At the time when the “Peace and Love” sloganeering of the hippie dream started to reek of good intentions baking underneath the sun in the gutters of Haight-Ashbury, the young composer and songwriter Randy Newman was ready for a heel turn. On his third album Sail Away—which celebrates its 50th anniversary today, May 23—he delivered a timeless opus full of masterfully deceptive songs that play out like a collection of standards for the ugly moments in human history that pop music wasn’t willing to touch in the past.

Like any good saboteur, Newman took some time to learn the blueprint of the machine before he set about dismantling it. At the outset of his career, with two quietly acclaimed albums under his belt, Newman’s approach was not so dissimilar to in-demand pop writers of his era like Jimmy Webb or even Burt Bacharach. That workman-like approach to writing and composing was ingrained somewhere deep in his bones, as he was born into a deep lineage of Hollywood film composers. His uncles Alfred Newman, Emil Newman and Lionel Newman were all in the business—with the latter winning an Oscar for his work on the Barbra Streisand-starring film adaptation of Hello Dolly in 1969. He has spoken often about his admiration of alumni of the Tin Pan Alley songwriting machine, like George Gershwin. He could have made an admirable career out of writing made-to-order clones of string-laden piano ballads like “I Thinking It’s Going to Rain Today” and “Living Without You,” which occupied his 1968 self-titled debut album, for swingin’ crooners to stuff onto their albums. But Newman realized that was a dead end for him in a creative sense.

“I’ve often wondered if I’d have kept going in that direction, accompanying myself with an orchestra and taking things apart, what I’d have been,” he told Vanity Fair in 2016. “I think I’d have been interesting, right? But I don’t know whether anyone would have subsidized me, or found me as interesting as I did.”

Newman shook that expectation off his collar with his more rock-oriented 1970 follow-up, 12 Songs. It was a move that was applauded by critics, including Robert Christgau of the Village Voice, who gave the album an A+ rating. In his review, Christgau hailed the album as Newman’s arrival as a master of toeing the line, both musically and lyrically. “Newman’s music counterposes his indolent drawl—the voice of a Jewish kid from L.A. who grew up on Fats Domino—against an array of instrumental settings that on this record range from rock to bottleneck to various shades of jazz,” he wrote in 1970, “and because his lyrics abjure metaphor and his music recalls commonplaces without repeating them, he can get away with the kind of calculated effects that destroy more straightforward meaning-mongers. A perfect album.”

But as many now know him best for his hired-gun work on film scores and original music for Pixar films, Newman never fully rebuked that avenue. The longing to be tapped for the gig hasn’t left his work ethic in the past five decades. Much like Tin Pan Alley writer-turned-shit-stirrer Cole Porter, Newman wanted to meld his mastery of melodic and lyrical economics into a Trojan horse that could send a shiver down the spines of the squares of the old guard, as well as the self-policing radicals of the Woodstock generation who were up the creek without a paddle at the start of a new decade. When he was compiling the material for Sail Away, he even wrote a song intended for Frank Sinatra titled “Lonely at the Top.” The song’s lyrics were intended for only someone as ubiquitous in pop culture as Franky Blue Eyes to sing, as it takes aim at the woes of a listless icon who has reached a level of boredom and loneliness that only he could understand. “I’ve been around the world / Had my pick of any girl / You’d think I’d be happy / But I’m not,” the song goes.

Sinatra passed on the song. Maybe he could see the vitriol that Newman had for celebrity, or maybe he just didn’t like the tune. It’s a question that Newman grappled with in discussion with Rolling Stone’s David Fricke in 2017.

“There was a massive drive at Warner Bros. Records to get Frank a hit,” he said. “I thought—maybe stupidly—that he would be ready to make fun of that leaning-against-the-lamp-post shit: ‘Oh, I’m so lonely and miserable and the biggest singer in the world.’ I never bought that part of him. I thought he’d appreciate that. I played it for him, at his office on the Warner Bros. lot. His reaction? Nothing. He said, ‘Next.’ I also played ‘I Think It’s Going to Rain Today.’ He said, ‘I like that one.’ But he couldn’t hide his bitterness at young people’s music.”

