There aren’t enough guitar solos anymore. I mean, there are guitar solos still happening—in the metalspheres of the world, most explicitly—but rock and roll’s got a serious solo deficiency going on. Maybe I’m just talking about indie rock, since the most memorable guitar solo of the last ten years hit during the climax of Big Thief’s “Not” in 2019 (courtesy of the great Adrianne Lenker, who ranked #27 in our recent list of the greatest guitarists of the 21st century, by the way). Last summer, we got a really terrific solo from Sam Evian in Billie Marten’s “Leap Year.” But real shredding? That seems to be an endangered species—a relic lost to the Blog Era’s early 2010s fadeout.

So far we’ve talked a lot about guitarists, whether that’s me Lester Bangs-ifying Patrick Flegel, Cassidy Sollazzo walking down the paths of Joni Mitchell’s technique, Grant Sharples’ recounting of a Yasmin Williams concert, or Casey Epstein-Gross sharing with us the music that inspired her to pick up a guitar. And, we’ve ranked a lot of guitar stuff since last Monday. The fatigue is setting in, I’m sure, so I thought it would be a nice change of pace to poll some of Paste’s contributors—Casey and I included—about their favorite guitar solos. This isn’t a “greatest of all time” list, to be clear. It’s a mixtape, of sorts—a survey (roundtable via email?) of what this website’s writers like, rather than some kind of objective appraisal. I’ve gone ahead and made a TIDAL playlist of the songs mentioned in this article, which you can find here. These are the Paste cohort’s favorite guitar solos. Drop yours in the comments, we’d like to read about them. —Matt Mitchell

Casey Epstein-Gross, Associate Editor

Brian Eno: “Baby’s On Fire” (Robert Fripp)

I first heard Brian Eno’s surrealist masterpiece “Baby’s on Fire” as an actual baby, more or less: it was one of my parents’ household staples. For years I moved through life under the very confident impression that this bizarre art‑rock fever dream was universally beloved and playground‑famous (alas, my elementary school classmates were mostly just incredibly confused). The song itself is a nasty little loop: a tight hi-hat and bass line, cheap-sounding electronics skittering around the edges, Eno narrating a surreal photo shoot with a burning woman and a crowd of morons treating it like entertainment. But then King Crimson’s Robert Fripp’s guitar bursts in around the ninety-second mark, and all bets are off. He doesn’t so much solo as he does take over the song entirely: thin wires of feedback, shards of melody that never quite settle, notes that sound like they’re clawing to get out. For four manic minutes, the song becomes a feral, screaming power struggle between control and total collapse. Fripp reportedly laid the thing down after getting off a flight with the flu, which tracks; there’s a feverish, slightly delirious quality to the way the lines tangle and collide, as if he’s chasing ideas faster than his fingers can quite catch them. When the vocal finally staggers back in for the coda, Fripp doesn’t retreat so much as lurk: little spurts of noise keep jabbing at the corners of the mix, reminders that the fire never really got put out, just temporarily buried.

[embedded content]

Television: “Marquee Moon” (Richard Lloyd & Tom Verlaine)

“Marquee Moon” was my gateway drug into realizing guitar solos didn’t have to be macho peacocking or pure fuzz; they could be long, skinny, and weird and still feel absolutely gigantic. The track stretches past ten minutes—which, in the context of CBGB’s typical three‑chord pile‑ups, might as well have been Bitches Brew-length—and it spends nearly all of that time obsessing over two interlocking guitar voices. Verlaine lays down this clipped, see‑saw rhythm figure while Richard Lloyd threads dissonant little comments through the gaps, the two of them fitting together like a jigsaw puzzle. Lloyd gets first crack at a proper solo after the second chorus: a short, bright burst that feels carefully mapped, all melody and sharp edges. The real mind‑bender, though, is Verlaine’s long run after the third chorus, the one that gets likened to Jerry Garcia’s great wandering epiphanies. Over that same staccato two‑chord pulse, his guitar starts talking in this clean, almost austere tone, running up and down a scale, doubling back on itself, gnawing on the same shapes until they start to feel less like licks and more like thoughts he can’t quite shake. The band slowly cranks the temperature—bass and drums getting more frantic, chords climbing higher—until, around the 8.5‑minute mark, everything finally locks into this blinding, all‑hands‑on‑deck climax before they cool it off and stumble back into one last verse. It’s possibly the closest I’ve heard a song come to real-life hypnosis.

