1984 was a banner year for music in the eighties, and 1985 somehow topped it. Of course, the midway point of the decade didn’t have a Like a Virgin or Purple Rain, but it didn’t need titles like those. Hip-hop was taking off and post-punk was turning into synth-pop; poets and crooners were putting out career-best efforts while now-fundamental bands were still finding their voices. I like 1985 because of that, because it gave us a Kate Bush masterpiece that isn’t even Kate Bush’s best album and let us into the wild, strange, and perfect worlds of Prefab Sprout, Dead Can Dance, and the Jesus and Mary Chain. After a remarkable year of music for American artists in ’84, ’85 switched things up and spotlit new and old talent across the pond.

For this list, I’ve elected to highlight just 30 albums, as opposed to the 50 that made it onto the 1975 ranking earlier this year. I’m trying to be more selective about this type of thing. And, after doing that big 21st-century list a few weeks ago, I needed a much smaller portion. (When we do the 1995 next month, expect the same number of entries, maybe less!) As always, no live albums or EPs have been included, for the sake of fairness (my apologies to Sam Cooke and Iron Maiden). Here is Paste‘s official list of the 30 greatest albums of 1985. Let me know in the comments which release from this year is your favorite, and don’t hesitate to tell me which of my omissions is the greatest sin.

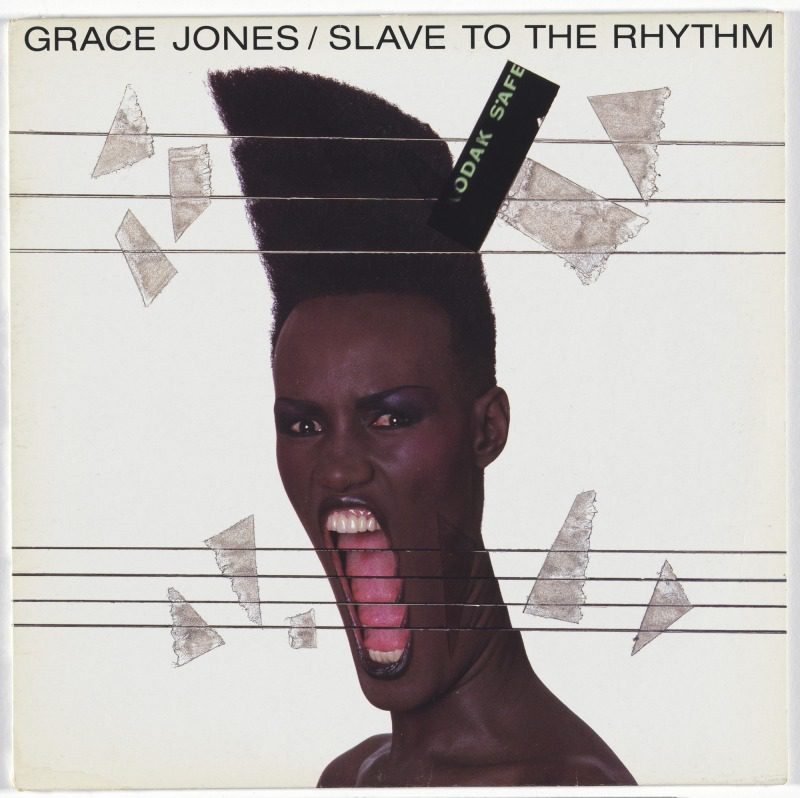

After making her acting debut in Conan the Destroyer a year earlier, Grace Jones returned to the Power Station in 1985 to record Slave to the Rhythm. The LP would become one of Jones’ most successful, cracking the Billboard 200 and spawning one of the most important R&B singles of the eighties, “Slave to the Rhythm,” which went to number-one on the US Dance Club Songs chart and cracked the Top 5 on pop charts in five other countries. Slave to the Rhythm marked Jones’ first batch of new songs in three years, and her return to the studio came with a concept (an album of several interpretations of one song) and vibrant textures of funk, go-go beats, and R&B music. The eight tracks contain excerpts from interviews with Jones about her life, which were conducted by Paul Morley and Paul Cooke, and Ian McShane recites Jean-Paul Goude’s biography in other passages. With Trevor Horn behind the boards, Slave to the Rhythm exists in a pantheon of other story-forward albums he’d previously worked on, like Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s Welcome to the Pleasuredome and Yes’s 90125. It’s a real treat to immerse yourself in such an expansiveness, where pop craft meets memoir. —Matt Mitchell

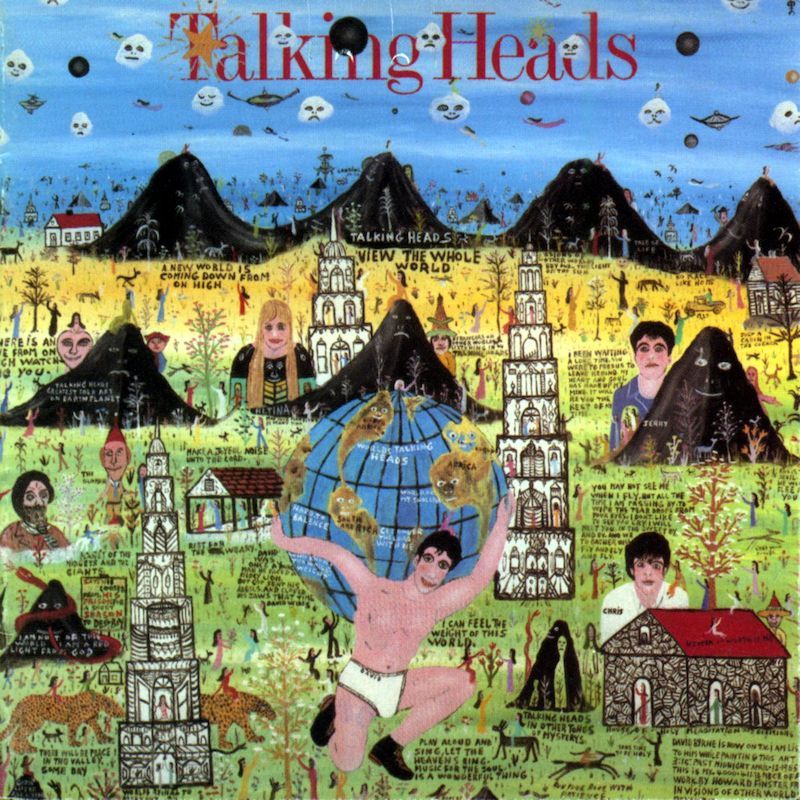

29. Talking Heads: Little Creatures

Talking Heads’ sixth-best album is still better than most bands’ masterpieces. The LP, which arrived at the dawn of summer forty years ago, ushered in the Heads’ final chapter as an active band, in the aftermath of Speaking in Tongues and Stop Making Sense. David Byrne’s fascination with Americana began to boil here, in a potent cocktail of steel guitar, washboard, and accordion, along with ample percussion and backing vocalists. When I think about songs that should have been number-one hits and certainly should have been, “As It Was” is a dependable first-round draft pick. And few moments in the Talking Heads’ songs have been as pastoral as “Road the Nowhere.” It’s too bad Little Creatures was the first glimpse of the end for Byrne, Chris Frantz, Jerry Harrison, and Tina Weymouth. Lucky for us, their near-finish still sounds great. —Matt Mitchell

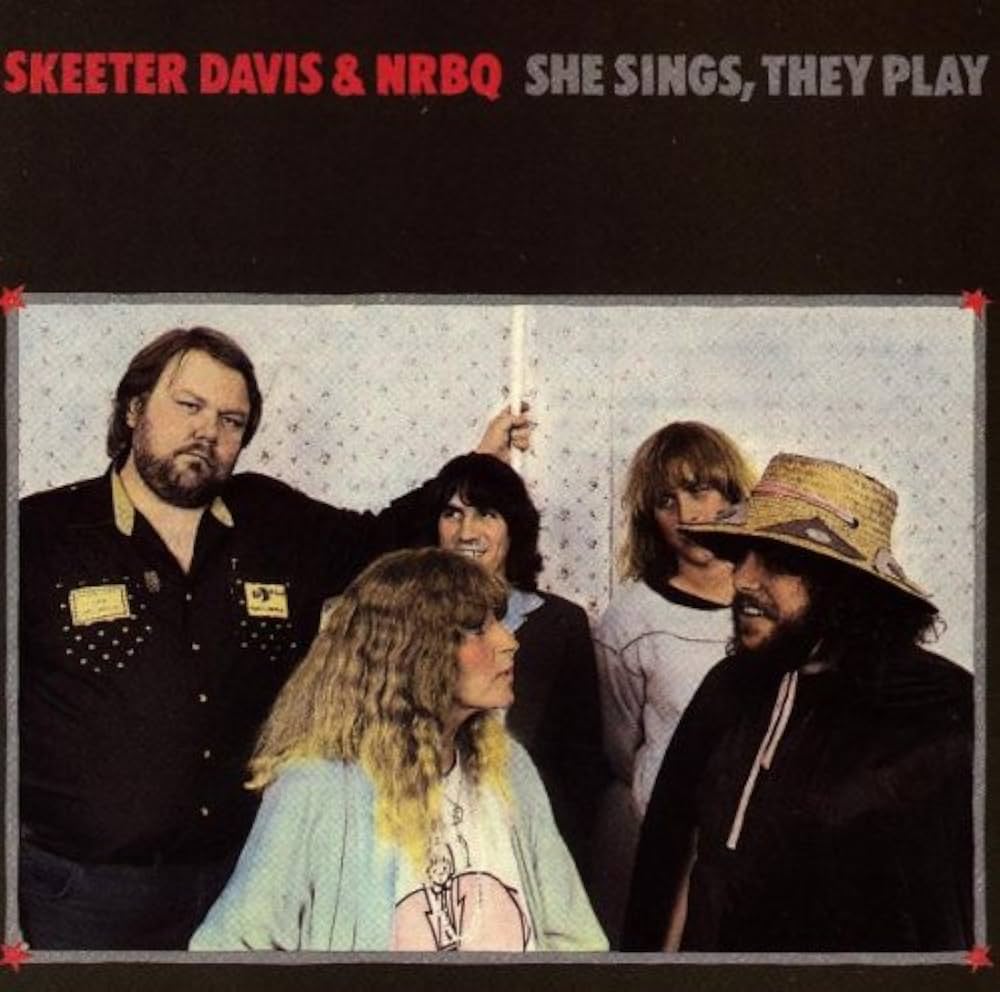

28. Skeeter Davis & NRBQ: She Sings, They Play

The lineage of Skeeter Davis is vast. After singing with her sisters in the Davis Singers group, she went solo and charted a couple-dozen singles in less than twenty years. She inevitably joined with a band called Pandora’s Box, later renamed NRBQ, and crafted the most eclectic record of her career, She Sings, They Play. They play “Someday My Prince Will Come” in 4/4 time, and “I Want You Bad” and “I Gotta Know” are certified rockers. I mean, this album sounds massive even when it’s gentle. “Things to You” is one of my favorite songs ever, and nobody in my life even knows what it is. Davis’ performance on the stilling “Ain’t Nice to Talk Like That” warms my unpolished heart. She Sings, They Play is a record I never tire of. I don’t think Davis ever sounded better than when she was in the company of NRBQ, her voice always entrancing, most especially on “Temporarily Out of Order.” I don’t really believe in wanting to hear an album for the first time again, but if I did, I think She Sings, They Play might be near the top of my list. —Matt Mitchell

