Growing up in Atlanta in the 1970s and ’80s, “Southern rock” meant a very specific thing: long-haired bands like Molly Hatchet, the Allman Brothers and Lynyrd Skynrd playing extended guitar solos with enough bluster to pick a fight at any smoky roadhouse. It was part country redneck, part psychedelic hippie, and it dominated the FM radio stations of my childhood (looking at you 96 Rock). By the ’80s, Southern rock meant ZZ Top, Georgia Satellites and The Black Crowes, reviving the guitar licks of their forebears for a new generation. But it was also starting to mean something else. In college towns like Athens, Ga., and Winston-Salem, N.C., a distinct Southern jangle was emerging, mixing the post-punk of New York, the pop of Big Star, and the roots music that bands like R.E.M., Let’s Active and The dB’s were weaned on. The branches of Southern rock began to creep outward. Today, “Southern rock” means everything from the earthy synths of My Morning Jacket to the future soul of The Alabama Shakes.

But the origins origins of rock in the South also go back much further than Duane Allman playing guitar for the R&B hitmakers at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals in the 1960s. Bo Diddley, Little Richard and Fats Domino were among the first musicians to put Southern cities on the rock ‘n’ roll map. They were quickly followed by Southern icons at Memphis’s Sun Studio like Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Johnny Cash, whose early singles were as much rockabilly as country.

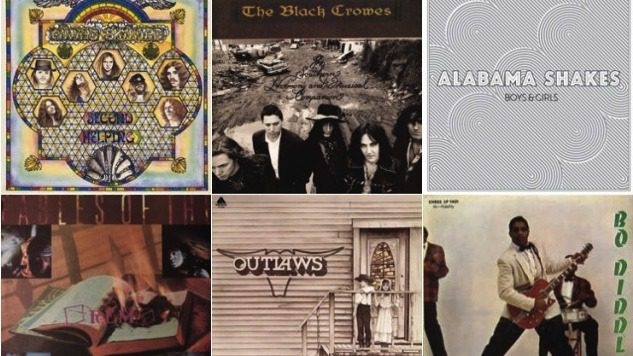

So when we compiled the 50 Best Southern Rock Albums of All Time back in 2018, we made sure the results were a little broader than the usual suspects. As long as the music was undoubtedly Southern (from Texas to the Carolinas, Kentucky to north Florida) and undoubtedly rock, it was on the table. That meant bands like The B-52’s and Of Montreal, who could have come from Mars, aren’t included. And bands like Creedence Clearwater Revival and Little Feat, who sound Southern but have no claim to these lands, are also absent. But the inclusion of early rock albums and modern torchbearers like Drive-By Truckers also means we didn’t have room for some roots rock standards like Atlanta Rhythm Section, Boz Scaggs and Dixie Dregs, which you’ll find on most every other list.

What follows are the Best Southern rock albums as voted by Paste’s music editors and writers, after long debates on what should qualify. As always for these lists, we limit each act to two albums. We think this approach results in a more interesting list, celebrating all of the South’s contributions to rock ’n’ roll. And you can tell us what we missed on our Facebook page. —Editor-in-Chief Josh Jackson

[Editor’s Note: This list was updated from its original publish in February of 2018]

Here are the 50 Best Southern Rock Albums of All Time:

50. Sir Doug and the Texas Tornados: Texas Rock for Country Rollers (1976)

Is Texas really part of the South? It depends on who you ask, but the answer is no. And yes. It depends. During his 30-plus-year career, Doug Sahm embodied that conundrum, melting the full range of Texan musical idioms—country, blues, Tejano, rock—into a singular (and singularly powerful) body of work. You’re probably familiar with his ‘60s band, The Sir Douglas Quintet, and might remember his early ’90s supergroup, The Texas Tornados. In 1976 he crammed those two band names together and made what might be his finest album, squarely within either the Southern-rock or country-rock traditions. It’s a laidback, ramshackle country-blues affair, with some of Sahm’s best originals (including “Give Back the Key to My Heart” and “You Can’t Hide a Redneck (Under That Hippy Hair)”), a cover of the country classic “Wolverton Mountain,” and a medley of Gene Thomas songs. —Garrett Martin

49. North Mississippi Allstars: Electric Blue Watermelon (2005)

Luther and Cody Dickinson, the sons of legendary Memphis producer, songwriter and pianist Jim Dickinson, brought a punk-rock spirit to the Southern-rock lyricism of the Allman Brothers and reached beyond the usual influences of the Mississippi Delta region to embrace those of the state’s Hill Country: the African-sounding music of Otha Turner’s cane fifes and the droning blues vamps of R.L. Burnside. On their fourth album, those roots blossomed into the Dickinson sons’ first monumental songs, which fit in comfortably with the three Turner originals. This recording pulls off the neat trick of sounding untraceably old and urgently new at the same time. —Geoffrey Himes

48. Kentucky Headhunters: Pickin’ on Nashville (1989)

If ever there were an album that established a brand, the debut from the Kentucky Headhunters would certainly qualify. It not only marked a real revival of true Southern rock, but gave the band its initial success. Pickin’ on Nashville spawned four successful singles—“Walk Softly on This Heart of Mine,” “Dumas Walker,” “Oh Lonesome Me,” and “Rock ‘n’ Roll Angel,” earning them a Grammy, two CMAs and top honors from the Academy of Country Music. They would be hard-pressed to achieve those distinctions again, and radio’s love affair with the band was short-lived due to the fact they proved too rocking for country and too country for rock. —Lee Zimmerman

47. Adia Victoria: Silences (2019)

Do the blues count as southern rock? Maybe not always, but they definitely do when Adia Victoria is singing ‘em. She’s a Nashville-based singer/songwriter who was raised in South Carolina and grew up on Flannery O’Connor and Angela Davis. Her excellent 2019 album Silences is a southern album through and through: Victoria channels soul legends like Aretha Franklin and Nina Simone, rock heroes and country singers of old. Maybe her music isn’t southern rock in the conventional definition, but it is in fact rock music from the Deep South. This firecracker-of-an-artist is worth an edit. —Ellen Johnson

46. Webb Wilder: It Came from Nashville (1986)

Although Webb Wilder was born in Hattiesburg, Miss., his solo debut focused on an auspicious homage to Nashville, the place he came to call home. The mix of deadpan humor and everyday happenstance resulted in a kind of brash irreverence, an attitude that offered the decided impression that he was given to a skewed perspective. Musically, it echoed any number of precedents—Elvis, Jerry Lee and Steve Earle (whose song “Devil’s Right Hand” Wilder rendered with added urgency), chief among them. Likewise, rockabilly, cow punk and country caress were combined in equal measure, making for a rowdy and rousing rave-up that precludes any kind of passive encounter. A definitive view of Music City from a doggedly determined point of view, It Came from Nashville fuses past with present in wholly irreverent ways. —Lee Zimmerman