[embedded content]

Wilco: “Impossible Germany” (Nels Cline)

I know this is a list about the solos themselves, but you simply can’t talk about the “Impossible Germany” without first noting how much the song lulls you into a false sense of complacency. The first few minutes are all murmured melancholy and tasteful restraint; you could almost mistake it for a song you largely put on when in the mood to feel vaguely wistful. But from the second Nels Cline’s guitar kicks in right before the three-minute mark, the song begins to utterly transform. The tone is so clean it’s almost glassy, but he keeps nudging it into different shapes: a little sweet, a little searching, then suddenly knotty and insistent, like he’s testing how far he can lean before the song gives way. As Tweedy’s guitar starts braiding around him, it turns into this gorgeous multi-headed thing that lives somewhere between Allman Brothers‑style harmonies and Television’s wiry tangle, except filtered through Cline’s very specific brand of jazz‑nerd melodrama. There’s a reason it’s such a live show-stopper—seeing Wilco shred this one live borders on the sublime.

[embedded content]

Cassidy Sollazzo, Contributor

Allman Brothers Band: “Blue Sky” (Dickey Betts & Duane Allman)

Dean Ween refers to Dickey Betts and Duane Allman’s “Blue Sky” solos as the quintessential “happy” solo, and he’s right. It genuinely sounds like an open sky, all-consuming and massive, that unravels into a flurry of motion and feeling. The solo hits immediately and sits right at the front of the song, all backroads realism (sun shining, windows down, hair blowing, the works). It’s also among some of the last material Allman recorded in the studio before his death, which only sharpens the emotional pull and makes the brightness pack that much more of a punch. The bends linger, the slides glide just enough, and every phrase feels fully considered without ever sounding stiff. What truly elevates “Blue Sky,” though, is the interplay. Duane starts the solo section, Dickey creeps in beside him, and the two overlap and harmonize before separating again, this time Dickey taking the reins. Together, apart, together, they move like the literal soundwaves they’re producing, until they reunite at the end in those cascading sixteenth-note runs. Betts’s tone is slightly fuzzier against Duane’s clear, singular voice. The exchange feels conversational, generous, and balanced. It’s a true blueprint of tone, cadence, phrasing, and expression that fellow guitarists have been chasing ever since.

[embedded content]

Ethan Beck, Contributor

Midnight Movers: “Medicated Goo” (Charlie Pitts)

In 1969, Steve Windwood left Traffic, leading Island Records to scourge up odds and ends. They released a thumping, somewhat flat-footed outtake, with goofy character names like Pretty Polly Paulson and Freakin Fredy Frolly, as a Traffic single with little fanfare. But when Midnight Movers, Wilson Pickett’s backing band, recorded a rendition of “Medicated Goo,” it was an effortlessly light, funky addition to their first album, Do It In The Road. And guitarist Charlie Pitts saw an opportunity to turn this already souped-up version into a barnburner. When he hits the second guitar solo on “Medicated Goo,” his tone is so searing that it could be used as a paper shredder. Even though Pitts played on Issac Hayes’ “Theme from Shaft” and with other Stax artists, “Medicated Goo” is his finest moment.