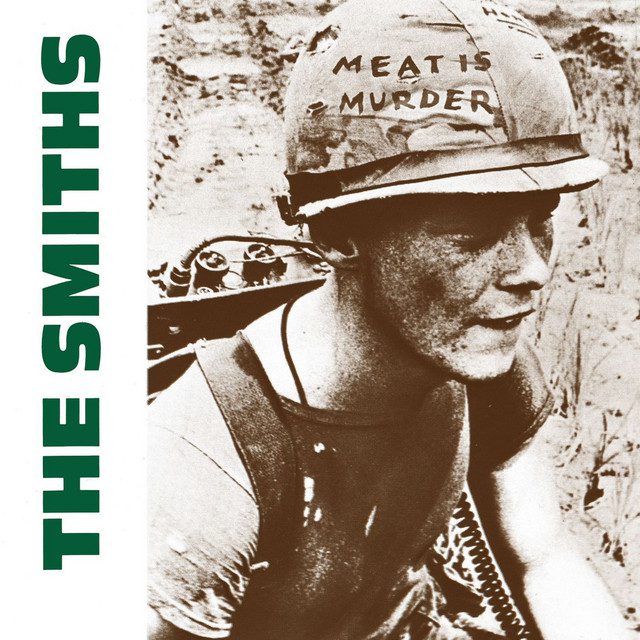

Meat Is Murder, the follow-up to the Smiths’ self-titled debut LP, arrived smack in the middle of the 1980s, on February 11, 1985, which is a fact I’ve always found surprising. The Smiths never sounded to me like an eighties band; they seemed, to the contrary, older, and entirely antithetical to the synthesizers and glamorous sense of fun I tend to associate with the decade’s music. They always seemed so serious, which, given how funny Morrissey’s writing can be at times, probably isn’t fair, but, with an album title as bleak as Meat Is Murder, it’s an understandable interpretation. Morrissey is more adept at inducing empathy for other people. Where his depiction of the violence done to animals is too great and broad to truly land with me, the ordinary human-on-human violence he sings of throughout the album hits closer to home. Meat Is Murder’s first song—a hard, cool slap to the face, if ever an album opener could be—is “The Headmaster Ritual,” an almost Dickensian tale of cruel, military-like teachers in bleak schools subjecting their students to thwacks on knees, knees to groins, elbows to faces. The humdrum violence Morrissey sings of was a very real part of schooling once upon a time, but not one that I, a soft, delicate millennial, ever experienced. Yet the Smiths have this wonderful ability to, through both the music and the poetry of Morrissey’s words, provoke the pleasure and pain of one’s memories, even if the content of the song and the listener’s memories don’t quite align. Their music taps into a well inside us which shouldn’t necessarily even be there. —Tiernan Cannon

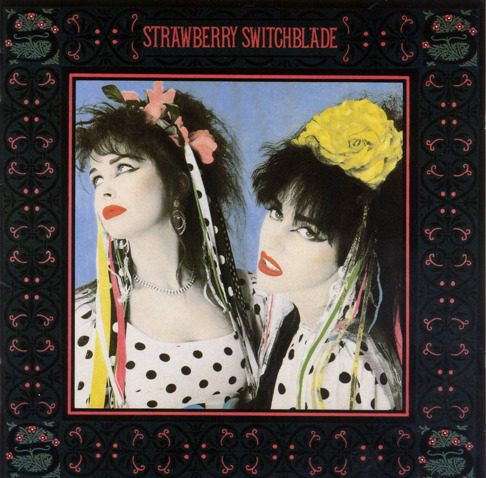

What two polka dot dress-clad women in bows made true in 1985 is simple: Strawberry Switchblade is one of the greatest New Wave debuts (and records, in general) of all time. They were on the cover of Smash Hits once upon a time, but their first LP was far more rebellious in the eyes of what kind of pop music was appealing. Their cover of Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” completely reinvented the pop classic before Whitney Houston ever got her hands on it; “Go Away” and “10 James Orr Street” were such desolate synth-pop songs that even Suicide might have been a bit bummed out listening to them. “Let Her Go,” however, sounds bright enough for ecstasy and swells into a metallic guitar solo. That “And I know I would let go” chorus seemingly unspools the melancholy, if only for a moment. “Little River” has an opening drum beat akin to something that, on a molecular level, might make sense in Footloose—only to stretch out into something far more in line with the stuff New Order was making right after transitioning out of Joy Division. The 40-year influence of Strawberry Switchblade is much more embedded far beneath the surface of modern pop music than it is some generational, formidable imprint you can grab hold of. It’s alive in the Weather Station’s nimble, watercolored falsetto or in the post-modern synth starbursts of someone like Cate Le Bon. It lives on the fringes of rock and roll and electronica, exuding the danceable mystique of Yaz’s “Too Pieces” (“Another Day”) and the pensive, dubby transcendence of Bauhaus’ “She’s in Parties” (“Let Her Go”). Strawberry Switchblade had a penchant for making misery sound syrupy. The palette of Strawberry Switchblade is as colorful as the wardrobe McDowall and Bryson donned on-stage—a style that was no doubt influential in J-pop and, eventually, K-pop circles in Asia, where their biggest fan base was. By the time the 1980s were over, songs like “Go Away” and “Being Cold” made them peers with Julee Cruise, while “Secrets” and “Deep Water” kept them in conversation with the Pet Shop Boys. But, from “Since Yesterday” all the way through “Being Cold”—and into tracks like “Ecstasy (Apple of My Eye)” and “Black Taxi,” which were only available on the Japanese release of the album—the nocturnal moods of Strawberry Switchblade’s work collided head-on with crack-shot jolts of golden pop standards, even if the charts didn’t reflect it. —Matt Mitchell

25. Mantronix: The Album

Rap music forty years ago was a lot of Raising Hell and Licensed to Ill. It was LL Cool J and ghettoblasters. But Mantronix’s use of a Roland TR-808 was among rap’s first watershed moments. Maybe you didn’t know that Ryuichi Sakamoto’s imprint on MC Tee and Kurtis Mantronik would forever change how samplers are utilized, but “Riot in Lagos” and “Needle to the Groove” remain tethered to one another even in 2025. Mantronix’s debut, The Album, is a fundamental record that’s since inspired the likes of Kanye, Venetian Snares, Pete Rock, and, hell, even Beck, who sampled “Needle to the Groove” on “Where It’s At.” Rap, IDM, sampledelia, bounce, and rock music owe something to Mantronix and songs like “Hardcore Hip-Hop” and “Fresh Is the Word.” Without The Album, the golden age of rap and electro looks and sounds a lot different. —Matt Mitchell

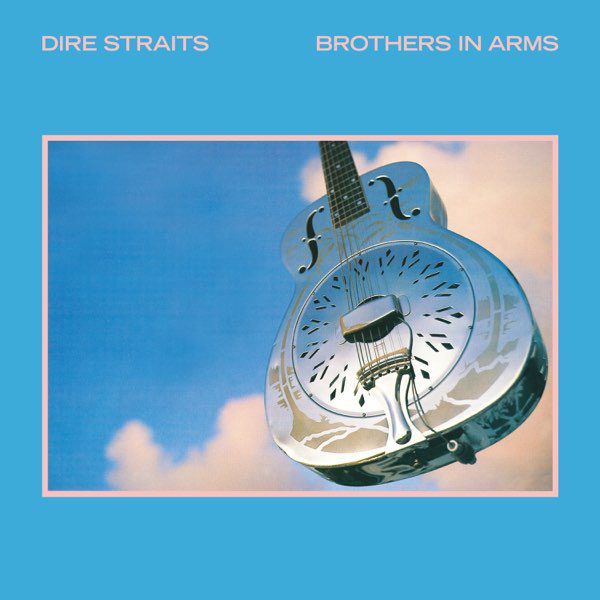

The inaugural album to go platinum ten times in the United Kingdom wasn’t The Dark Side of the Moon, or Thriller, or a Queen greatest hits compilation. It was Brothers in Arms, an LP so beloved it sold well in CD format too, becoming the first title to move a million copies. “Money for Nothing” was a blockbuster song—thanks to that avalanche riff from Mark Knopfler, which he achieved by running a Les Paul through a wah-wah pedal. The moves were over-processed and alien, unlike anything he’d done on-record prior. And, compared to Knopfler’s fretboard-scaling in “Sultans of Swing,” “Money for Nothing” is one of the most recognizable “star-making” singles I’ve ever listened to. But Brothers in Arms isn’t just “Money for Nothing.” It’s “So Far Away” and “Walk of Life” and “Why Worry.” It’s a stadium-filler, but with the jazz-rock flourishes Knopfler had executed on Love Over Gold three years prior. “Why Worry” could have been neatly tucked into the Infidels tracklist, but Knopfler’s vocals are far more plaintive and intimate than Dylan’s. The moody, night-dappled “Your Latest Trick” is Dire Straits nearly embracing the synth-pop music that tilted the mainstream and encroached upon their magnum opus. “Walk of Life” was an outlier—almost too upbeat for its own good, arena-sized and giddy yet so full-throttled in optimism that some say Johnny’s still singing oldies. And “Ride Across the River” may be titled like a Springsteen song, but its medleys of synthesized pan flute, mariachi trumpet, and reggae percussion, contrasted by Knopfler’s steam-rolling solo, are perpendicular to the grain, lending to the song a deep eclecticism. —Matt Mitchell

