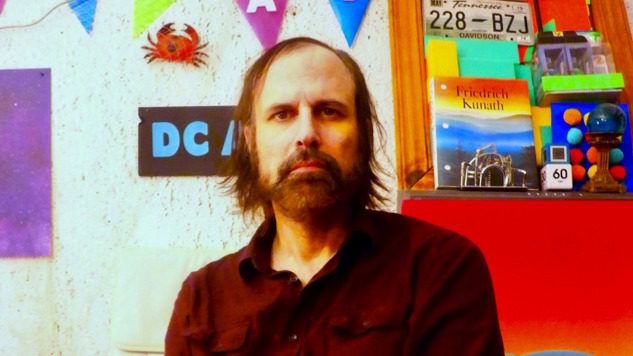

Nearly a year’s passed since the world lost David Berman, and it’s tempting to think about what he would’ve made of the time since he’s been gone. Coming up in the same college rock scene as Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastonvich, Berman would often find himself unfairly lumped together with his contemporaries in Pavement. In reality, though, he was a singular voice. Witty, melancholy, profound, low-brow, poetic—in his writing and music, he found a way to channel all these forces into little gems that gleamed for whoever took the time to look. His passing saw a flood of tributes that crossed generational lines, with everyone from Bill Callahan and Kurt Vile to First Aid Kit and Stef Chura showing the mark Berman and his music left on their lives.

For most of his career, Berman released music under Silver Jews, a project started in 1989 with his college friends Malkmus and Nastanovich. The lineup would change dramatically across the band’s six studio albums, but with Berman’s writing and wry delivery always resting at its core. His presence for fans was defined almost as much by his absence. Silver Jews never embarked on a single tour until 2005 with the release of Tanglewood Numbers. And shortly after that, in 2009, Berman announced that he was retiring from music, with Silver Jews’ final show inside a cave at the Cumberland Caverns. Almost a decade of silence followed until out of the blue Berman announced he had a record coming in 2019 under the new band name of “Purple Mountains.” Recorded with members of Woods, the self-titled album quickly found both praise and concern as a brutally sad, but clever, lovingly produced and fitting return for one of the sharpest lyricists in music. While this would tragically mark the end of Berman’s musical legacy, what he left behind was a trove of beautifully heavy music. Here are 15 of his best songs.

15. “We Are Real”

About halfway through American Water Berman gave one of his most lyrically pointed tracks with “We Are Real.” “Won’t soul music change now that our souls have turned strange?” he asks, searching for something that’ll affirm his reality instead of masking it. The music hits a perfectly simple balance of tension and release to mirror Berman’s muted indignation in some parts (“We’ve been raised on replicas / of fake and winding roads / and day after day, up on this beautiful stage / We’ve been playing tambourine for minimum wage”) and defiant hope in others (“When on and off collide / We’ll set our souls aside and walk away”). —Jack Meyer

14. “The Sabellion Rebellion”

This track from the split 7’’ between New Radiant Storm King and the cheekily titled Silver Jews & Nico is a hidden gem within the Jews’ early recordings. Hinting at some of the chaotic energy of Berman, Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich’s college-rock days, the song has a perfectly sloppy ’90s lo-fi sound, with fuzzy guitars, slippery drums and a rousingly simple refrain of “Welcome to the sabellion rebellion.” It’s more of a testament to the direction Pavement would take than that of the Jews, but, nevertheless, it stands as a great song in itself and a glimpse into the period when the band was still experimenting to find its own distinct voice. —Jack Meyer

13. “Snow Is Falling In Manhattan”

There’s no debate as to which 2019 song is the best and truest NYC ballad. It hits different after David Berman’s death last summer, but it maintains the dark, mystical beauty that simmered up the first time I heard it on a sweltering day in July. Hearing Berman’s lyrical poetry is nothing new, but there’s something so special about this particular description of New York. It works almost like an antithesis to Mitchell’s “Chelsea Morning.” Her NYC scene was a bright, light spring morning; his, a dark, cozy winter’s night. “Snow is falling in Manhattan / In a slow diagonal fashion / On the Sabbath, as it happens,” he sings. Then, later, the location becomes even more exact as the borough count rises to four: “Coming down in smithereens / On Staten Island, Bronx and Queens / It’s blanketing the city streets.” But he’s safe inside, with a “fire crackling.” And what a comforting vision that is, especially now. —Ellen Johnson

