It’s always weird when a song you love goes viral. When I think of Wolf Parade’s anthemic “I’ll Believe in Anything,” I think of being 19 and clutching at the cheap green comforter of my dorm room bed, choking down furious sobs so my next-door neighbors wouldn’t hear me crying through the thin walls. I think of standing alone on Foss Hill at midnight, fingernails dug into the meat of my palms, my gaze cast up at the familiar sight of the Pleiades cluster and the line “Look at a place far away from here” ringing in my ears. I think of sitting at an old piano in an underground bunker-turned-practice-room, trying to suss out the song’s chords by ear as a last-ditch means of distraction from an increasingly unbearable year, always hitting the keys with unnecessary force whenever the “I’d take you where nobody knows you / And nobody gives a damn” refrain came back around. (Look, I know it’s ostensibly a love song, but it’s always been an outlet for sheer desperation for me—a soundtrack for that visceral, painful yearning for a life that is anything other than the one you’ve been living.) So it’s weird to hear that song as the accompaniment to triumphant, love-is-love TikTok edits of fictional gay hockey players, inexplicably reposted on the Instagram stories of the very people I’ve always associated that song with crying over. Funny, how life works.

I was three when Apologies to the Queen Mary came out, which means everyone else’s history with it technically predates my ability to read (sorry). I know the point of retrospectives is to, you know, retrospect, but if I reminisced on the music that made me in 2005, this would be an essay about The Wiggles. So when I first heard “I’ll Believe in Anything” in early college—at my dad’s recommendation, naturally—it wasn’t striking because I clocked it as a cornerstone of mid-2000s blog rock. It was striking because, when that scrambled little synth pattern came skittering in and Spencer Krug’s voice started howling its way up from the bottom of his lungs, it felt as if the meat of my chest had been carved out and filled with hot air, some desolate kind of hope clogging up my throat and making it hard to speak. In other words, I didn’t inherit Apologies as a reference point but as a working object, a tool that still functioned in 2020 just as well as it did 15 years prior. The trick of the album, I think, is that it’s just about as pinned to 2005 as anything possibly could be (Stereogum’s Ian Cohen called it “absolutely the most 2005 album” conceivable), but somehow, it refuses to stay there.

Over and over, these songs reflect and refract the same state of mind: restless, unsatisfied, slightly out of phase with your own life, pacing a room that doesn’t feel like it was built for you—but wanting it to be built for you so very badly. Wanting to make yourself someone it was built for, but not knowing how. When Krug yelps in that idiosyncratic voice of his about “sons and daughters of hungry ghosts,” he’s talking about his peers; I heard it and felt he was talking about mine. Sure, the scaffolding is different for my generation—less “refreshing music blogs between college classes,” more “refreshing five apps at once while the president legalizes hate crimes”—but the feeling at the album’s core hasn’t gone anywhere: You are here. You don’t want to be here. You’re not entirely sure where “there” is, only that it’s somewhere you might finally be able to breathe. And Christ, you’d do anything—believe in anything—to find it.