45. Rosanne Cash: The River & the Thread (2014)

With a voice like good claret or damp moss, Rosanne Cash’s singing is something to sink into. Surrender to the tones, mostly dark, but marked by the occasional glimmer of light, and let the emotions they contain seep inside. For Cash, the emotions on The River & The Thread are complex and tangled, especially the Grammy-winner’s own difficult relationship with the South, her roots and her own musical journey. What emerges, beyond a woman grappling with a legacy as much in the rich bottom land as her father Johnny’s iconic presence as the voice of America, is a knowing embrace of the conflicts in the things we love. The 11-song cycle is mostly a meditation on the textures and musical forms that emerged South of the Mason Dixon. Finding not just resolve, but acceptance is a gift. Cash, who’s sidestepped her heritage, and eschewed a career as a country star with 11 Number Ones, a marriage to a country writer/producer/artist Rodney Crowell and the city/industry where she found prominence, savored her wandering and the Manhattan life she built. With The River & The Thread, she comes home with the warmth reserved for knowing where we’re from. As powerful a witness for the region—Memphis, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas—as it is a lovely quilt of musicality, braiding blues, folk, Appalachia, rock and old-timey country, this is balm for lost souls, alienated creatures seeking their core truths and intellectuals who love the cool mist of vespers in the hearts of people they may never encounter. —Holly Gleason

44. Johnny Winter And: Johnny Winter And (1970)

A decade before Stevie Ray Vaughan unleashed his Texas Flood, the Lone Star gunslinger to be reckoned with was Johnny Winter, an albino from Beaumont who put the blues world on notice with his first two albums, 1969’s The Progressive Blues Experiment and Second Winter. With muscular, rapid-fire guitar lines and an imposing tenor growl, Winter was quickly embraced as an heir to the Kings—B.B., Albert, Freddie—and a quintessential Texas outlaw. For his third record, he made an abrupt turn, assembling a new band co-starring himself and the pop-oriented guitarist Rick Derringer, and releasing Johnny Winter And, a mix of Derringer-derived rock songs and Winter’s searing blues. One of the great Southern Rock blueprints, Johnny Winter And puts a roadhouse spin on the riff rock of the era—Zeppelin, Hendrix, Santana. Opener “Guess I’ll Go Away” rides a Cream-like ascending guitar line. “Am I Here” slows it down with a jangly lead, organ, and some classic-rock harmonies, leading into the slide-happy “Look Up.” Elsewhere, a cover of Traffic’s “No Time to Live” and an early version of Derringer’s “Rock and Roll, Hoochie Koo” cemented Winter’s rock bona fides. —Matthew Oshinsky

43. Wet Willie: Keep On Smilin’ (1974)

From Macon by way of Mobile, Wet Willie were ‘70s mainstays on Capricorn Records, which was essentially the Motown for Southern rock. Compared with such labelmates as The Allman Brothers Band and The Marshall Tucker Band, Wet Willie were a tight, concise pop band that combined blue-eyed soul and Southern boogie woogie into slickly produced four minute pop songs. Their third album, Keep On Smilin’, is best known for the title track, an AM Gold-ready shot of pure pop positivity that cracked the top ten in 1974; all together the album is a great example of the more unabashedly commercial-minded and crowd-pleasing side of Southern rock. —Garrett Martin

42. St. Paul and the Broken Bones: Half the City (2014)

St. Paul & The Broken Bones is not a band that’s easily ignored. The Birmingham-based sextet gets in your face—literally—during shows, and managed to transfer that intensity to each of the 12 songs on their debut LP Half The City. With strong roots in the Pentecostal church, frontman Paul Janeway seems to deliver entire sermons in three-and-a-half-minute opuses throughout the record. He narrates entire parables like “Grass is Greener” and “Like A Mighty River” in his emotive tenor that evokes both preacher and crooner. And the built-in, two-man brass band arrangements add depth, rhythm and soul to Half The City, especially on tracks like “Broken Bones & Pocket Change” and “Sugar Dyed.” Inspired by funk and R&B acts like Prince, Sam Cooke and Otis Redding, St. Paul & The Broken Bones understands the power music has to make you weep, dance and rejoice, sometimes all at the same time; each track on Half The City serves one or more of those roles. So while the band released its first EP, Greetings from St. Paul & The Broken Bones, in 2013, and two more albums later this decade, it’s this full-length debut that still serves as the ultimate conversion for believers and heretics, alike. —Hilary Saunders

41. Elvis Presley: Elvis Presley (1956)

Released in 1956, Elvis Presley’s self-titled debut was far more than a record: It was the vehicle for the creation of one of pop culture’s greatest icons. Featuring tracks from Presley’s Sun Studio sessions in Memphis and RCA studio recordings in both New York and Nashville, Elvis Presley introduced Presley’s smooth, seductive vocal style to the world. Hits like “Blue Suede Shoes” and “I Got a Woman,” though written by Carl Perkins and Ray Charles, respectively, would soon become synonymous with Presley’s sex-symbol status. Young women around the globe were never the same, and neither was rock music in the South. —Loren DiBlasi

40. Georgia Satellites: Georgia Satellites (1986)

Every class needs a clown, and The Georgia Satellites played the role with panache among their Southern rock peers. Though the band had serious musical chops and an appealing fondness for blaring, dirty-sounding guitar riffs, singer and primary songwriter Dan Baird had a roguish streak that resulted in the band’s 1986 single “Keep Your Hands to Yourself.” It it was their biggest hit, but that mischievous undercurrent runs through most of Georgia Satellites, which is full of songs that are smarter than they appear. Along with the greasy rocker “Red Light” and guitarist Rick Richards’s vocal turn on “Can’t Stand the Pain,” the album includes the raucous harmonies of “Battleship Chains” by Baird’s kindred spirit, Terry Anderson. — Eric R. Danton

39. Drivin’ n’ Cryin’: Mystery Road (1989)

Though it might have lacked the punk freedom of their first two albums, Scarred But Smarter and Whisper Tames the Lion, Mystery Road is where the Atlanta rock band fully embraced their Southern roots for a more unforgettable sound. Starting with the fiddles on “Ain’t It Strange” and Southern crunching guitars of “Toy Never Played With” to the Red Clay power-ballad “Honeysuckle Blue” and culminating in the bad-boy anthem “Straight to Hell,” this was the pinnacle of Southern rock in the late 1980s. Even R.E.M.’s Peter Buck showed up to play some dulcimer. Kevn Kinney was a folk troubadour at heart, but bassist Tim Nielsen, guitarist Buren Fowler and drummer Jeff Sullivan all added more than a touch of Allman Brothers and Skynyrd influence to the point that follow-up Fly Me Courageous had the band touring in leather and playing arena rock. But on this album, the balance between punk beginnings, country leanings and ’70s Southern FM radio adoration was just about perfect. —Josh Jackson

