When British newcomer Sam Fender exploded onto the pop scene in 2019, the impact felt almost meteoric. Rarely does an untested young talent fall to Earth so fully formed, so unusually self-assured, and confident in sound, vision and conceptual delivery—he was simply born to be a rock star. And he reaffirms that status on his new Seventeen Going Under magnum opus, which shatters musicians’ dreaded sophomore jinx into benign shards.

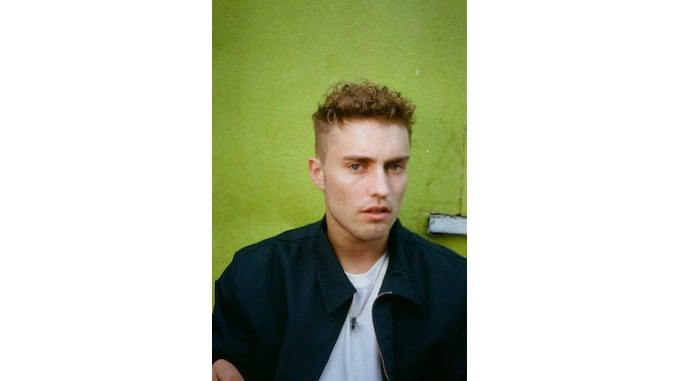

Even before you heard the stunning compositions of Fender’s brash, swaggering debut disc from that year, Hypersonic Missiles, that Next Big Thing cachet was immediately evident in its haunting cover photo. The kid’s brooding charisma beams laser-like from beneath his mop-topped, heavy-lidded brow, as he glares with a certain Robert Pattinson aloofness—a photogenic look that’s been winning the 6’1” part-time thespian U.K. TV roles since childhood. And that’s just the surface—the music inside did not disappoint. In fact, it was something of a revelation, and easily a 2019 standout.

The number Fender chose to open that treatise, the title track itself, was telling, and it set the socio-political pace for everything that followed. It kicked off with a gently clucking guitar riff and his marbled murmur—every bit as arresting and charismatic as Tom Petty’s was on his eponymous 1976 debut with The Heartbreakers—then waded right into some heady lyrical territory about rampant globalization: “Dutch kids huff balloons in the parking lot / The Golden Arches illuminate the business park / I eat myself to death, feed the corporate machine / I watch the movies, recite every line unseen / God bless America and all of its allies / I’m not the first to live with wool over my eyes.” And when Fender’s voice soared operatically—and angrily—on the clanging chorus, you soared with him: “All the silver-tongued suits and cartoons that rule my world / Are saying it’s a high time for hypersonic missiles / When the bombs drop, darlin’, can you say that you’ve lived your life?” And that was just his first salvo, with “darlin’” being a nod to the common-man vernacular of his songwriting idol, Bruce Springsteen. The album just got better, more and more majestic, from there.

“Hypersonic Missiles” was followed by a charging “Borders” (the set’s sole childhood reflection), then a Sprechgesang, self-recriminating chimer called “White Privilege.” But once it started galloping, through a finger-popping “Play God,” a jangling “You’re Not the Only One,” the R&B-slinky “Saturday” and the pulse-pounding perfection of “Will We Talk?,” the record didn’t lose momentum. It helped that the artist was in the capable hands of producer Bramwell Bronte, who miked his subject with a cavalcade of isolation-tank reverb. And—following the old why-fix-it-if-it- ain’t-broke adage—Bronte returns to follow the same sonic strategy on Seventeen Going Under. But the show truly belongs to Fender, who mans an arsenal of instruments this time, playing everything from bass, piano, and guitar to Hammond organ, Fender Rhodes, harmonica, mandolin, glockenspiel and synthesizer.

