It’s a safe wager that no scatologically titled album ever cast a longer shadow than Green Day’s Dookie. The Bay Area trio’s 1994 major-label debut stumbled upon meteoric success in the wake of Kurt Cobain’s death and the impending decline of grunge, permeating the alt-rock airwaves with a pungent, skunky cloud of pop melodicism mixed with a punk edge and slacker snottiness. Three decades later, we recognize the significance of Dookie and the inextricable role that relatable, straightjacket singles like “Basket Case,” “Longview,” and “When I Come Around” played in both the evolution of pop-punk and the landscape of nineties alternative rock. At the time, though, as Billie Joe Armstrong, Mike Dirnt, and Tré Cool set out to make the record that would become Insomniac, that auspicious future must’ve felt anything but certain. Facing the pressures of sudden superstardom, burned out from touring and addiction, and wounded by accusations of selling out, Green Day responded with an angry, bleak, and urgent collection that suggested all might not be well in the “smoked-out, boring rooms” scattered across Dookie.

For all of Insomniac’s pissed-off aggression, the album actually snapshots Green Day going into a strategic retreat rather than an all-out offensive aimed at their suffocating circumstances. Success had largely sapped the fun out of playing shows, and the band found themselves shunned as punk pariahs among the Berkeley scene that had nurtured them since their Sweet Children beginnings. Disenchanted with the hysteria of what Armstrong once sarcastically dubbed “winning the lottery,” the trio turned to their next batch of songs to try and gain back some sanity as the outside world spiraled further out of control. Dirnt has described Insomniac as a collection of individual feelings that the band could grapple with, process, and move on from. While Armstrong bashfully insisted that writing the album wasn’t like “self-therapy,” thinking of Insomniac in those terms helps explain why this half-hour, breakneck purge of a record lands like such a striking departure from its feces-flinging predecessor. After Dookie’s lighthearted, juvenile blast through the timeless bullshit of adolescence, Insomniac finds the boys of Green Day (now, gasp, family men) peeling themselves off that velcro couch in their parents’ basements and dealing with problems threatening to linger longer than a cloud of pot smoke.

Lead track “Armatage Shanks,” which takes its name from a British toilet manufacturer, wastes no time in dropping fans directly into Green Day’s troubled headspace. Tee’d up by Cool’s opening salvo, Armstrong informs listeners that his outlook has matured (read: worsened) from the innocuous, childish nihilism of Dookie (“I declare I don’t care no more”) to a more practical cynicism (“I must insist on being a pessimist”) in the aftermath of the band’s stupefying success. Confusion, rejection, and alienation are the sentiments of these cornered artists. Like the majority of the album, emotional urgency begets high-octane velocity, the foot only coming off the gas to let Cool’s rapid fills or Dirnt’s vibrant basslines surface like fresh graffiti on the blank spaces of a thoroughly tagged wall. It’s maybe not such a wonder that their next album, Nimrod, would get slapped with the “indulgent” label after Insomniac’s songs refuse to loiter even an extra second or two.

As Insomniac makes clear, Armstrong and company rarely need more than a couple minutes to flex their chops. Macabre humor lands as the deadbeat heir in “Brat” questions if boredom will be the undoing of his financial scheme to wait out his aging parents. “Well, I am just a mutt, and nowhere is my home,” Armstrong introduces himself on “No Pride,” reminding us why he’s still our poet laureate of self-deprecation, as he negotiates a land where “dignity’s a landmine,” all hope has gone missing, and “values … turn to shit.” On famously mislabeled second single “Stuck with Me,” a deft lyrical tweak makes us quickly realize that the song’s protagonist isn’t only in danger of being outclassed (“I’m just alright”) but cast out altogether (“I know I’m not alright”). And that’s the grave difference between Dookie and Insomniac. As the latter plays out and the evidence piles higher, we get a whiff of peril that didn’t exist in the former. There’s clearly a ledge ahead, and listeners can’t be sure if these songs are the band slamming on the brakes or lead-footing the accelerator.

Armstrong’s knack for melody and the band’s natural punch can at times belie more serious issues addressed in Green Day songs. However, that’s not remotely the case with Insomniac’s most memorable singles. From its bulldozing riff to its final titular belch, “Geek Stink Breath” gains rotting traction in our brains and won’t vacate. And while, yes, we can take time to marvel that Armstrong manages to rhyme “methamphetamine” with “blowing off steam,” we’re forever disturbed by his decaying, scabby depiction of meth use. It’s a grinding gear that we hadn’t heard from Green Day before as well as a scary confession regarding where the band might be turning to for succor. Likewise, “Brain Stew” sounds a nightmarish, sleep-deprived siren with its crunching intervals, graphic symptoms, and Armstrong’s brutal rundown of the meth mind and his losing battle with insomnia. While Dookie captures a certain misplaced slacker romanticism about smoking up on a couch in a hazy basement, Insomniac comes clean about both the temporary pleasures and compounding consequences of getting “fucked up and spun out” to cope with mounting problems.