38. James Luther Dickinson: Dixie Fried (1972)

There are many routes to discovering Jim Dickinson. As an in-house producer at Ardent Studios in Memphis in the ‘60s, he later co-founded The Dixie Flyers, a group of session musicians who replaced the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section as Atlantic’s preferred backing band, where he played on early ’70s records for Aretha Franklin, Sam & Dave, Jerry Jeff Walker and more. In the mid ’70s he worked with Big Star and Alex Chilton on the gloriously ramshackle albums Third/Sister Lovers and Like Flies on Sherbert. He traversed both mainstream and underground throughout the rest of his career, working with bands as diverse as the Replacements, Primal Scream, the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Bob Dylan. Between all this he still found the time to put out a half-dozen solo albums, the first of which, 1972’s Dixie Fried, can sound as unhinged as those Big Star and Chilton albums. It’s a woozy trip through a variety of Southern traditions, from folk to country to rockabilly, with the unifying factor being Dickinson’s peculiar intensity. The album’s standout track, a dizzy, stumbling version of Dylan’s “John Brown” that constantly seems to be swallowing itself, almost recalls Pere Ubu, if they were from Memphis instead of Cleveland and played boogie instead of punk. It’s proof that even in the early ’70s there was a weirder, artier side to Southern rock. —Garrett Martin

37. Band of Horses: Cease to Begin (2007)

“Southern rock” has traditionally evoked muttonchops and the devil going down to Georgia, but the genre’s tapestry certainly includes the kaleidoscopic psychedelia of early R.E.M. and the reverb-limned keening of My Morning Jacket. Band of Horses arrived firmly aligned with the latter camp, but born of Seattle’s omnipresent rainstorms and attendant coffeehouse culture. Singer/guitarist Ben Bridwell, a born Southerner, convinced his bandmates to return to his native South Carolina, a place he fled after finding himself in a “whole bunch of trouble.” The band’s sophomore release, the Churchillian-titled Cease to Begin, marked a new chapter in Band of Horses’ development, as well as a shift in Bridwell’s writing, veering from the soft-focus impressionism toward a more narrative-driven style. More than anything, Cease to Begin represents the sound of a talented writer growing more comfortable in his skin and unafraid to name a song after ex-Seattle Supersonic Detlef Schrempf despite its elegiac, unrelated subject matter. —Corey DuBrowa

36. Brittany Howard: Jaime (2019)

On spoken-word breakdown “13th Century Metal,” Alabama Shakes frontwoman Brittany Howard repeats, over and over, “We are all brothers and sisters.” This sentiment of union is a thread that runs throughout Jaime’s 35 minutes, but Howard’s debut solo effort is also deeply personal. “I wrote this record as a process of healing,” Howard wrote in a personal essay upon the album’s announcement. “Every song, I confront something within me or beyond me. Things that are hard or impossible to change, words and music to describe what I’m not good at conveying to those I love, or a name that hurts to be said: Jaime.” She’s referring there to her sister Jaime, who passed away as a teenager. But as Howard also wrote, “The record is not about her. It’s about me.” These are love songs (perhaps written for her wife Jesse Lafser, with whom she recently moved to small-town New Mexico), spiritual songs, songs about the past, songs about the future and songs that react to and make sense of our present moment. On Jaime, Howard beautifully reckons with her personal past and shatters soul, rock and blues norms in an album that should go down as one of the most daring and inventive of the year 2019, maybe even the decade. —Ellen Johnson

35. My Morning Jacket: Z (2005)

Ask five fans what kind of music Kentucky’s My Morning Jacket play, and you’ll get five different answers. It’s “country-rock.” Or it’s “jam-rock.” Or it’s “space-twang.” The word “Southern” is often used as a modifier, and the word “reverb” is certain to be mentioned. But the labels frustrate My Morning Jacket, not because none of them apply, but because all of them apply at one time or another. It’s “rock ’n’ roll,” hold the hyphens, please. Frustration with the 2004 election, Jim James told Paste in 2005, ”[I’m] writing songs where I just feel really upset and angry, and I don’t know what to say all the time. So the chords are just crying for what’s going on.” Inarticulate frustration sounds like a flimsy base for songwriting, and perhaps it would be for another band, one that doesn’t rely on gorgeous pyramids of reverb vocals. But in “Wordless Chorus,” Z’s opening track, the song’s “ahs” get the point across better than language could. The album stretched the already expansive My Morning Jacket sound, while stripping out unnecessary elements and trimming some of the open-ended jamming. Everything from blue-eyed soul and Crazy Horse stomps to the Jacket’s trademark spacey textures fill Z’s 46 minutes, yet the album sounds decidedly different from its predecessors, and remains one of their best. —Reid Davis

34. Fats Domino: Rock and Rollin’ with Fats Domino (1955)

Antione Dominique “Fats” Domino Jr. got his start in music at age 14, playing piano in New Orleans bars under the tutelage of bandleaders like Billy Diamond, who gave the youngster his nickname. But it was his early singles like “Poor Me” and “All by Myself” that got him attention, first on black radio before his crossover hit “Ain’t That a Shame,” which reached #10 on the pop charts in 1955. Those songs and nine others were collected on his first LP, Rock and Rollin’ with Fats Domino, in 1955—seven years after his recording career began. Most of the songs were co-written with trumpeter and fellow Crescent City rock and R&B pioneer Dave Bartholomew, who also served as Domino’s A&R rep for Imperial Records. The album was also released in the UK and was one of the first black rock records to be embraced by a white audience, in part thanks to the easy boogie-woogie piano and cheerful nature and partly due to Domino’s ability to churn out catchy, bouncy, unforgettable melodies. —Josh Jackson

33. Molly Hatchet: Flirtin’ with Disaster (1979)

If you didn’t already know that Jacksonville’s Molly Hatchet occupied the harder extremities of Southern rock, with the most pronounced metal edge of any of the genre’s canonical bands, their album covers would’ve clued you in. They look like Dungeons & Dragons book covers. This one’s got some kind of battle axe-wielding viking trampling over bones and some kind of serpent. The D&D redneck is an understudied phenomenon. Hatchet started in ‘71 but didn’t get to release an album until ‘78, at which point Van Halen-style metal was ascendant (they actually lost out on their first record deal because the label signed Van Halen instead). Flirtin’ with Disaster, their second album, was produced by a metal guy, and it shows: if you replaced the Sabbath-style thump of Blue Oyster Cult or the Sunset Strip slickness of VH with some good ol’ fashioned chooglin’, it would sound just like this album. Yes, it’s the one with “Flirtin’ with Disaster” on it. It’s the name of Molly Hatchet’s best song and best album. The producer went on to work with Poison and L.A. Guns. —Garrett Martin

