Forty years ago, the biggest song in America was the soundtrack to a training montage in the third Rocky movie. Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder teamed up for a well-meaning if overly simplistic and sentimental anti-racist duet. And Olivia Newton-John’s pop single “Physical” released at the end of 1981 became the best-selling single of 1982. But it was also the year a number of legends released some of their best albums—Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen and Prince. Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five helped the emerging hip-hop scene gain broader attention. And dozens of artists bubbling under the surface pushed the post-punk, art-rock and New Wave sounds in new directions.

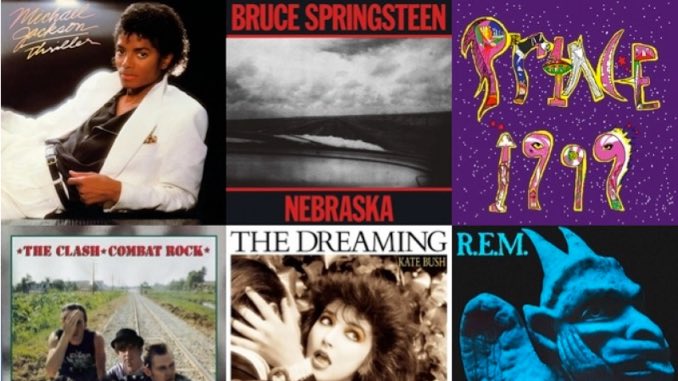

Here are the 20 best albums from 1982:

20. INXS: Shabooh Shoobah

The third album from INXS was their first to make a splash outside of Australia. Between the album opener “The One Thing” and closer “Don’t Change,” Shabooh Shoobah captured some of what had made the New Wave six-piece a must-see live act in their home country. The early ska influences are still present on songs like “Black and White,” but the interplay of guitars and synths on “The One Thing,” along with Kirk Penguilly’s sax on “Golden Playpen” and the arena chorus of “Old World New World” provided the blueprint for the many hits that would follow. And the sweeping “Don’t Change” would go down as one of the best songs Michael Hutchence, Garry Gary Beers, Penguilly and the three Farris Brothers would ever record. —Josh Jackson

19. X: Under The Big Black Moon

In the early ’80s, no punk band extended an olive branch to the early generations of rock as well as L.A.’s X. On their first two albums Los Angeles and Wild Gift, main songwriters John Doe and Exene Cervenka wrote gnarled lovesick songs juxtaposed with a respect for classic pop songwriting and rockabilly pomp. On their third album Under The Big Black Moon the band re-teamed with producer Ray Manzarek of The Doors to strip away a fair share of the distortion and speed that hid elements of their songwriting in the past. While other punks in the scene would view the movement as a recalibration that dissolved everything that came before it, X tested their fans on how much they would be willing to go back. Guitarist Billy Zoom and Drummer D.J. Bonebrake dig and swing in equal measure on songs like “The Hungry Wolf,” “Motel Room in My Bed,” and the title track, but also showcased a tasteful and tender side to their playing on the doo-wop inspired ballad “Come Back to Me” and the Ruth Etting 1930’s radio hit “Dancing With Tears in My Eyes.” The album’s shining moment is its closer “The Have Nots” which called bullshit on Ronald Reagan’s idea that blue-collar Americans should deify the wealthy in the off-chance that one day they could be considered members of the same country club. Is dawn for the working class drawing nearer or is it already behind us? With Under the Big Black Moon, X capped off a trio of classic records with an album that incentivized the punks to view their place in rock and roll as part of a larger continuum rather than agents of chaos looking to tear the whole thing down from within. —Pat King

18. Lou Reed: The Blue Mask

Common threads aren’t easy to find in Lou Reed’s career—this is a point of pride for the man who hired Metallica to stinkbomb 2011 after a seven-year studio sabbatical. But humility underscores the lifelong egotist’s most beloved work, and The Blue Mask focuses on confessions and bareness, not to mention loveliness, which he certainly can’t take full credit for—Robert Quine’s skyscraping guitar and Fernando Saunders’ romantically deployed bass help conjure all the right moods, from languidly rhapsodizing about “Women” (“I think they’re great/ They’re a solace to a world in a terrible state”) to Oedipal raging in the grinding title tune (“I’ve made love to my mother/ Killed my father and my brother/ What am I to do?”). “Average Guy” is played for jest. —Dan Weiss