The song made it onto the tracklist of Sail Away instead, and has since become one of Newman’s better-known songs for its ability to seem like a song that predated the vapidness of celebrity culture while also being distinctly of its time. You could see its commentary play out both in the decades that preceded it and up to today, as there has been no shortage of tragically disillusioned stars whose fame catapulted them away from ever being able to relate to normal people’s problems. This astute sense of social commentary found its footing within Newman’s writing on Sail Away. From then on, the world was in his crosshairs.

The album’s opening title track could be pinpointed as the moment where Newman found his true artistic voice as a songwriter. Though his writing on 12 Songs had elements of the twisted perspective for which he is now known, he had never thrown his professional life on the line in pursuit of a gut-punch quite like this. The song’s narrator is an American invader giving his best sales pitch for how much better the lives of his African prisoners will be after he loads them onto his boat and sails back to the port of Charleston Bay in South Carolina. He offers his own experiences back home to dismiss any of their fears by promising they’d get to “sing about Jesus and drink wine all day,” with no threat of jungle cats or mamba snakes jumping out of the bushes to get them. There’s no way in hell that these people were not violently forced into bondage against their will, but Newman’s character appears to be acting as a harbinger of good faith.

The kicker is that he’s burying the lede. The man never comes out and says that these people will be sold into slavery upon their arrival, and that’s part of Newman’s genius. He wants us to finish the equation that the song presents, to picture the evil that is in store once they make it back to shore. Even the line where Newman’s character says that “everybody is as happy as a man can be” may seem like a tossed-off lyric, but his choice to use “man” instead of choosing a more inclusive pronoun only signifies that things back at home might not be great for women, either. But how would that character know that what he was doing wasn’t some sort of preordained right at that given point in history? He was just following orders from God and country. In fact, the only actual evidence of force within the captor’s spiel comes in the song’s final verse, where he leaves no room for argument or choice. “You’re all gonna be an American,” he sings. “Sail Away” introduces a perspective that many of Newman’s peers may have been too scared to present. He doesn’t obscure the message with poetry. Instead, he speaks plainly while tracing the white savior complex back to its original evil marketing strategy. Wouldn’t you be better off imprisoned in America than free in the third world?

Elsewhere on the album’s first side, he introduces a fawning prayer to a hidden God watching over us with “He Gives Us All His Love” (more on that later) and the genuinely pure-of-heart “Simon Smith and the Amazing Dancing Bear.” Given how biting his tongue had been earlier, it’s almost alarming how the jaunty piano jingle about a boy and a bear dancing for wealthy folks at a local fair never really stretches outside of a G rating. The song had been a hit for English singer Alan Price in 1967, which explains its relatively tame commentary on the class divide in America. Sandwiched in between is the rocker “Last Night I Had a Dream.” Newman’s recollection of a hyper-specific nightmare he had is aided by a funky rhythm section that included legendary drummer Jim Keltner and slide guitar from Ry Cooder, who first played on 12 Songs and would remain a frequent collaborator of Newman’s throughout his career. Even though Newman runs into both a ghost and a vampire while floating through his dreams, what causes him to panic is that the love of his life can’t even remember his name. Even worse, a small crowd around them is there to point and laugh. It’s a mortifying miscommunication, and offers a glimpse into Newman’s fragile sense of self-worth. In just a few paranoid lines, Newman was presenting the antithesis of Mick Jagger’s horned-up prowess.

The song “Old Man” is the most surface-level tearjerker that Newman pens on the album, and one of its most criminally underrated moments of brilliance. The story depicts a boy at the bedside of his dying father. He offers to quell his father’s confusion as he drifts in and out of consciousness, telling him that even though “everyone has gone away,” he’ll make sure to stay by his side as he nears the end. With its grand, sweeping orchestral arrangement and gentle piano chords, it seems like a song destined to be played to alleviate moments of profound sorrow. But underneath the lush strings and the boy’s initial loving moments with his father, we begin to feel something is rotten at the center of this family dynamic. We learn, as his son tries to get his father to focus in his weary state—”Can you hear me?”—that no one else actually came to visit him. Even the sun and the birds have disappeared somewhere beyond the clouds. The son pleads for his father to open his eyes and acknowledge his presence, and to get it through his head that his time as the patriarch is over. The future of the family legacy will live on after he is forgotten, because why would they need him around if his son is “just like” him?

