motown’s recordings a live, bass-heavy sound that could make an AM car radio sound like front-row seats at The Apollo.

The recent recognition of Studio A’s house band, The Funk Brothers—in the movie Standing in the Shadows of Motown—highlights one of the essential elements that fueled Motown’s vitality over such a long period: the chemistry of a great rhythm section. Just listen to drummer Pistol Allen’s propulsive two-handed shuffle on Martha and The Vandellas’ “Heat Wave,” or the immortal James Jamerson’s squab bass lines on The Supreme’s “You Keep Me Hanging On.” And of course there’s Robert White’s indelible opening guitar line to “My Girl.” Bass player and Funk Brother Bob Babbitt says the group could quickly hear when a particular player was hot. “They could tell when a certain member was really into a song and they had ways of working around him,” he says. “The other guys would really key off a great performance.”

And some of the most inspired performances heard in Studio A would occur during the recording of the greatest Motown record of all, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. “The arrangements for the music told the musicians that there was definitely some groundbreaking going on,” recalls Babbitt. “The music itself dictated where the sound was going.” From David Van Depitte’s lush, soaring string arrangements to the boundary-shattering subject matter of social injustice, environmental consciousness and a direct, deeply felt faith in God, What’s Going On set a standard for R&B records that’s still unmatched. Three decades after it’s release, it continues to influence artists across the pop spectrum, and is widely regarded as one of the finest albums ever made.

Studio A was unique in that it was only ever used for Motown recordings—its history inextricable from Berry Gordy’s original vision and ultimate triumph on the charts. And while, for many, Motown represents the advent of factory-style commercial music making, the performances in Studio A and the passion brought to the songs recorded there gave them character and soul—they were calculated, to be sure, but they were never cynical. “The main thing is, Motown made people feel good,” says Babbitt. “I think that’s their legacy.” —Dave Sims

St. Catherine’s Court, Bath, England / 1996 / Radiohead • OK Computer

Was there a ghost in the machine when Radiohead recorded its breakthrough album, OK Computer, in 1996? Working on the follow up to its critically acclaimed sophomore effort, The Bends, the Oxford group started recording in a converted apple-storage shed for a month, tracking “No Surprises,” “Subterranean Homesick Alien,” “The Tourist” and “Electioneering.” Then Thom Yorke and co. decided they needed the inspiration of a new setting. So they upped sticks and moved themselves and their equipment further west to Bath, deep in the lush, green heart of the English countryside, and into actress Jane Seymour’s 15th Century mansion, St. Catherine’s Court.

“Studios are generally very horrible places for recording,” guitarist/keyboardist Jonny Greenwood told The Irish Times in 1997. “They’re pretty unmusical, so we just decided to turn a big empty house into a studio … [Jane] said to us, ‘come and stay,’ handed us the keys and told us to feed the cat.”

For two months, Radiohead took advantage of the unique home of the English star of Dr. Quinn: Medicine Woman and Live and Let Die. Seymour fell in love with the house instantly when she made the film Jamaica Inn there in 1982, and she purchased the property by the end of the first day of filming. Having spent years restoring it to its former glory, Seymour decided to allow others to use it when she wasn’t around. Recently, New Order and Robbie Williams recorded at the house, and The Cure has stayed there several times. But it’s the modern masterpiece, OK Computer, that seems most informed by the vibrations of the one-time monastery in which King Henry VIII kept his illegitimate daughter, having paid his tailor to raise her. (Incidentally, historical scholars might recall that Henry VIII’s third wife was also named Jane Seymour!)

Estate manager Grant Fanjul says the place’s appeal lies in being self-contained, with everyone living, working and eating together. In fact, Fanjul is usually the one preparing the musicians’ hearty meals and calling them to chow down in the kitchen at 1:00 and 8:00 p.m. every day. He also believes they appreciate being in the middle of nowhere, away from motorways or neighbors and enveloped in absolute quiet. “When we actually stopped playing music there was just this pure silence,” Yorke told Spin in 1998. “Open the window—nothing. A completely unnatural silence. Not even birds singing.”

Recording takes place anywhere in the house, which has nine bedrooms, six bathrooms and two kitchens, but the size and acoustics of the ballroom usually make it the main ‘studio.’ “We set up in the ballroom and the control room was set up in the library, which had these amazing views over the gardens,” bassist Colin Greenwood told Fender Europe. “There were some magical evenings as we sat down with pieces of music with the windows open.”

Yorke even recorded the haunting vocals for “Exit Music (For A Film)” in the stone entrance hall of St. Catherine’s Court, but he said that something in the house started to work against them after a while, rewinding and turning tape machines on and off. He’s convinced the house is haunted, and Grant Fanjul confirms there are three known ghosts at St Catherine’s Court—although he’s never seen them. A mysterious lady in blue caused one of the gardeners to leave the property the day he saw her, never to return. Another alleged ghost is that of an informer who could not forgive himself for revealing the whereabouts of local monks, who were then murdered. And according to Fanjul, there’s also a ghost dog that barks and brushes up against you as it passes by. So that’s where OK Computer gets its creepy vibe … —Helen M. Jerome