The last time I saw Billy Joe Shaver play a full set of music was at the Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion in 2014. At that point, the poet laureate of the Texas honky tonks was 75 and had already defied every actuarial table in existence. He had lost two fingers to a lumber mill; he had lost his wife and son to cancer and heroin respectively. He had survived several divorces, assault-with-a-gun charges and a heart attack—even the music business. So when he sang, “I’m going to live forever,” that day, it was no idle boast.

Forever finally ran out Wednesday morning, when Shaver died of a stroke at home in Waco, Texas, at age 81. But if you go back and listen to the original version of “Live Forever” on Tramp on Your Street, the terrific 1993 album by Shaver, the duo of Billy Joe and his son Eddy, he explains what he meant by the title in the first verse.

“You’re gonna miss me when I’m gone,” Billy Joe sang over Eddy’s sparkling guitar picking. “Nobody here will ever find me, but I’ll always be around. Just like the songs I leave behind me, I’m gonna live forever now.” And he was right. Even after his body is gone, his songs will be with us as long as people are listening to country music.

That’s because his songs are so sturdy in their craftsmanship and so timeless in their observations that they seem unmoored from any particular era. “When I have a song that I’m not sure is right,” Shaver told me earlier that summer, “I’ll take it and sit down and write it just like I was writing a letter to someone I care about or someone I’m trying to impress. In a letter, you have to make sense all the way through. You can’t just go off. Sometimes I have to change things to make more sense or say the same thing with fewer words. That’s the test.”

Even if you’re not a fan of Shaver’s “chunk of coal” tenor, you’ve probably admired his songs in the handsomer voices of Willie Nelson (“Hard To Be an Outlaw”), Johnny Cash (“Georgia on a Fast Train”), Waylon Jennings (“Honky Tonk Heroes”), Emmylou Harris (“Old Five and Dimers (Like Me)”), Patty Loveless (“When the Fallen Angel Flies”), Bobby Bare (“Ride Me Down Easy”), Elvis Presley (“You Asked Me To”) and John Anderson (“I’m Just an Old Chunk of Coal (But I’m Gonna Be a Diamond Some Day”).

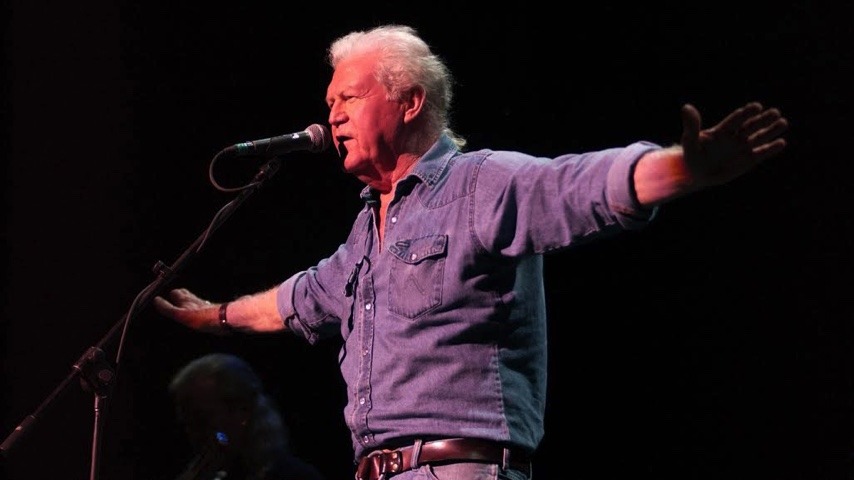

Myself, I enjoyed Shaver’s voice. For what it sacrificed in range and tone, it compensated with an unstudied enthusiasm and grinning irreverence for everything—not the least himself. That afternoon in 2014, he stood on a stage that straddled the Tennessee/Virginia border in Bristol, the “Birthplace of Country Music.” With his faded denim shirt sleeves rolled up and his now-snowy hair spilling out of a battered brown cowboy hat, he began the show with “Wacko from Waco,” his musical defense of the time he shot a man at Papa Joe’s Texas Saloon in Lorena in 2007.

“He was trying to shoot me,” Shaver sang with backing from a tight little rhythm section, “but he took too long to aim. Anybody in my place would have done the same. I don’t start fights, I finish fights; that’s the way I’ll always be. I’m a wacko from Waco; you best not mess with me.” When he got to the title line, he turned his hat sideways and crossed his eyes to turn himself into a crazy-man cartoon. By poking fun at himself, he provided the perfect antidote for the song’s macho bluster. That mixture of irreverent wit and non-conformist attitude informed most of his songs.

“What really happened,” Shaver told me, “was the guy shot at me a couple times, and I returned fire and hit him between the mother and the fucker right in the mouth. He dropped both the gun and the knife and said, ‘I’m sorry.’ He should have said that when we were still inside. I’m not proud of it, and I’m sure he’s not proud of it. He’s still got that bullet in his mouth.

“Willie wrote a song called, ‘Give Me My Bullet Back,’ and asked me to sing it, and I said, ‘No way am I going to touch that.’ But he helped write the last part of ‘Wacko from Waco’ and that made it a better song. When a story becomes a song, it becomes something different, something funny. ‘Wacko from Waco,’ is a funny title and it takes the sting out of what happened.’”