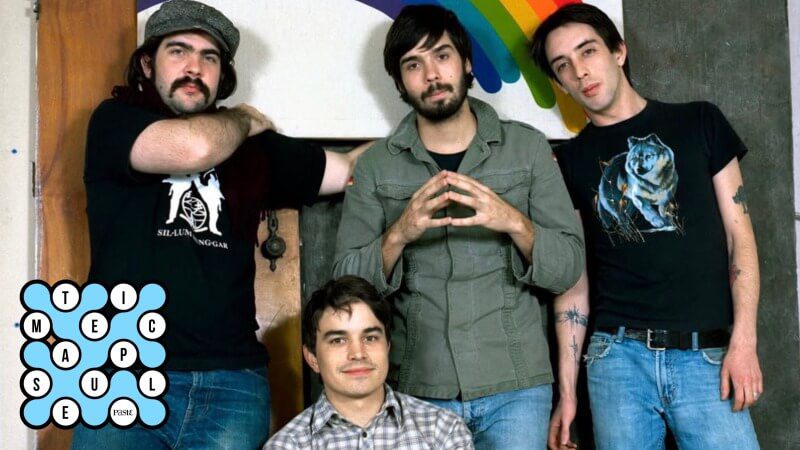

IN 2005, THOUGH, NOBODY KNEW this record as a retroactive lifeline for kids born after 9/11, let alone a TikTok sound. They knew it as the debut from a weird new band out of Montreal, that city every music writer suddenly decided was the center of the universe for about 18 months. Wolf Parade had technically only been a band for a couple of years by then—Spencer Krug and Dan Boeckner writing songs together in Krug’s apartment over a grimy bar called Barfly, enlisting drummer Arlen Thompson eight days before the band was set to play an opening gig for Arcade Fire, eventually adding electronics guy Hadji Bakara once things got serious enough to require someone whose job was “make it sound stranger.” It didn’t take long—at all, really—for the band to start making waves in the indie scene. (Oh, the things an Arcade Fire tie-in could do for you in the mid-2000s. Damn you, Win Butler, for being terrible.) The legendary label Sub Pop rapidly signed them; TIME’s Canadian edition called their debut one of the country’s “most anticipated indie albums”; Modest Mouse’s own Isaac Brock offered to produce and hauled them to Portland to record at Audible Alchemy. On paper, it’s the kind of origin story that makes publicists salivate: two gifted songwriters, one buzzy city, one famous adjacent act, one famous patron saint, one very hungry label. Then they finally released their debut—largely cobbled together from various re-recorded songs off their four already-released EPs—and the rest, of course, was history. Well, maybe not history; maybe just some good reviews (including a remarkable 9.2 from Pitchfork), modest sales, year‑end‑list appearances, and a long, quiet residency in the heads of people susceptible to its particular strain of beautiful agitation.

Apologies didn’t exactly blow up the culture on impact, in part because it didn’t launch a movement so much as arrive in the middle of one. In a moment when other Canadian bands like Broken Social Scene and Arcade Fire were making orchestral indie that sounded like it was meant for stadiums but was still technically being played in churches and bars and VFW halls, Wolf Parade showed up with something scrappier, more jagged, more likely to blow a gasket. Even then, people struggled to describe it without resorting to comparisons: “like a Ritalin‑deprived power‑Bowie,” “Springsteen filtered through a busted PA,” “Pixies rhythms and Frog Eyes vocals in a Canadian contraption,” and, inevitably, Modest Mouse (“Grounds for Divorce” always reminds me, for some reason, of “Gravity Rides Everything”). None of that really captures how the record feels when you’re alone with it, but it does get at the central fact that from the beginning, this was a band slightly outside whatever neat box you tried to put them in.

So maybe it’s fitting that when it came time to name their debut, they reached back not to some grand metaphor or announcement of their identity, but to the night they got thrown off a potentially haunted ship: the “Queen Mary” in the title is not Queen Mary I of England, but the the RMS Queen Mary, a retired British ocean liner that, in the mid‑2000s, doubled as a hotel, tourist attraction, and venue for the All Tomorrow’s Parties festival. Wolf Parade got invited to play, did the sensible thing—drank a heroic amount of free booze—and at some point in the night the group kicked down the locked door to the Winston Churchill Ballroom. Inside, they found an opulent, empty room just begging to be desecrated. Because the ship already had a reputation for being haunted, Bakara decided they should hold a séance to “manifest this era of Winston Churchill,” which somehow escalated into turning an oak table into a Ouija board with the help of a buck knife and some stolen décor. The conjured “spirits,” as he tells it, quickly became “pretty immature,” started “breaking stuff” and “throwing things overboard.” When the ship’s management finally intervened, the spectral perpetrators were nowhere to be seen, so despite the band’s protests that “it was just the spirits” (likely story), they were kicked off the boat. But whether or not the band actually summoned anything in that ballroom almost doesn’t matter—the album they named after the ship came back full of ghosts anyway.