17. Elvis Costello & The Attractions: Imperial Bedroom

Elvis Costello’s seventh album and sixth with The Attractions, Imperial Bedroom found the future Rock and Roll Hall of Famer following up the country thrust of Almost Blue by committing to stately Tin Pan Alley pop, a la Trust’s “Shot With His Own Gun.” He did so not with the help of his go-to producer Nick Lowe, whose “bash it out” approach was so key to Costello’s first five albums, but rather with Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick, who was more of a “tart it up” kind of guy. Imperial Bedroom is miles from the self-described “spiky and sour” sound of Costello’s pub-rock beginnings, its literary tales of troubled romance written on the piano and rendered with grand ambition. A 40-piece orchestra animates the Sgt. Pepper’s-esque “…And In Every Home,” while regal horns, Mellotron and organ play musical chairs with Costello’s chameleonic vocals on “Pidgin English.” Accordion and piano war for your attention amid “The Long Honeymoon”’s story of “a wife who’s wondering where her husband could be tonight”—conversely, there’s little to distract from Costello’s longing croon on the Chet Baker-inspired (and, later, -covered) torch song “Almost Blue.” The Imperial Bedroom era may have found Costello reeling from his meteoric rise (he was “disgusted, disenchanted, and occasionally in love,” he wrote in its liner notes), but the album itself is defined by a sense of sonic adventure one still can’t help but be swept up in. —Scott Russell

16. Duran Duran: Rio

If Duran Duran’s sophomore album had produced just one monster hit single, it probably would’ve still been considered a success, but Rio isn’t just a success—it’s the band’s greatest achievement, a double-platinum record that featured singles like “Rio,” “Hungry Like the Wolf,” “My Own Way” and the epic “Save a Prayer.” It also marks a turning point for the band as they finally were able to break through in the States, where New Romanticism had less appeal than in the UK. That subtle aesthetic shift from New Romanticism to synthpop—coupled with the band’s video success on MTV—made them a smash and helped usher in the Second British Invasion. —Bonnie Stiernberg

15. Donald Fagen: The Nightfly

When certain great songwriters reach their early 30s, they reassess and write about the particulars of their childhood with fresh eyes (see: Plastic Ono Band, Like a Prayer). Donald Fagen reached this point in 1982, when he released this slyly retro masterpiece of a solo debut. On tunes like the Cold War come-on “New Frontier” and the Caribbean-flavored “The Goodbye Look,” the Steely Dan frontman riffs on the themes of his suburban 1950s childhood through the eyes of a boy “of my general height, weight and build,” as he playfully put it in the liner notes. At first blush, The Nightfly’s meticulously slick jazz-pop sounds like the logical continuation of Steely Dan’s original run of LPs. But with Walter Becker out of the mix, the album has a warmer, more nostalgic glow. When Fagen sings the naïve refrain of “I.G.Y.” (“What a beautiful world this will be/What a glorious time to be free”), you almost believe him. —Zach Schonfeld

14. Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five: The Message

Seven years before Chuck D declared that “rap music is the CNN of the ghetto” in 1989, Grandmaster Flash and his crew were serving up street-level portraits of life in the Bronx on The Message, their first full-length album. Pushing beyond the imperative to boast that characterized the lyrical style of a lot of early hip-hop MCs, Grandmaster Flash, Keef Cowboy, Melle Mel, Kid Creole, Scorpio and Rahiem set a new standard, balancing playful songs like album opener “She’s Fresh” with socially conscious sentiments on the title track, which took a hard look at poverty and the socioeconomic lure of crime in the inner city. The Message was a watershed for hip hop, demonstrating that a genre rooted in block-party entertainment could, in fact, deliver a potent message while also getting booties moving. —Eric R. Danton

13. Roxy Music: Avalon

A sophisti-pop landmark, Roxy Music’s final effort was also their most successful—the English band’s only album ever to go platinum in the States. Jazzy and atmospheric, Avalon shares its title with a sacred island from Arthurian legend, which Bryan Ferry envisioned as the “ultimate romantic fantasy place.” Its 10 tracks, which run a brisk 37 minutes, are loosely organized around this concept, as if Roxy Music are grasping at an Eden that forever remains just beyond their reach. “You run through here with your words of sand / I can nearly understand,” Ferry croons amid the airy synth-funk of “The Main Thing”; his reverb-drenched voice parts reeds of bass, sax and piano on “While My Heart Is Still Beating” as he opines, “All of those people / Everywhere / Ever so needing / Where’s it all leading?” And on the band’s biggest hit and Avalon’s opener, the eternal “More Than This,” they yearn and savor in the same breath, finding their destination—their Avalon—in the journey itself: “More than this / You know there’s nothing / More than this.” A seamless work of carefully considered, economic lyricism and smooth, self-assured instrumentation, Avalon found Roxy Music sanding down their sound’s sharp edges and, in doing so, polishing a gem. —Scott Russell