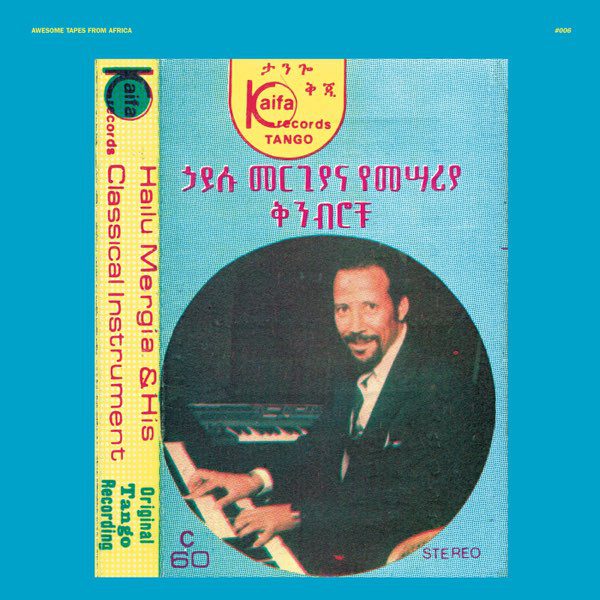

23. Hailu Mergia: Hailu Mergia & His Classical Instrument

A lot of people wouldn’t know about this album had Awesome Tapes From Africa founder Brian Shimkovitz not discovered a copy of it in Ethiopia twelve years ago. I’m thankful for that, because it turned me on to Hailu Mergia’s oneness, sending me down a rabbit hole of Ethiopian jazz that’s totally transformed my taste. It all comes back to this record, which Mergia recorded forty years ago after the Walias Band split. Mergia had already moved to the United States by then and was studying music at Howard University. There, he found an accordion and started taping himself playing it, his synthesizers and Rhodes Piano, and a drum machine. Those recordings turned into His Classical Instrument, a phenomenal second-act after Wede Harer Guzo. The songs—“Amrew Demkew,” “Sewnetuwa,” “Anchin Alay Alegn”—are more psychedelic than anything Mergia had done previously. He fashions the accordion into this strange vessel for odd ideas and a historical yet hypnotic kind of songwriting. At times spooky and at times comforting, His Classical Instrument is a pinnacle for Ethiopian jazz music. —Matt Mitchell

22. Skinny Puppy: Bites

Truly a bonkers album, Bites introduced the world to the Vancouver electro-industrial duo Skinny Puppy in 1985. I don’t know where Nivek Ogre and cEvin Key spawned from, but Bites is one of those projects that picks you apart while it’s flooring your senses. With clean production and fascinating, filmic samples—scavenged from films like Marathon Man, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Tenant, and The Legend of Hell House—scattered across forty minutes of blood-curdling, metallic hemorrhaging, Skinny Puppy strips electronic music down to its ugliest, most terrifying center on songs like “Blood on the Wall” and “Assimilate,” while “Last Call” and “Film” are gentler, sparkly synth-pop ideas. Bites is purposeful in its contrasts and masterfully executed. —Matt Mitchell

21. Beat Happening: Beat Happening

I can see forty years of ideas on Beat Happening, the Washington band’s eponymous debut. It’s lo-fi jangle pop sounds like they were recorded on the cheapest equipment Calvin Johnson, Heather Lewis, and Bret Lunsford could find. Made all over Olympia—13th Precinct, the Firehouse, Yoyo, Martin Apartments, and “Recital hall”—Beat Happening is this radical, campy batch of ideas that have become omnipresent in contemporary indie-pop cosms. The sparse instrumentation, Johnson’s deadpan singing, and a combination of simplistic charm and punky attitude all lend to Beat Happening’s unconventional, strange expression. “What’s Important,” “Don’t Mix the Colors,” and “Run Down the Stairs” are bite-sized mysteries that rummage in a lullaby realm on the margins of pop music, next to the work of the Velvet Underground, Television Personalities, and the Shaggs. Produced by the Wipers’ Greg Sage, there isn’t an album on this list that’s more relevant than Beat Happening. Ian MacKaye dug it, and it left an imprint on both Ben Gibbard and Phil Elverum. Hell, even a band like Being Dead’s flame came from Beat Happening’s torch. Whimsy like this ought to come by the bale. —Matt Mitchell

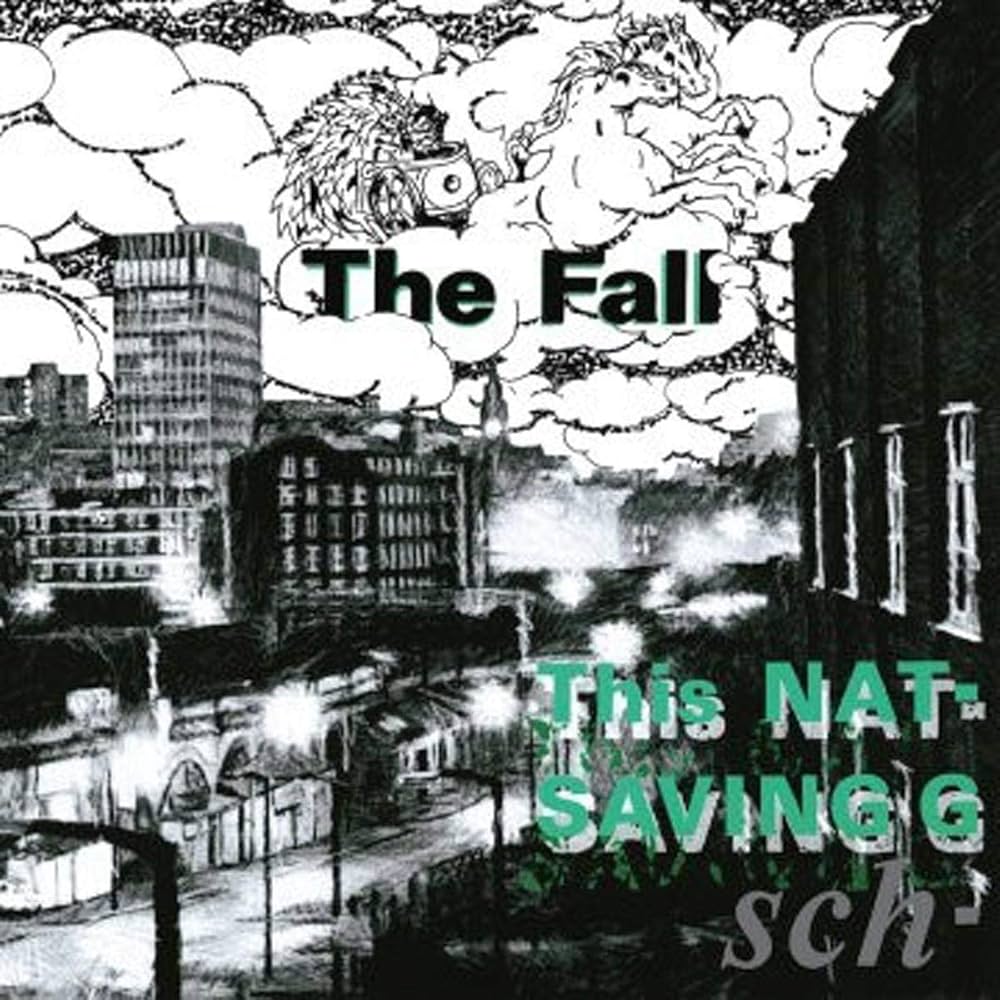

20. The Fall: This Nation’s Saving Grace

Perverted by Language, The Wonder and Frightening World Off…, and This Nation’s Saving Grace—now that’s a trio of records, released by the Fall between 1983-85. It’s a snapshot of a great band operating at an unrivaled level, the latter being, for my money, one of the best post-punk projects of the eighties, thanks to John Leckie’s production and some of the sharpest guitar hooks I’ve ever heard. Seriously, Brix Smith’s riff on “Barmy” still rattles in my head. Coupled with Steve Hanley’s bass playing, the Fall reach a strange and ecstatic pocket here: “Mansion” recalls horror film music and the Deviants’ “Billy the Monster,” while “What You Need” pulls a line (“slippery shoes for your horrible feet”) from an episode of The Twilight Zone. Mark E. Smith goes absolutely mad in the sexy, electro-punk hailstorm of Brix’s “L.A.,” while “Gut of the Quantifier” summons the Doors and “Paint Work” is This Nation’s psychedelic, sprawling, stream-of-consciousness centerpiece. There’s something about this version of the Fall that I keep returning to. Maybe it’s the pop undertones and the record’s potent aroma of industrial, synthesized melodicism, which no doubt rubbed off on LCD Soundsystem twenty years later. Or maybe it’s because the Fall has never sounded so damn good. —Matt Mitchell