[embedded content]

Neil Young & Crazy Horse: “Powderfinger” (Neil Young)

When Neil Young sings “Powderfinger,” he embodies a 22-year-old who’s struck with indecision as danger approaches. On the unbeatable Rust Never Sleeps rendition, Young’s first solo is forthright and cocky. He bends and contorts the strings as if he’s trying to get your attention, even if the upper echelon of his notes are awkwardly squeaked out. When Crazy Horse comes in on harmonized “oohs,” Young’s bend is so assured that it rings slightly false. And all of a sudden, we’re back to the song’s central riff. But when Uncle Neil returns to noodling on Old Black, everything about “Powderfinger” has shifted. We just heard that the narrator’s “face splashed in the sky,” a shocking, climactic act of violence that’s been looming throughout the entire song. Young’s second solo is more mournful, leaning into those wailed high notes, sometimes awkwardly strewn atop the chord progression. By the time he returns to those bends, they take on an elegiac, wrenching quality, as if he were looking for a way to explain the suffering that just took place.

[embedded content]

Pavement: “Fillmore Jive” (Stephen Malkmus)

Much has been made of Stephen Malkmus’ ability to tear a song apart, stopping the procession with his off-axis guitar work. His playing often strives to unveil the nightmare creeping underneath his moving madlibs. Just think of the soft, pushing guitars on “Fin,” which get crashed with an uncomfortable solo, all aching hammer-ons and dud notes. But he’s never finer than on “Fillmore Jive.” Malkmus’ first solo searches and plods along as if it’s walking home from the bar, comfortably drunk. But the next two solos are all pre-hangover headrush, embodying the tossing and turning required to crash after a long night out. Goodnight to the rock and roll era, indeed.

[embedded content]

The Pastels: “Nothing to Be Done” (John Hogarty)

Little prepares you for the surge of fuzz that twee rockers The Pastels toss onto “Nothing to Be Done.” After a few dueted verses and an invitation to “go and get a beer,” that sweet, slightly wobbly sense is “cut to shreds by brazen, bullying guitar solos,” as Karen Schoemer wrote in the New York Times when Sittin’ Pretty first arrived in 1989. You quickly understand why Teenage Fanclub gave the song a spin as a Songs from Northern Britain B-side. The solo has the simple innocence, ringing bends and circular feel of a beginner guitarist, endearing and full of soul.

[embedded content]

Grant Sharples, Contributor

Bloc Party: “Positive Tension” (Russell Lissack)

Silent Alarm has great performances across the board. You’ve got Matt Tong’s pummeling fills, Gordon Moakes’ ambling bass lines, Kele Okereke’s captivating voice, and Russell Lissack’s nimble guitar-playing. There aren’t many guitar solos on Bloc Party’s debut, but the ones that are here absolutely rip, especially the one on “Positive Tension.” After a steady buildup, which culminates in Okereke’s a cappella declaration of “so fucking useless,” Lissack tears into a 6/4 solo that marries adroit guitar work and a wave of fluttering noise whose alien source (what pedal/studio trickery is going on there?) I am unable to scavenge on the internet. “Play it cool, boy,” Okereke sings afterward, but Lissack already did.

[embedded content]

Rage Against the Machine: “Bulls on Parade” (Tom Morello)

How does Tom Morello make his guitar sound like that? In the famous “Bulls on Parade” solo, the Rage Against the Machine guitarist makes his instrument sound like a DJ scratching vinyl. In live footage, he almost looks like he’s bear-hugging it, messing with the pick-ups with one hand while scratching the upper frets with the other one. Throw some pedals in the mix, and you’ve got one of the most memorable guitar solos out there, one that displays Morello’s creativity and his talent for finding unconventional, imaginative ways to play a beloved instrument that no one else thought to do.

[embedded content]

Smashing Pumpkins: “Cherub Rock” (Billy Corgan)

Guitars have never sounded better than they do on Siamese Dream. On Smashing Pumpkins’ second album, Billy Corgan delivers sick riff after mind-melting solo after sick riff after mind-melting solo. It has a treasure trove of moments to choose from for this list, but one of its biggest standouts occurs in the opening track, “Cherub Rock,” in which Corgan executes a piercing solo that nearly breaches a frequency range only dogs can hear; there’s one note in particular that may as well be from the high E string on the 50th fret. He even takes the solo past the instrumental bridge, all the way up to the song’s final chorus, adding fills here and there in between the vocals. This is a record packed with sky-scraping solos, and it makes that clear from its very first one.

