The cover of Asleep at the Wheel’s 1973 debut album. From left: Lucky Oceans, Leroy Preston, Ray Benson, Chris O’Connell, Floyd Domino and Gene Dobkin.

Asleep at the Wheel, the eight-time Grammy-winning, country-swing band, have been celebrating their 50th anniversary a year late, thanks to the pandemic. Their current tour, which features a mix of band members past and current, would be swinging through Cumberland, Maryland, in late October, and that seemed like a good opportunity to revisit the backwoods home in nearby West Virginia where it all began in 1970.

If only they could remember where the house was.

That’s how if I find myself following two vans carrying five band members and assorted friends down the backroads of Great Cacapon, West Virginia. The leaves, turning a gorgeous gold and scarlet, are a dangerous distraction, for the ridge-top roads are only one-and-a-half lanes wide and the slopes just off the blacktop are precipitous. After many miles of this, the vans turn onto an even narrower gravel road, but after a few more miles, they pull off to the side.

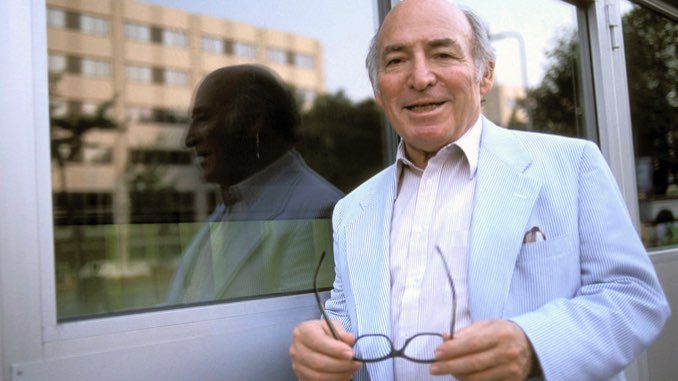

Ray Benson

Ray Benson, the only musician in every version of Asleep at the Wheel over its five decades, unfolds his six-foot, seven-inch frame and steps from the silver van to survey the landscape. His gray beard extends the length of his sternum below the brim of his black-mesh baseball cap and between the lapels of his gray-corduroy blazer. It has been 49 years since he last lived in this neighborhood, but he visited 10 years ago and surely he should remember his way. “All the trees that I remember,” he mutters, “are no longer here, and all the trees that are here, I don’t remember.”

Standing nearby are Leroy Preston, Chris O’Connell and Danny Levin, who all lived in the Magnolia House with Benson in 1970-71. Their memories are even dimmer than Benson’s. But those four musicians, along with Lucky Oceans (now stuck in Australia behind pandemic regulations), were college-age kids when they honed their musical chops and their musical identity at the ramshackle house hidden somewhere in these woods.

Asleep at the Wheel back in Paw Paw, West Virginia. From left: Leroy Preston, Chris O’Connell, Ray Benson and Danny Levin.

Those skills and that identity carried them into Billboard’s top-10 country chart, onto the Grammy stage, and into studios with collaborators such as Willie Nelson, George Strait and Emmylou Harris. If they could only find the building, they might reconnect with their beginnings. After all, like comic-book superheroes, every band has its own origin story. And this one started in the suburbs of Philadelphia where Ray Seifert and Reuben Gosfield were childhood pals long before they adopted the stage names of Ray Benson and Lucky Oceans.

“I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know Reuben,” Benson now says. “We were both obsessed with music and kept forming bands together. We’d go down to the pawn shops on South Street and buy blues records. We’d see Johnny Cash on TV and hear Motown on the radio. My cousin gave me an old wire recorder with a live recording of Big Bill Broonzy.”

“Ray and I went to a Gene Autry concert as kids,” Gosfield adds over a Zoom call from Australia’s West Coast, “and Gene rode out onstage on his horse. You don’t forget stuff like that. Ray and I went to see John Coltrane at that famous concert at Temple University. To be in Coltrane’s presence, a man so dedicated to music, was awe-inspiring. Ray shook his hand and said, ‘Mr. Coltrane, I enjoyed your concert very much.’”