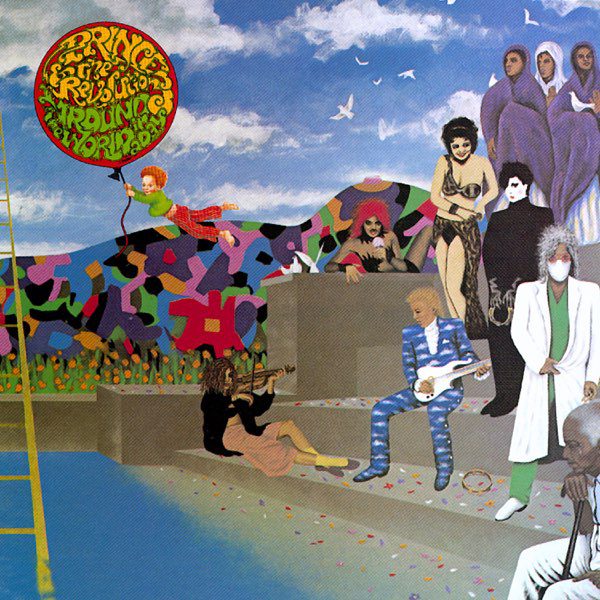

19. Prince and the Revolution: Around the World in a Day

Audiences have always looked at Around the World in a Day a certain way, considering that it came out after Purple Rain. It’s not a masterpiece on that level, but it’s still among Prince’s strongest outings. For me, it’s never been either/or. “And” is one of the greatest gift’s the Purple One’s catalogue continues to give us. Around the World in a Day has my favorite Prince song, the ever-fantastic “Raspberry Beret,” and two tracks I fell in love with for the first time only recently, “Pop Life” and “Paisley Park,” on it. And, like most of Prince’s albums not named Purple Rain or Sign ‘O’ The Times, Around the World in a Day didn’t get the critical lifespan it deserved. But that didn’t stop it from going 2x platinum in America and spawning multiple Top 10 singles forty years ago. It’s the penultimate credited appearance by the Revolution, and it’s a damn good one. SPIN called it Prince’s worst album then, but NME named it their Album of the Year. You know, I’ve always loved the Brits. —Matt Mitchell

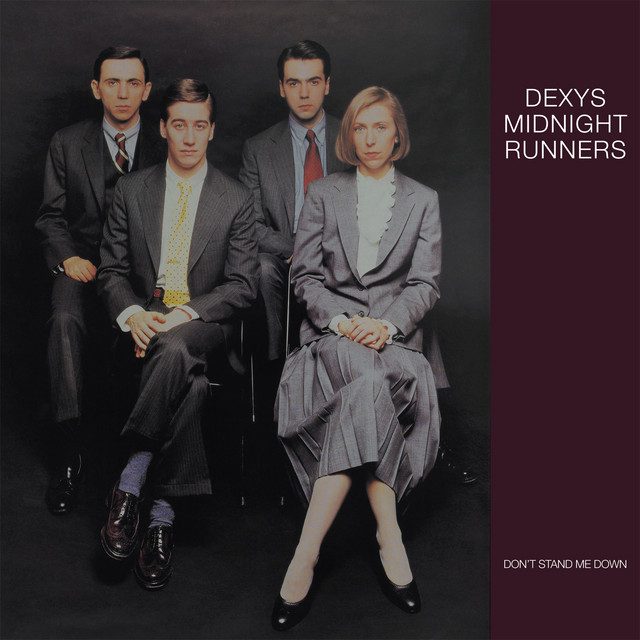

18. Dexys Midnight Runners: Don’t Stand Me Down

The task of following up a commercial juggernaut like “Come On Eileen” would be too tall for any band, let alone the one that made it. But Dexys Midnight Runners, after Too-Rye-Ay and “Eileen” both detonated into international success, ditched their overalls for Brooks Brothers suits and made a new wave, blue-eyed soul-tinged statement that was immediately dismissed by fans and writers alike. But Don’t Stand Me Down isn’t some jaded response to success; it’s a genuinely fantastic album, moonlit by the 12-minute “This Is What She’s Like,” which ought to be regarded as one of Kevin Rowland’s finest efforts, and the absorbing “Listen to This.” Don’t Stand Me Down wasn’t heavy on the brisk gestures but didn’t totally abandon the pop template. Instead, after numerous members quit the group, Rowland and his remaining bandmates let their ideas sprawl, turning in a bunch of catchy songs spanning more than five minutes. Considering that, half-a-decade earlier, Dexys were mythologizing themselves on Searching for the Young Soul Rebels, Don’t Stand Me Down sounds like a mask needfully slipping. The latter cost a lot of money to make and, at the time, generated a lot of ill will towards Dexys Midnight Runners. Everyone wanted them to keep up the “Come On Eileen” schtick. What the band responded with was a triumph I hope never gets left behind. —Matt Mitchell

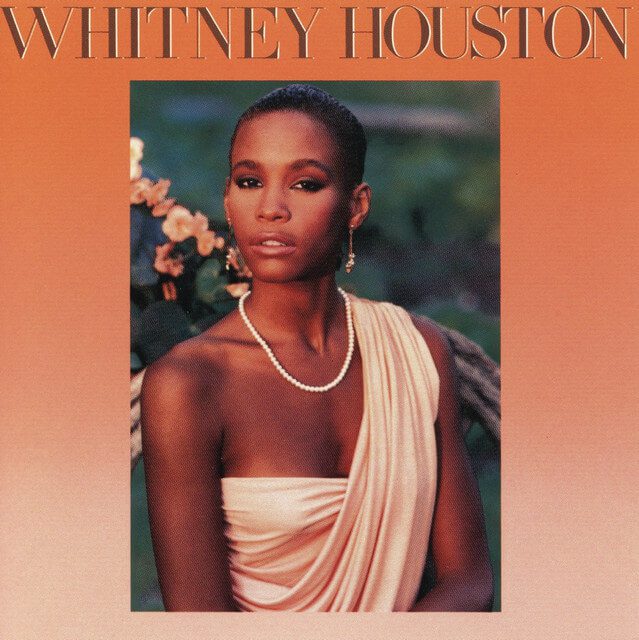

17. Whitney Houston: Whitney Houston

There isn’t much left to say about Whitney Houston’s singularity. In discussing her debut album, we can try pointing to Clive Davis, the producer that signed Whitney back in 1983 after seeing her perform at a New York night club. We could reminisce on the sales, the smashing success, how it was the first debut album to produce three number one singles—much less the first time a female solo artist completed such a feat. We could talk about these things, celebrate the storm that brought Whitney such profound and immediate grace, but God, what good would that do? Why would we spend our time thinking about anything but the sound? No one will ever sing like Whitney did. Anthemic ballads like “All At Once,” “Saving All My Love For You,” and “Greatest Love Of All” bat note for note with soulful dance tracks like “How Will I Know” and “Take Good Care Of My Heart.” Whitney Houston is pure sentiment—and I mean this in the best possible way. Sure, Whitney could sing the digits in a phone book and have made millions of listeners happy, but what she does choose to lend her voice to is monumentally affecting and has the everlasting emotional genuineness to never grow old. —Madelyn Dawson

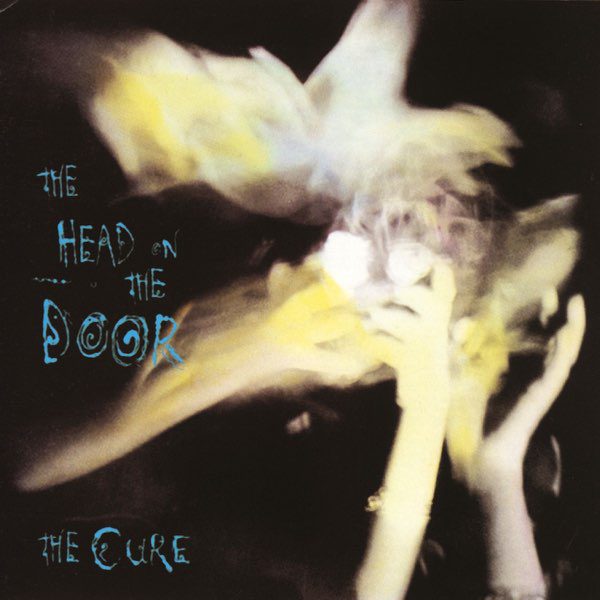

16. The Cure: The Head on the Door

My pick for the most underrated Cure album, The Head on the Door begins what I consider to be Robert Smith’s greatest period, in which this record gets followed by Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Disintegration, and Wish in a span of five years. But in 1985, fifteen months after releasing The Top, the Cure returned with Head on the Door and the best song opener of the eighties: “In Between Days.” That track alone gets this record on the list; “The Baby Screams,” “Six Different Ways,” and “Close to Me” make it a masterclass. The latter is a favorite of mine, thanks to it being a great example of the Cure’s embrace of bedroom pop after post-punk put some of their skin in the game. “Close to Me” arrived sounding nothing like the Cure’s previous efforts. Critics called it a “disco thing,” and Lol Tolhurst and Porl Thompson’s dueling keys get so razor thin you can hear breaths vibrating beneath them. The Head on the Door is such an impressive part of the Cure’s discography, with an implemented poppiness the band would return to again and again. Told through flamenco picking, dance-driven catchiness, and a candy-coated melancholy, The Head on the Door sounds like all you could ever need. —Matt Mitchell