32. Carl Perkins: Original Golden Hits (1969)

Tennessee’s Carl Perkins could have been a contender. Though “Blue Suede Shoes” is remembered by most people as an Elvis Presley song, Perkins wrote it, recorded the definitive version and had the bigger hit with it. And if he hadn’t nearly died in a 1956 car crash, he might have capitalized on that initial success to become a huge star. As it was, he became a legend among musicians and record collectors, if not the general public. The Beatles recorded three of his songs, more than they recorded by any other outside writer on their original studio albums. This 1969 compilation collects the 11 best songs from Perkins’s 1955-1957 work for Sun Records, including “Blue Suede Shoes,” the three Beatles songs and the ultimate Southern-rock scorcher, “Dixie Fried.” —Geoffrey Himes

31. The Bottle Rockets: The Brooklyn Side (1994)

Imagine for a moment that the survivors of the Lynyrd Skynyrd plane crash in 1977 had decided to keep going and had replaced Ronnie Van Zant and Steve Gaines with The Clash’s Joe Strummer and Mick Jones. The reborn band would have had it all: redneck country-rock with in-your-face class consciousness and Cockney punk-rock with swing and guitar chops. It would have sounded a lot like the Bottle Rockets on this, their second album, The Brooklyn Side. The actual members of The Bottle Rockets hailed from Festus, Mo., and they sang about the blue-collar and flannel-shirt culture of Middle America from the inside out. When they sympathize with a welfare mother denounced by a fat-cat senator, they do so to a dobro-laced hillbilly tune and they point out that this mother’s “welfare music” is “Carlene Carter and Loretta Lynn.” But they also celebrate the exhilaration of new love with the irresistible guitar hook of “Gravity Fails” and the dizzying vocal/guitar harmonies of “I’ll Be Comin’ Around.” —Geoffrey Himes

30. Gary Clark Jr.: This Land (2019)

Both Adia Victoria’s album, Silences, and This Land, the third studio effort from Austin-born guitarist Gary Clark Jr., are the sound of the blues on the run. There’s a restlessness to this music that makes it feel exclusive to this moment, yet it’s tradition-honoring. And Gary Clark Jr. is a tried-and-true blues guitarist—a great one, at that. But he’s not a songwriter by trade. He can write lyrics, and in the past he’s written some decent-to-good ones. But his albums—where instrumentally masterful—sometimes lack on the content side. For This Land however, Clark goes out on a long limb both in terms of production and lyrics, and his game attitude pays off in a big way. Whatever Gary Clark Jr. lacks in narrative intuition he makes up for with six strings, once again proving himself to be one of the most impressive guitarists around. On “Pearl Cadillac,” Clark trades his anger for tenderness, beating his chest and proclaiming love while blistering blues guitar and a sea of strings provide a supportive backdrop. As on “I Walk Alone,” Clark is again recognizing his own flaws in love, debts owed to his partner. “I don’t wanna let you down,” he coos. “Oh, I only wanna make you proud.” Even on “The Guitar Man,” of which Clark is presumably the title character, he praises the woman (perhaps his wife, Nicole Trunfio, or their one-year-old daughter, Gia?) in his life: “Whether I’m standing on the corner with my heart in my hand, or everybody is listening to the guitar man, I can’t do it without you.” This Women’s History Month, Clark is asking the right question: where would we be without the strong women in our lives? —Ellen Johnson

29. Tony Joe White: Black and White (1969)

Learning that Creedence Clearwater Revival came from California and not the South is a bit like learning the truth about Santa Claus. It’s part of growing up, and something that you don’t want to believe at first. If oldies and classic rock radio did as much to keep Tony Joe White’s legend alive, we probably wouldn’t even need Creedence, much less feel betrayed when we realize they weren’t who we assumed they were. White was raised in Louisiana and since the ‘60s has been an acknowledged master of swamp rock, which is like if the blues, zydeco and hillbilly rock were all thrown into a huge pot that White then shouted nonsensical guttural exclamations into. Imagine CCR songs like “Suzie Q” and “Born on the Bayou” but made by a guy who actually was born on the bayou. White arrived fully formed on his first album, Black and White, which is full of these loping, monotonous basslines with White alternately soloing and moaning over them. The most famous song on here is “Polk Salad Annie,” which 1) is amazing, 2) is most famous for the version Elvis did in the ‘70s, and 3) could only have been written by an actual Southerner who had real-life experience eating polk salad. The only complaint I have about Black and White is that the 10 equally amazing songs on White’s other 1969 album, …Continued, aren’t on it. —Garrett Martin

28. Stevie Ray Vaughan: In Step (1989)

By 1989, Stevie Ray Vaughan had firmly established himself as the most electrifying blues guitarist of his generation with 1983’s Texas Flood and 1984’s Couldn’t Stand the Weather. But he was at something of a nadir as he approached his 1989 record In Step: Newly divorced and sober, having barely escaped the clutches of whiskey and cocaine, Vaughan set about recording In Step with clouds of doubt hanging over his career. Perhaps that’s why the album sounds so fresh. With new songwriting partner Doyle Bramhall at his side, Vaughan veered toward rock ‘n’ roll on rave-ups like “The House Is Rockin’” and “Scratch-N-Stiff,” putting more pianos and horns in his Texas gumbo and consequently earning more airplay on rock radio. He also faced his substance abuse head-on in crossover songs like “Tightrope” and “Crossfire,” the latter becoming his first and only No. 1 hit. With a new lease on life, Vaughan sounds energized and introspective on In Step, his inflammatory guitar still throwing sparks all over the place. He perished in a helicopter crash the following year. —Matthew Oshinsky

27. Alabama Shakes: Boys & Girls (2012)

Undeniably at the center of The Alabama Shakes’ debut record is Brittany Howard’s ascendant balladeering, which allows the Alabama Shakes to explore a sound made famous by the twin giants of Motown and Muscle Shoals. Her voice races from falsetto to growl to wail so quickly that she often changes direction mid-word, and that dynamism gives even the Shakes’ slowest songs a restless, animal energy that is impossible to ignore. Howard’s sound contains distinctive elements of Janis Joplin’s flint and spontaneity, Aretha Franklin’s depth and power and at times even the sweetness of Diana Ross. Despite the tendency of listeners to lump the band into the category of soul revivalists, Boys & Girls was best enjoyed not as an anachronism but as a fresh take on sounds from a bygone era. The Shakes looked to punk and hard rock as much as anything, and the melding of those influences with their rootsy, passionate appeal resulted in a style all their own, free of cynicism and brimming with vitality. —Eli Bernstein