[embedded content]

The White Stripes: “Icky Thump” (Jack White)

First of all, there’s the riff, which feels like a solo in its own way. And then there are those white-hot solos (plural!). How does Jack White even do that>? It makes sense that Third Man Records now makes guitar pedals that replicate this bagpipe-esque shriek; it feels like a signature of his at this point. His mastery of the instrument is as show-stopping as the mystifying sounds he manages to elicit from it. It’s a Herculean task to point to just one segment of one solo, but there’s a point in the final solo where the guitar sounds like it’s asking “Hello? Hellloooooo?” Only Jack White could make a guitar talk. It’s a language he’s well-versed in.

[embedded content]

Matt Mitchell, Editor

Carly Simon: “You’re So Vain” (Jimmy Ryan)

“You’re So Vain” has been the subject of speculation and theories for 53 years. Everyone wants to know the true subject of Carly Simon’s diatribes. Some suspects have included David Bowie, David Cassidy, Cat Stevens, David Geffen, and James Taylor, among others. Simon’s husband Jim Hart said it’s not about a celebrity. Eventually, she confirmed that the second verse was about Warren Beatty. And, apparently, Taylor Swift knows who it is. Look, debunking drama and mystery is a fun game to play. But the older I get the less concerned I am with who or what Simon was singing about. These days, I get a lot of miles out of Mick Jagger’s uncredited backing vocals and Jimmy Ryan’s guitar solo. Ryan had been a member of the Critters but found his lane as a session musician. He played the “You’re So Vain” solo on a Gibson ES 335 and producer Richard Perry covered the licks in multi-tracking and reverb. It’s an uncomplicated solo, but Ryan’s vibrato is tasty. Radio-friendly soft rock was full of vibe-y guitars in the 1970s, but “You’re So Vain” has so much more bite than whatever flaccid, milquetoast chart strata was leaking out of John Denver. It’s a track with excellent body language and an even greater groove, thanks in some part to Jim Gordon’s thunderous tom fills and breathless snares. And when Ryan comes in with a whole new pocket, he bends the ax until it wails. Monstrous tones. As catchy as the day is long.

[embedded content]

Pescado Rabioso: “Cementerio Club” (Luis Alberto Spinetta)

Before the Argentinian group Pescado Rabioso disbanded, they released Artaud in October 1973. Bandleader Luis Alberto Spinetta’s previous music was complex, acoustic, and melodic. But with Black Amaya and Osvaldo Frascino involved, Spinetta’ work began to growl. He referred to his time in Pescado Rabioso as his “punk movement,” even though some of those licks he was playing were stone-cold blues scales. “Cementerio Club” has a nasty, nasty tone to it—blues and R&B fashion with harmonic jazz influence. For five minutes Spinetta bends his strings and lets the twine whine. That guitar of his talks in screaming paragraphs. I come back to “Cementerio Club” all the time, to hear Spinetta sing “How hot it will be without you in the summer!” and then walk on a humid, damn-near erotic wire.

[embedded content]

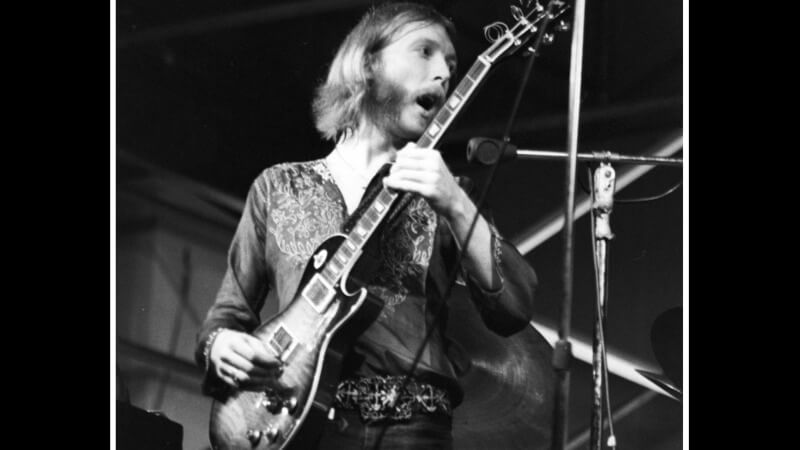

Thin Lizzy: “Cowboy Song” (Brian Robertson & Scott Gorham)