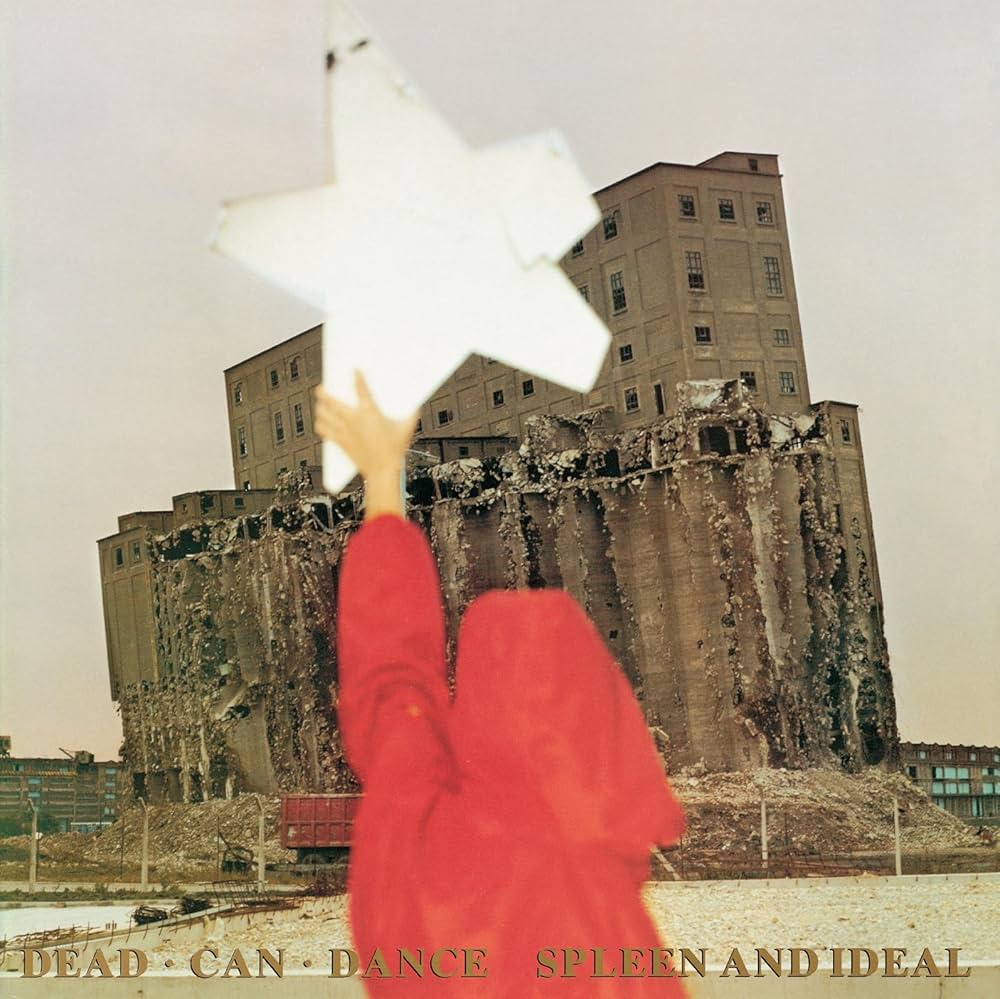

15. Dead Can Dance: Spleen and Ideal

An early release on 4AD, Spleen and Ideal contextualized Dead Can Dance’s neoclassical transformation. Gone were their goth-rock and post-punk beginnings, substituted with a monastic distribution of medieval influences, Latin references, and new-wave technology. It’d probably get labeled “darkwave” if it were released in 2025. Guitars were swapped out for cellos, trombones, timpanis, choirs, drum machines, and samplers; Lisa Gerrard and Brendan Perry put drones and bells into “De Profundis” and gently place a harpsichord into the string arrangement on “Enigma of the Absolute.” It’s a ceremonial affair, full of non-Western ideas and existing as this somber, ecstatic middle ground between Cocteau Twins and sacred, monophonic plainchants. Often filmic, moody, and boundless, Spleen and Ideal sounds like a religion. —Matt Mitchell

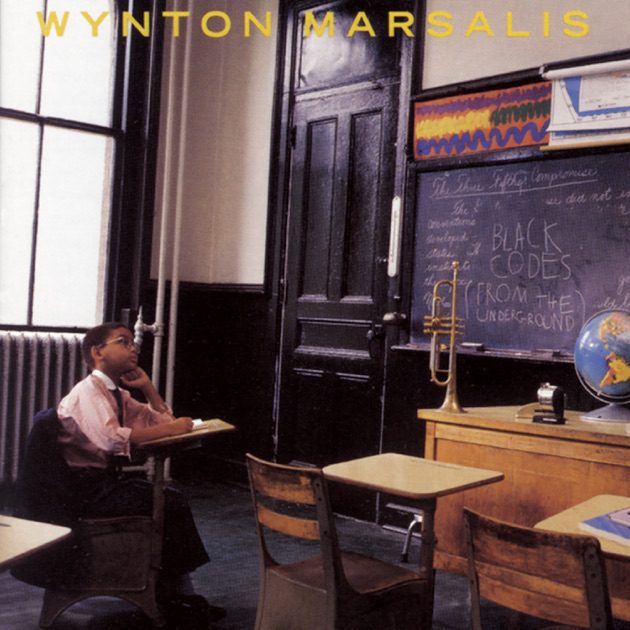

14. Wynton Marsalis: Black Codes (From the Underground)

By the time jazz music made it to the 1980s, the movement was not what it once was—not commercially, at least. Because of the innovation of twenty, thirty years prior, originality in later generations often paled in light of the greats. Gone were the days of Coltrane and Miles, their genius establishing a template few jazz players could even build upon. You’d be hard-pressed to find a bona fide all-time perfect jazz record from the eighties, but let me present you with one: Wynton Marsalis’ Black Codes (From the Underground). Marsalis’ conservative ideas about jazz and general dislike of post-sixties fusion have stifled his legacy for decades, but Black Codes is a post-bop triumph for the masses, and a great representative of the Young Lion era. The rhythms and harmonies benefit from great interplay and even greater tempo color. Black Codes is complex but not inaccessible, and Marsalis, surrounded by superior soloists, manages to establish himself as a minor-key great on it, using his classical background to inform his strongest jazz ideas. —Matt Mitchell

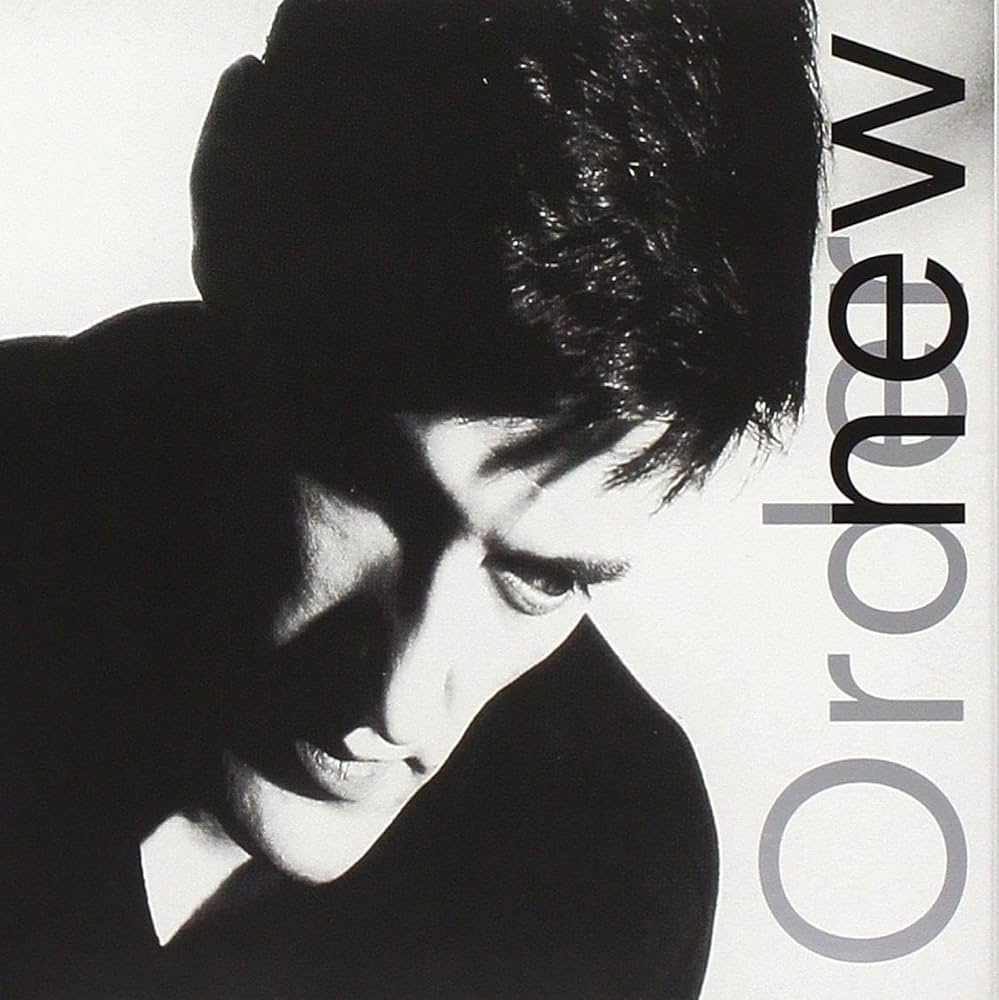

13. New Order: Low-Life

How do you respond to Power, Corruption & Lies? New Order did the impossible on Low-Life in 1985, as the ideas from the runoff of Joy Division got used up and the band fully pivoted to dance music. The music is soulful and joyous in a techno way, with adventurous percussion and sugary, moody synthesizer textures. It’s the kind of record you bring with you through life; humor and sweetness abound in strong melodies and electronic hideaways. I love Power, Corruption & Lies, but Low-Life, to me, signals New Order becoming a band. Bernard Sumner, Gillian Gilbert, Stephen Morris, and Peter Hook never sounded this good again; “Elegia,” “Sub-culture,” “Love Vigilantes,” “The Perfect Kiss”—these are songs you can fall in love with again and again. Sadness can be a rapture; Low-Life dares its listeners to reach for the light. —Matt Mitchell