It was this breadth of enthusiasms that made Asleep at the Wheel such an unusual band. They could make you laugh at a country novelty song or cry over a honky-tonk ballad, but they could also swing like a jazz band and stomp like a rock band. They were trying to figure out how to put all these pieces together when they discovered Bob Wills & The Texas Playboys, the great pre-World War II big band that personified Western swing. To this strong sense of history, Asleep at the Wheel brought an irreverent, ’60s energy. Gosfield would often leap up after a virtuoso steel solo and do his patented “crazy fool” dance.

Ray’s older sister Sandy was a student at Northeastern in Boston, and her boyfriend was Leroy Preston’s roommate. Benson and Gosfield jumped on Sandy’s invitation to come visit, and they spent hours jamming with Preston, who grew up on a Vermont farm listening to hardcore country music. Something clicked in Benson’s mind. He was tired of cities and wanted to join the era’s back-to-the-country movement. If they were going to do that, it would make sense to form a country band that the locals might want to hear.

Leroy Preston in his old bedroom at the Magnolia House

“I’d been in a rock band that played frat parties,” Preston remembers, “but I decided that was going nowhere fast. So I sold my drum kit, bought a guitar and listened to Hank Williams’ Greatest Hits and Robert Johnson’s King of the Delta Blues Singers non-stop. That got me writing songs. Ray had heard Commander Cody at Antioch College in Ohio, and he had the idea that we could do that kind of country-rock without the rock. That appealed to me, because this wasn’t just an excuse to get together and play. There was a concept for the band.”

Preston’s thick hair and thin mustache are now snowy, and he wears black-frame glasses. He doesn’t even pretend to know where the house might be. Our three-vehicle caravan goes down one side road and then another. At one point, we walk down a pathway past a “No Trespassing” sign. A red, wet stripe runs down the middle of the green grass. Darrell Arnica, an early roadie for the band who still lives in the area, points out a hunter’s blind nearby and says, “Someone dragged a deer carcass out of here not long ago.”

In the spring of 1970, Preston and Benson had driven down to Columbia, Maryland, where Gosfield was attending a different Antioch campus. A friend in Columbia said his parents owned an apple orchard in Paw Paw, West Virginia, and the musicians could camp out in the log cabin there. This was just what they were looking for: a rent-free place to work on their musicianship and absorb the rural way of life. Benson told his childhood friend, who was already a skillful bottleneck blues guitarist, that he would play pedal steel guitar in the new band. He would also share drumming duties with Preston, while Benson played guitar.

There was one problem: Gosfield’s friend had not told his parents about the arrangement. When the father showed up and found these hippies living in his cabin, he gave them a month to vacate the premises. They found a place by the railroad tracks in Levels, West Virginia, but that proved even less hospitable.

“Ray’s older brother Mike Seifert shows up,” Gosfield recounts, “and we decide to borrow some chairs in an old barn. Up comes this pick-up truck with old man Scanlon in it and he has a pistol out. Mike and I end up in jail and are released only on the condition that we get out of Hampshire County and never come back.”

But it was in Levels that the band got its first big break. The Hog Farm, the legendary California commune led by Wavy Gravy (aka Hugh Romney), was driving through West Virginia when they stopped for gas. The gas station attendant told them about a hippie band living down by the tracks. The Hog Farm school bus showed up at Asleep at the Wheel’s front door and everyone quickly bonded. Before long, the nascent band was invited to open for Alice Cooper, Hot Tuna and Stoneground at a Hog Farm outdoor concert in Washington, D.C.

“All of a sudden we had a name in Washington,” Benson says. “Before long, we were invited to open for Poco at Georgetown University. Jim Messina was so nice to us; he even mixed our sound. A week later, I drove back to Georgetown to hear the New Riders of the Purple Sage. Because I’d just played there, they let me backstage, and I got to hang out with Jerry Garcia. I explained what we were doing in West Virginia, and he said, ‘Oh, you’re woodshedding.’ I had never heard that term before, but it was exactly what we were doing.”