26. Booker T. & the M.G.’s: Green Onions (1962)

In the summer of 1962, a 17-year-old organ player named Booker T. Jones was messing around at Stax in Memphis, where he, guitarist Steve Cropper, upright bassist Lewie Steinberg and drummer Al Jackson Jr. served as session musicians. When Stax president Jim Stewart hit the “record” button and released the instrumental “Green Onions,” one of the first multi-racial bands was born, and the Stax label had its first official LP release (prior Stax recordings had been issued on Atlantic Records) as well as its first No. 1 single. The full album, Green Onions, would set the template for that sweet Stax soul sound.—Josh Jackson

25. Black Oak Arkansas: High on the Hog (1973)

There are certain things you just have to learn to accept from Southern rock bands, especially ones from the ‘70s, that you wouldn’t be expected to tolerate from any other kind of music. (No, I’m not talking about the damn rebel flag; you never have to accept or tolerate that embarrassment.) High on the list: scrawny, long-haired white boys talking about sex, and how much sex they have, and how good they are at sex. That’s the stock in trade of Jim “Dandy” Mangrum, lead singer of Black Oak Arkansas, a band that hails from a town called, yes, Black Oak, Ark. Their fifth album, High on the Hog, is the best showcase for Mangrum’s backwoods vocals and the high-energy solos and riffing from the band’s three-guitar core. This is a record whose best three-song stretch includes such titles as “Happy Hooker,” “Red Hot Lovin’” and “Jim Dandy,” a cover of an R&B classic about a guy who—well, you can probably figure that out. There’s a certain level of raunch found in Southern rock that, along with such non-Southern fellow travelers as Aerosmith and Ted Nugent, influenced the sex-crazed hair metal of the ‘80s; High on the Hog, and Black Oak in general, overdoses on that raunch and then comes back for more. —Garrett Martin

24. Outlaws: Outlaws (1975)

Are you from the South? Do you own a musical instrument? There’s a great chance you were in Outlaws once. Tampa’s foremost country-rock guitar army has literally had about 50 members at this point in its history. Although still a potent live band, no matter who’s in it that week, there’ll always be an element of chasing that first gasp of glory. This is one of those bands whose first album (the first of 17 or so over the last 43 years) was its very best. The 1975 self-titled debut is bookended by two timeless classic rock-radio staples, “There Goes Another Love Song” and the 10-minute epic “Green Grass & High Tides.” Between them are eight other songs that easily could’ve been as huge, as they all follow a dynamite formula of catchy choruses with bright harmonies, alternating with extremely long, technically complex guitar solos by three guitarists who regularly rotate on lead. It’s somehow incredibly flashy but also humble and laid back, which is sort of what Southern rock should sound like. And really, as good as the album it is, it could just be one song, “Green Grass & High Tides,” and it’d still make this list—it’s the “Free Bird” for people who are sick of hearing about “Free Bird.” —Garrett Martin

23. The Black Crowes: The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion (1992)

After the commercial success of their solid and straightforward 1990 debut Shake Your Money Maker, the Atlanta hippy throwbacks took a giant leap forward with their second effort, plugging in new and better instrumental elements and writing a batch of songs that built on their Stones of the South bedrock with nimble, cocksure jaunts into psychedelia, blue-eyed soul, and British black-magic riffage. Marc Ford was a huge upgrade on lead guitar, giving the Crowes the true gunslinger they lacked on Money Maker and lifting punchier songs like “Sting Me” and “Hotel Illness” into mini-epics. And new organist Eddie Harsch helped free the band from the confines of bar-band bromides with an agile undercurrent of psych, folk and saloon keys. The Robinson brothers took the opportunity to spread their songwriting way out, juicing the Faces and the Allmans with the forcefulness of the hard-rock ‘80s and arriving at an early career peak. “Remedy” rumbles down three descending chords and “Sometimes Salvation” rides them right back up, lurching all the way to screaming redemption “in the eye of the storm.” The climax comes in the woozy slide-guitar workout “My Morning Song,” with Chris Robinson preening in pure LSD-freak euphoria and the twin guitars of Ford and Rich Robinson leading the band to the edge of collapse and back. The Crowes would never get it this right again. —Matthew Oshinsky

22. Lynyrd Skynyrd: Second Helping (1974)

If this Jacksonville band found its sound (The Rolling Stones relaunched in Florida biker bars) on its debut album, (Pronounced Leh-nerd Skin-nerd), it found its songwriting voice on this sophomore release. On songs such as “Sweet Home Alabama,” “Workin’ for MCA” and “The Needle and the Spoon,” lead singer Ronnie Van Zant was able to dig into the tensions between North and South, musicians and labels, drug highs and drug lows and reveal the humanity of all involved. And with songs such as “The Ballad of Curtis Loew,” he showed a surprisingly tender sympathy. This is where they proved just how much range a Southern rock band could have. —Geoffrey Himes

21. Alejandro Escovedo: Gravity (1992)

The son of Mexican immigrants, Alejandro Escovedo grew up as a surfer and punk-rocker in California, but it wasn’t until he moved to Texas that he was able to put those two halves of his identity together, first with the overlooked roots-rock band The True Believers and then with a solo career that began with this stunning album. With his Mexican background reflected in the violins and lilting melodies of his parents’ homeland and his punk-bohemian side echoed in the spiky electric guitar riffs of the West Coast demimonde, the two sides were bridged by the singer’s spare but evocative lyrics, which distilled conversations on both sides of the border to their aphoristic essence. —Geoffrey Himes

20. The Avett Brothers: Emotionalism (2007)

In the late ’60s, The Band’s earnest roots rock helped topple nonsensical hippie credos like “Don’t trust anyone over 30.” Similarly, The Avett Brothers did their best to combat modern-day hipster detachment and pseudo-coolness with Emotionalism’s simple, poetic story-songs and bittersweet, introspective laments. The album—down to the title itself—was a celebration of unselfconscious passion and a huge step forward musically: The relative sonic polish worked magically in contrast to the Avetts’ jagged edge; they went beyond their core of acoustic guitar, banjo and upright bass (a change foreshadowed by Four Thieves Gone’s “Colorshow”), adding piano, B3, drums, electric guitar and mandolin; the vocals felt more carefully arranged, relying less on energetic screams and shouts and giving the melodies room to breathe; and the influences peeking through were more varied than ever, the music sporadically reminiscent of everything from Help!-era Beatles to Chopin nocturnes. This was the album where the Avetts, long deemed “promising” by critics, began unflinchingly—unguardedly—delivering on that promise.—Steve LaBate