12. The Cure: Pornography

It took teetering on the brink of insanity for Robert Smith to find his signature voice. The Cure’s third album, Pornography, was recorded during a blistering three-week sprint of drug use and studio excess, with Smith battling extreme depression. But that madness coalesced into the band’s first signature album, built on spidery rhythms (“One Hundred Years”), murky guitars (“The Hanging Garden”) and Smith’s magnetic warbling. The band made stratospheric songwriting leaps later in the decade, but they never again conjured atmospheres this unsettling. —Ryan Reed

11. Laurie Anderson: Big Science

An eccentric performance artist records an avant-pop song built around a sample of the repeated syllable “Ha,” lands a fluke hit in the U.K., and winds up with a seven-album deal with Warner Bros. This is the strange story behind Laurie Anderson’s visionary debut, a work of avant-garde wonder that is entirely unlike anything else released in 1982. Swathed in black humor and social satire, Anderson’s sound pieces resemble aural short stories more than songs, whether she is playing a fatalistic pilot on “From the Air” or spoofing suburban commercialization on the haunting title track. Of course, “O Superman (for Massenet)” is the classic, its vocoder-tinted utterances sounding like radio dispatches from a dystopian future. This album’s influence has stretched far and wide, encompassing Spiritualized (who covered “Born, Never Asked”), David Bowie (who covered “O Superman”), and of course Anderson’s future husband Lou Reed. —Zach Schonfeld

10. The Fall: Hex Enduction Hour

If I could only have one album from The Fall —and if that album can’t be an EP (sorry, Slates!)—then Hex Enduction Hour would get the nomination after an unusually rancorous brokered convention. Basically it’s classic second-wave Fall at the peak of the twin-drummer/pre-Brix era, a lumbering rock ’n’ roll juggernaut built on plodding repetition and Mark E. Smith’s caustically hilarious lyrics. In classic Fall fashion, both band and record are entirely indifferent to whatever an audience could theoretically want. —Garrett Martin

9. Mission of Burma: Vs.

“Post-punk” is about as vague and ill-fitting as most genre names. It could mean music that was more complex or more stripped down than punk, catchier or noisier. Or, when you talk about Mission of Burma, almost all of those things at once. Vs., the only album they released during the 1980s, before reuniting in the 21st century, is as punk rock as wall of noise, with Roger Miller’s guitar and Martin Swope’s tape effects washing over Clint Conley’s melodic basslines and Peter Prescott’s complex drum patterns. It’s a furious sound that’s both passionate and cerebral, and a pivotal influence on some of the best underground guitar rock of the last 30 years. —Garrett Martin

8. Richard & Linda Thompson: Shoot Out the Lights

If the best folk-rock music marries the patience and lessons of the past to the technologies and crises of the present, this is one of the greatest folk-rock albums of all time. Written, recorded and toured as the marriage between the two singers was crumbling, the album seems to teeter on the edge of reconciliation and rupture. In songs like “Walking on a Wire,” “Just the Motion” and “Don’t Renege on Our Love,” relationships are a tightrope high above the crowd, a small boat amid big waves and a faltering promise. On the title track, Richard seems ready to aim his rifle at the overhead lamps rather than confront the problems, but on the majestic “Wall of Death,” he’s willing to climb aboard the most dangerous ride at the carnival if that’s what it takes to stay alive. Richard has always written lovely melodies, but it’s seldom as obvious as it is here when Linda’s gorgeous voice handles the three ballads. —Geoffrey Himes