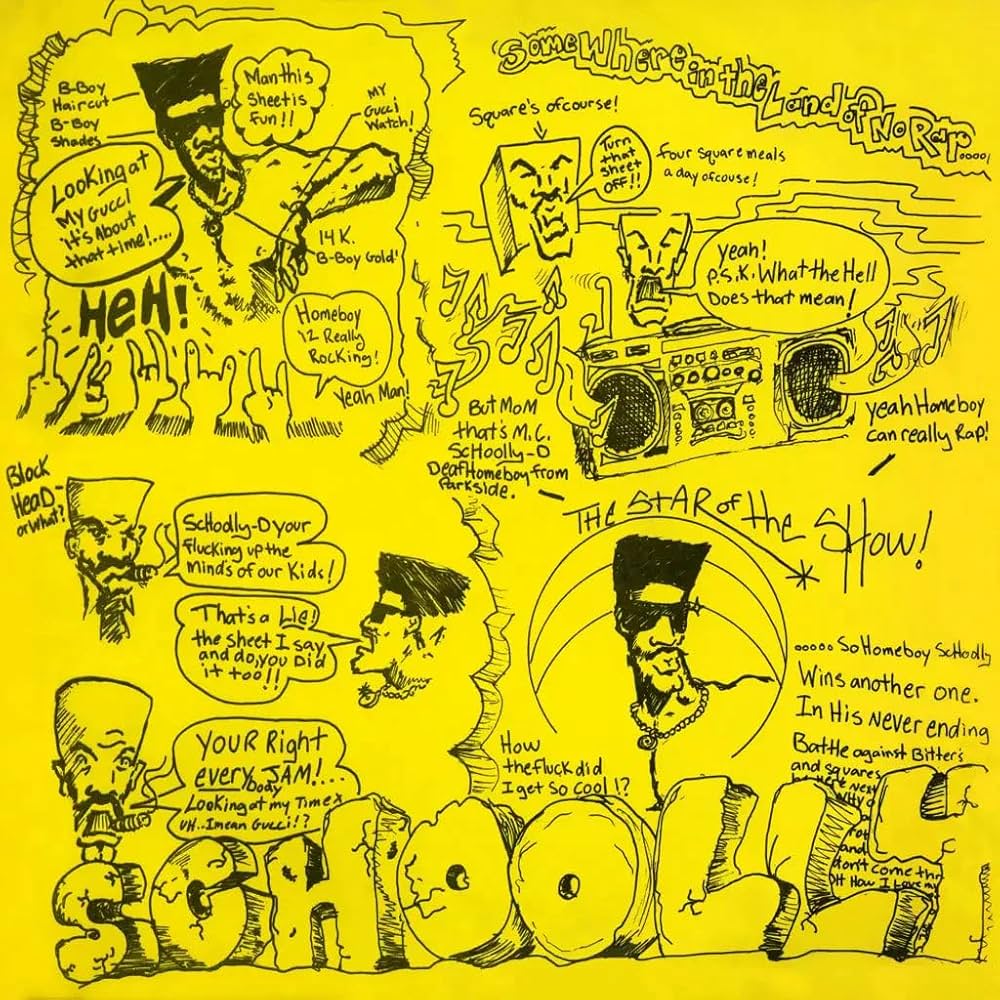

12. Schoolly-D: Schoolly-D

When Schoolly-D came out, Melody Maker’s Simon Reynolds called it “the most extreme hardcore hip-hop record I have ever encountered,” comparing it to the work of Swans and Killing Joke. Rap music looks a lot different now, and far more hardcore records have come out since Schoolly-D’s debut, but you can’t understate the role it played in the formation of gangsta rap forty years ago, spawning the likes of Ice-T, Public Enemy, and 2 Live Crew. With record scratches and beats supplied by DJ Code Money, Schoolly-D is a pivotal piece of history, summed up greatly by this bar: “Rock music is a thing in the past, so all you long-haired people can kiss my ass.” Schoolly-D is a love-letter to rap in one of its earliest iterations, with lived-in ideas and “hood lyrics for hood people.” Hearing these songs, like “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” and “Put Your Filas On,” is like a portal to the beginning of an all-time great thing. It’s a b-boy’s dream. —Matt Mitchell

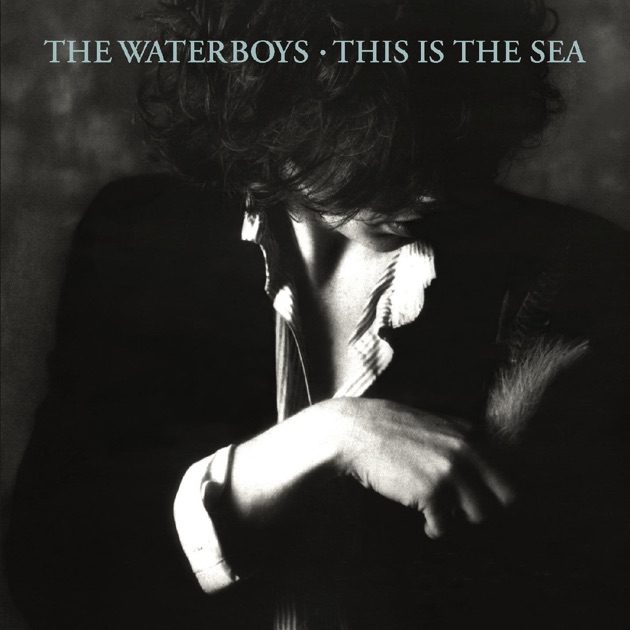

11. The Waterboys: This Is the Sea

The Waterboys’ third album was their first with a hit and last before keyboardist Kurt Wallinger left to form World Party. Landing right in the middle of the 1980s, it may be the biggest of their “Big Music” albums, crafting a sound from British folk, blues rock, Anthony Thistlethwaite’s wailing sax and the electronic flourishes of the era’s production experiments. That big sound is on display from the first track, the swelling wall of noise “Don’t Bang the Drum.” But the production leaves plenty of room for Scottish frontman Mike Scott’s literate lyrics to shine through on every song, finding spiritual inspiration through nature and human connection. On one of the band’s most enduring songs, “The Whole of the Moon,” Scott sings a stanza that pops in my head every time the moon looks too big to be real: “With a torch in your pocket / And the wind at your heels / You climbed on the ladder / And you know how it feels / To get too high / Too far too soon / You saw the whole of the moon.” —Josh Jackson

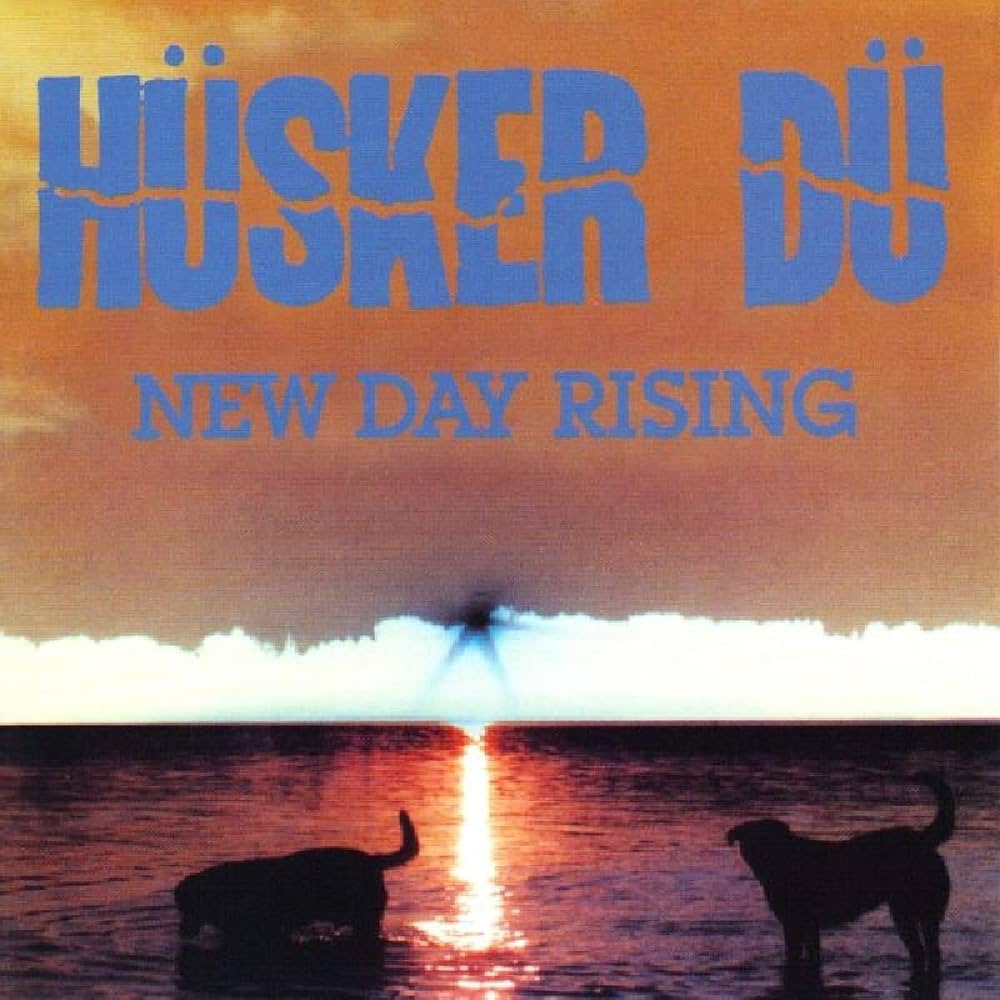

10. Hüsker Dü: New Day Rising

Hüsker Dü have gotten more than their fair share of Beatles comparisons over the years, and it’s definitely true in one way: They have at least three or four best albums. It doesn’t have the reputation of Zen Arcade, and Bob Mould shits all over the production in his autobiography, but New Day Rising is Hüsker Dü’s best collection of songs, and the most consistent example of the band’s trademark combination of hardcore virility and classic pop hooks. Somehow it looks larger than the equally great Zen Arcade and Flip Your Wig every year, despite all of them being solidly middle age at this point. It’s a prime influence on so many punk-derived sub-genres that have flourished in its wake, but more importantly than that, it’s an album that’s full of brilliant songwriting (“Celebrated Summer”! “Books About UFOs”!) and that always sounds good—even if it sounds like the bass is in the Witness Protection Program and Grant Hart built his drum kit out of old Raisin Bran boxes. —Garrett Martin