GHOSTS ARE EVERYWHERE on Apologies to the Queen Mary, both explicitly and implicitly. “Dear Sons and Daughters of Hungry Ghosts” sees Krug name his whole generation after a Buddhist legend that posits that the “hypocrites and liars go” to a level of hell that turns them “into hungry ghosts…like Tantalus in Greek mythology: he can’t eat or drink, but he’s always hungry or thirsty.” That, Krug insists, is us—always starving and never satisfied—atop la‑la‑las and handclaps trying to pass that spiritual malnourishment off as something you can dance through. “Same Ghost Every Night,” with its “strange, constant blue” and walks taken just to hear your own breath, is Boeckner writing about a rural outpost that felt like it wanted to swallow him whole—family tragedy humming in the background, the woods pressing in on all sides, the sense that you are a tiny, doomed colony of humanity surrounded by something vast and indifferent. “Shine a Light” turns a hellish routine—insomnia, night shifts, “boring hours in the office tower,” that bus back home when you’re “barely alive”—into a hymn for people who keep going anyway, hearts “waiting for something that’ll never arrive.” “There is an awful sound, this haunted town / Some ghosts sink, some will get called to the light.” Right on the heels of “Shine a Light,” “Dear Sons and Daughters” follows with its pub‑chant stomp and talk of hungry ghosts, and then, without so much as a pause, “I’ll Believe in Anything” detonates the whole thing into a love song about wanting to be carried somewhere—anywhere—else. Sheer exhaustion, spiritual or otherwise, can turn into a kind of wild, reckless grace if you push it hard enough. That three‑song run is the record’s spine: work, hunger, escape, in quick succession. (It is also, not unrelatedly, one of the greatest three-song runs of the century.)

Even the relationship songs feel haunted by absence more than presence. “Grounds for Divorce,” which Krug insists is “just about breaking up,” hangs everything on trivial preferences—bus brakes versus imaginary whales, cloud‑watching versus radio static—and then keeps returning to that dead darling, that wedding cake of a relationship that crumbled upon contact. “We Built Another World” is ostensibly about getting drunk at a party and thrown out for breakdancing and fighting, but by the time Boeckner’s singing about lights pinning “the ghost to the street” and a world built by “hanging ghosts from the trees,” it feels like a vision of all the possible lives that might have been built out of nights like that and weren’t; a dream of escape from our “Modern World” that we struggle daily to actualize. “Dinner Bells” stretches that feeling out until it starts to blur, seven‑plus minutes of fall‑afternoon corniness and end‑times imagery that Krug kept precisely because it felt a little embarrassing instead of safely cool. Closer “This Heart’s on Fire,” which Boeckner calls completely autobiographical, can’t quite decide if it’s a love song or a grief song: “I am my mother’s hen / And left the body in the bed all day” sits right next to “you’re my favorite thing, tell it everywhere I go,” all of it attached to a hopelessly hopeful refrain of “It’s getting better all the time.”

There’s an interesting divide between body and soul throughout the record—“their hearts are dead but the body don’t mind”—yet, curiously, there’s less of one between body and body. “We Built Another World” begins with two people literally chained at the wrist; “I’ll Believe in Anything” is a love song of frenzied unification: give me your eyes, your blood, your bones, your voice, your ghost. “Fancy Claps” promises “When I die, I’m leaving you my feet / When you die, you can stand up for me.” Two spirits, one mouth—and wouldn’t you know it, Apologies itself functions the exact same way: two songwriters with different obsessions trying to cram their mid‑twenties crises into a single 47‑minute body.

THE SPLIT IS SIMPLE ON PAPER. Half the songs belong to Spencer Krug, the guy who writes about singing to cracks in crossbeams, dinner bells for the end-times, cupping water in hands with holes in them, people building houses inside each other. The other half all belong to Dan Boeckner, whose songs are full of highways, office towers, “modern world” motorways, the grieving aftermath of mortality, small towns that want to spit you out, cities that don’t care if you live or die. Critics love to frame it as Bowie vs. Springsteen: Krug as the glammy, metaphor‑addicted dramatist; Boeckner as the ragged working‑class romantic with an ear for a three‑chord stomp. And sure, you can hear that when “You Are a Runner and I Am My Father’s Son” barrels straight into “Modern World,” one voice wailing about becoming his father over an off‑kilter piano pattern, the other immediately snapping back, “I’m not in love with the modern world,” in a more grounded drawl.

Krug, for his part, feels less like he’s performing than sprinting alongside some feeling that keeps threatening to outrun him. His voice lurches and cracks and claws its way up a melody, vowels stretching out until they’re half-feral or cut short so the staccato hits like a truck. He’s like a rubber chicken strangled at the neck, and I mean that entirely as a compliment—his skittery songs are some of the most immediate and memorable on the record, in part because of the sheer viscerality of his voice. Boeckner, by contrast, is a more recognizable rock voice: a little ragged, a little scorched around the edges, a jaded weariness bleeding through even his sharper barks. His songs are the come-downs after Krug’s anxious, nervy brain-scratchers, grounding you just enough for Krug’s follow-up track to catch you off-guard once more.

