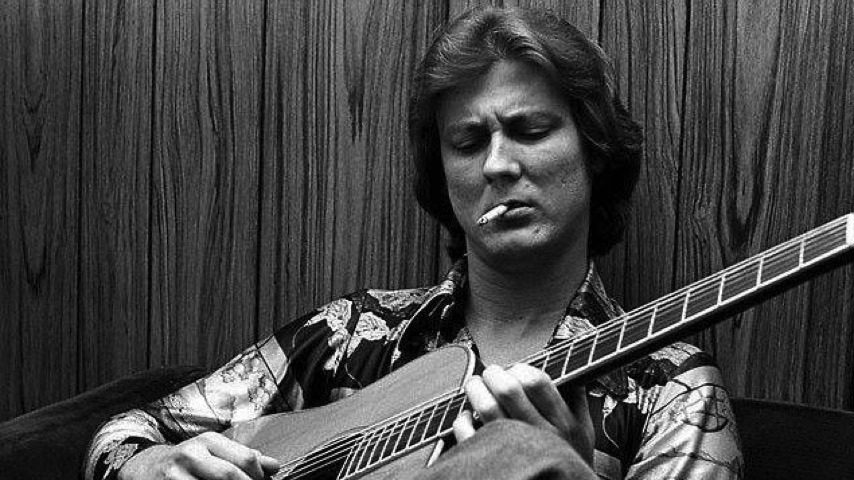

Tony Rice, who died of undisclosed causes Christmas morning at age 69, was more than just a virtuoso bluegrass guitarist. He was someone who changed the very role of the acoustic guitar in American music.

In the days before the widespread use of microphones and amplifiers, the acoustic guitar was almost always a rhythm instrument. When it tried to play single notes, it couldn’t compete with the volume of the fiddle and banjo. Even when gut strings were replaced by steel strings, even when players used picks instead of fingers, the instrument was just too quiet to be heard. Only when it strummed out chords could it make its presence felt.

North Carolina’s Doc Watson, the Louis Armstrong of American guitar, solved this problem by playing solo or in duos and trio with another guitarist and/or bassist. No longer drowned out by the fiddle and banjo, Watson demonstrated the amazing things that his hollow-box instrument could do. His breakthrough was built upon by California’s Clarence White, who used a microphone to make himself heard in the Kentucky Colonels. But White switched from acoustic to electric guitar to join the Byrds and was killed by a drunk driver at age 29.

It was left to Rice to consolidate the innovations of Watson and White and extend them into new territory. He pioneered the acoustic guitar as a soloing instrument in string bands—and then he pioneered the use of jazz harmonies and rhythms in those bands.

Tony Rice had only been eight in 1959 when he first met Clarence White. White was only 15 at the time, but he was already playing guitar with a rhythmic forcefulness and a harmonic imagination that Rice had never heard before, not even on record. The younger boy was soon following his older hero everywhere he went, staring at his hands and memorizing every note in hopes that he too could someday play the guitar as something more than a background rhythm instrument.

“Clarence was an amazing player even at that age,” Rice told me in 2002. “He was playing mostly rhythm, but he was doing something magical that was different from what Lester Flatt and Jimmy Martin were doing. And when his older brother Roland got drafted into the army in 1960 or ’61, the band was left with no one to play leads. Clarence figured out real quick that he could play those mandolin leads on the guitar. At first he copied Roland’s parts, but he was soon inventing his own lines.”

“About that same time, I heard Doc Watson, who was playing leads on acoustic guitar much like Clarence was. They were different because Doc came out of old-time mountain music, while Clarence came strictly out of a bluegrass mode. But they were both brilliant; I can’t put into words how special it was to hear Doc live or on album in those early days. What people don’t realize is how much Clarence influenced Doc; they had a lot of mutual respect for each other.”

White proved that the acoustic guitar could solo on bluegrass changes with all the verve and invention of a mandolinist like Bill Monroe, a fiddler like Paul Warren or a banjoist like Earl Scruggs. If it could handle those tunes, why couldn’t it handle jazz changes like France’s Django Reinhardt or Oklahoma’s Charlie Christian?

“Clarence never gave me lessons or anything like that,” Rice told me; “we were just two kids hanging out together. But I would try to do everything he did, and when I couldn’t I’d invent something of my own. When word got out how good Clarence was, everyone wanted to play with him. He started hanging out with James Burton [Elvis Presley’s guitarist] and listening to Django Reinhardt. Just as I couldn’t match Clarence, Clarence couldn’t match Django but in trying he came up with something more daring than he’d done before.