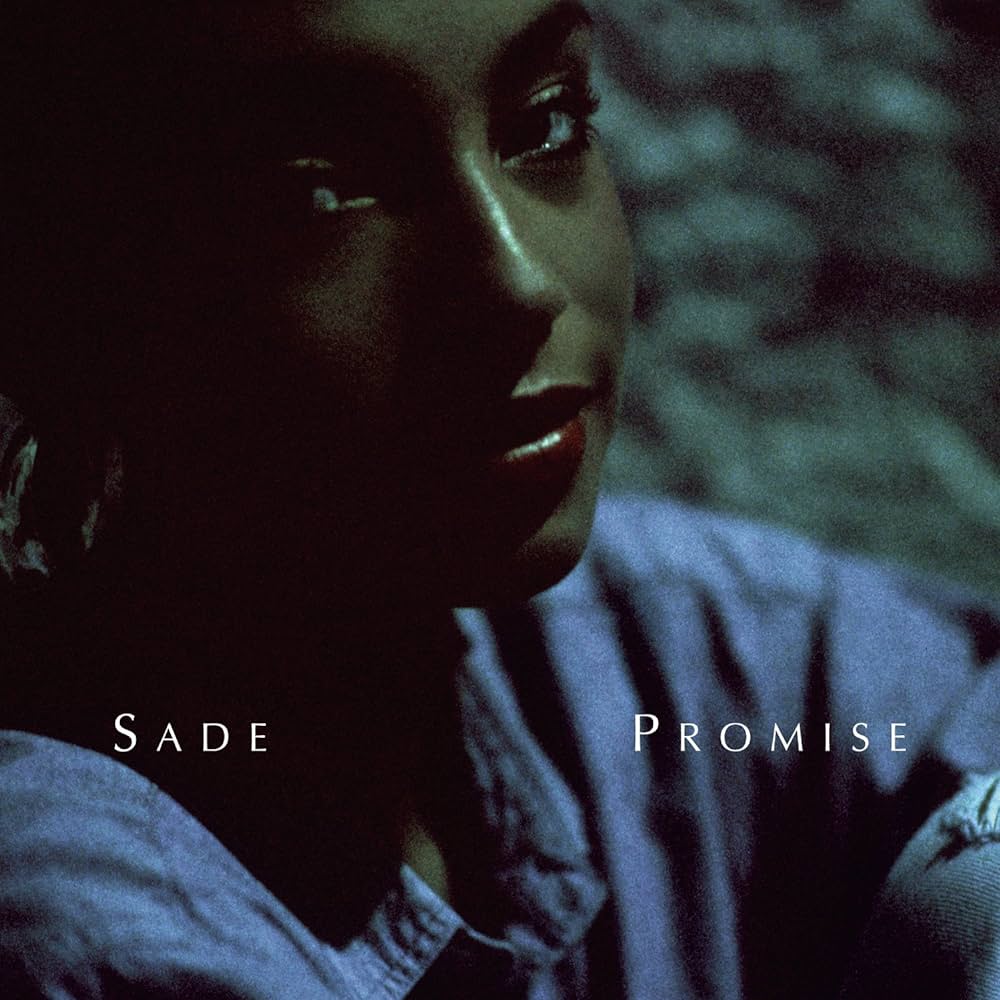

9. Sade: Promise

Sade Adu’s albums are like portals. Stronger Than Pride, Love Deluxe, and Lovers Rock came out in a 12-year span and could’ve been a masterpiece in any other artist’s discography. But it’s a trio that pales beneath the light of Adu’s first two efforts, Diamond Life and Promise. Diamond Life set the tone in 1984 as one of the decade’s best debuts, thanks to “Smooth Operator” and “American Psychos” being that good, and its successor operates in the same volume of elegance. Recorded at the Power Plant in London and Miraval in France, Promise went to number-one and produced a Top-5 single, “The Sweetest Taboo.” “Never as Good as the First Time,” “Is It a Crime?,” and ”Maureen” present some of Adu’s coolest, most tranquil singing, and the band (Stuart Matthewman, Paul S. Denman, and Andrew Hale) locks into itself around her. A million people bought into Promise forty years ago, and the magic of Sade’s music is that it still reaches those who crave it. —Matt Mitchell

8. The Pogues: Rum Sodomy & the Lash

I didn’t know about the Pogues until I watched My Own Private Idaho and heard “The Old Main Drag” in it. Then I tumbled into Rum Sodomy & the Lash, found “I’m a Man You Don’t Meet Every Day,” “Sally MacLennane,” “A Pair of Brown Eyes,” and “The Sick Bed of Cúchulainn,” and met the language of Shane MacGowan. I was a teenager and impressionable then, transfixed by a copious diet of Bob Dylan, and MacGowan’s poetry went below the asphalt I’d fallen onto, sending me into the most brutal alcoves of history. Rum Sodomy & the Lash sounds like an ashtray, and MacGowan is right there, tapping his finger on the end of a cigarette above it. It’s Celtic folk music full of funereal soul and these brilliant, imaginative celebrations and oddities. Some of the songs came from MacGowan’s own pen, while others came from voices and arrangers from a different lifetime altogether. But the best part about Rum Sodomy & the Lash, I’d reckon, is that it’s a songbook we’re still thumbing through. I’ve dog-eared a couple of pages already. —Matt Mitchell

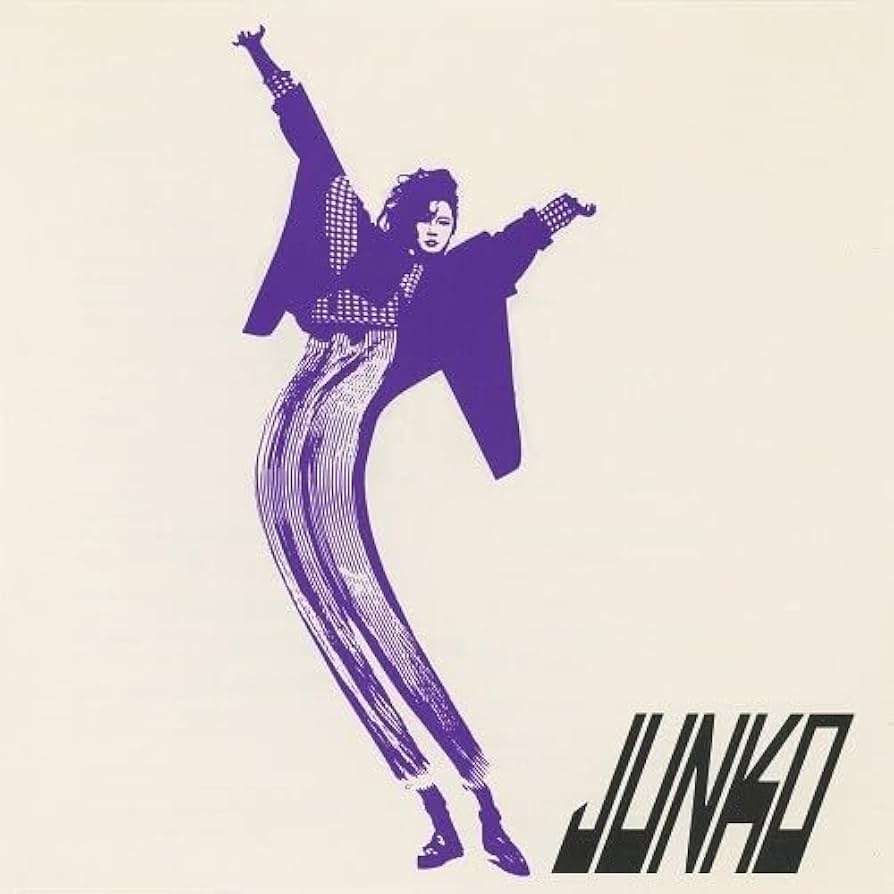

7. Junko: Communication

At minimum, Junko’s Communication is the best album cover on this list. At maximum, it’s on the mantle for “best J-pop albums of all time.” More often than not, it lands somewhere in the middle, establishing Junko as an idol and offering the world a Japanese companion to the Madonnas of the Western world. “Imagination” employs synth-funk, while “BELIEVING” is stripped-back yet somehow massive, colored by drums and Junko’s topline of charismatic singing. It may seem unfair to compare Communication’s high points to those on the American pop charts, but I promise it’s not. I’m a firm believer that a lot of English language pop music from forty years ago sounds, at the very least, really fabulous and rarely out of time. Repetitive? Sure, as all pop music across every era and pantheon often is. The thing about Junko is that most of her performances are more polished than their intercontinental counterparts. Step into the dubby, candy-coated Communication and you’ll be in pop-banger heaven. “Cashmere No Hohoemi” is one of the best songs on this list, period. —Matt Mitchell

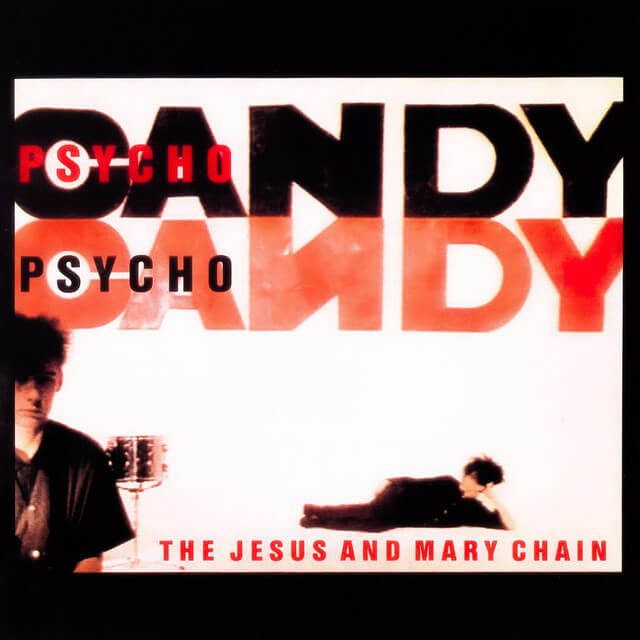

6. The Jesus and Mary Chain: Psychocandy

What do you get when you combine The Velvet Underground & Nico, the Shangri-Las and a German industrial band called Einstürzende Neubauten? Well, you get the Jesus and Mary Chain, a Scottish quartet built by brothers Jim and William Reid. After their dad lost is job at a factory, he gave 300 pounds of his redundancy money to the them, and they’d go out and buy a four-track and demo songs like “Upside Down” and “Never Understand.” Little did they know that they were on the brink of building one of the most essential noise pop and post-punk albums of all time (“Upside Down” wouldn’t make the album, but it was the Chain’s debut single). Psychocandy has become the not-so-lost masterpiece of the 1980s. It’s beautiful and perfect, yet largely overshadowed by efforts from the band’s peers—like Depeche Mode and New Order. But let it be known, Psychocandy is worthy of eternal greatness for the brilliance of “Just Like Honey” alone. The Jesus and Mary Chain were ahead of their time, yet they couldn’t have come alive at any other point in history than in 1985. It’s a meta, unbelievable truth. But Psychocandy is still registering 38 years later, and the work of Jim and William Reid is forever etched in stone. —Matt Mitchell