Some artists found the pandemic and its attendant lockdown oppressive. Fender did, as well, but he used the downtime to his advantage, digging deep into teenage reflections while trying to make sense of his tumultuous life, which began in North Shields, and was shaped by the advanced musical taste of his brother Liam (10 years his senior; he turned him onto Bruce) and events like his mother Shirley leaving when he was eight, his stepmother later kicking him out of his father Alan’s house at a crucial 17, and he and his mom reconnecting thereafter. Listening to his remarkably assured delivery—which was discovered by Ben Howard’s manager when Fender was performing in a pub in 2013—it’s sometimes hard to believe that Fender is only 27. But he sounds like he’s been around forever on Seventeen, which also opens on a novel title track, a ching-chinging youthful reflection with no specific chorus that romanticizes what were obviously some very dark times. By the second song, the aptly dubbed “Gettin’ Started,” the vocalist is firing on all six, and ready to experiment with “Aye” (which melds handclap percussion with fly-buzzing guitar), a climate-change-conscious tumbler, “Long Way Off,” the oblique-chorded punk piledriver “The Leveller,” a current folk-rock single called “Spit of You,” the monolithic keyboard ballad “The Last to Make it Home” and his gentle rundown of essential hard-won wisdom, “Mantra.” Technically, the disc closes on the decidedly Springsteen-esque “The Dying Light,” which finds him drowning his sorrows at a dingy bar alongside all the other disappointed, dead-end, on-the-dole locals. But the album’s deluxe edition—highly recommended, considering Fender’s top-tier compositional caliber—features five bonus cuts, including “Better of Me” (which explains how therapy session opened up the Pandora’s box of observations that grew into this collection) and the piano-dirge coda “Poltergeists,” wherein Fender laments, “I haven’t been the best of men / Morality is an evolving thing … This place is full of poltergeists / And tonight I’ll join them when I die.” Not exactly the uplifting last words you want to hear from your favorite songwriter at the end of their latest recording.

But Fender is not your average rock idol. He’s anything but predictable, and has already displayed the determination and remarkable breadth of vision that guarantee him longevity, true staying power that’s all too ephemeral in this disposable-pop-culture era. Brace yourself—this guy is going to be around for a very long time. And given just how good he is now, he’s only going to get better. He spoke to Paste about what it all means.

Paste: First, let’s address the elephant in the room—have you considered combining this album with songs from your debut and staging it as an American Idiot-auspicious musical?

Sam Fender: What—my album? Really? You reckon? I’ve never, ever thought about it. But I dunno if I’m at the stage in my career where I could actually do that. And I would have to get a really good script for the story, though.

Paste: Have you accepted any recent acting roles?

Fender: Not really. But that’s probably because I haven’t been trying to do it. But I might potentially do it at some point down the line—I am thinking about it. But I kind of wanna stick to getting a few good albums out first, you know? Because I’m really versed in the songs at the moment, and I’m really writing a lot right now. I wrote 60 songs for this album, and I picked 11 for Seventeen Going Under, 17 on the deluxe version. And then there’s a boatload of other songs that didn’t make the cut, and some of them I’m really excited about, but I’m begrudgingly holding them back for a while. Because I really do like some of the ones that didn’t make it onto this album.

Paste: Correct me if I’m wrong. But early in the pandemic, didn’t you do a live-streamed Zoom broadcast where you muffed the lyrics to Springsteen’s “Reason to Believe”?

Fender: I know! I just got so nervous! It was quite nerve-wracking doing a live broadcast when you’re just going out to fans. I find it a bit more threatening than an actual show where you can see people, because at least you can see people reacting to the song. But when it’s just you on your own? I mean, we raised £10,000 for charity just doing that 25-minute set online, so there were obviously a ton of people watching. But it scared the shit outta me, as well, because you didn’t really know if they were into it or not, or whatever. I found it quite nerve-wracking because you had nothing to go off of—you’ve just got your little phone screen to look at. It was weird.

Paste: Now the big post-pandemic problem is, artists have gotten so accustomed to concert streaming that they’ve forgotten how to banter with the audience.