By “woodshedding,” Garcia meant the choice by some musicians to get away from all distractions for a time and work intensely on their musicianship. By this time, Asleep at the Wheel was in their third and longest lasting West Virginia home: the Magnolia House that we were now searching for.

Benson’s son and road manager, Sam Seifert, had a copy of the map that Gosfield had drawn in 1970 and sent to his parents so they could come visit the Magnolia House. His parents had deciphered its ambiguous instructions, but his bandmates were mystified by them now. Was the driveway before the rusted-out van on Campbell Lane or after it?

Wandering down the road was Chris O’Connell, the band’s original female lead singer, now wearing white hair and a gray “Full House Cycles” T-shirt. Back in 1970, she and her best friend Emily Paxton had been rehearsing country harmony singing in Arlington, Virginia. They figured it would be easier to join a band than to start one, so they were looking for the right opportunity.

“We went to see Poco at Georgetown,” O’Connell says, “but after the opening set by Asleep at the Wheel, Poco had lost all appeal. The Wheel was doing these classic country songs like ‘Wings of a Dove’ and ‘Wreck on the Highway,’ but they were young like us. We made some phone calls and got their address. We asked a cop in Berkeley Springs how to get to Great Cacapon, and he said, ‘You don’t want to go there; weird things happen up there.’ It was night by the time we arrived, but we found the driveway and the house with the lights burning. We just showed up and said we were singers.”

Floyd Domino and Chris O’Connell at the Magnolia House

“We had always had this idea of forming a country music revue with three singers and multiple instrumentalists,” Benson says, “so when Chris and Emily showed up, it fit into our plan. We had them sing the ‘oohs’ on Johnny Cash’s ‘Don’t Take Your Guns to Town’ and Willie Nelson’s ‘Hello Walls.’ They started doing gigs with us and suddenly we could do Loretta Lynn songs as well as Merle Haggard songs. We could only take one girl singer to California, and it was obvious that Chris was the one.”

The band was already doing a weekly gig at the local Sportsman’s Club, a membership-only venue for hunters and their wives. The audience at first eyed these out-of-state hippies with skepticism; this was only a year after the Manson murders, after all. But when the locals heard how well the band could play those old country songs, they adopted them as “our hippies.” The dancers would tell the musicians what songs they needed to play at the next gig, and that was one more part of the ongoing education.

“The way we sounded at the Sportsman’s was the sound of the Grand Ole Opry coming through a car radio in a 1961 Cadillac parked on the highest elevation of our property in West Virginia,” Gosfield says. “You needed a bright, forceful sound to get across through that car radio, and that served us well. It’s not the sound of Vanguard or Elektra Records, from an L.A. or a New York studio. It’s coming from Nashville with a lot of steel and a lot of echo. It’s a sound that we found really works.”

A whoop goes up, and Benson leads a charge up on overgrown driveway hidden around a curve in the gravel road. A quarter mile into the woods, there it is: the Magnolia House, the holy grail that our search has been pursuing. It’s not much to look at: a two-story ramshackle building, its walls covered in red roofing shingles, a quarter of them now missing. The porch is barely propped up by stacks of bricks, and the refrigerator smells like a science experiment gone wrong.

The Magnolia House

The current owners have given us permission to visit, and it’s clear that no one lives here on a regular basis. But one bedroom is habitable, and the stove is still hooked up; someone has been using the house as a base camp for hunting. But the musicians are ecstatic to have found it. Even Floyd Domino, the pianist who joined the band later in California before moving on to play for Waylon Jennings and Merle Haggard, is happy. “I never lived here,” he says, “but I’ve been hearing stories about it for 50 years.”