7. Bad Brains: Bad Brains

When four aspiring jazz-fusion musicians from Washington, D.C., heard bands like The Buzzcocks coming out of England’s ’77 punk explosion, they decided to reconsider their plan of attack. As a result, they would change the course of punk as it soldiered on into a new decade. Dropping their original name Mind Power for the infinitely cooler Bad Brains, the band became pioneers of what we now call “hardcore.” With their galloping and technical speed led by one of the most dynamic singers of any genre—Paul D. Hudson, known to all as H.R.—their first official self-titled full-length from 1982 remains a north star for musicians with an energy that can’t be contained within practice room walls. The spotless tracklist isn’t “all-killer” as much as it is all “motivation,” as anthems like “Sailin’ On,” “Big Take Over”, “Pay To Cum”, and “Banned In D.C.” jolt you into action as hard as a butter knife in an electrical socket. The classic “Attitude” took the “Positive Mental Attiude” message from author Napolean Hill’s self-help book Think and Grow Rich and spawned it into countless “P.M.A” tricep tattoos, and it’s easy to understand after hearing H.R.’s impassioned rallying cry over guitarist Dr. Know’s scorching fretwork. But what set Bad Brains apart from their peers—aside from their speed—was their ability to weave in their love of reggae and dub into the album’s runtime. With all four members of the group being black and identifying as Rastafarian, Bad Brains destroyed the any whiff of punk’s musical parameters that seemed to be tightening at the time as well as the idea that it was a form of music designated for “white rioters.” As the Bad Brains sailed on in the 40 years since their self-titled, they would find scattered moments of brilliance but never re-capture the lightning bolt hitting the capital building on the album’s cover. One strike is all you need. —Pat King

6. R.E.M.: Chronic Town

Sure, it’s just five songs, but I can’t think of a more important EP than R.E.M.’s debut. The B-52’s had already put little Athens, Ga., on the map but quickly left for New York, leaving behind a community of students and townies clamoring for the party they’d already gotten a taste for. R.E.M. more than filled that void, and with Chronic Town, produced by Mitch Easter, the buzz quickly spread. Peter Buck’s jangly Rickenbacker on “Wolves, Lower” would become a staple of the quartet, buoyed by Mike Mill’s equally frantic bass and Bill Berry’s steady beat. On top of it all were the lovely mumbles of Michael Stipe. You might not be sure of the lyrics of “Gardening at Night” (or really understand the impressionistic Southern gothic musings if you did), but you sure wanted to sing along. —Josh Jackson

5. Kate Bush: The Dreaming

I’ve listened to The Dreaming countless times, and I still struggle to believe it’s a real thing that someone made and released, and that people continue to listen to it. It’s my favorite Kate Bush album by a mile. Bush chose to produce the album herself (her first time doing so), giving her the freedom to experiment with no restraint. It took several engineers and an extended recording process to get what she wanted: something maximal, violent and wild. Where Never For Ever operated as Bush’s dark fairytale with specks of light dazzling across its runtime, The Dreaming takes both the euphoria and the darkest depths to extremes, using each vignette to capture an artist at a crossroads, wondering whether she can actually “have it all” or if she’s been lying to herself this whole time. Most of the tracks find Bush wearing a mask, exploring the history of oppressed groups, tragic historical figures and film character archetypes in a hunt to take on as many guises as she can. “There Goes a Tenner” sees her as an incompetent bank robber, “Pull Out The Pin” embroils her in the fight for survival as a North Vietnamese soldier (that final repeated chorus of “I love life” sends chills down the spine) and the title track finds her traveling through the Australian Outback, condemning the destruction of indigenous people’s land by white Australians. She even writes from the perspective of Harry Houdini’s wife communing with the spirit world on the gorgeous “Houdini,” hoping their bond can transcend the magician’s death and communicating with him through a medium. In contrast, the moments where the masks come off explore Bush’s sudden bout of imposter syndrome. “I must admit, just when I think I’m king / Just when I think everything’s going great / I get the break,” she sings on the polyrhythmic, sample-heavy opener “Sat in Your Lap,” vying for artistic autonomy without knowing whether such a thing is fully possible. “Suspended in Gaffa” finds her doubt nearly eating her alive, searching for any divine figure who wants to show themself and tell her what her purpose is. No other album captures womanhood in all its rage-filled, grotesque glory like The Dreaming does. A witches’ brew of sweat, plenty of blood and the desire to grow into an all-consuming being that can swallow any obstacle whole (something women had been told for centuries they weren’t supposed to be), it stands as an unfiltered testament to the wrath of Bush’s vision, as well as one of her crowning creative achievements. —Elise Soutar

4. The Clash: Combat Rock

This was last Clash recording to feature the classic lineup of Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon and Topper Headon. Coming after the sprawling glories of the double-disc London Calling and the triple-disc Sandinista, it was dismissed as the beginning of the decline, despite being the band’s biggest commercial success. But the two hit singles, “Rock the Casbah” and “Should I Stay or Should I Go,” were great rock ‘n’ roll radio songs (as was the latter’s B-side, “Straight to Hell”) and demonstrated that the band was learning the value of groove, hooks and concision. They were constantly evolving, and it’s too bad that they fell apart before taking the next step. —Geoffrey Himes