Fender: I know! And I was actually fucking trying to learn how to sing again! My voice was going out, and it was crazy, you know? Because I used to sing every fucking day—you sing every day when you’re at it, working—and then we had a whole year off of just sitting in the house, writing. And I was singing in the studio, and I was so happy with how my voice was sounding. But going back to playing live, it’s a different beast, you know? So it’s like you’re learning how to pace yourself and not go crazy all the time, because a lot of times it’s just so tempting to just go out there and fucking throw everything at it, like you would do if you were in the studio. But then you’ve really got to reserve some, so I feel like I’m just learning how to do my job again. It’s bizarre.

Paste: Were there any times during the pandemic when you were actually scared?

Fender: Early on, yeah. Because I had a shielding letter from the NHS, the Health Service, saying that I wasn’t allowed to leave the house, due to my health condition that I have, because I was more likely to get ill. I’ve got a compromised immune system, and it’s because of a health condition which I haven’t spoken about yet, but I might do down the line. It’s one of those health issues that, when you read it on paper, people probably just immediately assume that I’m a goner. It’s quite a scary thing, and something that you really don’t want, but it’s something that I manage, you know? But it leaves me at risk for things like Covid, so for the first three months, I was pretty fucking scared, and I wasn’t allowed to leave the house, and there’s nobody who lives with me. So I was completely all alone for three months, and that was pretty fucking scary. And I’m in Newcastle, my dad lives in France, and my mom lives in Scotland, so I don’t see my parents very often.

Paste: So how did you get food?

Fender: I got friends to deliver it! They’d drop by and leave food for me at the door. And I had a lot of friends bring me Pepe’s Chicken. Not Popeye’s—it’s Pepe’s, and Pepe’s is different. Have you heard of Nando’s in England? There’s another chicken place called Nando’s, but Pepe’s is like the poor man’s version of Nando’s, and I think it tastes a lot better. So that helped me through the lockdown.

Paste: There were some days when I felt like Keanu’s Neo character in The Matrix, when they finally track down his physical form. He’s just a slime-pod battery, with no hope for tomorrow, powering this gray, oppressive, dystopian machine.

Fender: That is a great analogy. And I think a lot of people felt like that. But I was thankful that I wasn’t stuck financially, as I think a lot of people are. A lot of my friends lost their jobs, and some were left displaced by the rules and the furlough schemes over here. So some people lost their jobs completely, and some people’s businesses went to shit—it was a fucking nightmare. So I was always thankful knowing that at least one day I would return to do my stuff. But I didn’t handle it very well. But I do think I handled it just about as well as anyone else, although I drank a lot more than I should have and I didn’t really look after myself, didn’t go to the gym, didn’t really go anywhere—I just sort of played videogames and ate chicken burgers.

Paste: When did you finally regain your balance?

Fender: I think when I started getting deep into the recording of the second album. Once we went to Ireland to record some of the album, I felt like that was quite special, because some of my mom’s family came from that way, and I’d never really spent any time in Ireland. So it was quite nice to go out there and just have a bit of solace, and have a bit of time away from just listening to the news about the pandemic. So just to focus on the music? I was really grateful for that. And that turned everything around, I think.

<b?paste>: It’s always amazing when an artist aims high. You not only wanted to make your own Born to Run, you also close it out on Track 11 with your own “Jungleland,” the huge anthem “The Dying Light.”

Fender: Ha! Yeah! And it’s definitely not as good as “Jungleland,” and it’s not as complicated. But I definitely, definitely tried to have a bit of a “Jungleland” feel there, 1,000%.

Paste: And just like Springsteen, you’ve now got your very own Clarence Clemons—a full-time sax player in the band, who really gets to wail on these tracks.