But even then, that division never stays clean for long, which is part of what makes the record feel so alive. The tracklist alternates their songs almost one‑for‑one, and there are moments where they literally share a mic—“We Built Another World” in particular, with Boeckner narrating the Halloween party and the first Montreal snow while Krug cuts in on the chorus with “I had a bad bad time tonight… ’cause bad things happen in the night,” turning a single evening into a miniature argument about whether the world they built together is salvation or trap. Even when a song is clearly one guy’s on the lyric sheet—“Same Ghost Every Night” tracing Boeckner’s “Lovecraftian” small‑town dread; “Dear Sons and Daughters of Hungry Ghosts” naming Krug’s generation after beings who are always starving and never satisfied—they slot together so tightly that you end up hearing them as two angles on the same problem. One writes about forests that don’t care if you live or die; the other writes about hands and fists and what to do when God’s plans have clearly gone off the rails. Both are trying to figure out how to keep moving when you’re not sure you believe in anything that was handed to you.

You can hear that question in the way the album is bookended. It kicks off immediately with the stark drum crashes and lurching piano of “You Are a Runner and I Am My Father’s Son,” a number dedicated to the sick certainty that you are on track to become someone you never wanted to be, someone you’re all too familiar with. It ends with “This Heart’s on Fire,” Boeckner insisting “Sometimes we rock and roll / Sometimes we stay at home and build a life” then repeating that “It’s getting better all the time” mantra until it sounds less like optimism than self‑hypnosis. Between those poles—inheritance and invention—the rest of the record thrashes around trying to decide who to believe, or whether to believe at all.

Part of why all of this lands as hard as it does is the way the band chose to frame and soundtrack their own hauntings. They recorded most of the album in Portland with Modest Mouse’s Brock, but when some of the mixes came back too clean, they hated them enough to haul the tapes back to Montreal and start over on a home computer. “Shine a Light” even had to be completely re-tracked after the original multitracks went missing; the version on the album is a Frankenstein built on a Mac G3 in their jam space, with Tim Kingsbury on bass and whatever mics they could scrounge up. Krug has talked about running his keyboards and vocals through “weird processing” until they sounded warped, hissy, and slightly wrong, closer to how the band actually heard itself. Isaac reportedly told them the new mixes “sounded like shit.” They apologized to him, the way they’d already apologized to the Queen Mary, and kept the mixes anyway, which, fortunately, is why the album still sounds as raw and jagged and off-kilter as it does. (Krug has said he still prefers some of the original EP renditions of Apologies to the Queen Mary tracks anyway—“Dear Sons and Daughters” in particular—which only deepens the sense that this record is a compromise between how it sounded in their heads and how it ended up on tape.)

IT’S ONE THING TO WRITE about “an awful sound, this haunted town” that refuses to be quiet; it’s another to make the record itself feel like it’s bleeding at the edges. Arlen’s drums on “You Are a Runner and I Am My Father’s Son” don’t line up politely under the piano, they jab at it; Krug remembers deciding not to “fix” the awkward rhythm because he liked the friction. Bakara’s theremin and the delay‑drenched guitars on “Same Ghost Every Night” make it feel like the song is being played down the hall from you in an empty house you’re not supposed to be in. The video‑game synths and randomized arpeggiator at the beginning of “I’ll Believe in Anything” are literally a Roland Jupiter‑4 set to a C‑chord pattern and cranked until it sounds like the machine is jittering itself apart. It’s not just that the lyrics are about spiritually starving ghosts and spiritually devoid landscapes; the recordings themselves feel unsettled, like they could come unglued at any point.