19. Gregg Allman: Laid Back (1973)

You’ll recognize a lot of song titles when you look at the back cover of Gregg Allman’s first solo album. There are rerecorded versions of Allman classics, including a swampy, haunted version of “Midnight Rider,” and an overwrought take on the underrated gem “Please Call Home.” There’s a funereal take on the Carter Family’s adaptation of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” There’s a cover of Jackson Browne’s “These Days” (made famous by Nico) that’s all steel guitar glissando, Allman’s mournful vocals and the warm glow of an electric piano. And then there’s “Queen of Hearts,” which is not the Hank DeVito song that Juice Newton made famous, nor the traditional ballad that Joan Baez popularized, but an epic Allman original that’s both mournful and triumphant at the same time. That basically summarizes the album—don’t expect the guitar-heavy jams of the Allman Brothers, but a sad, contemplative record that sounds like the morning after the parties heard on Eat a Peach and At Fillmore East. —Garrett Martin

18. Elvis Presley: The Sun Sessions (1975)

A persuasive case can be made that this is the best rock ’n’ roll album of all time. It wasn’t the first time someone had blended the Southern ingredients of blues, gospel and country music over a propulsive 4/4 beat into a new music dubbed rock ’n’ roll, but no one ever did it better. While his role models had lamented the inevitable frustrations of this world, Mississippi’s Elvis Presley shrugged off all such worries with a blithe confidence and a thrilling vibrancy of optimism that changed American culture forever. Thirteen of these 16 tracks have neither drums, electric bass nor solid-body guitar, proving rock ’n’ roll wasn’t defined by technology so much as an attitude—and no one had more attitude than Presley. The songs here, recorded in 1954 and 1955, weren’t collected into an album until 1975 in England, but these recordings—made at the same time by the same Southern musicians under the same Southern producer—have a coherence of sound and spirit that few other albums can match. —Geoffrey Himes

17. Steve Earle: Guitar Town (1986)

If Bruce Springsteen had grown up in Texas listening to Lefty Frizzell on the radio in a beat-up pick-up truck, he might have sounded a lot like Steve Earle. Earle has the Boss’s ability to tell blue-collar stories with just the right details and just the right guitar licks, but Earle sets his tales in small Texas towns and gives his riffs a tell-tale twang. Earle, who once played bass for Guy Clark, cut some singles for Epic that went nowhere, but 1986’s Guitar Town was his debut album, and he never topped this country-rock evocation of the forgotten kids too small for a football scholarship, too restless to stay home and too tough to give up. Co-producers Emory Gordy and Tony Brown turned four of them (“Hillbilly Highway,” “Guitar Town,” “Someday,” and “Goodbye’s All We’ve Got Left”) into Top 40 country hits. But at its heart, this is simply the twangier side of Southern rock. —Geoffrey Himes

16. Big Star: #1 Record (1972)

Years after his untimely death at 59, Memphis son Alex Chilton has remained a cult hero. Chilton first rose up to pop stardom as a member of The Box Tops in his teens, then threw that success away to join the chaotic, whiskey-driven rock ’n’ roll scene in his hometown, both as a member of Big Star and as a solo artist and producer. Along with master guitarist and singer-songwriter Chris Bell, Chilton formed Big Star in the early ’70s as a breath-of-fresh-air alternative to the stadium-sized rock that ruled the radio at that time. Rooted in the heart of Memphis, Big Star wrote Beatles-esque arrangements with a Southern twist, releasing a debut album that would later influence R.E.M., Elliott Smith and The Black Crowes, among many others. Though they wouldn’t achieve much commercial success until years later, #1 Record is Big Star’s underdog masterpiece of melody and conviction. The Allman Brothers weren’t the only Southerners kicking up a new storm in 1972. —Loren DiBlasi

15. Jerry Lee Lewis: Jerry Lee Lewis (1958)

Despite a somewhat tame-looking cover, Jerry Lee’s eponymous debut raised the bar for every rowdy, rambunctious, hells-a-poppin’ insurgent that would follow in his footsteps. It offered definitive proof that this particular son of Louisiana had no qualms about turning the tables on the genteel manners and polite reputation credited to those who dwelled below the Mason Dixon Line. Indeed, other than Little Richard, no other piano player came across as such a barroom brawler, and this album not only set the standard, but laid the course for all that would follow. Ironically, Sun Records owner and producer Sam Phillips opted not to include two of Lewis’s biggest hits at the time, “Great Balls of Fire” and “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On,” though with “High School Confidential” and a slew of sometimes curious covers — “Don’t Be Cruel, “Goodnight Irene,” “Jambalaya,” and “When the Saints Go Marching In,” among them — Lewis still managed to etch an indelible impression. —Lee Zimmerman

14. Drive-By Truckers: Decoration Day (2003)

On DBT’s 2001 breakthrough double album Southern Rock Opera, the band traded its alt-country “redneck underground” approach for a Skynyrd-meets-Crazy-Horse vibe. On the more concise follow-up, Decoration Day, the Truckers distilled their new sound from 80 to 100 proof. Start to finish, every cut on this gritty, unapologetic, punk-tinged roots-rock record is a classic, as master storytellers Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley unravel one tragic, chilling small-town Southern yarn after another. With tunes like “Sink Hole” (based on Ray McKinnon’s Oscar-winning short film, The Accountant), the unflinchingly honest rocker “Marry Me,” “My Sweet Annette” (with its jilted title character), the and heart-crushing divorce ballad “Sounds Better in the Song,” the caliber of songwriting went through the roof like a shotgun blast. And that’s without even mentioning the debut of the Truckers’ secret weapon during this period—then-24-year-old singer/guitarist Jason Isbell, whose blistering leads and slide work gave the band a shot in the arm, as did the epic pair of tracks he contributed to the record: father-to-son ballad “Outfit” and the title song, with its bloody Hatfields and McCoys-style family feud. The Truckers have never been more themselves than they were on Decoration Day, and they’ve never been better.—Steve LaBate

13. .38 Special: Wild-Eyed Southern Boys (1981)

Southern Rock had a pop side, too, and 38 Special’s 1981 album marked the beginning of the Jacksonville band’s dominance on that front. It was the first of the band’s albums to sell more than a million copies, and it yielded three singles that charted. Donnie Van Zant (younger brother of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s original frontman, Ronnie Van Zant, and older brother of the man who replaced Ronnie, Johnny Van Zant), Don Barnes and Co. put less emphasis on surging guitars and instead emphasized stick-in-your-head melodies, for which they had a particular knack. Along with the title track, Wild-Eyed Southern Boys includes the FM-radio staples “Hold On Loosely” and “Fantasy Girl,” which will be familiar to anyone who has listened to a rock station at any point in the past 35 years. —Eric R. Danton