Fender: Yeah! And Johnny Davis is one of my childhood best friends. He’s actually one of my brother’s friends, and my brother is older than me, so I grew up watching Johnny’s band, thinking he was the coolest guy, ever. He’s been doing the same thing since 2001. And this is a good story for you—he went to see The Blues Brothers when he was a kid, and he saw them play a live gig. And “Blue Lou’ Marini, the sax player from The Blues Brothers, met him afterwards and actually gave Johnny a saxophone lesson. And then when he was older, Johnny saw Blue Lou in Ronnie Scott’s in London, the jazz club, and Blue Lou remembered him and then invited him to come to New York. He said, “Why don’t you come over to New York and spend a bit of time with us? Come to New York and play some of the clubs out there!” So then Johnny went and stayed in New York for three months with Blue Lou, and learned loads of tricks of the trade from one of the most legendary sax players on the New York scene. And since then, we’ve decided that we’re gonna go and do the third album in New York come January. So I’m actually going to move to New York in January, I think, me and the whole band. We’re gonna go out there and write and record the third record, which I think will be great.

Paste: You’ve already mastered your craft to the point where you no longer rely on simple verse-verse-chorus-bridge-verse schematics. Sometimes, you just let a good tune build and build to a huge crescendo.

Fender: Yes. And there’s a lot of that on this album. A lot of different flavors, too. The opening track, “Seventeen Going Under,” is just a story song, and “Aye” is just a rant. And “Mantra” is just three verses and a trumpet solo, and then a guitar solo. There are lots of horns on this, a lot of horn parts and a lot of string parts.

Paste: There’s a lot of lyrical wisdom here, too. As on “Mantra,” where you caution yourself to “stop trying to impress people who don’t care about you.”

Fender: Yes. And as I say in the song, “I’ve known it for so long.” I’ve spent a lot of time trying to suffer fools and sycophants, and people who really weren’t very good for me, I suppose. And now I’m trying my best to kind of vet that out of my life. But I think it’s just a part of growing up, really. So I’ve learned that you’re always learning. And that the studio time is the time for me to really explore and get a lot more confident, which is what I did on this record, I think. I was a lot more confident with this one, like when it came to writing string parts—I wrote all those parts on this album, so this is really my baby. I mean, I don’t play all the parts because I can’t play all of them, but I wrote all of the parts with guitar or just my voice, you know? Or with the piano. And I play the piano a lot on this record, especially on “The Dying Light” and all of that.

Paste: Some of the piano-based material even sounds like vintage Elton John.

Fender: Yeah. Totally. And Elton is now actually a friend. So I’ve been hanging out with him and learning some of his tricks. He’s a legend. We were going to do something for his Lockdown Sessions album, but I needed to stay focused on what I was finishing. And we didn’t want to rush it or fuck it up. So I hope we can return to it down the line or drop in on it later.

Paste: What, exactly, is “The Leveller” about?

Fender: It’s kind of about two things. It was at the beginning of the lockdown when I wrote it, and I was in a place of real … I was just really down at the time, and a lot of big changes had happened. My grandmother had just passed away, and she was kind of like the glue that kept our family together for a lot of years. And I guess I was quite scared of my illness that I have, so I suffered health anxiety with my condition that I got when I was 20, and that started coming back, simply because I wasn’t so busy. And I have always been busy. So busy that I’ve never had time to worry about it, you know? But all that quiet time made me regress back into my fear, into my fear of death. So it’s kind of all about that, but also about how I wasn’t defeated. It was dark, and I was quite depressed, but I wasn’t defeated. I was quite angry at the time, actually.

Paste: When you decided to go back and explore your childhood with Seventeen, did you have old diaries or journals to refer to?