Things get a little more fucked from there, as the song takes on a last-minute reveal worthy of an A24 psychological thriller. When the son mentions the fact that his father raised him to be a cynical atheist, he tells him that even if he has second thoughts about the whole religion thing, in his last breaths there will only be pain and then simply … nothing. “There won’t be no God to comfort you,” he says bluntly, “you told me not to believe that lie.” You can practically feel his frail father contorting in his hospital bed, finally giving himself over to fear in his final hour. But his son has been raised right, and by “right” I mean a stubborn, “free-thinking” contrarian in his father’s image. Some may call him an “asshole.” In his own way, he tries to calm his father down by explaining that there are no obligations anymore—”You don’t need anybody / Nobody needs you / Don’t cry old man, don’t cry.” As the strings fade, he tells his father to toughen up and stop crying because, honestly, this isn’t a special or unique moment. “Everybody dies,” he shrugs. The music stops as abruptly as a heart monitor no longer reading a pulse. The boy is left alone now to confront his father’s lifeless body. What was once a song about respecting elders and cherishing passed-on wisdom, Newman finds a twisted way to turn into a critique of cynicism and nihilism. There was nothing stopping the boy from comforting his father at the end of his life, but the urge to dismantle the idea of an afterlife was too strong for him to deny. Newman doesn’t tell us if the son will have visitors by his deathbed years down the line, but one can only assume his thick shell will never allow anyone to ever get that close. Most songwriters would find a way to right the ship and steer towards compassion. But Newman has never been afraid to amplify the darkness.

As we flip over to side B, it should be noted that the production and engineering team assembled by producers Lenny Waronker and Russ Titelman on Sail Away is simply immaculate. The personnel that Newman assembled fulfills his orchestral pop vision with a sense of naturalistic beauty without overcrowding the songs. In that regard, the album achieves a sonic high-water mark that could have easily stumbled into schlocky Engelbert Humperdinck territory in the wrong hands.

To open the next side, Newman fast-forwards his historical scope of American injustices to present-day foreign policy on the satirical masterwork “Political Science.” Over a vaudevillian can-can instrumental, Newman plays the part of a man in the upper echelons of command in our government with a foolproof plan to get our superpower of a nation out of its obligations and messy entanglements around the globe. Our “allies” make fun of us behind our backs, and those in need of a handout give us nothing but spite and hate in return. His solution: “Let’s drop the big one / and see what happens.”

The song then goes into a list of trivial reasons why we should nuke different cultures off the face of the Earth. What is so terrifying about the swift and barbaric armageddon in the name of a red, white and blue globe this character is proposing is that even though it sounds ridiculous, America has always been closer to going off the deep end than we care to admit. For chrissakes, we had a president who considered nuking hurricanes. Deep down, we’ve always been an easily chantable slogan away from becoming the villains in this story. Knowing the many nefarious things that happen due to our constant military presence around the world, maybe we already are.

On “Burn On,” Newman sings about the ecological disaster that is Cleveland, Ohio’s Cuyahoga River over a playful horn arrangement. Since 1868, the river has caught on fire over a dozen times as a result of the city routinely dumping industrial sludge into it. Newman juxtaposes the city’s gorgeous lights with the flames rising off the water, egging it to “burn on” in a way that makes it seem like these occurrences are a point of pride for the people who live there. In a sarcastic bit of marketing, he explains that the lord has the ability to change the current of the river, but can he make it burn? Back off, God! That’s a power only bestowed upon Clevelanders!