It’s also the grim heft of those singles, which sound like nothing else on Insomniac, that partly prevents us from dismissing other songs as mere musical tantrums. Some argue that the explosive “Jaded” mimics the euphoria of re-dosing after coming down from meth. Even if not the case, older fans might still recall how cheapened “Brain Stew” felt if radio stations didn’t honor the band’s intentions of letting “Jaded” rush in after it. “Bab’s Uvula Who?,” named after an old Chevy Chase SNL sketch, thrashes about as Armstrong spits out and dices a long laundry list of his maladaptive behaviors in an anxious rant about his penchant for mistakes. It’s an internal tension made tangible as the song speeds up and we can hear him getting more and more “wound up” as the track does. Similarly, we can imagine ourselves in the throes of one of Dirnt’s anxiety attacks as the skittish “Panic Song” erupts into a desperate desire to escape the chaos inside. If most of Insomniac’s songs are about pinning down a troubling feeling, then it’s remarkable how often Green Day manage to suck us right into their hellish headspace.

Contrarily, some of the record’s most accessible songs come when Green Day are able to step back from the mania pumping through their minds, nerves, and veins. “86” wears the pain of betrayal on its sleeve as Armstrong takes on the role of gatekeeper at 924 Gilman Street, bluntly telling the orphaned band that they are no longer welcome at the venue they once called home. It’s a ban that would take more than a decade to lift, and the depth of the hurt comes across in Armstrong’s cold, point-blank vocal. On “Westbound Sign,” the singer thoughtfully steps out of his preferred first-person sneakers to consider how the band’s fame has affected those around them. Here, he addresses the decision his wife had to make when packing up her things and moving to California with him, leaving behind all she knew with no guarantees of happiness. Dirnt’s animated bassline helps turn the tables on breakup song “Stuart and the Ave.” as Armstrong delivers arguably the most self-deprecating rejection in history: “I may be dumb, but I’m not stupid enough to stay with you.” It’s a far cry from an early Green Day that would’ve traded their last joint just for the courage to chat up a girl.

Tucked away, almost hidden, at the end of Insomniac paces “Walking Contradiction,” the record’s last single and maybe the greatest insight into how Armstrong generally felt at the time. He’s often talked about how at odds he felt with Green Day’s fame following Dookie’s breakthrough success. On one hand, he believed in the band’s abilities and his own worth as a songwriter; however, rejection from his hometown scene and the inevitability of disappointing people when you’re suddenly composing songs for millions weighed on that confidence. “A victim of a catch-22,” he dubs himself on “Walking Contradiction,” which propels itself on his gift for phrasing as much as a leftover riff from Dookie. You might even call it Armstrong’s “Song of Myself,” understanding that when the “shit’s so deep you can’t run away,” you can’t help but contradict yourself or, as Whitman put it, “contain multitudes” in order to wade through.

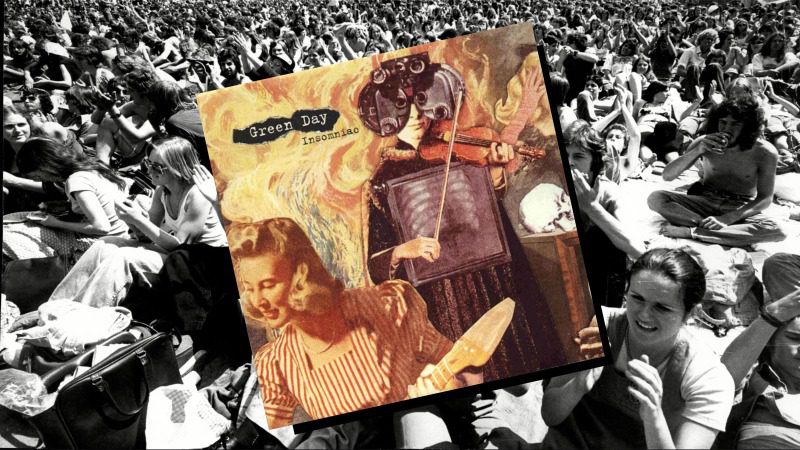

Only in the shade of a global juggernaut like Dookie could Insomniac be considered a bust. The sophomore effort for Reprise Records sold more than two million copies on its way to #2 on the charts, and the album’s dadaist collage artwork, as well as its unnerving music videos, have become iconic visuals in their own right. In retrospect, we can appreciate that Armstrong considers it Green Day’s “most honest” record—the album the band needed to make as opposed to the one fans wanted. It’s that same self-determining, middle-finger ethos that soon led to the kitchen-sink exploits of Nimrod and later fueled grandiose punk-rock opera American Idiot, the band reinventing themselves at a stage in their career where most acts have sunk into relative complacency. In simpler terms, though, Insomniac remains a testament to the power of a fistful of catchy, pissed-off songs to help us outlast the bullshit that comes with, as Armstrong might sarcastically say, having the time of your life.