12. Bo Diddley: Bo Diddley (1958)

To limit Ellas McDaniel (aka Bo Diddley) to being a blues or R&B artist is to ignore the impact the Mississippi native had on the birth and growth of rock ’n’ roll. He influenced Elvis Presley, of course, but he also toured the UK with an unknown band called The Rolling Stones, who’d get their start playing covers of Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters and Little Richard. Bo Diddley, a compilation of his late ’50s singles, kicked off his most prolific period in 1958—he released 11 LPs on Chess in a six-year period. It laid the groundwork for the new genre of rock ‘n’ roll with his signature Bo Diddley Beat, the syncopated blues rhthym that’s shown up in rock songs ever since (think “Desire” by U2 or “Magic Bus” by The Who). Not a song here is over three minutes long, and they’ve since been covered by everyone from George Thorogood, The Doors and The Jesus and Mary Chain (“Who Do You Love?”) to Captian Beefheart and Ty Segall (“Diddy Wah Diddy”) to The Animals (“Pretty Thing”). —Josh Jackson

11. The Allman Brothers Band: Eat a Peach (1972)

The first Allman Brothers Band album released after guitarist Duane Allman’s death is a sprawling beast that highlights every one of the band’s strengths and serves as a tribute to its fallen brother. Chief among those are Duane’s mastery of the slide guitar and Gregg Allman’s incomparable voice, but Eat a Peach also underscores the band’s multifaceted songwriting proficiency, from the half-hour “Mountain Jam” to the plaintive pop of “Melissa” to the upbeat guitar calisthenics of Dickey Betts’ “Blue Sky.” All in all, this was the Allmans’ finest studio recording. —Garrett Martin

10. The Marshall Tucker Band: The Marshall Tucker Band (1973)

When you think “Southern rock,” the flute probably doesn’t come to mind, but The Marshall Tucker Band, from Spartanburg, S.C., never cared about typical genre standards. Their self-titled debut offers everything you’d expect from Southern rock: strong, harmonized vocals tinged with twang, jangly guitar solos and the delectable fiddle, but they elevate the album with unexpected brass instruments, gospel-esque organ sections and, of course, their commendable flautist, Jerry Eubanks. All together, it’s surprising but downright felicitous. Standout tracks include “Ramblin’” and “Hillbilly Band,” but don’t forget the classic-rock radio mainstay, “Can’t You See.” There’s a reason it’s played several times a day on FM all over the country. —Annie Black

9. Jason Isbell: Southeastern (2013)

The first few years of Jason Isbell’s solo career, late of Drive-By Truckers, were beset with personal problems, including a well-publicized struggle with alcohol abuse, and his first three outings often played like too much of the same thing. But with Southeastern, Isbell broke his hard-luck streak, crafting an album worthy of his considerable talents. Each of the songs is a stunner. “Cover Me Up” is on the one hand a gentle, insistent love song, and on the other a moving testament to personal redemption that never turns a blind eye to past indiscretions. It sets the tone for the remainder of the album, which is given equally to the promise of romance and the ever-looming possibility of suffering, both self-induced and arbitrary. As good as the songs are, Isbell’s singing may be even better. His baritone, always rich, is deepened here by a grittiness that lends Southeastern a real soulful quality. By any reasonable aesthetic criteria, Southeastern is a triumph, among the most potent expressions of Isbell’s songwriting and arranging skills (including his Drive-By Truckers output). —Jerrick Adams

8. ZZ Top: Tres Hombres (1973)

While Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Duane Allman-less Allman Brothers were busy gussying up their Florida boogie with country ballads and jazz inflections, ZZ Top were over in Texas scraping the varnish off and leaving only the essential ingredients. On their third album, the trio more or less perfected the formula that would keep them in beard oil for the next four decades: take the roadhouse rhythms of blues masters John Lee Hooker and Jimmy Reed and play them way faster, tighter and with the gain turned to 10 for the ‘70s hard-rock crowd. The opening riff on “Waitin’ for the Bus” slithers right out of whatever Houston swamp Billy Gibbons, Dusty Hill and Frank Beard were hanging out in before 1973, all humid and sleazy. With the trio in perfect lockstep. Tres Hombres moves forward from there with breakneck momentum: “Beer Drinkers and Hell Raisers” is basically a ‘73 Camaro with a kickass guitar solo in the middle; “Precious and Grace” wriggles along on razor blades; and “La Grange,” the band’s crowning achievement, is a fiendish blues stomp about a Texas whorehouse, stripped back to a skeleton riff with a barking Gibbons vocal and a Southern groove so pure they got sued for it. And won. —Matthew Oshinsky

7. Lucinda Williams: Car Wheels On A Gravel Road (1998)

Up until this album Williams was primarily known for her songwriting, earning a Grammy for Best Country Song with Mary Chapin Carpenter’s crossover hit “Passionate Kisses.” But Car Wheels established Williams as a critically powerful recording artist. In spite of its tumultuous and lengthy history of re-recordings and collaborative changes, every song stands strong. From her steamy, breathy refrain of “Oh, baby” on the opening track “Right In Time” to her emotional tribute to the late Blaze Foley on “Drunken Angel,” the stories in the songs, along with a laconic, southern drawl of rock guitars, serves as the perfect soundtrack to a backroads drive through the South.—Tim Basham

6. Little Richard: Here’s Little Richard (1957)

If there are defining moments of rock ‘n’ roll, track one, side one of Little Richard’s debut album is one of them. “Tutti Frutti” announced its presence with Little Richard’s out-of-control sing-shouting, “A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-wop-bam-boom!). This was the sound of million teenagers realizing that they could have a music all their own, and that it could be played by a flamboyant black man from Macon, Ga. These dozen songs, which also include “Slippin’ and Sliden’,” “Long Tall Sally” and “Rip It Up,” caused fans at Little Richard concerts in the late 1950s to go crazy, climbing bannisters, rushing the stage and, yes, throwing panties on the stage. This was the music your parents feared would corrupt their progeny. In other words, this was rock ’n’ roll, delivered by perhaps its greatest-ever evangelist. —Josh Jackson