3. Prince: 1999

After dropping four albums consecutively, 1999, immediately, became Prince’s widest, and most musically ambitious, landscape of sex and love. He populated the whole thing generously with synthesizers, drum machines, sensual moans and screaming guitars. It’s a text that’s influenced three decades of techno and art pop. Built atop a funkified falsetto he’d patented four years earlier, 1999 was the perfect test-drive for a sound Prince would fully harness on Sign o’ the Times five years later. Yet, it was here, in-between the shimmying struts of showboating, apocalyptic electronica, where the multi-instrumentalist fully dove into the glamorous androgyny that codified him as such a singular, auteur figure in the 1980s. 1999’s first three singles (“1999,” “Little Red Corvette,” “Delirious”) each peaked high on the Billboard Hot 100 and “International Lover” garnered Prince his first ever Grammy Award nomination. “Little Red Corvette,” an unfathomably hot, metaphor-drenched, post-disco rock number about casual one-night-stands, helped Prince carry his funk roots over the line into full-fledged pop rock (a transition he’d fully embrace two years later on Purple Rain). But the record’s centerpiece is the nine-minute-long, bursting heart of “Automatic,” in which he fashions a sonic that is as accessible as it is indescribable and provocative, with insatiable, well-paced lyrics about the art of pleasure and coveting (“I’ll rub your back forever, it’s automatic” and “Baby you’re a purple star in the night supreme”). The song is Prince’s forgotten opus, just as 1999 is the masterpiece that preceded masterpieces. When the record begins, he asks what we should all make of the end of the world; by its end, there is only one right answer: we must go out grooving, with our bodies pushing against one another lovingly. 1999 made Prince one of the first Black artists featured heavily on MTV’s rotation. The record stands as a critical document of his “Minneapolis sound,” which defined the decade’s R&B successes, and its popularity made him a star and forced the stratosphere to chase after him. As he sings on “Automatic”: “Fasten your seat belts / Prepare for takeoff.” —Matt Mitchell

2. Bruce Springsteen: Nebraska

One of the finest hours of an American music icon, Nebraska is about as harrowing as Bruce Springsteen’s output gets. It’s a (the?) prototypical post-success stylistic swerve, arriving as it did in the wake of The River, Springsteen’s first number-one album. Inspired by that record’s title track, as well as the music of Suicide, Springsteen dove headlong into darkly detailed storytelling about hard-luck characters carving out desperate lives on American society’s margins, saddled with “debts no honest man could pay.” He famously recorded the demos that would become Nebraska alone on a Tascam four-track, releasing them unaltered after they proved resistant to translation into full E Street Band songs. On the opening title track, Springsteen assumes the perspective of serial killer Charles Starkweather, observing matter-of-factly amid plucked acoustic guitar and mournful harmonica, “Well, sir, I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.” The point-of-view character in the indelible “Atlantic City” has everything to lose (and does); the stark “State Trooper”’s, nothing. Even as he closes out the album with a flicker of hope—”Still, at the end of every hard-earned day / People find some reason to believe”—Springsteen is haunted by the grim realities of American life (“Down here, it’s just winners and losers and ‘Don’t get caught on the wrong side of that line’”), as if unsure whether that hope is what keeps you alive, or what kills you. —Scott Russell

1. Michael Jackson: Thriller

Every now and then, an album comes along that we can all agree upon. It’s impossible to talk about the music of the ’80s without mentioning this watershed record by the King of Pop. The Quincy Jones-produced 1982 classic was able to transcend genre and appeal to fans of all demographics, and it’s not surprising that it remains the best-selling record of all time, with 110 million copies sold. Since its release, countless others have tried to replicate its pop perfection, but no one can touch the killer bassline on “Billie Jean,” Jackson’s impassioned snarl on “Beat It,” the danceability of “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin” or, yes, even Vincent Price’s campy spoken-word part on the omnipresent title track. It produced a whopping seven Top 10 hits for Jackson, and while that’s obviously not a measure of artistic merit (we’re looking at you, Katy Perry), it’s safe to say that Michael Jackson was pop music in the ’80s and that the legacy of Thriller is one that cannot be ignored. —Bonnie Stiernberg