Fender: Well, the time-traveling thing came because I started doing therapy. I’d started doing therapy, and my therapist is kind of Freudian, and he made me think about my childhood, you know? He made me talk about growing up, and all the insane moments in your past that you initially pass off as insignificant things. But they actually were pretty significant. One of them being the time when I was 17, and my mother was suffering from fibromyalgia and mental health issues. And she was unemployed, and I was unemployed because I was only 17 and in the equivalent of senior high, and she was being taken to court but the DWP—the Department of Working Pensions—who were basically trying to put her back to work, when she wasn’t fit to work. And bear in mind that this was a woman who was a nurse for 40 years, and she never missed a day of work in her life—she was a real hard worker. But because she got ill, just to watch the way that the government trapped my mother was terrible. She had to go to court on three separate occasions, which inevitably made her a lot more ill, and a lot more depressed. So it was just me and her, and we couldn’t really afford our rent, and everything was going to shit and we were always skint. And she was always in tears and fumbling to follow these court matters, and she just wasn’t herself. And I was old enough to back her up, but I was too young to be able to help her financially. So there was a level of shame that came with that. It was a strange time, but it was character-building. And my parents split up when I was younger, and so my mother and I always had a strange relationship—she’s kind of like my best mate, in a way. So that was great in some senses. But in other senses, it wasn’t exactly what I’ve always needed, to be honest with you. But therapy kind of opened up all this stuff, and gave me all this stuff to write about. And I was always in fear of writing about my personal life, but the pandemic unlocked a door on my creative writing, and then therapy helped me recall memories that I didn’t know were there. And there was so much stuff that I worked through that I didn’t even realize had affected my self-esteem, and affected the person I am now, you know? So the therapy has been very strange, and it’s been quite painful, as well. It’s a tough thing to do, because you’re exhuming stuff that you’ve consciously not really properly delved into, or not been able to understand previously. So you’ve kind of emotionally shut down, you know? And there are songs on the deluxe edition, as well, like “Angel in Lothian,” that are about that early time. And it’s a real heartland rock song, for want of a better term. But I prefer this record. I’m more proud of this record than I am of the first one, because it took a lot more work. But it was a lot more personal, you know? And that’s been a learning curve in itself. But there are moments of clarity, where I feel like I actually deserve to do my job.

Paste: “Aye” lists a lot of things that piss you off. And you’d think humanity would have learned some graciousness from the pandemic. But no, here in America, the far right is busy chiseling away at women’s rights, Black voters’ rights, human rights in general, all in the name of winning the next election, while ignoring the climate change that will literally doom us all.

Fender: Yes. And we’re running out of time. We are truly running out of time. And “Aye” came from that concept of those people out there who are so rich, and they watch what happens throughout history while managing to remain completely anonymous. And it’s not just some stoner conspiracy, not just about the Illuminati. It’s about those old-money billionaires who control so much wealth on this planet. I saw my mother struggle fucking horrendously, and I saw loads of my friends and people in my family struggle. There was real poverty in the neighborhood that I lived in, and there was real poverty in arguably one of the richest countries in the world. And I’m like, “How in the fuck can we have that and then have all these people who are living on their private islands, and they’ve got all these hedge funds and their money’s all tucked away in these private accounts?” That song came from that, but it’s also about the fact that the underlying premise of the left wing, I find, is so out of touch with working-class people that it alienates them, especially here in England at the moment. There’s a feeling now that left-wing politics is some snobby middle-class thing, and it’s bizarre. Up here, where I live, it’s one of the places that voted Tory this time. And it’s never, ever voted Conservative since its inception—it’s a shipbuilding town, a working-class town, and I’m left wing as fuck. But now people around here are like, “Ah, you’re a lefty! You’re a fucking lefty!” It’s just insane. I feel like the left are so preoccupied with their culture wars, and obviously a lot of those things are completely valid. But I genuinely believe that if we focused on class, and just the disparity between wealth and poverty in general, then a lot of these other problems would start to fix themselves. Because working-class people should not be living in poverty.

Paste: Feeling grateful is a good way to go through life.

Fender: 100%. I agree, 100%. And I’m very grateful about where I am right now, for sure. I’ve got my own place now, and once I sign my next lot of publishing deals, I think I’m gonna try to get my mom a place, as well … And if I can get my mother a place where she can finally put her feet up? Well, then that will be my mission accomplished, you know?