12. “We Could Be Looking For The Same Thing”

The last Silver Jews track before Berman entered over 10 years of radio silence, “We Could Be Looking For The Same Thing” pulls all types of heartstrings with the delicate duet between David and Cassie Berman. Berman’s music plunges the depths of loneliness so often that it’s refreshing to hear him assert that no matter where someone is in their life, someone else is always out there looking for the same thing. Maybe that sort of pragmatism is anti-romantic, but it’s still comforting to know that people, for the most part, will always need other people. —Jack Meyer

11. “People”

“People” is one of the jammier cuts from American Water. Stephen Malkmus uses his playful wah-wah tendencies to full effect over Berman’s breezy portrait of life. It’s the band’s idiosyncratic take on the country mentality of employing stock portraits of tiny pleasures (rainbows in garden hoses, sunny and 75 degree days), and throwing out Wittgenstenian lines like “The meaning of the world lies outside the world.” It’s a gentle reminder that remaining interested in the world around us, whether that’s staring out into space or at an unpainted ceiling, makes up a vital part of what being a person is. —Jack Meyer

10. “How to Rent a Room”

Around 2009, Berman had a confession to make. On a Silver Jews forum, he made two posts, the first announcing that the band was calling it quits, and the second, titled “My Father, My Attack Dog,” revealing what Berman described as “Worse than suicide, worse than crack addiction: My father.” He disclosed that Richard Berman—a notorious lobbyist responsible for dismantling unions, combatting minimum-wage increases and discrediting organizations dedicated to fighting everything from environmental protection to drunk driving—was his father. Berman said within the post that part of what drove him to form Silver Jews, before finally driving him to end it, was the hope of being a force that could amend some part of his father’s damage. He may have come to believe that art couldn’t do enough, but it doesn’t erase the seething vitriol that retrospectively pours from songs like “How To Rent a Room.” It’s one of the more haunting tunes in Berman’s discography, capturing the complexity of both his relationship to his father and his relationship to himself in light of it, ending with this chilling line: “Life should mean a lot less than this.” —Jack Meyer

9. “Nights That Won’t Happen”

Most of the tracks on Purple Mountains are painful to listen to in light of Berman’s death, possibly none more so than “Nights That Won’t Happen.” The song reads so much like a foreshadowing, opening with the line, “The dead know what they’re doing when they leave this world behind.” Berman led a hard, lonely life, and he poured that heartache into his music, but it was more than a well-crafted spectacle of suffering. This song stares right into the bare pain of existing in the world and rails against it, not necessarily in anger, but in an attempt to emphasize the pockets of empathy and acceptance that remind us, “When the dying’s finally done and the suffering subsides / All the suffering gets done by the ones we leave behind.” The presence of that void, of acknowledging all the nights that won’t happen, doesn’t end in grieving over them; it ends in holding out hope for all the nights that still could. —Jack Meyer

8. “The Wild Kindness”

In spite of its title, “The Wild Kindness” opens with menacing reverb to deliver one of the more defiant songs in Silver Jews’ discography. The lyrics mix around the mythic and quotidian, with dogs that stand for kindnesses and silences, motel “voids,” and Manets described as “Oil paintings of X-rated picnics.” As the value of everything melds together into an ambiguous soup, the narrator seems to toe the line between self-abdication and self-annihilation, before reaching a final resolution to continue on, if for nothing else, to “hold the world to its word” in one of the closest things to a Silver Jews anthem. —Jack Meyer

7. “There Is A Place”

Tanglewood Numbers marked a decisive turn in the sound of Silver Jews. The subdued, mid-tempo alt-country that defined most of their first four albums took a backseat to a larger sound, with a huge list of rotating personnel on the album that brought Malkmus and Nastanovich back into the mix alongside the talents of Will Oldham, William Tyler, Berman’s wife Cassie Berman and others. Nowhere is the sound bigger than on the album’s barnburning closer, “There Is A Place.” It’s difficult not to read the song in light of the change in Berman’s life between the recording of Bright Flight and Tanglewood Numbers. In 2003, he’d attempted suicide through an overdose, only narrowly surviving through the intervention of his wife. After a bout of solipsism following his near death, Berman found himself turning seriously to Judaism for the first time in his life. In one of his last interviews, he described his period of religiousness, saying, “One thing that just seemed absolutely clear to me was that everything was unraveling, and that we were losing the last generations of people who knew how to work the country and knew how to work the institutions.” That sense of prophetic confidence, wisdom and dread explode out of the music as Berman shifts from fearful recollection of a place beyond the blues to manic affirmations of “I saw God’s shadow on this world.” he tempo, noise, aggression and all-around sonic density boil to a fever pitch as it fittingly caps off the loudest of Berman’s musical statements. —Jack Meyer