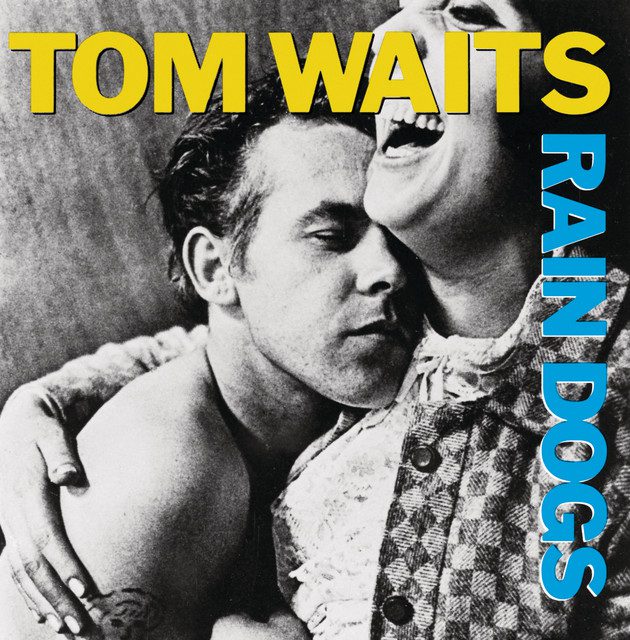

If 1983’s Swordfishtrombones saw Tom Waits stumble away from the barroom piano and wander into a junkyard, Rain Dogs sees him set up shop there and send out change-of-address cards. The album begins in the iron bowels of a ship set for Singapore and ends in drunken heartache on the streets of London town. In between, Waits takes us on a menacing, rhythmic romp through the rain-soaked haunts of the downtrodden and dispossessed. It’s a grimy, seamy, loving ode to the people and places decent society ignores, with Waits pushing his madcap kitchen sink production and near-pop songcraft to new levels of debauched sublimity. It’s his howling, Bukowski-esque masterpiece. —Matt Melis

4. The Replacements: Tim

Tim was a sonic turning point for the Replacements, who’d taken the raw, oral intensity and the scrappy beginnings of Let It Be and transposed them into these mature, understated ideas about growing up under the microscope of newfound fame—and it arrived such a far distance away from the bold, biting volume of Hootenanny and Sorry Ma, Forgot to Take Out the Trash. “Bastards of Young” sounds ferocious, primeval, titanic, and rowdy, while “”I’ll Buy” and “Little Mascara” ramble in their own crystalline pop perfections. And from the gauzy gallows imagery of “Swingin Party” to the honky-tonk-colored “Waitress In the Sky” and the jangly “Kiss Me On the Bus,” Tim is an untouchable assemblage of tracks. Paul Westerberg had found a lot of influence in everyone from Roy Orbison to Nick Lowe to Big Star, particularly in how each of them constructed pop melodies. In turn, Tim is a real halcyon affair brimming with golden, catchy rock cuts; lines like “unwillingness to claim us, you got no war to name us” and “if being alone’s a crime, I’m serving forever” and “everybody wants to be someone here” are still magnificently quotable forty years on. —Matt Mitchell

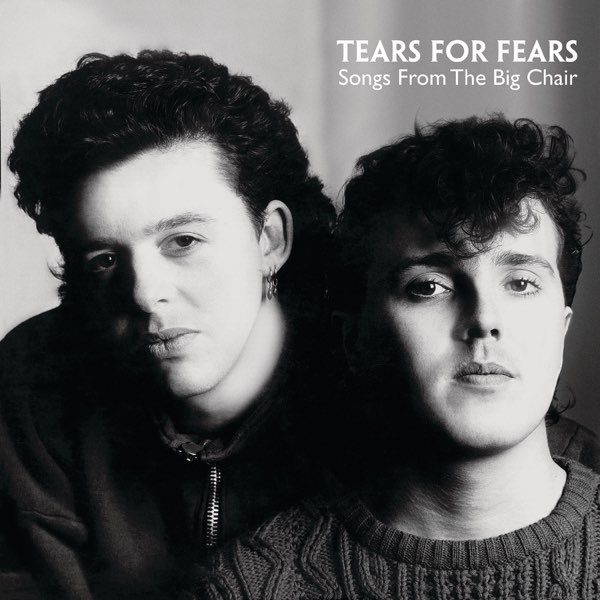

The greatest piece of music I have ever encountered remains Songs from the Big Chair, Tears for Fears’ gentle storm of decade-defining pop music—an album so great it topped the Billboard charts, spawned immortal hit songs like “Shout” and “Head over Heels,” and made Curt Smith and Roland Orzabal household names across generations. And my favorite song is, always, “Everybody Wants to Rule the World.” Few albums capture the lexicon of pop music from any era quite like Songs from the Big Chair. It’s a library of music’s strongest vernaculars, stretching across textures of new wave, synth-pop, prog, jazz, industrial and new age. Most artists who’ve attempted to harness such a deep wealth of sounds wind up making albums that sound like disjointed collisions. You can tap into any part of Songs from the Big Chair, even the ballads “I Believe” and “Listen,” and get a sense of why Tears for Fears’ music is one of pop’s great welcome mats. Tears for Fears found a pocket and made it profound, honoring the entanglements of living by embracing the tragedy that comes with it. If you were in Toronto in 1985 when “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” soared to #1, or if you were in my backyard 20 years ago when the song fell out of the sky and into my lap, there was no bigger band in the world than Tears for Fears. Time heals all wounds; so, too, does a record as necessary and human as Songs from the Big Chair. In November 1985, the band put out a documentary, Scenes from the Big Chair, to accompany the album, splicing together clips from music videos, live performances and interviews. There’s a scene near the film’s end, where a cameraman speaks to a photographer from Bravo, Germany’s equivalent of Tiger Beat. “Who are you photographing today?” he asks. “Tears for Fears, is that right?” the photographer replies, gesturing at a nearby Roland, who shakes his head before popping a grin. “No, we’re the Beatles.” —Matt Mitchell

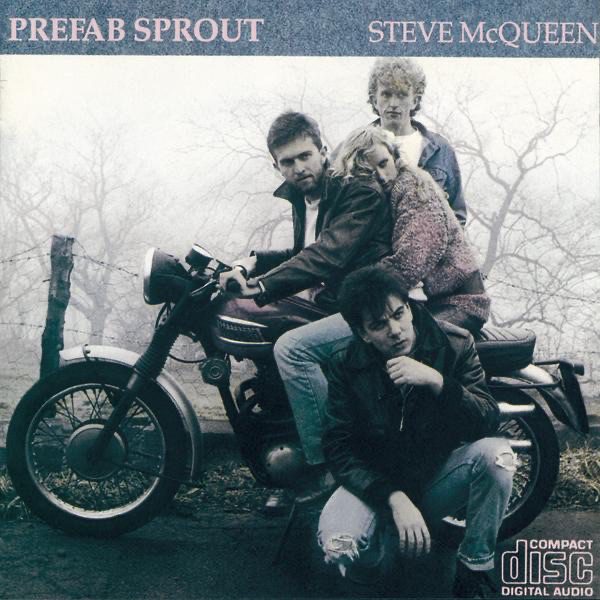

Steve McQueen is an album that arrived already out of time—free of condescension yet replete with humorous badges of infidelity, regret, and Catholic guilt; its influences were disarmingly old-school but its suite of digitally-captured music was impossibly cutting-edge. The songs sound totally eighties yet flourish without categorization. “Antiques!” Paddy McAloon’s voice beckons in the first passage of Steve McQueen. “Every other sentiment’s an antique, as obsolete as warships in the Baltic.” Maybe it’s a droll endorsement of his contradictory fashion of music-making, but he did want to be “the Fred Astaire of words” at some point. By 1985, he settled for being a pioneer of sophisti-pop alongside the Blue Nile and the Style Council. But Steve McQueen is a fantastic example of Paddy’s range of interests: His songs feature dapples of Bacharachian melodies, ZTT-patterned electronics, and muscular power chords with Brill Building affectations baked in. He was, after all, as much a student of Sondheim and Gershwin as he was McCartney and Bowie. Prefab Sprout, through his stewardship, had the grandeur of Sinatra and the glamour of Prince. Thomas Dolby plugged all of it in and trimmed the fat. Under the banner of Prefab Sprout, Paddy was “too nervous a songwriter to incorporate a big chorus,” but his intelligence evoked a strangeness, in prismatic soups of language still lit by contemporary lyricists like Arctic Monkeys’ Alex Turner and the Magnetic Fields’ Stephin Merritt, both of whom have picked up the proverbial torch for the post-Steve McQueen generations. In less than two years, we got these albums: A Walk Across the Rooftops, Hounds of Love, Please, and The Colour of Spring. Prefab Sprout played into this emerging, progressive sound, too—ratcheting up their breathy vocal EQ and masking Paddy’s literary doom with cresting jazz euphonies and folktronica pastorals. A half-decade of Thatcherism later, the band’s idyllic deliverances were a necessary, “cowboy” contrast to the rising levels of “aspirational pop” music in England. Had the Replacements not been so drunk and debauched, they would have been America’s greatest compliment to Prefab Sprout. There are more than enough entries into pop relevancy that sound not of this world. Paddy and Dolby’s work together on Steve McQueen, however, challenges the listener to imagine something divine with both feet on the ground. Few songs in the English language speak to that surfacely expanse like “Bonny.” —Matt Mitchell

Up until 1985, Kate Bush’s pioneering avant-pop had been of an acquired taste, resulting in a few runaway hits but comparatively modest commercial performance. However, once she released Hounds of Love, it seemed as if the globe suddenly acquired that taste all at once. Hounds of Love proved that prog could be catchy, feminine and memorable, offering all-time earworms like “The Big Sky,” “Cloudbusting,” and the perennial hit “Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God).” Since charting at #3 in the UK and #30 in the US in 1985, “Running Up That Hill” has returned to the charts whenever featured in a major cultural artifact: in 2012, it peaked at #6 in the UK following its use in the closing ceremony at the London Summer Olympics, and in 2022, the song reached #1 in 8 Anglophone and European countries when young audiences first heard its repeated use in Stranger Things’ fourth season. The song and album have a time-defying appeal that keeps Kate Bush’s name at the forefront of all things weird, and considering the vitality of avant-pop in today’s musical landscape, Kate Bush is owed dozens of thanks. —Devon Chodzin