On one of the album’s most simplistic arrangements, “Memo to My Son,” Newman grapples with the self-centered disposition of his newborn child. Over a brisk folk-rock composition consisting of piano, drums, bass, acoustic guitar and accordion, Newman is at odds with a child unable to follow his instructions. “Wait’ll you learn how to talk, baby / I’ll show you how smart I am,” he says before rattling off a couple of cliched nuggets of wisdom. “A quitter never wins / A winner never quits / When the going gets tough / The tough get going,” he sings with nothing better to offer. Don’t worry Randy, you’ll have time to turn it around.

Next is “Dayton, Ohio – 1903,” one of Newman’s most recognizable studies in Rockwellian Americana. The sweet piano ditty paints a picture of a happy couple in the famously blue-collar town, welcoming a visitor over for tea and to spend a day back in an era where people were courteous and kind. Much like “Simon Smith and the Amazing Dancing Bear,” it’s a rare gentle moment on the record that doesn’t contain an ulterior motive. It was also recorded by Billy J. Kramer—another British pop star—one year before the release of Sail Away.

With American society, family and religion all on the table, Newman also finds the time to explore sexual power dynamics in the downright thirsty “You Can Leave Your Hat On.” Newman takes on the role of the dom in this scenario, commanding his sub to undress to his liking and move in when he tells her to. While Joe Cocker would later turn the song into a hit with a muscular reworking in the mid-80s, the drunkenly woozy pace on Newman’s original helps to emphasize the desperation in his character. While others may deride the way his characters show affection for each other, Newman wants you to believe that this kink is just as sacred as Sunday mass. “You give me reason to live,” he sweetly repeats just after he tells her to strip down to nothing, raise her arms up to the sky and “shake em.” It’s safe to say that he doesn’t mean her hands.

The album closes with “God’s Song (That’s Why I Love Mankind),” one of the harshest damnations of blind faith and the squabbling and sycophantic tendencies of the human race ever put to tape. In the minor-key solo piano number, Newman takes on the role of the all-powerful creator who, after years of fielding dire requests from his most devout disciples on Earth, has decided to finally level with them. After written agreements etched in tablets and in the pages of biblical texts giving his word he would intervene in times of trouble for those who honor him, the people need to know why he contradicts himself time and time again. A man named Seth raises his hand, wondering why “Cain slew Abel” and why, if the state of Israel was intended to grow in numbers, that he would allow any children to die. To that, God tells him it’s because humans are no different to him than any of the other insignificant forms of life on the planet. “Man means nothing, he means less to me / than the lowliest cactus flower / or the humblest yucca tree,” he says. But still, after all the pain humans endure, they chase every clue that leaves them stranded out in the desert and assign meaning where there isn’t any, all to justify their misfortune.

All of the leaders of different religions who have contorted themselves to carry out his commands to fit their needs eventually meet for a televised conference where they call on God to stop the plagues that ravage the Earth. They feel that the time has come for him to make good on his word. It’s the least he can do after years of continued faith. But what we don’t understand is that God’s way of returning the order of the world back to stasis is ripping it all up and starting again—just like how he casts the ugly temples we have erected in his honor back into the sea. What separates us from the unimportant vegetation he equated us to is that we can’t seem to find a way to be grateful for getting the opportunity to exist at all. He recoils in horror at the mess we’ve all made of the home he has given us, and laughs it up with his buddies in heaven when we have the gall to pray for salvation. Details can be missed even with round-the-clock surveillance, and it’s not his fuckin’ problem that we can’t tend our gardens or get along with each other. But even after mounting casualties and devastation, we keep coming back time after time, hoping for an answer. The lord can’t help but feel like the most popular girl at the dance after all of that attention.

“I burn down your cities, how blind you must be / I take from you your children and you say, ‘how blessed are we?’” he says, with a satisfied grin. “You all must be crazy to put your faith in me / That’s why I love mankind / You really need me.”

The way that Newman delivers those last two lines is as sobering as a shot of adrenaline to the heart. His main point here is that, from the beginning, we have used religion as a way to explain our continued obsolescence amidst a universe that keeps expanding and revealing new possibilities for existence. If there is a creator, do you think he would really take the time out of his busy schedule to tinker with an outdated model? Apple stopped making the iPod, after all.