6. “Advice To The Graduate”

The Silver Jews’ origin goes back to the University of Virginia, where founding members and then-students Berman, Malkmus and Nastanovich (along with Yo La Tengo’s James McNew, because why not) played together in the noisy college-rock project Ectoslavia. It’s fitting, then, that one of their first great songs is about the disconnect a graduate feels between what people say to expect for life and how the real world really feels (bearing in mind that Berman, Malkmus and Nastanovich would’ve been splitting a Hoboken apartment while daylighting as security guards and bus drivers around the song’s time of writing). It’s also just a jam with great chemistry between Berman and Malkmus, with loose guitar work that recalls the stronger parts of Slanted and Enchanted-era Pavement. —Jack Meyer

5. “I’m Getting Back Into Getting Back Into You”

The texture of this song is almost as heartbreakingly gorgeous as Berman’s lyrics on it. Lap-and-steel guitar, subtle theremin wobbles and lush backing vocals hit just the right note to draw out the offhand loneliness when Berman says “I’ve been working at the airport bar, it’s like Christmas in a submarine.” The song, as do many of Berman’s, picks up from the already down-and-out as Berman tries making it up to some flame he’s left behind only to find himself drawn back. With few words, it glides between the strangeness of falling out of love and the sentimental warmth of falling right back in. Whether that juxtaposition fills you with hope or dread is up to you. —Jack Meyer

4. “Black and Brown Blues”

Berman’s music has an uncanny knack for being able to say so much without really saying much. “Black and Brown Blues” literally follows the singer as he chooses between putting on a pair of black or brown shoes, and in that moment of reflection, conjures images of kings trapped in golden rooms, jaded skylines of car keys and corduroy suits made of a hundred rain gutters. These are some of Berman’s most evocative lyrics, all pouring out over the simple decision to make any decision at all. —Jack Meyer

3. “I Remember Me”

There are whiffs of narrative in Berman’s music, but most of it rests in an abstract, internal space. Then there’s “I Remember Me.” Through five-and-a-half minutes, it charts in painstaking, country-esque detail a ballad of two people falling in love. But right when the man gets on his knee to propose, he’s hit by a runaway truck. Waking from a coma years later, he finds his love’s married a banker in Oklahoma and, stuck on the land he’s bought with his settlement, feeling the metal of the truck that tore him from his dreams, remembers the people they once were. It’s a brutal distillation of how it feels like to live in the past and a standout among the almost categorically bleak tracks on Bright Flight. —Jack Meyer

2. “Trains Across The Sea”

Berman said that “Trains Across The Sea” was the first real song he wrote. If that’s true, it was a hell of a start. Musically, the song’s about as simple as they come: two chords, guitars, drums and just a sprinkle of keyboard. Berman’s lyrics and delivery is the glue that brings it all together. Wiser beyond his 27 years, he strikes a balance between world-weary, concerned, comforting, resilient and resigned, spewing one instantly quotable line after another. “Half hours on earth, what are they worth? I don’t know / In 27 years, I’ve drunk fifty thousand beers, and they just wash against me, like a sea into a pier.” These sort of lines, poetic without any pretense, cryptic enough not to mean anything in particular but moving enough to mean something to anyone, are the Silver Jews at their most potent and Berman at his most irreplaceable. —Jack Meyer

1. “Random Rules”

“In 1984, I was hospitalized for approaching perfection,” Berman says, adding to his vast repertoire of unforgettable opening lines. What proceeds from there is not so much a sketch as a world in miniature, touching on love, time, loss and the general chaos of being a living, changing thing in a world changing at the same time. Buffeted with melancholy horns, Berman’s wry delivery becomes both terrifying and comforting, a reminder of the randomness that prevails in our lives as well as a guide toward accepting it. —Jack Meyer