In 1970 the 19-year-old Tony Rice replaced Dan Crary in the Bluegrass Alliance, a group that contained Sam Bush, Courtney Johnson and Harry “Ebo Walker” Shelor—three-fourths of the future New Grass Revival. In 1971, though, Rice joined his brother Larry in J.D. Crowe & the New South. By 1975, the band included Crowe, Tony Rice, Ricky Skaggs, Jerry Douglas and Bobby Slone, and that year’s album, J.D. Crowe & the New South, is still considered one of the top bluegrass albums of all time. Here, for the first time, was a traditional bluegrass line-up where the guitarist was taking solos that held their own with those of the banjo, mandolin and dobro. But this only whetted Rice’s appetite for more challenges. Later that same year, Rice joined banjoist Bill Keith—who had just left Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys—to make a more adventurous kind of string-band album. The new band’s mandolinist was a young, frizzy-haired New Yorker, David Grisman.

“Grisman brought along this tape he’d made with [fiddler] Richard Greene and [guitarist] John Carlini,” Rice said in 2002, “and I had never heard anything like it. Coming out of these bluegrass instruments was a form of modern string-band jazz. The chord changes were unusual and the solos were wild, but still everything was pleasant to the eardrum. I remember thinking, ‘Boy, it would be an honor to someday be a part of that.’ Before too long I was.”

“I had the bluegrass background Grisman was looking for, but I had my work cut out for me. My only knowledge of modern jazz was listening to it and loving it; I had no idea how to play it on guitar. Carlini, who became a good friend, tutored me and I had to learn music theory for the first time. I had first heard jazz when I was a sophomore in high school. My girlfriend had an eight-track tape player in her car, and one day when she turned the car on, Dave Brubeck’s ‘Take Five’ started playing. It grabbed me the same way Flatt & Scruggs had back in 1955.”

After four years with the David Grisman Quintet, the guitarist formed the Tony Rice Unit, an instrumental ensemble that pursued Grisman-like string-band jazz but with Rice’s compositions and a bluegrass-flavored sound. At the same time, however, he made solo albums that showcased his handsome voice.

Singing songs by Bill Monroe, Bob Dylan and Gordon Lightfoot, Rice expanded his audience considerably. But when his voice gave out at the 1993 Gettysburg Bluegrass Festival, he stopped singing for good. The diagnosis was dysphonia, a cramping of the throat that prevents singing and gives even the speaking voice a perennial trace of hoarseness. Many musicians would have been devastated by such a setback, but Rice insists that he shrugged it off and returned to his first love, the guitar.

“I don’t worry about it as much as people think,” he said. “The guitar was always the main thing for me. I spent four years with David Grisman where I didn’t sing at all. I got so far into that music, in fact, that I didn’t care if I ever sang again. As I was losing my voice, I was getting more interested in the guitar again; I was getting back to where I was during the Grisman years.”

For the rest of us, though, it’s hard to forget the sound of Rice’s burnished baritone as it delivered contemporary folk songs with conversational ease, as on the 1996 Rounder collection, Tony Rice Sings Gordon Lightfoot. Or the thrill of hearing his voice rise high and lonesome on the classic 1975 album, J.D. Crowe & the New South, or on any of the Bluegrass Album Band projects that Rice has headed up.

“But that was the whole problem,” Rice points out. “My voice gave out from all the abuse of trying to sing too high for too long. Because I was so dedicated to that high, lonesome sound, I was singing out of my range for all those years. I was trying to get my vocal mechanism to do something it wasn’t designed to do. It was a gradual thing over the years; I first noticed something was amiss way back when I was with Crowe.”

To fill the role of his missing voice, Rice began tour as a duo with Peter Rowan, a former member of Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys and of Jerry Garcia’s Old and In the Way. Freed from his former vocal duties, Rice was able to further develop his guitar innovations.

“If I do a gig with Peter,” he reflected in 2002, “and I’ve been listening to some small-combo jazz CDs, I become conscious of an attempt to emulate their approach, even if I’m not playing the same tunes. I get more input and motivation from listening than most musicians do. I listen to the Marsalis brothers, Pat Metheny and Eric Dolphy. I’m a John Coltrane fanatic, but on the opposite end of the spectrum, I’m also a Jascha Heifetz junkie. And some days I’m in the mood to hear some Flatt & Scruggs from 1952.”

As a baby-boomer in Southern California in the early ’60s, Rice was in the right place at the right time to grab hold of the tectonic changes in the use of an acoustic guitar. His parents had grown up in North Carolina, so their sons were rooted into the bluegrass and old-time string bands of Appalachia. But the sons were also plugged into the exploding pop culture of L.A., where folk music, rock ’n’ roll, jazz and classical music were equally available. Many young guitarists were bombarded by this smorgasbord of stimuli, but only Rice was able to translate it into unprecedented guitar playing.

“Because I grew up in Los Angeles, where bluegrass wasn’t an accepted form, I became a very different kind of bluegrass guitarist than I might have back East,” Tony he told me in 2001. “Because bluegrass was a smaller part of the scene, the folk boom was much more important, and that made me a different kind of singer and picker. And because I met Clarence White at an early age in California, I became a lead guitarist rather than the usual rhythm guitarist and singer you might find in a traditional bluegrass band.”