5. R.E.M.: Murmur (1983)

You know about the mumbling, the muttering, the indie success story, the simultaneous conquest of college radio and Rolling Stone—and subsequently, the world. But maybe you don’t know how punk never quite married Southern gothic roots to Rickenbacker arpeggios until “Radio Free Europe” and “Sitting Still” made it safe for bands like The dB’s. Maybe in retrospect it’s amazing how “Talk About the Passion” and “Perfect Circle” were such power ballads. And maybe you don’t have to understand a word of “Moral Kiosk,” “Catapult” or “We Walk” to hear how every odd harmony, surf lick and overdubbed billiard ball made perfect sense when coming from the mouth of Michael Stipe. Dark and mossy, it was a re-definition of Southern rock with a distinctly different attitude—taken as much from Tom Petty and Big Star as from the genre’s founding fathers—but there’s no denying that it was very much both Southern and rock. — Dan Weiss

4. Drive-By Truckers: Southern Rock Opera (2001)

Mike Cooley and Patterson Hood both grew up in the Quad Cities (aka the Shoals) of northwest Alabama. Hood’s father, David, was the bassist in the legendary Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section that played on records by Aretha Franklin, The Rolling Stones, the Staple Singers, Paul Simon, Jimmy Cliff and many more. But Patterson rebelled against that legacy by joining a succession of punkish garage-rock bands. He was 21 when he met the 19-year-old Cooley on that circuit. They formed Adam’s House Cat, but they weren’t ready to embrace their roots, Hood told Paste in 2014: “We ran from our Southernness and so many other things that deep down we really were. Cooley was the one with the big Carl Perkins influence, and I was too caught up with the Replacements and R.E.M. to pay attention. The Drive-By Truckers are the band Cooley wanted Adam’s House Cat to be. All these years later, we’ve embraced our Southernness, but at the time that seemed too easy.” Cooley finally started writing songs after he separated from Hood, who had never stopped writing. When Hood played his new songs, he knew they deserved a band behind them and he knew that band had to include Cooley. So he scraped together some money to record a single in Athens and invited his estranged ex-bandmate to play on the session. Things clicked, and soon the Drive-By Truckers were born. They burst onto the national consciousness with 2001’s double-CD concept album, Southern Rock Opera, a song cycle about Lynyrd Skynyrd, Molly Hatchet, Neil Young, Bear Bryant, George Wallace and “the Southern Thing.” The band deserved all the attention it got, for it was a magnificent recording. —Geoffrey Himes

3. Lynyrd Skynyrd: (Pronounced ‘l?h-’nérd ‘skin-’nérd) (1973)

(Pronounced ‘l?h-’nérd ‘skin-’nérd) introduced the world to both the quintessential Southern rock band at the height of its powers and the epic “Free Bird,” empowering decades of slow-witted would-be hecklers with the ability to provoke audible groans from any audience throughout the world. More important, the album features two of the absolute greatest rock songs of all time: “Simple Man” and the elegiac “Tuesday’s Gone,” which made indelible impacts upon both the nascent Southern rock subgenre and classic rock radio playlists nationwide. This one record has those classics and also “Gimme Three Steps,” probably the best song about bargaining for your life with the gun-toting husband of the woman you’re dancing with. And don’t forget “Things Goin’ On,” which proved these long-haired Southern boys had a social conscience and concerns outside partyin’ and drinkin’ and rememberin’ what your momma told you. One of the great debut albums in any genre, Pronounced Leh-nerd Skin-nerd drew a map to the Southern rock glory land behind a three-guitar attack the likes of which we haven’t seen since. —Garrett Martin

2. Johnny Cash: At Folsom Prison (1968)

It’s no exaggeration to say that Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison is his masterwork. Beginning with the 1957 release of his Sun Records debut, Johnny Cash with His Hot and Blue Guitar (which included “Folsom Prison Blues”), he created a new kind of country that encompassed the compassion of traditional folk ballads, the spit and grit of rockabilly, the dangerous edge of blues and the glory of gospel. Cash—as much as Elvis Presley or Chuck Berry—embodied all the thorny contradictions that defined post-War American popular music, from rock ‘n’ roll to hip-hop. Desperate, difficult, politically incorrect lines delivered with a breaking voice behind the clicka-clicka-chug of bass and guitar—“I shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die” (“Folsom Prison Blues”), “I can’t forget the day I shot that bad bitch down” (“Cocaine Blues”)—have echoed across the rock era, from the outlaw country of Johnny Paycheck to the Gothic punk of Nick Cave to the hardcore hip-hop of Tupac Shakur. But so has Cash’s compassion. There’s a direct link from “25 Minutes to Go,” which Cash sings here from the perspective of a convict on death row, to Shakur’s “16 on Death Row,” in which the rapper also assumes the role of a doomed convict: “Dear Mama, they sentenced me to death / Today’s my final day, I’m counting every breath.” It’s that mix of hard reality and soft empathy that brings Cash’s prison audience to its feet, yelling and whistling its collective approval as if the proceedings might turn into a jailhouse riot at any moment. As Rosanne Cash says in one of the DVD extras accompanying the 2008 re-release, “Rebellion never gets old, and there’s just a giant ‘fuck you’ on the whole record to authority in all its forms. And that’s very seductive, no matter what the generation.” —Andy Whitman

1. The Allman Brothers Band: At Fillmore East (1971)

In many ways the quintessential Southern Rock album, At Fillmore East features definitive performances of some of the Allman Brothers’ best-known tunes, including a jumping version of Blind Willie McTell’s “Statesboro Blues,” the painful 23-minute blues of “Whipping Post,” and the groundbreaking “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” the band’s first original instrumental to feature the dueling lead guitars of Duane Allman and Dickey Betts—the greatest lead-guitar tandem in rock history. The album is a document of the group at its very best: Gregg Allman nails the balance between sultry and mournful in his vocals, Betts and Duane play together so intuitively that it seems like they were the brothers, and the double-drummer rhythm section holds the whole thing together with impeccable skill. Recorded over two nights at Bill Graham’s storied New York ballroom, At Fillmore East showcased the band’s preternatural facility for deep blues (T-Bone Walker’s “Stormy Monday”) and progressive jazz improv (the sprawling “Hot’ Lanta”), making them the premiere purveyors of this rapidly ascending strain of Southern-based rock music. Along with The Grateful Dead, whose tripped-out take on traditional American music had made them stars on the West Coast, the Allmans were blazing a trail for every road-tested band whose stock in trade was its live show, not its studio recordings. With just seven songs stretched over 78 minutes, At Fillmore East was a masterclass in all the ways rock music was being adapted and reshaped by a new generation of torch bearers, with the emphasis split between honoring the origins of the music and pushing it forward to heretofore unknown heights of instrumental magic. The album is also historic for its presence as Duane Allman’s farewell: he died in a motorcycle crash in October 1971, three months after its release. Betts would later call At Fillmore East the Allmans’ “pinnacle.” In that case, it’s also the pinnacle of this thing we call Southern rock. —Eric R. Danton