A song with not one, but two solos? Now that’s a vibe I’m willing to chase. “Powderfinger,” “Comfortably Numb,” “My Old School,” and “Marquee Moon” are a couple of favorites, but none of them stack up to Thin Lizzy’s took-in-Texas barnburner, “Cowboy Song.” The penultimate track on Jailbreak—and a scorcher on the album’s perfect side two, nestled ahead of the just-as-great “Emerald”—“Cowboy Song” is a true-blue ripper ascending from twin Gibson Les Pauls. I dig a Dubliner like Phil Lynott singing about Western daydreams and American wanderings. But what I dig even more is that co-harmony lead from Brian Robertson and Scott Gorham. Their guitars streak through tones I still can’t wrap my head around. Like, those bends scream. No effects, reverb, or delay. Just two Irishmen knocking my block off every time. The solo that comes once Lynott yells out, “Here I go!”? It packs a wallop.

[embedded content]

WAR: “Slippin’ into Darkness” (Howard Scott)

A year before dropping their masterpiece The World is a Ghetto, WAR was still figuring out its post-Eric Burdon identity. In November 1971, the Long Beach ensemble shared All Day Music, a great record bolstered by one of its singles: “Slippin’ into Darkness.” The track builds through African and Latin rhythms and the pocket via a slow, humid groove. Howard Scott’s guitar is a part of the design but never above it. That’s the beauty of WAR: every band member is in lockstep with each other. The chemistry is off the charts, and the telepathy is obvious. Scott’s solo near the end doesn’t roar. It’s as complimentary as they come, sometimes becoming interwoven with the horns and percussion around him. I’d say it takes some serious craft to pull out a lick like that but never put it under lights. Finesse ≠ flashy. Scott makes some dirty cursive out of those bends.

[embedded content]

Sam Rosenberg, Contributor

Radiohead: “Paranoid Android” (Jonny Greenwood)

The prescient second track off Radiohead’s 1997 magnum opus OK Computer is built into four distinct, robustly orchestrated sections, each one dedicated to a particular mood regarding the increasingly antisocial behavior dictating modern culture during the late ‘90s. Jonny Greenwood’s sinister guitar thrums through each part, snaking itself around Thom Yorke’s seething snarls before leaning hard into a distortion-heavy, venom-laced solo. Its presence is vital in not just in acting as a powerful gateway into “Paranoid Android”‘s chilling, downbeat third segment, but also for being a stirring sonic articulation of Yorke’s angst around the ways in which we dehumanize one another, whether through violence, incuriosity, or both.

[embedded content]

The National: “The System Only Dreams in Total Darkness” (Aaron Dessner)

The National aren’t really known for guitar solos. Their music either remains at a hushed, gentle frequency or rouses into a loud gallop, but even in the latter case, the band seems to prefer more intricate arrangements over traditional, radio-friendly ones. However, one of the few instances in which they have used a guitar solo—on “The System Only Dreams in Total Darkness,” the awesome lead single from their 2017 record Sleep Well Beast—turned out to be an incredibly brilliant one. As lead singer Matt Berninger laments our culture’s growing demise, Aaron Dessner’s guitar spasms like an old car engine struggling to start until finally roaring to life. Buoyed by some heavenly backing vocals and vigorous drum fills, the solo is positively rapturous, a shout into the void that’ll bowl you over with its fury and urgency as much as galvanize you to keep going despite it all.

[embedded content]