In the fourth verse of “Wacko from Waco,” Shaver sings, “I was born in Corsicana. They said, ‘Billy can you do it.’ I said, ‘Course I can. Just point it out and I’ll get right to it.’” Corsicana was a small farming town between Dallas and Waco, the same place where Lefty Frizzell was born. Shaver’s mother ran the Green Gables honky tonk there, and her son grew up on Hank Williams records in the juke box.

“I’d go out in the street and sell papers and sing without an instrument,” he told me, “and I sold a lot of papers that way. I’d go across the tracks every night to where the colored people were. A lady had a standup piano on her front porch, and I’d stand around and sing along. My grandmother would be waiting for me when I came home with a switch, but I kept going back anyway.

“They were doing Jimmie Rodgers songs because they thought he was Black. When they found out he wasn’t Black, they stopped singing him. I believe if Jimmie were alive, he’d have written ‘Honky Tonk Heroes.’ That’s a compliment to myself, but I believe it’s true. It’s not that I learned from Hank, Jimmie and Lefty so much as I was inspired by them and found a place among them.”

He dropped out of school after the eighth grade, but he didn’t let that stunt his intellectual curiosity or his gift with words. He had a tough time getting others to take him seriously, but he wouldn’t give up. As he sings in his song, “Georgia on a Fast Train,” “I wasn’t born no yesterday, got a good Christian raisin’ and an eighth-grade education, ain’t no need in y’all a treatin’ me this way.”

“I went into the Navy as soon as I turned 17,” he continued. “I got my fingers in a log-cutting machine at Cameron Mills that took off two fingers at the knuckle when I was 21 in Waco. I’ve been taking good shorthand ever since—I had to get that joke in there—but there was nothing else I could do. I had a wife and young baby. I rodeoed a bit. She didn’t like that, so she left me and I was on my own. I needed to make some money, and I couldn’t get a regular job, so I turned to music.”

Waylon Jennings heard Shaver sing in Texas in 1972 and encouraged the latter to come see him in Nashville. When Shaver showed up six months later, Jennings had forgotten the promise and wasn’t in the mood to hear songs by a nobody from nowhere. But Shaver wasn’t easily shaken, and he kept chasing after Jennings. When the nobody finally cornered the star at RCA’s Studio A, Jennings was surrounded by a posse of bikers.

“’What do you want?’” Waylon asked,” said Shaver during a 2018 interview at the Country Music Hall of Fame. “I said, ‘I want you to listen to my songs or I’ll kick your ass right here in front of God and everyone.’” The bikers moved in menacingly, but Jennings stopped them and motioned Shaver into a side room. “He said, ‘Okay, I’ll listen to one song, and if I like it, I’ll hear another. If I don’t like it, you’re gone.’ So I played ‘Ain’t No God in Mexico.’ He said, ‘Okay, play me another one.’”

Jennings listened to every song Shaver had, and he recorded 10 of them on his next album, 1973’s Honky Tonk Heroes. It worked out well for both men. Jennings had a top-10 country single with “You Asked Me To” and a top-15 album. More importantly, the album completely recast his image and kicked off the outlaw-country movement. And Shaver established himself overnight as an important country songwriter.

“They started calling us outlaws,” Shaver told me. “They might as well have called us outcasts, because that’s what we were. They didn’t want anything to do with us. Everyone else was wearing sequins, and we were wearing old jeans. Their music was sweet and polished, while ours were rough and rowdy. They didn’t want anything to do with us, and then, when we started having hits, they did. I give Kris [Kristofferson] a lot of credit for that too, because he was writing all those songs at the same time.”

Unlike Jerry Jeff Walker, another Texas singer-songwriter who died this month, Shaver didn’t coast on his laurels after his mid-’70s success. He continued to write terrific songs and make impressive records. He formed a duo called Shaver with his rock ’n ’ roll guitarist son Eddy. It sounded like a bad idea—marrying the father’s front-porch storytelling with the son’s Stratocaster blasting—but they figured out how to stay out of each other’s way and made some of the best albums of the father’s career.

Unfortunately, Eddy died of a heroin overdose on New Year’s Eve, 2000. The father had a hard time surviving that blow, but as he did with all his crises, he wrote his way out of it. He turned that impossible pain into the elegiac song, “Star in My Heart,” that he sang at every show the rest of his life.

“It’s easier to write the truth about yourself,” he told me, “rather than make up the truth about somebody else. I’m a real good writer, so I can make that work. I don’t like to speculate or make stuff up too much; I’d rather go ahead and write about what happened. It’s easier, like predicting rain when you’re in a thunderstorm. I’ve been writing since I was eight years old. I’ve been in and out of a lot of things; I’ve always had my eyes wide open and my ears wide open.

“It’s the cheapest psychiatry there is. I love writing; it takes a lot off my shoulders. Everyone should write. There’s no way you can lie to yourself; you can try, but you know better. When you get it down on paper, it’s like you’ve taken off a load and you feel lighter. Confession is good for the soul; at least it is for my soul.”