Preston is upstairs in the bedroom he once shared with Gosfield. Benson is in the front yard pointing out the location of the chicken coop he converted into a private bedroom—at least for the warm months. The house has always had electricity and a wood stove, but not indoor plumbing, and Levin points out the location of the outhouse and the spring. Domino wakes up Gosfield at two in the morning in Australia and gives him a FaceTime tour of the house.

Asleep at the Wheel at the Magnolia House: From left: Ray Benson, Floyd Domino, Leroy Preston, Danny Levin and Chris O’Connell with Lucky Oceans on the phone in Domino’s hand.

Everyone agrees that Asleep at the Wheel would never have been the band it became if not for the year and a half in West Virginia. They also agree they could never have become that band if they had stayed in the state. They had to move on, so they accepted Commander Cody’s invitation to move at the end of 1971 to Berkeley, California, and Willie Nelson’s invitation to move in 1974 to Austin, Texas, where the band has been based ever since.

“We did it the right way,” Benson argues. “We got to experience country music from the bottom of the honky-tonk world. We paid our dues and learned the business. It was quite the schooling. We’d go to get some lumber cut to repair the house, and the lumber guy says he plays guitar, so you sit up on a mountain playing fiddle tunes with him. You can’t get that experience any other way. You play the Sportsman’s Club, and you have to learn all these old country songs the crowd wants to hear.”

“West Virginia was a place where we could live in a band house together and not need a job,” Gosfield explains. “We could just practice and experiment all the time to create music that would appeal to both the locals and audiences in D.C. And living there gave us some legitimacy as a country band. and it soaked into us, absolutely. It was different, especially if you came from the suburbs of Philadelphia. You play a role and eventually it becomes real. We loved it; we started thinking of ourselves as hillbillies.”

Asleep at the Wheel performs at the Ali Ghan Shrine in Cumberland, Maryland.

After our visit to the Magnolia House, the band drives back across the Potomac River to clean up at the hotel and get ready for the early-evening gig at the Ali Ghan Shrine in Cumberland. The stage is inside a green, sheet-metal shed in a field owned by the Shriners and filled with camp chairs. Most of the audience is as old as Benson; some of them were fans when the band actually lived nearby.

To celebrate the anniversary, Asleep at the Wheel have released a new studio album, Half a Hundred Years, with 19 tracks featuring 44 past and present members of the band (just a small fraction of the entire alumni association). The songs include both new originals by Benson, Preston, Gosfield, O’Connell and Domino, as well as concert staples given a new twist with such guests as Willie Nelson, George Strait, Emmylou Harris and Lee Ann Womack. Songs from both categories fill the evening’s set list.

The show begins with the septet that was Asleep at the Wheel before the pandemic. But after 11 songs by that lineup, Benson invites Preston, O’Connell and Domino to take the stage. This expanded lineup leaps into “Take Me Back to Tulsa,” an old Bob Wills tune that the Wheel released as their first-ever single in 1973—and which is reprised with Nelson on the new album. With Katie Shore and Danny Levin taking twin-fiddle breaks, Cindy Cashdollar playing a hot solo on the pedal steel, followed by Domino doing the same on the piano, it’s like old times again. Benson’s lead vocal rides the syncopation like a surfer.

Preston sings both of the songs he wrote for Rosanne Cash: “My Baby Thinks I’m a Train” and “I Wonder.” Domino cuts loose on the piano as O’Connell sings “Bump Bounce Boogie.” She and Benson sing the duet on “The Letter Johnny Walker Read,” the band’s only top-10 single. Benson closes out the night by applying his still-strong baritone to a medley of “Route 66” and “Happy Trails to You.” It’s as if they were back at the Sportsman’s Club.

“I tell young people that all your experiences shape the music you play,” Benson says later. “Yes, I milked a cow; yes, we farmed. We lived off the land, but we quickly discovered that we couldn’t do that and be a band too. It all fed the music we played. When we got to California and told everyone we had just come from West Virginia, it gave us a credibility we wouldn’t have had if we’d said we’d just come from Philadelphia.”

Watch Asleep at the Wheel’s 2020 Paste session below.