Newman would build off of this groundbreaking showcase of his talents on later masterpieces like 1973’s Good Old Boys and his underrated 1999 album Bad Love. But with all of this talk about his abilities as a satirist, what makes Newman such an influential and often-imitated songwriting archetype is that he is funny as fuck. It’s not a grand leap to see the influence that this style of writing has had on someone like Father John Misty. His approach in talking about the rotten core of humanity in the emergence of the singularity on his opus Pure Comedy echoed Newman’s subtle wit and ability to don the mask of the unreliable narrator to prove an uncomfortable point. You could also trace Newman’s trapped-between-two-eras musicality as an influence on The Walkmen, as well as the solo work of both Hamilton Leithauser and Walter Martin. A song like the early Walkmen single “We’ve Been Had” could not have existed without Newman’s weary and realistic skepticism. In a recent episode of Tim Heidecker’s call-in show Office Hours, Newman joined as a special guest, and both Heidecker and the show’s other guest, Kurt Vile, proceeded to praise him for his genius and for influencing their own musical works.

Another quality that makes Newman’s songwriting so fascinating to so many—outside of the compositional characteristics—is how easily he is able to toe the line between offensive and profound. If a song like “Sail Away” were to come out today, it’s sad to think that the commentary itself might play second fiddle to a trending tweet missing the point he was trying to make entirely. He eventually ended up running into some controversy with his satirical hit “Short People” from the 1976 album Little Criminals, as many listeners couldn’t see past his ludicrous demonizations of height-challenged people to the larger point he was trying make about the silliness of bigotry based on physical attributes. If they thought that was bad, they should have heard his scathing and uncomfortable takedown of systemic racism, “Rednecks”—the opening cut from Good Old Boys—just two years earlier.

It was some smoke that almost derailed his entire career. “It became pretty obvious to me that—no matter how lofty my aims—what I had was a novelty,” he told Medium in 2011. “It was one of those hit records that actually makes you less popular.”

In the 50 years since Sail Away’s release, the reputation that Newman established on the album has in many ways been overshadowed by that particular song and, more justly, his award-winning career in film. But in revisiting the album now, you’ll hear his willingness and determination to drag the influence of the great American songbook through the muddy lens of pop and rock radio in a way that is almost as subversive as his deceptively acidic lyrics. It’s a groundbreaking achievement, as it’s hard to think of another artist of his generation who could be as easily mentioned in the same conversation as both Bob Dylan and Irving Berlin. Newman has soundtracked pivotal moments for generations that have come of age with his grand and emotional scores to family-friendly touchstones in cinema. But if you dig back to 1970, you’ll find a man ready to call bullshit on the very thought of a fairytale ending. His sly wit had always been the concealed dagger by his side on his earlier albums, but it wasn’t until Sail Away that Newman became one of music’s most astute breakers of bad news.

Pat King is a Philadelphia-based journalist and host of the In Conversation podcast at Ears to Feed. He releases his own music with his project Labrador and is a tireless show-goer and rock doc fanatic. He recently took up long-distance running, which he will not shut up about. You can follow him at @MrPatKing.

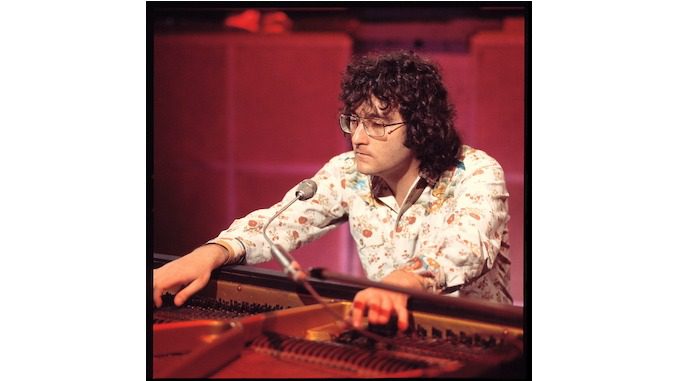

Listen to a 1983 Newman performance from the Paste archives below.