Which brings us back to “Dear Sons and Daughters,” which Krug wrote on a piano he was borrowing from Arcade Fire’s practice space, in a room he and his band were only temporarily allowed to inhabit. He remembers the moment a descending right‑hand melody suddenly glued the song’s parts together, turning it from a jam into something worth keeping. The lyrics came later, in that tiny apartment above Barfly. He starts with a hand, turns it into a fist, turns that into a plan, shrugs and says, “It’s the best that I can do.” Then he flips the old coping mechanism—“it’s in God’s hands”—on its head by spitting out “God doesn’t always have the best goddamn plans, does he?” and spends the rest of the track trying to invent plans of his own: new bells, new songs, new ways to trick “the people” into thinking anything. It’s a song about needing to believe in something but distrusting every available authority, including yourself.

When Boeckner writes “Modern World” about walking around a metropolis he can’t quite afford, hating its motorways and automation and “lies to fill up your eyes,” he isn’t thinking about my 20-something peers doomscrolling through climate reports and anti‑trans legislation between Zoom classes in the 2020s. But the albums’ pervasive sense that you are living in a system that will keep humming along whether or not you manage to get out of bed, that no one in charge particularly cares if you disintegrate, remains wholly intact. Writers have been bemoaning modernity, with its technology and bureaucracy and apathy, for centuries. If Wordsworth’s gripe was that “the world is too much with us; late and soon,” Boeckner’s is the same plus fluorescent lighting and public transit, and mine is that it’s doing all that while rotting our brains with mindless 10‑second clips and turning every panic into a product. It’s the same human impulse, but as the years accumulate, so does the detritus of living in their wake. That’s the real magic of Apologies: it captured a very specific 2005 malaise on tape without ever fully tethering itself to that year. After all, if Krug’s generation was made up of hungry ghosts, it’s mine who are their sons and daughters.

IN THE YEARS AFTER Apologies to the Queen Mary, Wolf Parade did the sensible thing and refused to make it again. At Mount Zoomer and Expo 86 get weirder, more inward, harder to use as mixtape fodder; the band goes on hiatus, pursues side projects, then comes back, gets the deluxe reissue treatment, does the full‑album tours, enters the phase of a life cycle where your debut gets called “canonical” in thinkpieces written by people who were in kindergarten when it came out (read: yours truly; sorry about that). Krug and Boeckner both go on to make great, stranger records elsewhere, but none of them quite hit this particular balance of grit and immediacy again, which in hindsight makes Apologies feel even more like a one‑time alignment of planets. The record itself doesn’t seem especially bothered, though. It just keeps doing what it’s always done: sitting there waiting for whoever needs it next, ready to be reinterpreted as an eclectic mid-aughts touchstone, as Canadian‑indie time capsule, as coming‑of‑age manual, as hockey‑slash TikTok soundtrack. Hell, thanks to Heated Rivalry, it’s even being reissued now (Wolf Parade, if you see this, feel free to send one my way).

This is maybe why the song’s current burst into virality doesn’t bother me as much as I thought it would. Like, you know what? Why not set a clip of a fictional hockey star making out with his boyfriend on ice to “I’ll Believe in Anything”? My personal reading be damned, Krug did say he wrote it as an “apologetic love song” in the midst of trying to make amends after hurting someone, lyrics and music arriving at the same time on a stranger’s abandoned piano. Then Wolf Parade turned it into this howling, rickety juggernaut built on random arpeggios and desperate promises: I’ll give you my life. I’ll take you where nobody knows you. I’ll hand over all the olive trees. I’ll believe in anything, if you’ll just come with me. I will believe in something better than this, even if I’m not sure I should.

When I put it on now—at 24, no longer crying into a dorm comforter but still, embarrassingly often, pacing rooms that don’t feel like they were built for me—it doesn’t feel like I’m borrowing someone else’s nostalgia so much as checking in with an older ghost who happens to speak my language. That’s what a good haunting does, I suppose: it keeps showing up in new houses, rearranging the furniture. The scenery has changed; the algorithms have gotten worse; the modern world has found no shortage of new ways to be unbearable. Still, every time that chorus crests, I feel the same old floor drop out beneath me, the same old air rushing in, the same old half‑terrifying sense that there might, against all evidence, be a way to live that doesn’t hurt this much. I don’t believe in much these days, but I’m trying very hard to believe in that. And if it takes sexy TikTok fancams to make the rest of my generation feel the same, then so be it. Apologies to the Queen Mary is worth it.

Casey Epstein-Gross is Associate Editor at Paste and is based in New York City. Follow her on X (@epsteingross) or email her at [email protected].